Add fire to your pentatonic phrasing with this lesson in Jimi Hendrix's soloing approaches

We might never reach Hendrix levels of god-like genius on the guitar, but how he phrased his leads is a lesson to us all. Here, we look at four examples that will expand your blues vocabulary

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

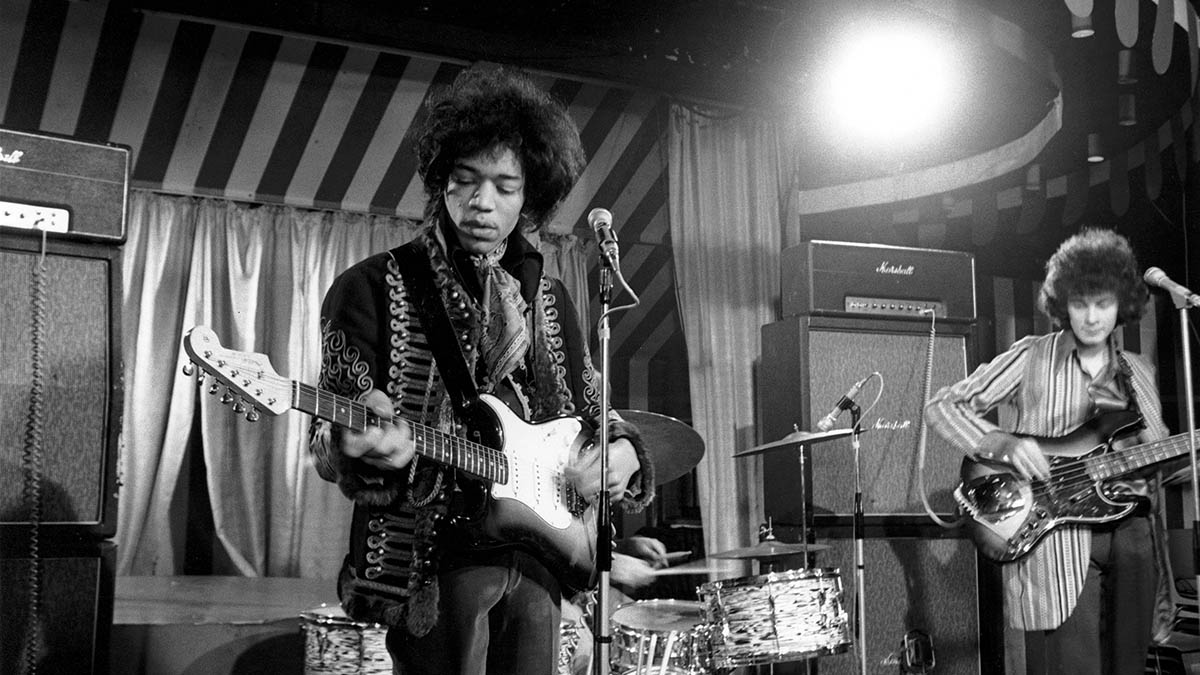

Jimi Hendrix was among the most significant musicians of the 20th century. For many, he was the ultimate electric guitar player, with an innate understanding of previous generations of guitar masters, along with a clear vision of how he could interpret this music in his own personal and dynamically charged way.

Jimi’s playing was bold, hip, at times brutal and at times sophisticated. His lead playing was as explosive as it was beautiful, with his flamboyant multifaceted style perfectly suited to the new sounds of the ’60s. While guitarists had used effects before, no one player assimilated these new sounds in such a compelling and cohesive package.

Fuzz, wah, feedback, whammy bar dives, sirens and wails, reverse guitar, echo, stereo panning and phasing, it’s all there on the few albums he released in just a four-year flurry of creativity as a band leader, before his tragic death in 1970, aged just 27.

In this lesson, we’re looking at Hendrix’s masterful pentatonic phrasing. We start with a selection of Jimi-inspired lines dividing the fretboard into five areas, or positions. As the minor pentatonic scale forms the basis for a huge amount of Hendrix’s soloing vocabulary, each line relates directly and is derived from its associated CAGED form, in this case in the key of E minor (E-G-A-B-D).

