“There is a lot of fun to be had by putting random alternative bass notes under a chord”: Pete Townshend, Ray Davies and David Bowie all used third inversion chords – here’s why (and how) you should, too

If the idea of third inversions seems all upside down, fear not: these five examples show how easy they are to put together – and how musical they are when you apply them in a song

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Previously, we’ve looked at what happens when you swap around the notes in a triad and put the 3rd at the bottom (first inversion), or the 5th at the bottom (second inversion). In this next instalment, we’ll look at third inversion chords.

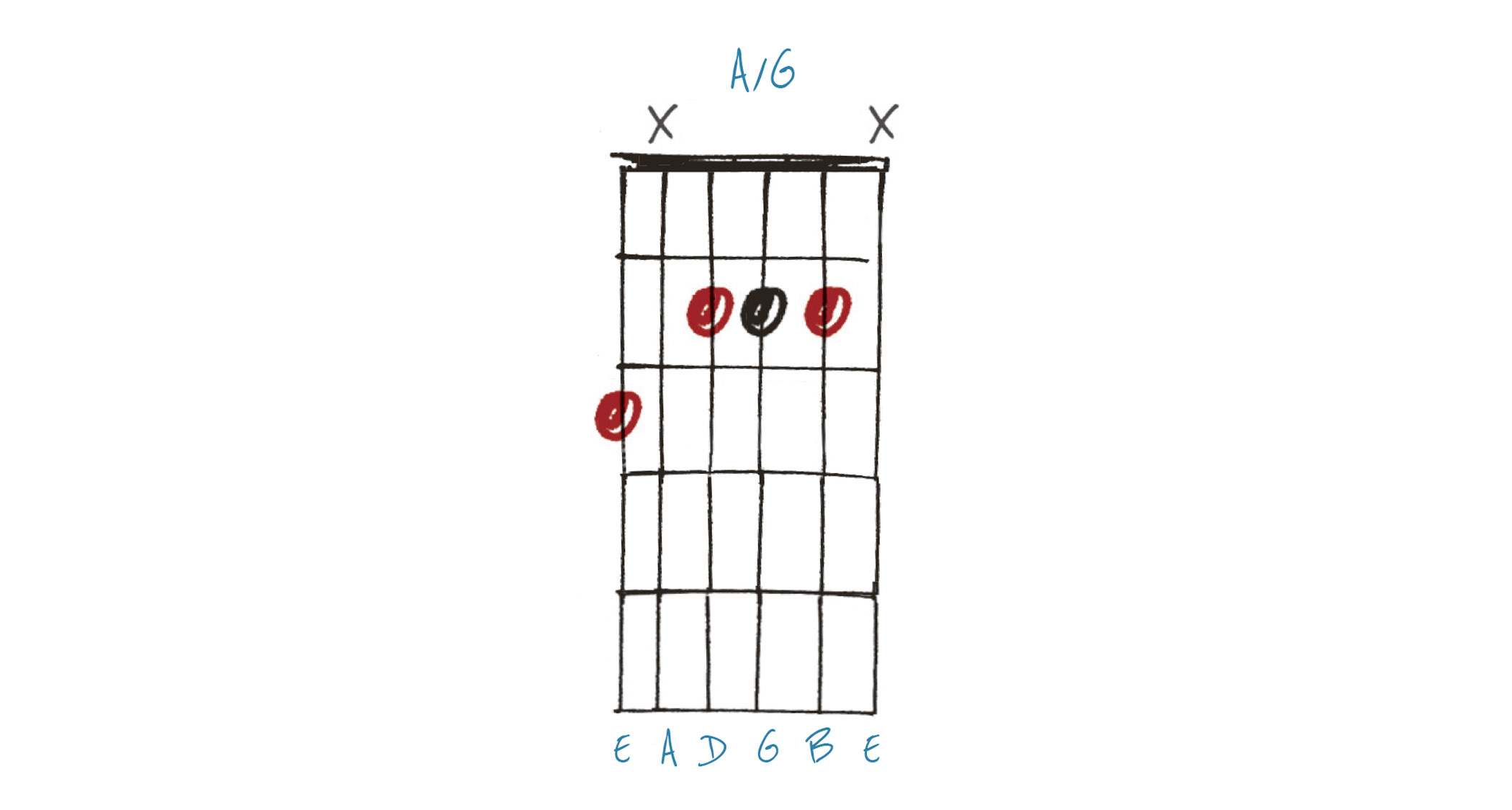

To create these, we add a dominant (aka flat) 7th to a triad/chord and move that to the bottom. In practice, these are generally notated as slash chords. For example, in an A/G chord (see Example 1), the b7 (G) is moved to the bottom.

