Doug Aldrich Master Class: 10 Steps to Monster Chops, Part II

Guitarist extraordinaire Doug Aldrich offers a slew of exciting and inspiring licks and technical exercises to help you become the player you aspire to be.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

HIGHER STANDARDS

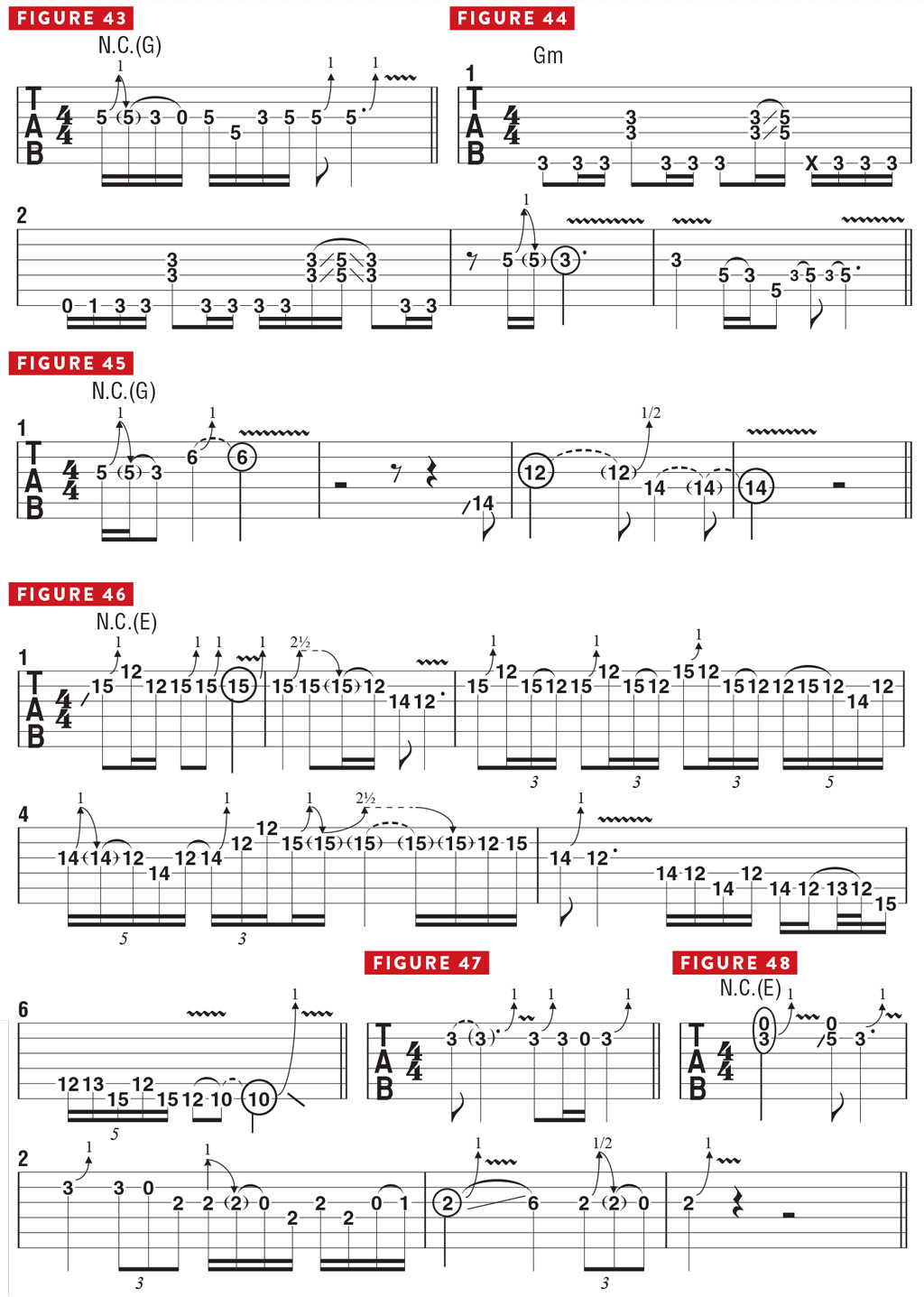

Randy Rhoads, Eddie Van Halen and Ritchie Blackmore were more schooled than the “standard” rock and blues players; they were using more exotic notes in their solos—more of those “in-between” notes. Ritchie was playing some different things, like melodic ideas based on the harmonic minor scale and the Phrygian mode. For me, that’s where learning about the modes came into play.

