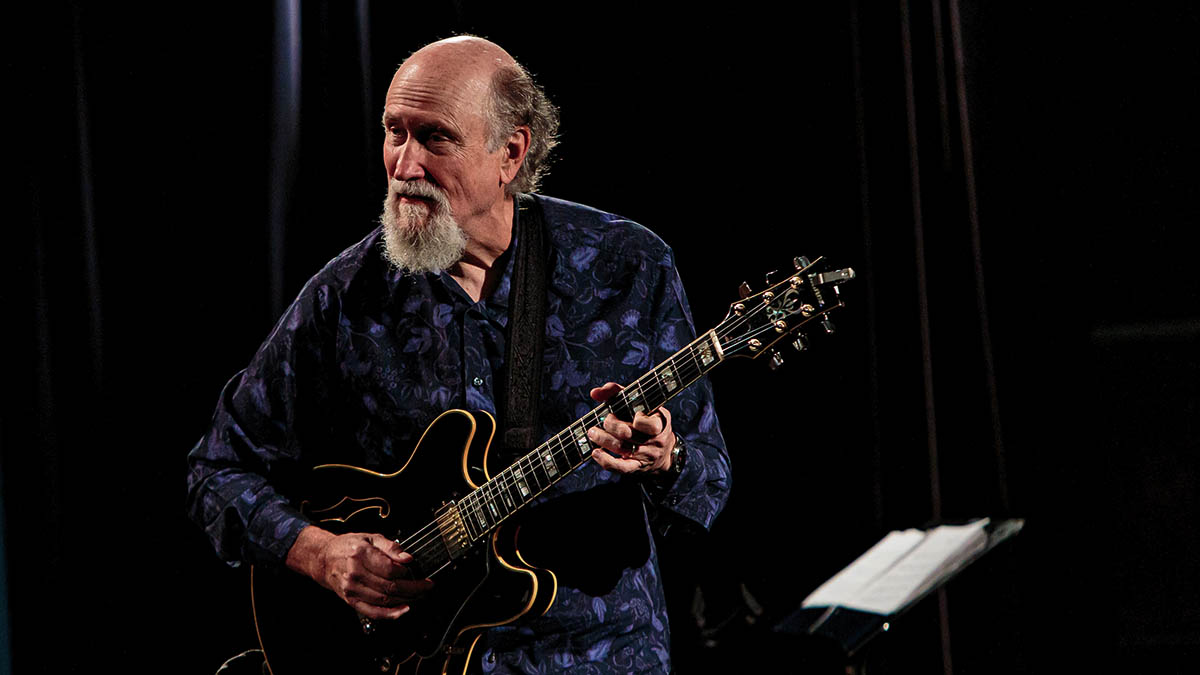

With credits spanning Miles Davis to John Mayer, John Scofield is one of jazz guitar’s most idiosyncratic players – and his mind-bending solo phrasing is a must-learn

A John Scofield lesson is a lesson in melodic choices. In this tab and audio lesson, we dive into his genre-spanning style to hone your jazz chops

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With a career that spans almost five decades, John Scofield’s style has continued to evolve, encapsulating the best elements from jazz, rock, blues, funk and soul, to create a sound that is ever developing but which always sounds unmistakably like ‘Sco’.

John picked up his first guitar aged 11, and started off by learning the hits of the day from the radio. By his early teens he developed a keen interest in rock and blues guitarists such as Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and B.B. King, influences that can still be clearly discerned in his playing to this day.

But by the time he reached 16, Scofield was a fully fledged jazzer, with a small but intelligently selected record collection that included legendary guitarists such as George Benson and Pat Martino, along with classic jazz and bepop artists including Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

Scofield attended the prestigious Berklee College of Music and, by his own admission, had to really work hard to make the progress that he desired. This determination and focus has remained consistent throughout his career, with a constant drive to remain fresh, current and cutting-edge.

After graduating, John came to the attention of drummer Billy Cobham, with a band that included both Michael and Randy Brecker. This in turn led to work with a host of notable artists such as George Duke, Stan Getz and Chet Baker.

Scofield’s big break came when saxophonist Bill Evans suggested him to trumpeter Miles Davis, working alongside the equally amazing guitarist Mike Stern on the road and performing on the albums Star People, You’re Under Arrest and Decoy.

