David Gilmour is a master of melodic bluesy phrasing – here are 3 ways to cop his style in your own playing

Whether you call these solo ideas minor blues or embellished pentatonic/blues scale, the effect is the same, freeing you up from established patterns to hold your audience's attention

Learning scales and patterns is perhaps one of the less exciting aspects of guitar playing – and, arguably, many of our heroes didn’t approach their playing in this way, either.

However, consider the process of writing and recording material, and rehearsing then touring, which obviously involves playing those same tunes night after night. This in itself can teach us so much about what works and what doesn’t, simply through an intense process of trial and error.

If the old adage about one gig being worth a dozen rehearsals holds true, what are the benefits of a long tour? It’s true to say that many professional musicians (myself included) come off tour able to play the set blindfolded, but feeling a bit rusty on anything else… However, this is temporary and the longterm gains are clear. But where does this leave everyone else?

It’s possible to transform your playing without repeatedly going through the album/tour cycle, but it does take discipline to play and practise every single day and perhaps record yourself (in private – studio quality is not necessary!) then listen back with as objective an ear as possible. Yes, we are often our own harshest critics, but you can make this work for you by taking notes and deciding on positive steps to improve in any weak areas.

This brings us neatly back to the idea of learning scales and patterns, with the emphasis on the latter. A slow minor blues like the example solo gives us plenty of time to think about note choice and phrasing. Some of the ideas in the examples are derived from chord tones or chord extensions.

But, if you prefer, they could also be regarded as embellished pentatonic/blues scale licks. Play these, or similar ideas, often enough and they will become part of your vocabulary. Hope you enjoy and see you next time!