THE MIXOLYDIAN MODE

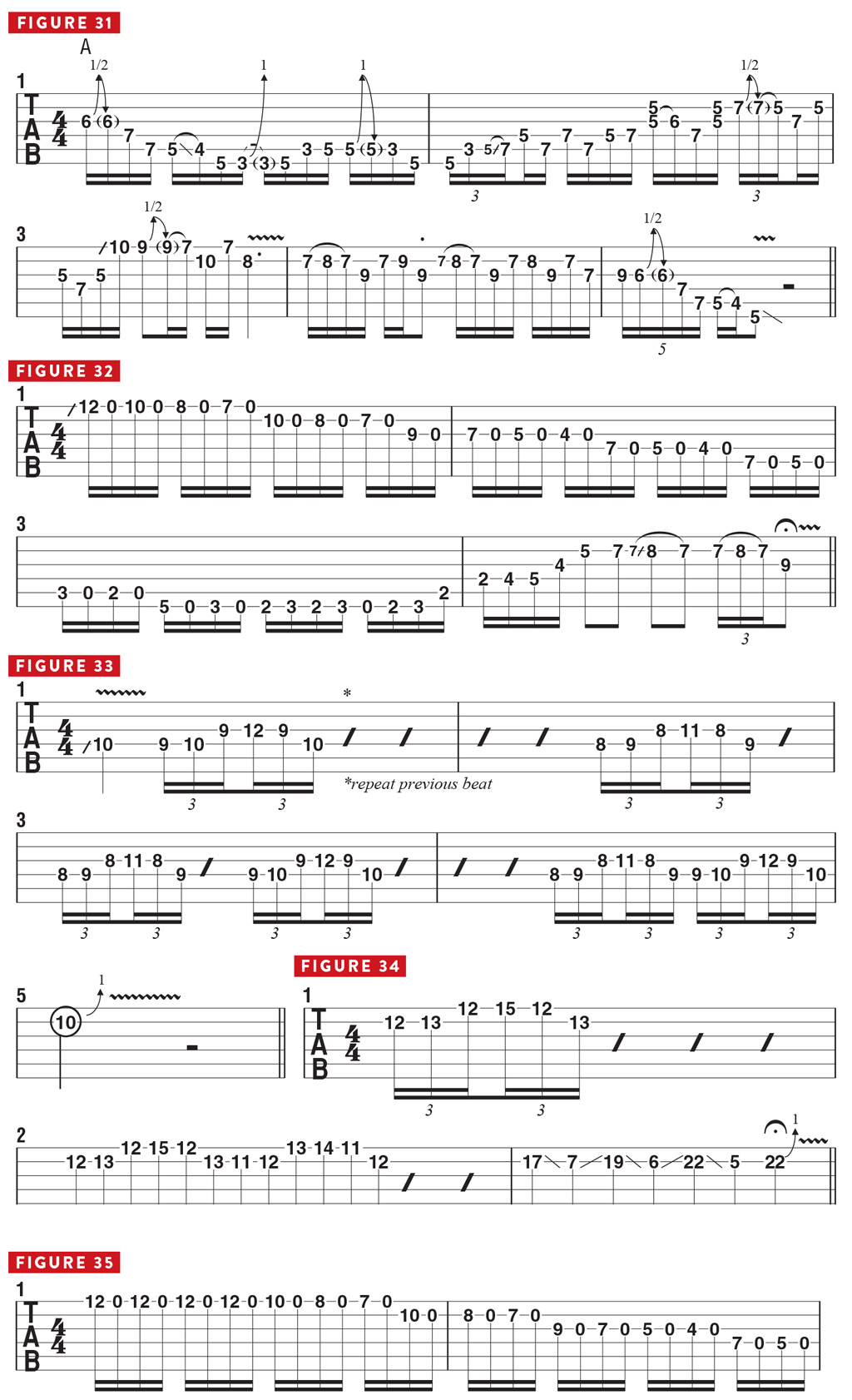

I’ve always loved Michael Schenker’s playing and I discovered, at one point, that he would use the Mixolydian mode in many of his solos. He would play runs that were kind of half major and half minor, like this (FIGURE 31) — mixing things up and bringing the major third in and out of his lines.

Another guitar player I really love is Gary Moore, and I soon discovered that he had been a big influence on Randy Rhoads, who I was aware of first. My introduction to Gary was his 1984 album Corridors of Power, which is just an amazing record!

Gary loved to play really fast staccato (short, punctuated) pull-off licks, like this phrase (FIGURE 32), which is based primarily on the E natural minor scale — also known as the E Aeolian mode (E F# G A B C D). Another hallmark of Gary’s lead style is the use of fast symmetrical sequences, such as this one (FIGURE 33), which is based on E harmonic minor (E F# G A B C D#) and can also be moved up one octave, like this (FIGURE 34). Gary had that signature intensity in his attack in everything he played.