Like suspended chords, this definitely feels like its leading somewhere – try following up with a D/F# (D first inversion) and you’ll recognise a very popular chord move, heard across multiple genres.

Slash chords are a convenient way to notate the various inversions, but with chords it’s always good to know the ‘whys and wherefores’. Having said that, there is a lot of fun to be had by putting random alternative bass notes under a chord! Hope you enjoy and see you next time.

Example 1. A/G

This A (third inversion) is given the more modern name of A/G, but knowing the traditional chord theory highlights that the reason it sounds the way it does is the dominant 7th at the bottom.

This is a movable shape, though care needs to be taken with muting the unwanted strings.

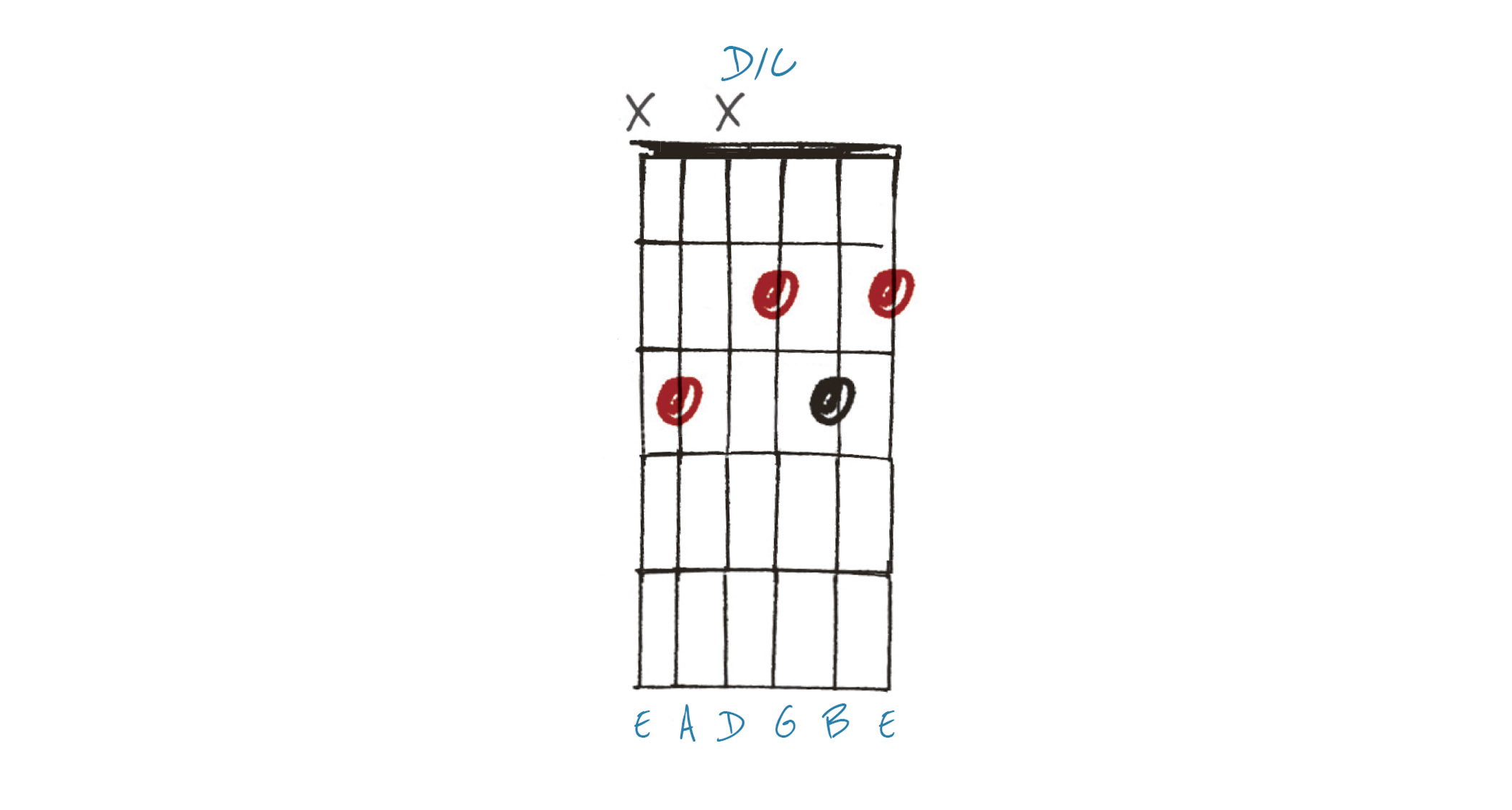

Example 2. D/C

This D/C (D third inversion) is another movable shape requiring careful muting. You can really hear that it wants to lead us somewhere; perhaps G/B (G first inversion) would be a good place.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

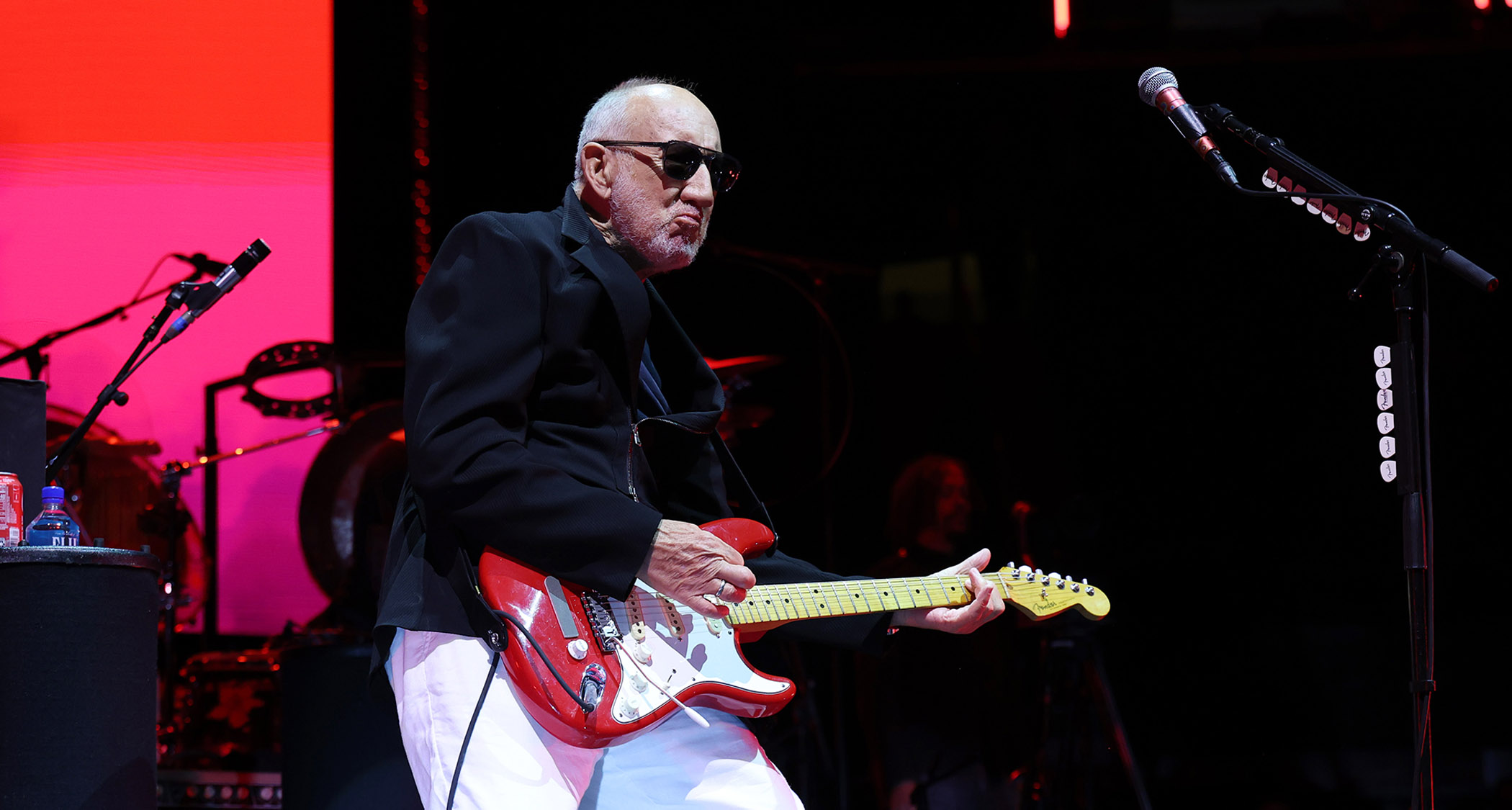

You can hear Pete Townshend experimenting with third inversions at the beginning of The Who’s See Me, Feel Me.