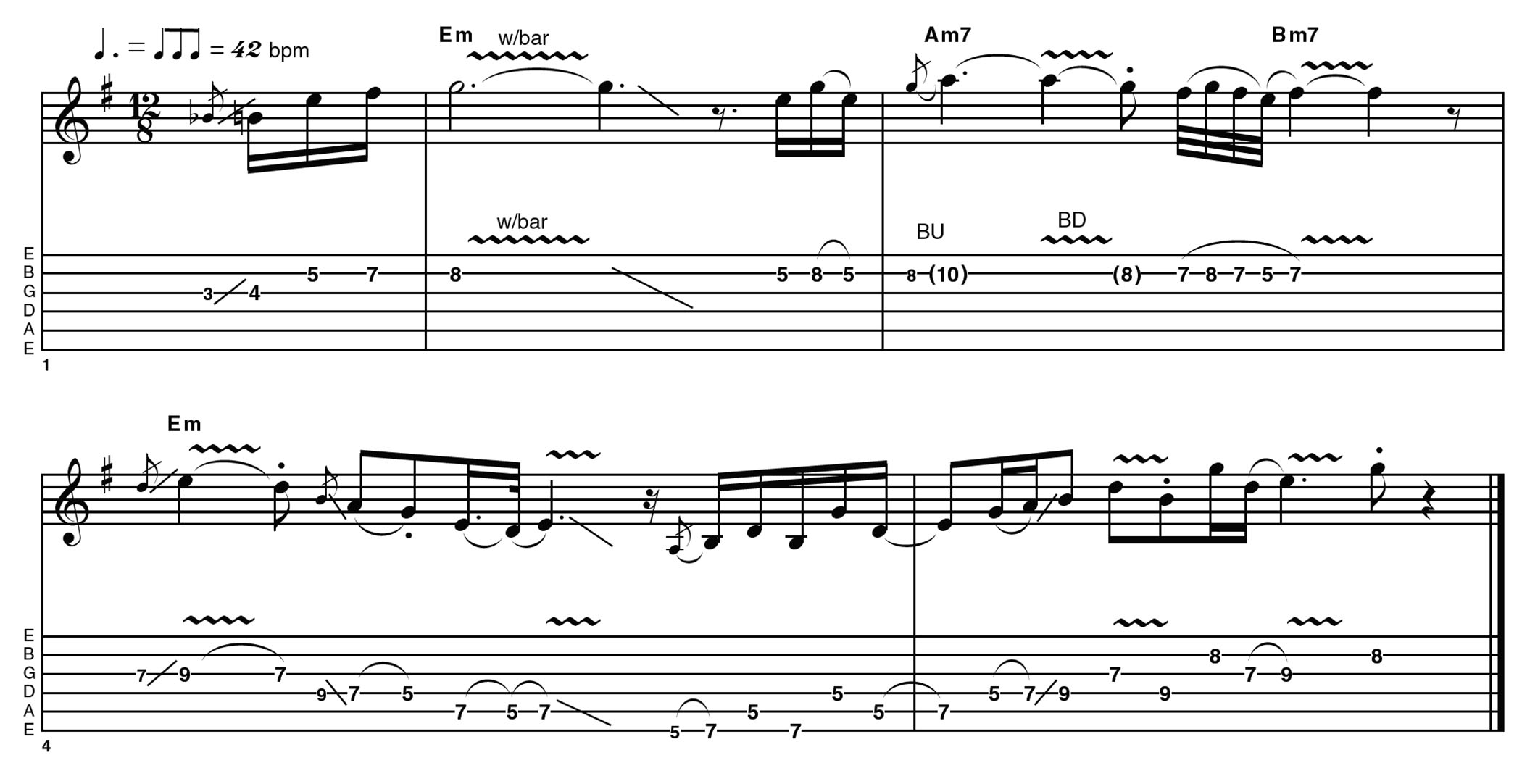

Example 1

In the pickup to this first phrase, I’m spelling out part of an E minor scale, though you could also say it’s an E minor triad (G B E) with an F# added before the G on beat 1 of bar 1. This gives us more detail than sticking solely to the pentatonic scale.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The change to A minor then B minor in bar 2 is followed with an ear for their respective triads (A C E and B D F#) but without needing to change position on the fretboard.

Oddly enough, the last two bars feature more movement between positions over a static chord, playing a similar idea over two octaves using the E minor pentatonic scale.