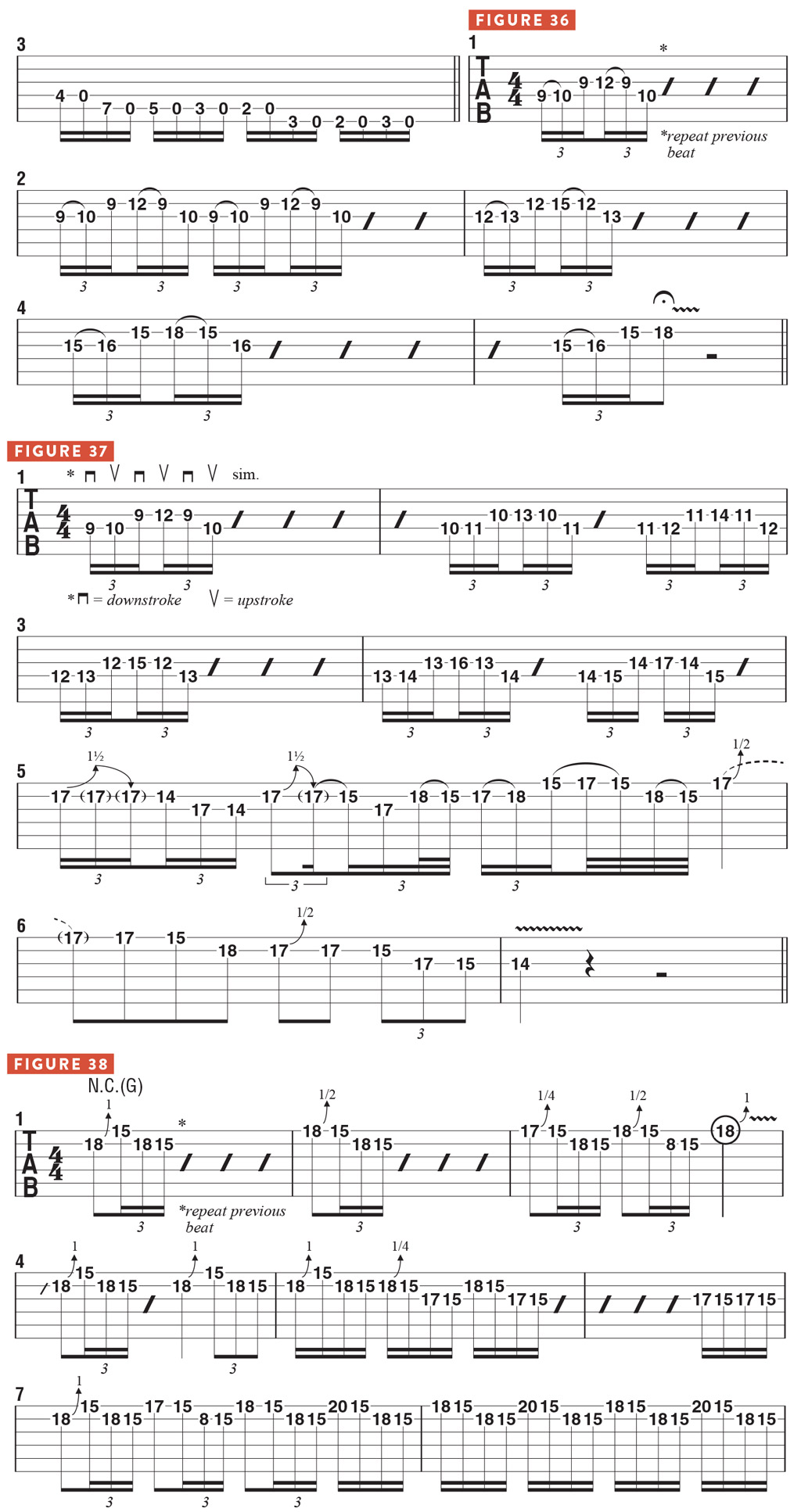

The first lick (FIGURE 32) is great to use as a “connection” builder for steady staccato picking (FIGURE 35): I start with a downstroke and then use alternate picking (down-up-down-up) to pick every note in the phrase. The second lick (FIGURE 33) is good to articulate as an all-picked staccato phrase, but it also works well played legato (smoothly flowing and connected), with some hammer-ons and pull-offs (FIGURE 36). The “shape” is symmetrical and can be easily moved to other pairs of strings, and areas of the fretboard. For the staccato version (FIGURE 37), it’s good to start slow and then build up speed, keeping your pick-hand wrist loose and relaxed throughout.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

STACCATO PICKING

Here’s another great way to practice and develop your staccato picking — this time working with the top two strings in the key of G minor (FIGURE 38). I know that a lot of players out there already know some of these licks, but the idea is to concentrate on getting the picking and fretting hands working together in tight synchronization. As you play through these examples, notice that the index finger stays rooted at the 15th fret, barred across the top two strings, while the other fingers alternate in various sequences. Many of these melodic “shapes” are repeating four-note patterns — and combining them with some index-finger bends takes us back into Jeff Beck territory (FIGURE 39).

BOX POSITIONS

Some players like to have a lot to think about while they play, but many rock players will get a lot out of working on these two-string “box position”-type repeating patterns — which is something Randy Rhoads did all of the time in his solos and his live solo guitar spotlight.

