The Bleak, Ominous Second-Inversion Minor Chord

Tell an engaging story and make a powerful statement with second-inversion minor chords.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Continuing our exhaustive (and perhaps exhausting) study of chord inversions and their practical applications in progressions, I’d like to cite some recognizable examples of interesting and musically effective ways in which successful pop songwriters have employed a second-inversion minor chord, which is a minor chord with its fifth in the bass. Like the first-inversion minor chord we looked at last time, second-inversion minor has a dark quality that, to me, sounds ominous and bleak, and which is probably why it isn’t used as commonly as its bright-and warm-sounding major counterpart. But in music, like any other art form, you need contrasts to tell an engaging story and make a powerful statement. Major chords, vanilla ice cream and blue skies alone won’t create drama.

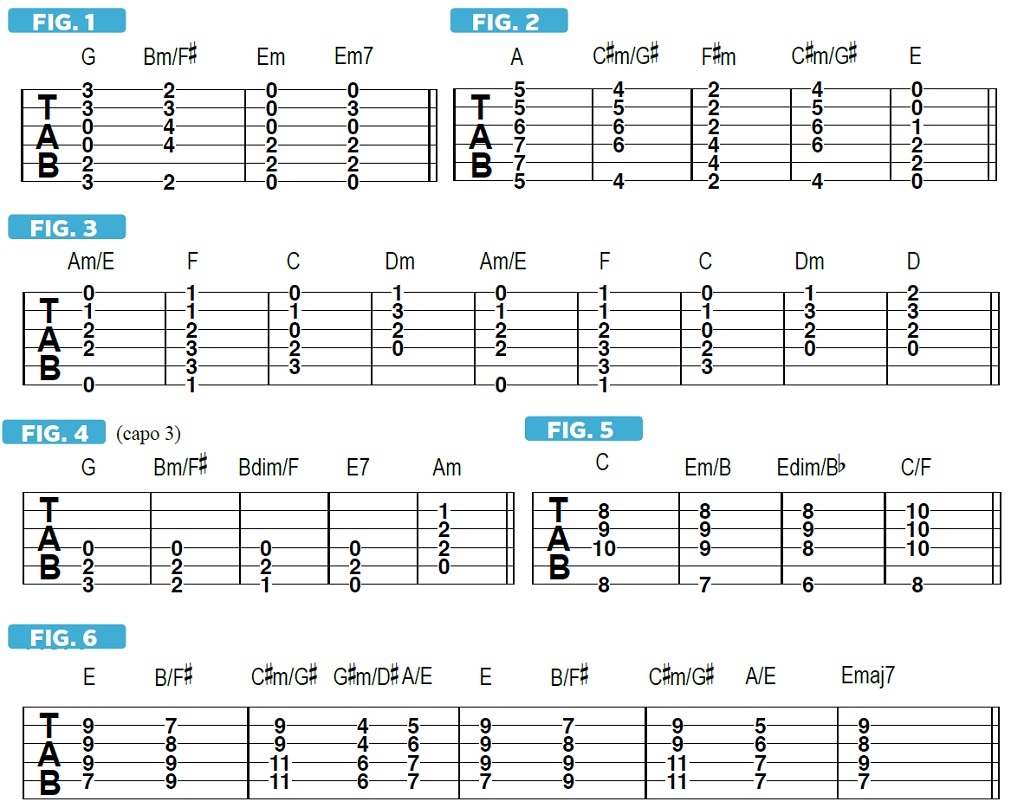

Outside of classical music, the first example of a great application of a second-inversion minor that comes to mind is the second chord in the Beatles song “A Day in the Life.” Strumming his acoustic guitar, John Lennon begins the song, and each of its verses, on an open G chord and proceeds to walk down to Em, via Bm/F#, using the voicings illustrated in FIGURE 1. The thoughtful and brilliant composer could have just as easily played a straight Bm, or the more cliche passing chord D/F#, but that sounds a lot tamer, doesn’t it? And too much like “Free Bird” (which wasn’t written yet).

A few years after the Beatles broke up, Bruce Springsteen penned what many consider his greatest masterpiece, “Born to Run,” which, during its pre-chorus, features a similarly haunting second-inversion minor chord used in a bass-line walk-down (on the lyric “Highway 9”). Here, the progression goes A, C#m/G#, F#m (all barre chords), then back to the chilly C#m/G#, followed by a warm and much welcomed open E chord, as in FIGURE 2.

Article continues belowAnother goosebump-inducing example of a second-inversion minor chord’s use in a popular song, and in a different way, can be found in “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” by the Band, which we touched upon in the previous lesson on second-inversion major chords. In this case, I’m referring to the beginning of each pre-chorus (first heard at 0:16, with the lyrics “In the winter of ’65”) and the repeating chord changes Am/E F C Dm, as in FIGURE 3, for which the bass line walks up instead of down. When playing this low Am/E voicing, avoid hitting the open A string, as that will sound muddy in this register, and include only the low E bass note below the fretted notes. This may be accomplished by muting the A string with the tip of your fret-hand middle finger as if frets the D string, or by selectively fingerpicking the strings. (Or you could instead strum a fifth-position Am barre chord without barring the low E string.)

At the risk of being verbally stoned to death by GW readers/viewers for referencing yet another oldie example, I’d like to quickly point out the sparsely voiced second chord in each verse of Simon & Garfunkel’s “Homeward Bound,” Bm/F#, which was transposed up a minor third, via the use of a capo, like in FIGURE 4, and arpeggiated. These first couple of chord changes also bring to mind the piano part that begins “Home Sweet Home” by Mötley Crüe, approximated on guitar in FIGURE 5.

In the first verse of “Under the Bridge,” Red Hot Chili Peppers guitarist John Frusciante intentionally omits the low sixth-string root notes from both major and minor barre chords, thus putting them in second inversion. This adds to the musical appeal of the progression, no doubt by making the voicings sound more sophisticated and the parallel fourth and fifth intervals less power chord-y, similar to what Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder did with his first-inversion major chords in “Better Man,” which we looked at recently. FIGURE 6 illustrates the aforementioned second-inversion voicings.

Senior Music Editor "Downtown" Jimmy Brown is an experienced, working guitarist, performer and private teacher in the greater NYC area whose professional mission is to entertain, enlighten and inspire people with his guitar playing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.