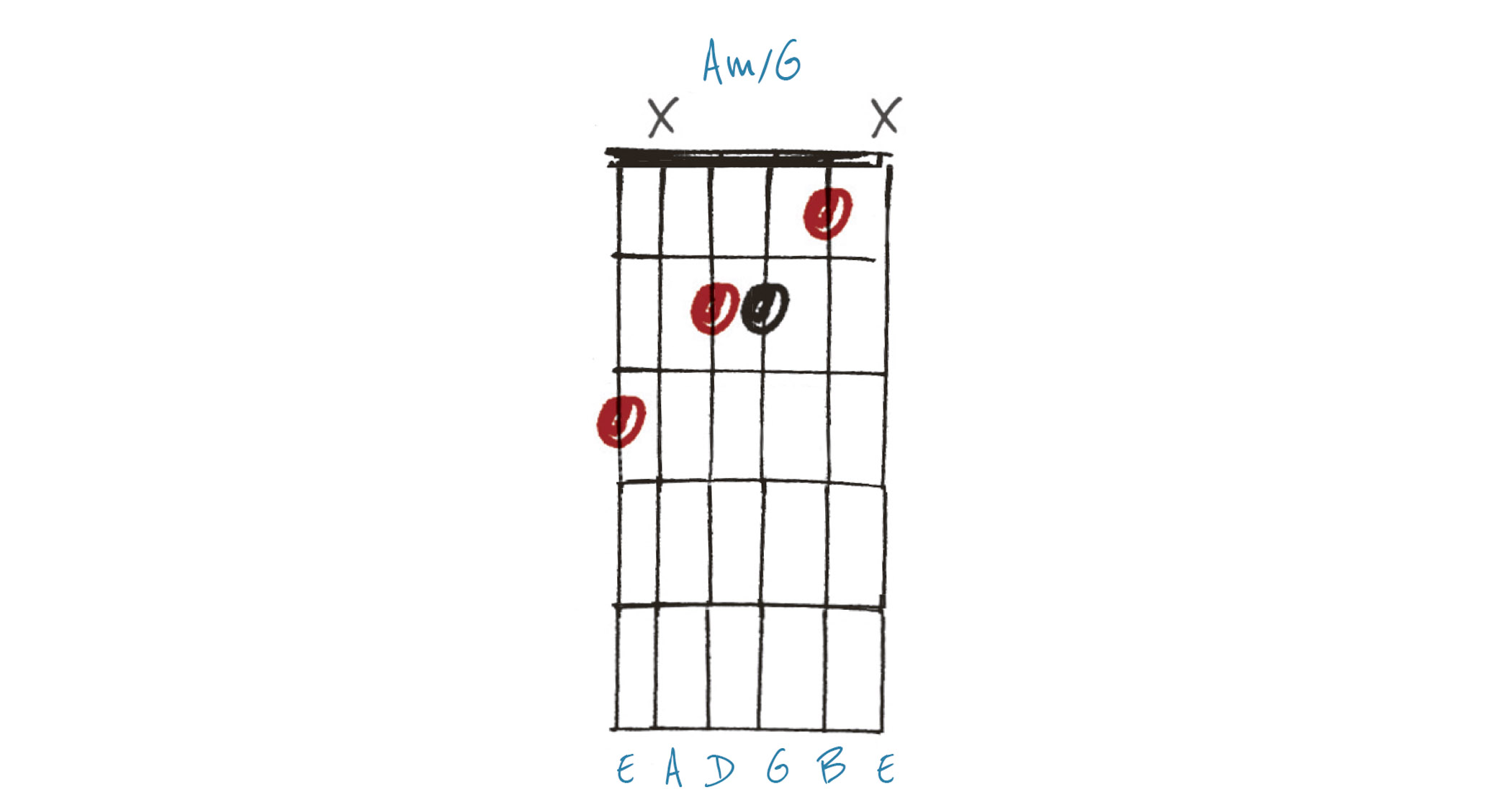

Example 3. Am/G

This Am/G demonstrates that this approach doesn’t only apply to major chords. Here, the b7 (G) is moved to the bottom, giving the feeling it should be leading somewhere.