Mixing staccato and legato phrasing approaches, within the standard minor pentatonic box, reflects the general approach all rock and blues players use most often (FIGURE 40). In this example, I begin on the top two strings but then, quite naturally, move down to include the G and D strings. It’s very useful to visualize the fretboard, in terms of small box areas, with licks that remain on pairs of adjacent strings.

This lick is built from that approach (FIGURE 41), but each melodic shape is derived from 1-3-5 (root-third-fifth) arpeggios that reference different chords, within the key of G major. With this type of lick, I always need to start off slowly, until I get it sounding really solid, before increasing the speed and intensity.

SIMPLE VERSUS COMPLEX

I think it’s good to strike a balance between simple and complex licks and ideas — and keeping it simple is a good, solid approach to take, a lot of the time. Having said that, I know there are a lot of players out there that need to be pushed beyond that, to keep their interest and inspiration up. I try not to analyze my playing too much; the prime objective for me is to express as much feeling and emotion as possible, and I don’t want any thought processes to get in the way of that.

For those looking to expand their musical knowledge as much as possible, taking the opportunity to go to a music college is a great idea, and will prove to be invaluable. I know many players that went to Berklee, GIT, and other electric guitar-friendly music colleges, where they had the opportunity to acquire so many useful musical skills — such as being able to fluently sight-read and write musical charts for guitar, as well as other instruments. It’s such a great skill to be able to listen to a song once and be able to hear all of the changes and transcribe a chart, without even needing to pick up a guitar!