While the pentatonic is definitely at the core of each idea, we are by no means restricted to these five notes exclusively, so you’ll see the occasional added 2nd (F#), 6th (C#) and bluesy flattened 5th (Bb).

The beauty of the five-position system is that it gives you some instantly identifiable visual, aural and physical landmarks when learning, and importantly memorising new ideas. A really good idea is to purchase an A4 folder with five pockets, or open five virtual folders on you computer, one for each position.

When you learn a new phrase or create one of your own, write it down and pop it into the appropriate pocket, or record it as a voice note. Every couple of weeks you can review your research, making note of which positions you favour and, crucially, which ones are a little on the light side.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Another great way to expand your knowledge is to improvise over an extended backing track but limit yourself to using just one of the five shapes pretty much exclusively, perhaps allowing yourself to use low and high octave versions of the same shape if you have enough range depending upon the key and number of available frets.

If you repeat this process for five minutes for each of the five shapes, in less than half an hour you will have explored the fretboard in its entirely. You get nowhere by brushing stuff under the carpet, so once you spot a particular weak area, or fretboard ‘blind-spot’ you can then take remedial action to balance out the strong and the weak.

Technique focus: bending and vibrato

When adding vibrato to a bent note you’re basically bending and releasing so it’s essential that you reach your intended higher target pitch accurately. To sound authentically Jimi-like, add wide and slow vibrato but with control. The bending motion should come from a rotation of the forearm, rather than from the fingers alone.

Unison bending is one the most identifiable of Jimi’s soloing techniques. What we’re aiming to achieve is two notes at the exactly the same pitch, the higher note fretted with the first finger on either the first or second string, while the third finger frets the note a tone below the target note on the adjacent string, bending up two frets to create our unison.

Jimi then adds vibrato to the bent note to create a thick oscillating effect. Perhaps his most unique bending idea was the exchange bend. You push two strings up at the same time while only sounding the highest.

Once you’ve bent both strings, sounding the highest string on the way up, you shift the weight across, exchanging the pressure as you do so and sound the lower string as you release the bend, so one bend goes up and one bend comes down. What better excuse to watch some live Hendrix footage and see the process in action.

Example 1. Fiery Hendrix positional phrases

We begin with a set of Hendrix inspired predominantly minor pentatonic lines in the key of E minor (E-G-A-B-D). Each example outlines one of the five CAGED forms that map out the fretboard, starting with the highest ‘E’ form and working its way downwards to the open E position with a phrase for each.

Identify the repetitious patterns and ascending/descending sequences in each, along with expressive devices such as bends, hammer-ons, pull-offs and vibrato.

Example 2. Horizontal motion

This short and snappy example showcases Jimi’s fluency with horizontal motion, moving the same slur-slide combination along the length of the first string.

When used in conjunction with positional playing, this approach will allow us to connect all the shapes together to create one big cohesive whole that allows for free improvisation.

Take care to eliminate extraneous open string noise here, muting all of the unused idle bass strings.

Example 3. Rhythm guitar riff

Here is the rhythm guitar riff against which the previous examples are played. While such a lot of attention is placed on Jimi’s incredible lead playing, he was also a stunning rhythm guitar player.

Here we’re toggling back and forth between a low bass line and a higher, punctuating chord fragment. Pay attention to the percussive muted notes, as these really assist with the bounce and swagger of the line.

Example 4. Full solo

We end this study of Hendrix’s lead playing with a solo against a classic rock-style blues in E minor, full of pentatonic phrases. In this solo, we once again exploit each of the CAGED forms, although here we’re using these shapes in ascending order, beginning in the open position with the ‘E’ form and moving up the neck every two bars to take in the D, C, A, G and highest ‘E’ shapes in order.

You’re not duty-bound to follow such a regimented development in your own solos, but this is a great challenge to establish which areas of the fretboard are your most familiar comfort zones, and which areas feel most foreign and alien to you.

John is Head of Guitar at BIMM London and a visiting lecturer for the University of West London (London College of Music) and Chester University. He's performed with artists including Billy Cobham (Miles Davis), John Williams, Frank Gambale (Chick Corea) and Carl Verheyen (Supertramp), and toured the world with John Jorgenson and Carl Palmer.