For a good example of this in the wild, check out the chorus of David Bowie’s Starman, where it leads to C major.

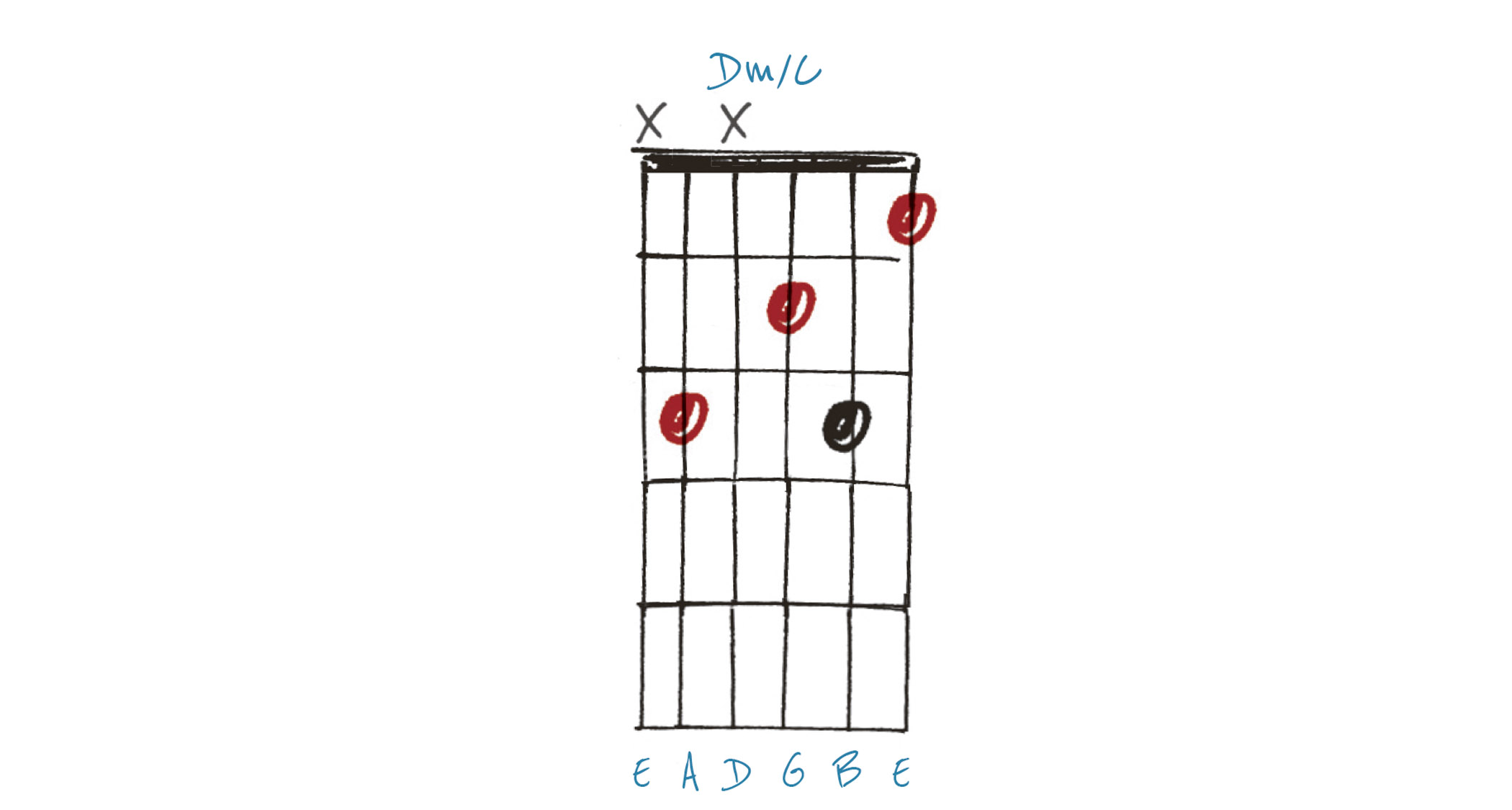

Example 4. Dm/C

Here’s another movable minor third inversion shape, in this case Dm/C.