Equally important is the other side of it: you have to experience the down and dirty techniques essential to rock guitar, and be sure to not lose focus of the value of that too!

VIBRATO

A perfect example of what I’m talking about here is finger vibrato; I know players that are incredibly skilled with brilliant technique, but unless they make a mistake or hit a crazy vibrato, their playing doesn’t “speak” to me at all.

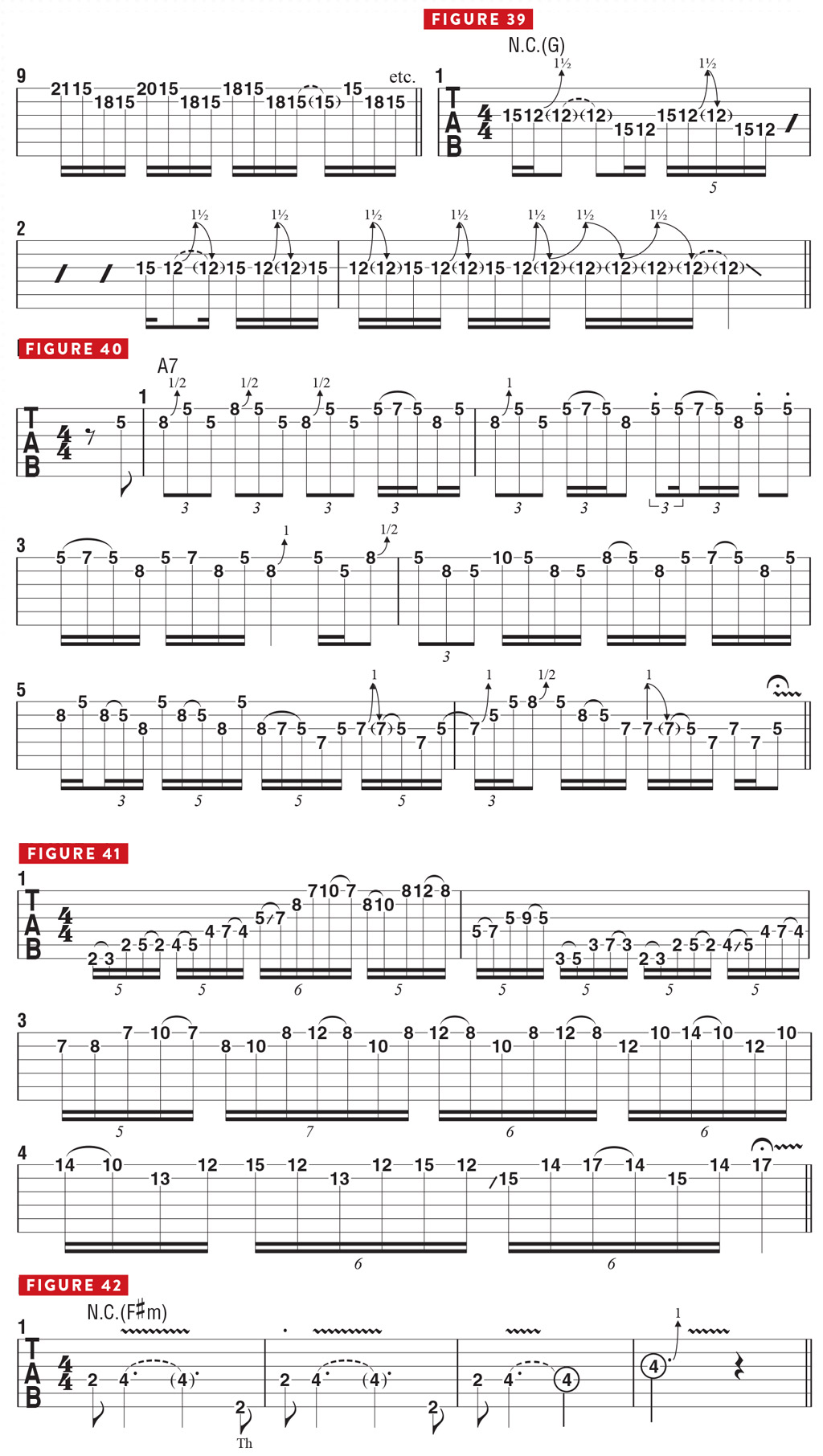

There are no rules when it comes to vibrato; there are so many different ways to apply vibrato to a note. The first one to look at is the Ritchie Blackmore-style vibrato (FIGURE 42), which is a fast, short note shake that can be performed either by turning the wrist or moving the guitar itself — or a combination of the two. I like a vibrato that’s a little slower and wider, like this (FIGURE 43), which is not super wide.

The vibrato one chooses should fit the feeling of the song. If you’re playing over a very aggressive groove, like this (FIGURE 44), a really slow, wide vibrato might not work best; I think a tighter, faster vibrato will better serve the vibe of the music. Something Randy and Stevie Ray Vaughan had in common was to shake the entire guitar when performing big, aggressive-sounding vibratos. When a player like John Sykes used a very slow and wide vibrato, that became a signature of his sound.