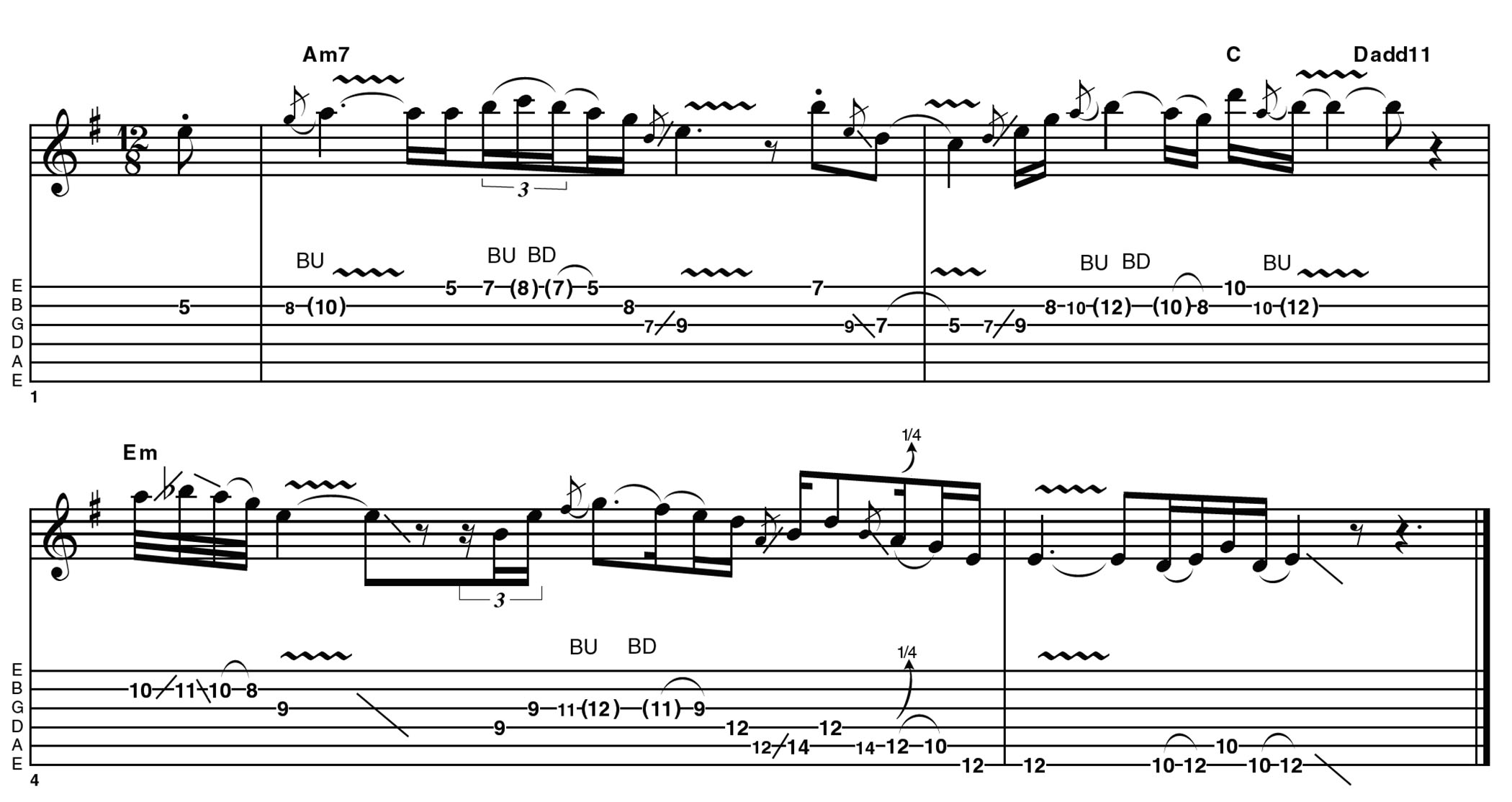

Example 2

Shifting to A minor, this second phrase targets the 9th (B) in what would otherwise be a regular minor pentatonic phrase, albeit sliding between shapes 1 and 2.

The brief excursions to C and D don’t really ask anything too specific of us in terms of note choice, though perhaps it is worth experimenting with C and D triads? The next main chord is E minor.

Nothing too fancy going on here, but there is a bend from F# to G in bar 3, emphasising the 9th in the key of E minor. Watch out for sneaky staccato notes!

