Expand Your Soloing Vocabulary with the Half-Whole Symmetrical Diminished Scale

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last month, I discussed ways for guitar players to expand their improvising vocabulary. I’m a big proponent of transcribing other musicians’ solos, including those played on other instruments, such as the saxophone, trumpet or piano, for example. This has been a lifelong endeavor for me, one that I still enjoy and feel that I greatly benefit from every time I pursue it.

I started out as a blues-rock guitarist and spent a lot of time figuring out licks by such great players as Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, B.B. King and Buddy Guy, and I still love those guys. I eventually got some jazz records and tried to play along with them, but I got completely lost. It seemed that the vocabulary of jazz was so much more difficult—not necessarily better, just different. I favored the simplest stuff, and I still do, because it grabs my heart, and music is a language of the heart. But I was very intrigued by jazz and yearned to expand my knowledge of the guitar and music by studying that language.

For the longest time, I thought I would never get it. I attended Berklee College of Music, and even though its programs were excellent, I never imagined I could become fluid in jazz. It was a language that was very foreign to me, and for the longest time I couldn’t get any emotion behind my playing in it, but I think I eventually managed to do so.

Studying jazz benefited my blues and rock playing, in terms of inspiring new ideas and musical ways of expressing myself. But it didn’t happen overnight and took a lot of work. In time, I knew the language well enough that I could communicate in the same way we speak. I didn’t need to think about it so much anymore and could just express myself.

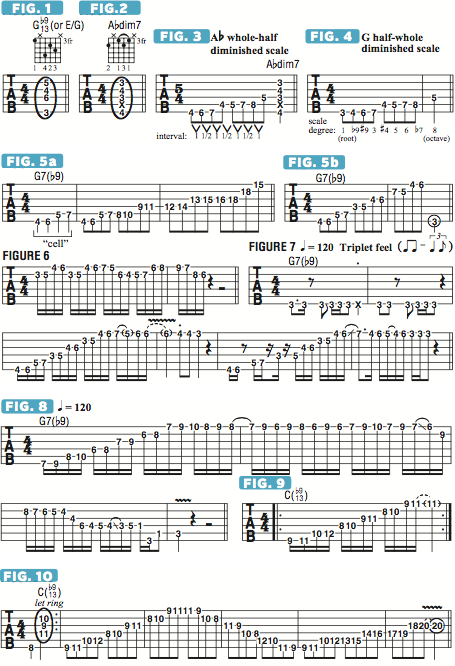

I learned some very valuable stuff from a brilliant keyboardist named Kenny Kirkland, who had played with Sting, Branford and Wynton Marsalis, John Scofield and many others and sadly died at the young age of 33. Kenny taught me a very cool lick built from the G half-whole symmetrical diminished scale (G Ab Bb B C# D E F), which is built on alternating half steps and whole steps. A chord that fits well with this scale is G(f9-13), which may also be thought of as an E triad over a G bass note (E/G; see Figure 1).

Another incarnation, or mode, of this scale is the whole-half symmetrical diminished scale. Figure 2 depicts an Abdim7 chord, and Figure 3 shows the Ab whole-half scale (Ab Bb B C# D E F G), which is comprised of the very same eight notes as the G half-whole scale (see Figure 4) and rooted on Ab instead of G. Kenny showed me a cool, four-note melodic shape, or “cell,” based on the G half-whole scale that works well over G(b9-13). Figures 5a and 5b show the shape ascending in half steps, and Figure 6 demonstrates how it may be moved around chromatically. Figures 7 and 8 offer two examples of how I might typically employ this cell when improvising. If we were to move everything up a fourth, to C(b9-13), we get the patterns shown in Figures 9 and 10.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!