There is no “best” vibrato — it’s more about personality, and finding the right vibrato to suit your musical intention. Performing vibrato on guitar is very much like singing — most singers will hit the note first, wait at least half a second and then add the vibrato, once the note is sustaining and the target pitch is established — and guitar players will benefit from utilizing this same approach when adding vibrato to a note at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of a phrase.

STRING BENDING

The way in which one bends a string is a huge part of the “feel” of a musical statement. In this lick (FIGURE 46), I move the bends to virtually every string, pausing on a given note, during the phrase, to bend the string anywhere from a half step to two whole steps.

When bending strings, there’s nothing worse than going a little sharp or a little flat of the target pitch. The idea is to practice bending with confidence, so that you will get to the note you want to hear that’s also the correct note for the scale or chord. A good way to practice bending technique is to start in the key of E, bending the D note on the B string’s third fret up one whole step to E (FIGURE 47). You can compare the sound of the note you’re trying to bend up to by first playing it as a normal, unbent note — then bend up to that same pitch from a whole step below. A good exercise is to bend from D to E on the B string while also sounding the open high E string; this way, you can hear if the bend’s pitch is correct. If you bend too far, or not enough, you will hear that it is not the sound you want to produce — due to a fast, pulsating sound, like when you’re tuning one string to another by ear. You want all of your bends to sound true and intonated properly (FIGURE 48).