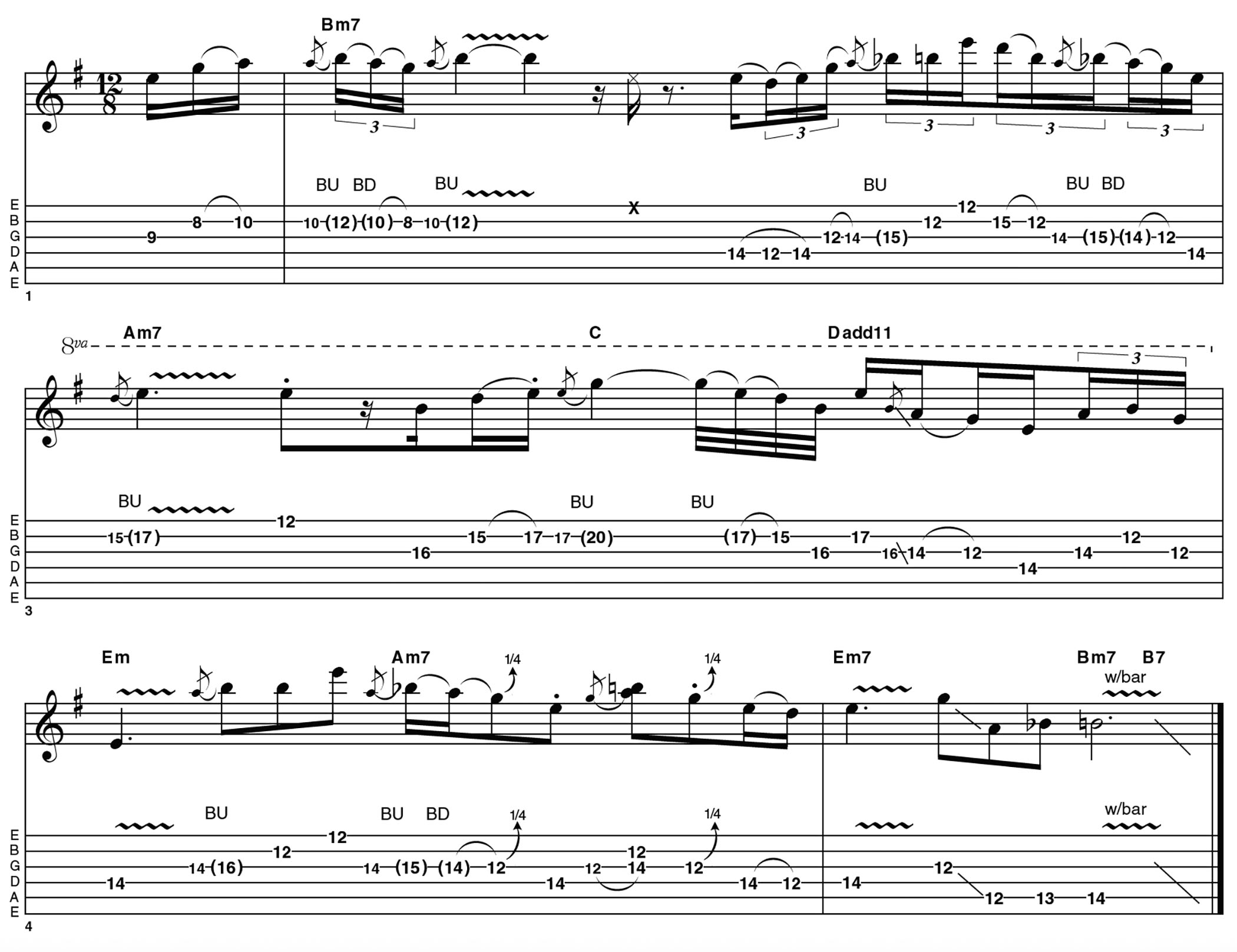

Example 3

Switching to the bridge pickup for dramatic effect, this final example is perhaps the most obviously pentatonic, switching between shapes 4, 1 and 2. Somehow, the unembellished pentatonic sounds ‘tougher’ for this rise in dynamic…

That’s where we stay, being pretty and melodic sidelined in favour of a few more flourishes, before a short chromatic run up to B at the end. We don’t always need to spell out each chord, but it’s good to know what’s going on harmonically so we can pick and choose.

Allow yourself a bit of leeway for timing; this is transcribed as faithfully as possible but need not be set in stone.

Hear it here

John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers – A Hard Road

After Eric Clapton had recorded the infamous ‘Beano’ album and moved on to form Cream, there was a vacancy to fill. Enter Peter Green. On this 1967 release, he shows himself very able to channel the spirit of Clapton on tracks such as The Stumble and Another Kinda Love.

However, on The Super-Natural we really hear him coming into his own, having a profound influence on Carlos Santana, Gary Moore and many others in the process.