But it was inevitable that John would go solo, and for almost 40 years Scofield has enjoyed a remarkably successful career as a bandleader and composer, with an extensive portfolio of releases in a wide variety of styles and contexts.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

John’s note selection is impeccable, with intelligent melodic choices, and lines that effortlessly weave through even the most complex changes. He has a remarkable sense of balance in terms of consonance and dissonance, blending stable inside notes with outside chromatic decorative tensions and embellishments, in a completely convincing and compelling way.

One melodic option that John and his fellow jazz, fusion and modern blues contemporaries like to utilise is the half-whole symmetrical scale, the second mode of the diminished scale which is usually built from a combination of alternating whole (two-fret) and half-step (one-fret) leaps.

This second permutation flips the pattern around in a chain of tone-semitone-Tone-semitone jumps until reaching the octave (R-b2-#9-3-#4-5-6-b7), providing us with a total of eight notes (C-Db-D#-E-F#-G-A-Bb) and giving us a huge range of harmonic options.

Our study looks at this scale and highlights how John, alongside other notable jazz and fusion greats such as Mike Stern, Allan Holdsworth, modern gypsy jazz master Adrien Moignard, and progressive and educational legend Joe Diorio all employ this scale. We look at a selection of lines, ending with a full solo all based around this remarkably fruitful melodic and harmonic device. As always, enjoy!

Get the tone

Amp Settings: Gain 6, Bass 4, Middle 5, Treble 5, Reverb 3

John plays Ibanez guitars, specifically his JSM100 signature guitar. Guitar amps are Vox or Fender combos with light overdrive. Explore all your picking options, as John moves his picking hand from right up by the bridge to over the neck pickup as the music dictates. Go easy on the gain, too, as this will limit your dynamic range – the last thing we want here.

Example 1. Fusion-Jazz Lines

We begin our exploration of the half-whole diminished scale with five lines in the key of C (C-Db-D#-E-F#-G-A-Bb), all located against an underlying static C7#9 groove (C-E-G-Bb-D#). We begin with string-skipped slippy idea from Sco, before moving onto intervallic and legato lines from Mike Stern and Allan Holdsworth. We next present a chordal idea from Adrien Moignard, before rounding off with an angular line from the intervallic master, Joe Diorio.

Example 2. Half-Whole Intervallic Patterns

Next up, we’re looking at a selection of intervallic and sequenced patterns using that same C half-whole diminished scale, once again over a C7#9 chord.

Due to the symmetrical nature of this note pool, it’s helpful to break the pattern down into smaller movable chunks. 2a) breaks the scale down into a six-note moveable pattern than can be repositioned around the guitar in minor 3rds (three frets) or any multiple of three-fret leaps. 2b)-2g) presents a selection of patterns juxtaposed into a small portion of this scale.

Each of these ideas could be transposed around the guitar in three, six or nine-fret leaps, both up and down. In 2h) we see a favourite device of Scofield, turning a three-notes-per-string scale fingering into a two-notes-per-string ‘faux’ Pentatonic-like pattern.

While these fingering don’t create actual pentatonic scales per-se, with five notes to each octave, what they do achieve is a physical resemblance to our finger and phrasing-friendly old-faithful two-notes-per-string patterns, allowing Scofield to transfer some of the phrasing and bouncy rhythmic ideas he developed from many years of playing blues guitar into somewhat more sophisticated melodic and harmonic material.

Example 3. Full solo

We round up this look at Scofield’s playing and his use of the half-whole diminished scale with a solo based around a funky fusion track against C7#9 and A7#9. While this could be considered a static tonality shift, remember that these patterns can all be moved in three-fret intervals, including each of the available chords.

Therefore, both C7#9 (C-E-G-Bb-D#) and A7#9 (A-C#-E-G-B#) could be considered joint members of the same half-whole family, albeit with some enharmonic respellings.

One benefit of this symmetrical thematic development is that you can make a little go a very long way.

As always, once you’ve learnt this solo, just improvise along with the backing track using your own ideas, or any of our melodic cells, and see if you can create an solo taking pieces from these phrases and creating variations and developments along the way. It’s how Scofield would have built his own harmonic armoury, so why not give it a go?

John is Head of Guitar at BIMM London and a visiting lecturer for the University of West London (London College of Music) and Chester University. He's performed with artists including Billy Cobham (Miles Davis), John Williams, Frank Gambale (Chick Corea) and Carl Verheyen (Supertramp), and toured the world with John Jorgenson and Carl Palmer.