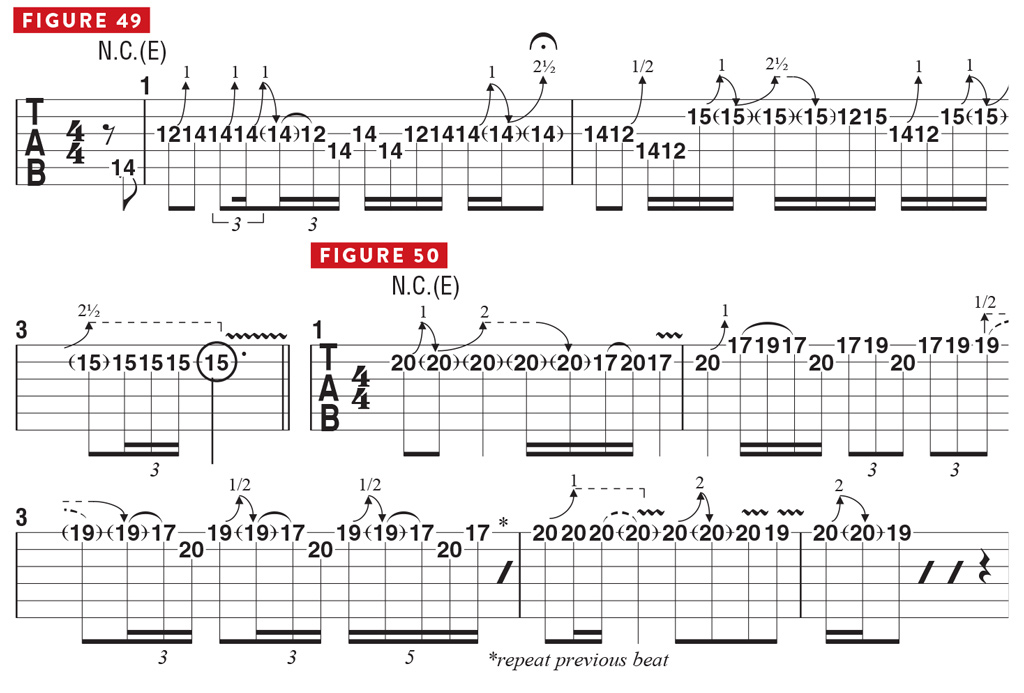

I really like over-bends, wherein one bends the string more than the standard whole step to one and a half, two, or two and a half steps (FIGURE 49). It lends an air of unpredictability while also sounding really aggressive. When practicing bends, I like to try to challenge myself to devise the most difficult string bends I can (FIGURE 50). It’s also really helpful to use two or three fingers to push the string and hook your thumb over the top side of the fretboard.

GIMMICKS

Let me say this: you can always shred. You can always play with a lot of emotion, doing your very best to tear someone’s heart out with a lick of your guitar. But, there are also some little tricks — or, as Jimi Hendrix liked to say, “Gimmicks, man…it’s always the gimmicks!”— that you can do on guitar, and they always work. People will go, “Whoa!” every single time!

One of the gimmicks I love to use is the toggle switch trick, most effective on guitars with separate volume controls for each pickup, like a Les Paul, for example. Set the volume controls with the bridge pickup on full and the neck pickup completely off. While holding a note or a chord, flick the toggle switch back and forth between “on” (bridge pickup) and “off”’ (neck pickup) to produce a manually controlled tremolo effect. You can devise cool rhythmic syncopations based on the way you flick the toggle back and forth.

A great twist on this is to add a wah pedal and sound a series of notes via hammer-ons with the fret-hand only — all the while flicking the toggle in the rhythm of the melodic line and also rocking the wah. Dave Meniketti from the heavy metal band Y&T did it the best, in my opinion. Ace Frehley did it on Kiss-Alive! and of course, Randy Rhoads would use this technique all the time.

Another gimmick that always goes over great is to bend the G string behind the nut, as Jimmy Page did in his epic solo breakdown on “Heartbreaker.” I like to hit a high harmonic on the G string and then push down hard on the string behind the nut, raising the pitch as much as two whole steps. It sounds like a whammy bar — except that the note is going up instead of down — and it is easily done on all non-tremolo guitars.

Another “effect” that I love — one that has been in use since the very beginning of the use of guitar distortion, way back in the Fifties — is the big, aggressive slide up the bottom two strings to the highest part of the fretboard and then back down, as Randy would do to kick off “I Don’t Know.” You will hear Hendrix use this technique on the live recording of “Wild Thing” from the Monterey Pop Festival — bending the string at the apex of the slide, which yields a kind of “Rhinoceros roar” sound. Try adding the toggle switch trick as you slide back down for another variation on the effect.

These are all little tricks that serve to add to the vibe and attitude of your guitar playing. While you are dazzling someone with awesome technique, you can always throw in tricks like these to take your solo in a new direction (and get an extra wow). The idea is to play things — and do things — that people will remember, and remember you for.

With many of my favorite guitarists, what got my attention was not just their playing — it was their whole presentation and package. The played how they wanted, dressed how they wanted, got feedback from their amp and even smashed up their guitars! That, to me, is real rock and roll! I’m not recommending that you smash your guitar... but if you are playing in front of 200,000 people, and, in the heat of the moment, you feel like smashing your guitar onstage — or doing something really wild and unexpected — I say go for it, you have won me over! It’s all about doing whatever is necessary to get the feeling and attitude of rock and roll across to your audience.