Now you know about these chords, you’ll start hearing them everywhere – for instance, as a key part of the descending progression in The Kinks’ Sunny Afternoon, Holiday by The Scorpions and Dear Diary by The Moody Blues, among many others.

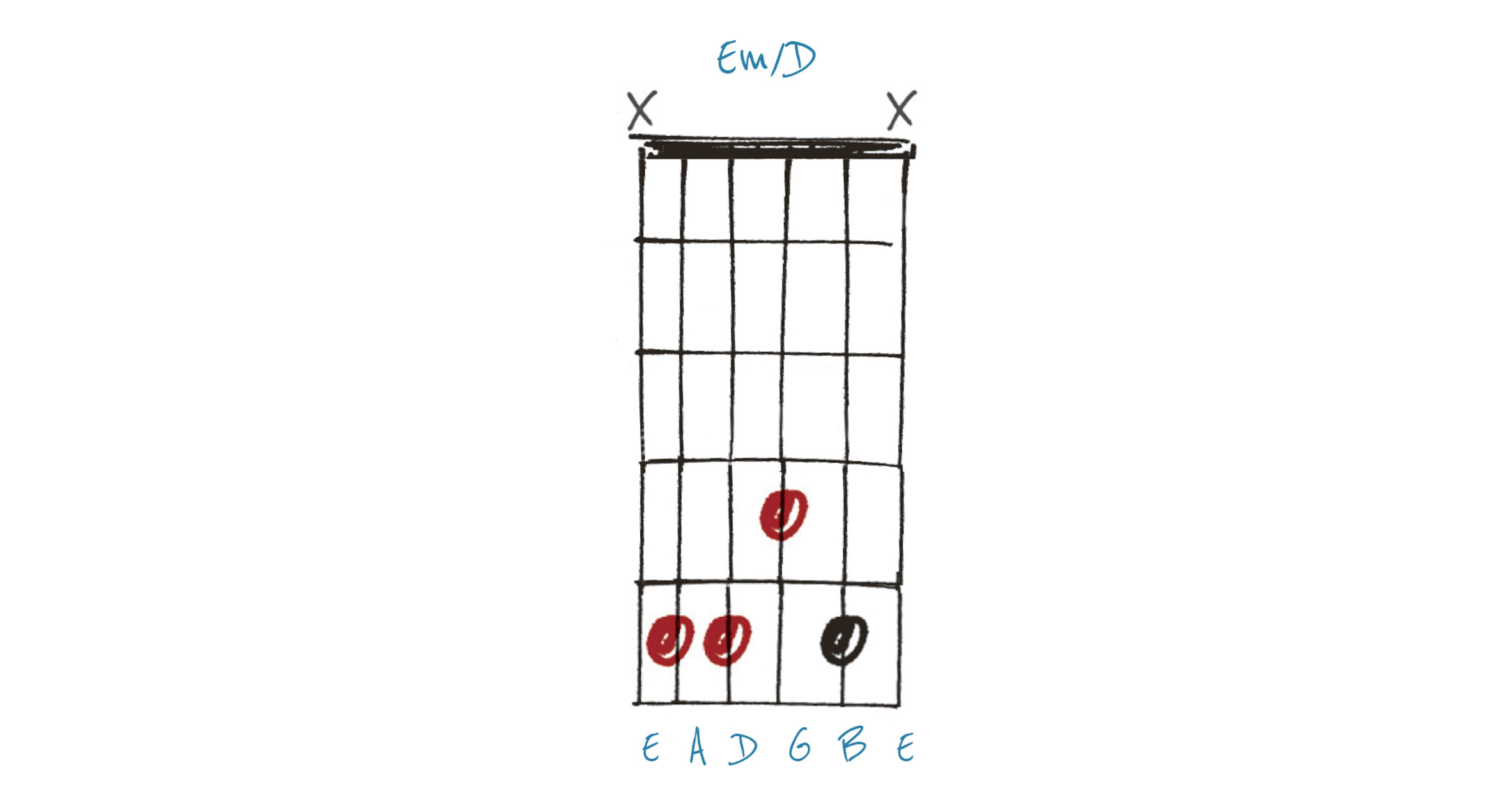

Example 5. Em/D

This Em/D sounds like something Nick Drake might have used, albeit in a non-standard tuning.

Like Example 4, see if you can find/create examples of a descending pattern in the bass. This can be done under a static chord (fingers permitting) or by combining other chords/inversions.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.