Change the mood and spice up your tunes with parallel major and minor keys

Impart a touch of sadness or melancholy to an otherwise happy and predictable-sounding progression

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this lesson, I’d like to begin discussing an intriguing type of chord change that many composers have put to great use in countless major-key songs. It involves borrowing a chord from what’s called the parallel minor key to create a temporary harmonic detour and a surprise shift in musical color and mood that’s often used to impart a touch of sadness or melancholy to an otherwise happy and predictable-sounding progression.

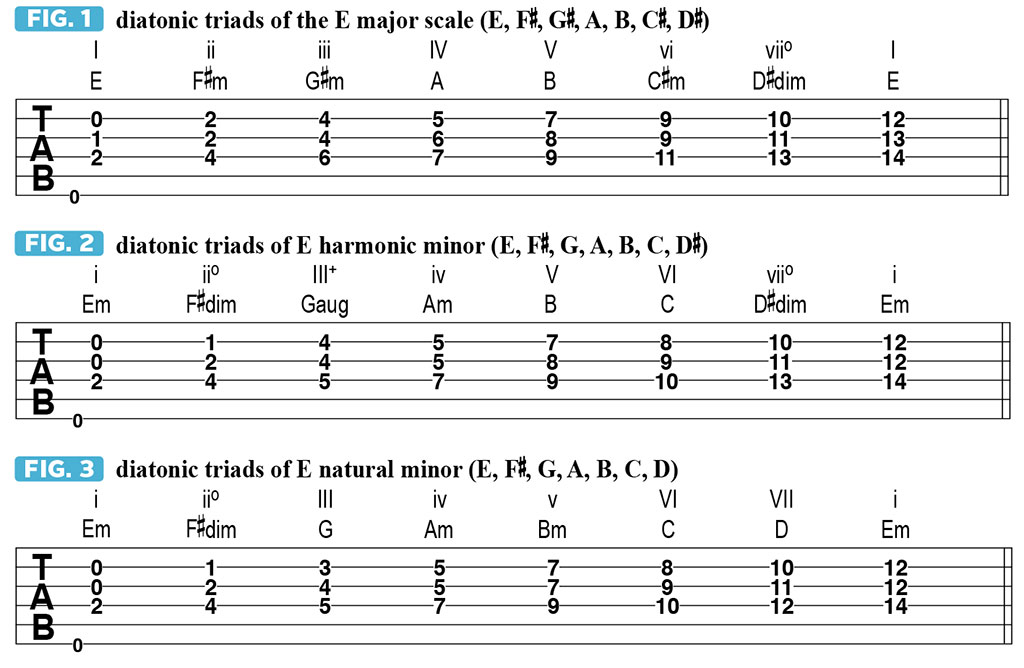

Let’s start with a theory primer. In any major key, you have a set of what are called diatonic triads, which are three-note chords based on the seven notes, or degrees, of that key’s major scale. Using the key of E to illustrate, FIGURE 1 depicts the triads generated by the E major scale, which is spelled E, F#, G#, A, B, C#, D#.

The first, fourth and fifth chords - E, A and B - are built from those named scale degrees and are all major, as indicated by the uppercase Roman numerals I, IV and V. The second, third and sixth chords - F#m, G#m and C#m - are built from those scale degrees and are all minor, as denoted by the lowercase Roman numerals ii, iii and vi. The seventh and final chord, D#dim, is a diminished triad, indicated by the analytical symbol vii°. (A lowercase Roman numeral followed by a superscript circle, or degree symbol, signifies diminished).

E major’s parallel minor key is E minor, as opposed to its relative minor key, which would be C# minor. FIGURE 2 presents a set of diatonic triads built from the parallel E harmonic minor scale (E, F#, G, A, B, C, D#), for which the third and sixth degrees of the major scale are lowered, or flatted - b3 and b6 - in this case giving us the notes G and C.

Notice that the third triad generated from this scale is augmented, Gaug (G, B, D#), which is a chord type whose various applications we recently explored in depth in the previous four lessons. This chord is analyzed with the symbol III+. (A superscript plus sign after an uppercase Roman numeral or chord letter name signifies augmented.)

Now, you could also use the parallel E natural minor scale (E, F#, G, A, B, C, D), also known as E pure minor and the E Aeolian mode, to generate a similar but slightly different set of diatonic triads, as illustrated in FIGURE 3. This scale is like harmonic minor but has a lowered, or flatted, seventh degree, D, which gives us a minor v (five) chord, Bm (spelled B, D, F#), and a bVII (flat seven) major triad, D (D, F#, A), which is rooted a whole step below the keynote E, as opposed to a half step (D#), which is the case with both E major and E harmonic minor.

It’s important to note here that E natural minor’s three major chords - III, VI and VII (three, six and seven), G, C and D, respectively - all have flatted root notes that differ from their counterparts in E major, namely, G instead of G#, C instead of C# and D instead of D#, which is understood in the context of natural minor. But if we’re thinking in the key of E major and referring to the chords G, C and D, they would be properly acknowledged as bIII, bVI and bVII.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

This specification is necessary because if you were to just say 'three major,' 'six major' or 'seven major' in reference to the key of E major, you would actually be referring to the major chords G#, C# and D#, which are alien to both E major and E minor.

An interesting thing about applied harmony, meaning chords that composers and songwriters actually use in the real world, is that, in a piece that’s in minor key, for example, you’ll often find the III major and/or VII major chords from natural minor, but also the V major (or dominant 7), which is from harmonic minor.

Using the key of E minor again to exemplify, that would be the chords G (G, B, D), D (D F# A) and B (B, D#, F#), even though they don’t all live within the same scale. This is an example of a concept and practice known as modal interchange, or modal mixture, which we will explore further next time and beyond, in regard to parallel major and minor keys, illustrated with plenty of good, interesting examples from famous songs.

Senior Music Editor 'Downtown' Jimmy Brown is an experienced, working musician, performer and private teacher in the greater NYC area whose professional mission is to entertain, enlighten and inspire people with his guitar playing.

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.