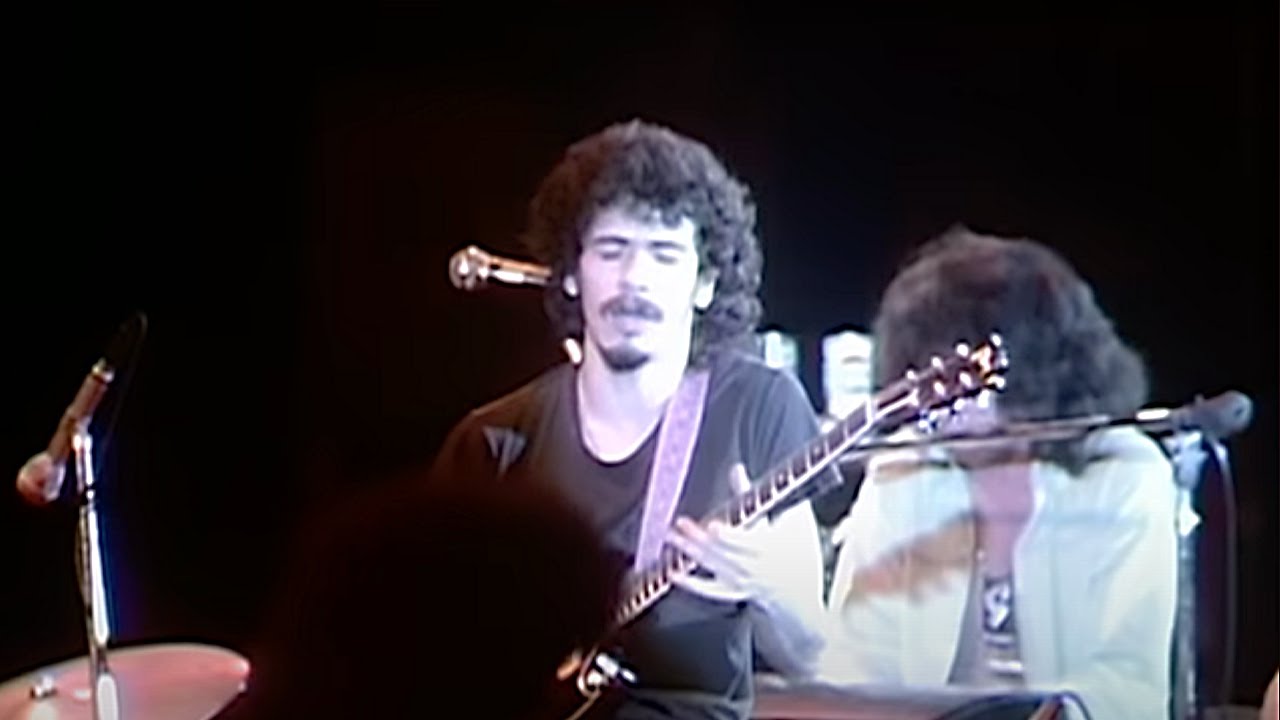

Santana – Abraxas

Released in 1969, this second album from the band features a cover of Peter Green’s Black Magic Woman, alongside the well-known tracks Samba Pa Ti and Oye Cómo Va.

In fact, we could probably have cited any of Santana’s albums here, as his distinctive playing remains the centrepiece of his music, combining American and Mexican influences, while frequently using pentatonic lines but just as often adding melody via chord tones, arpeggios and long held notes.

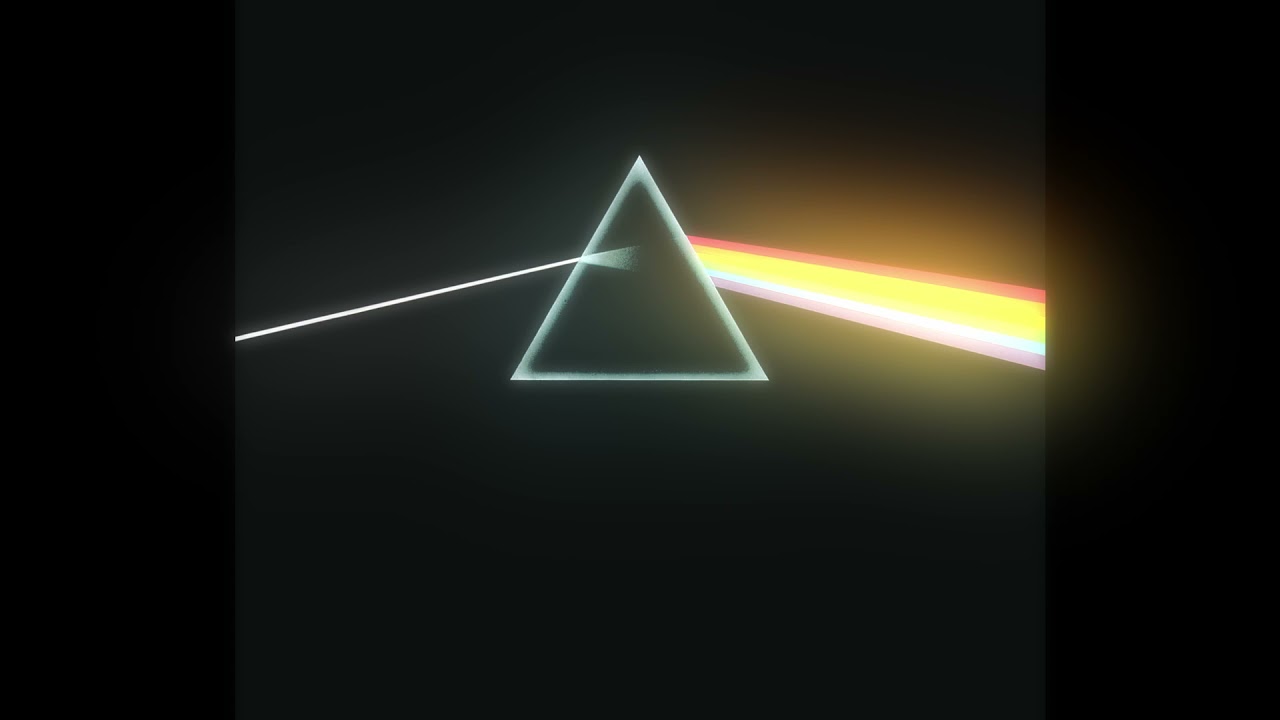

Pink Floyd – The Dark Side Of The Moon

David Gilmour is a very obvious name to put out there when thinking of melodic-blues-influenced players. Like Santana, you could approach any of the Pink Floyd or later solo material and find lots of examples.

Of particular interest here, though, is how he fits his blues-based style into tracks such as Time and Any Colour You Like where he trades licks against himself in stereo. Money contains some more obviously bluesy licks, though still with lots of memorable melodic lines.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.