“I met Billy Cobham on a Campbell’s Soup jingle and doing an Avon jingle with Herbie Hancock. It was an amazing time”: A pre-fame Stanley Clarke took chance after chance at a 1974 session with Aretha Franklin – and helped define a soul classic

Clarke's early session career offered tantalizing glimpses of his technical prowess and innovations, and hints of how he would transform the low-end landscape with Return To Forever and his own solo albums

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

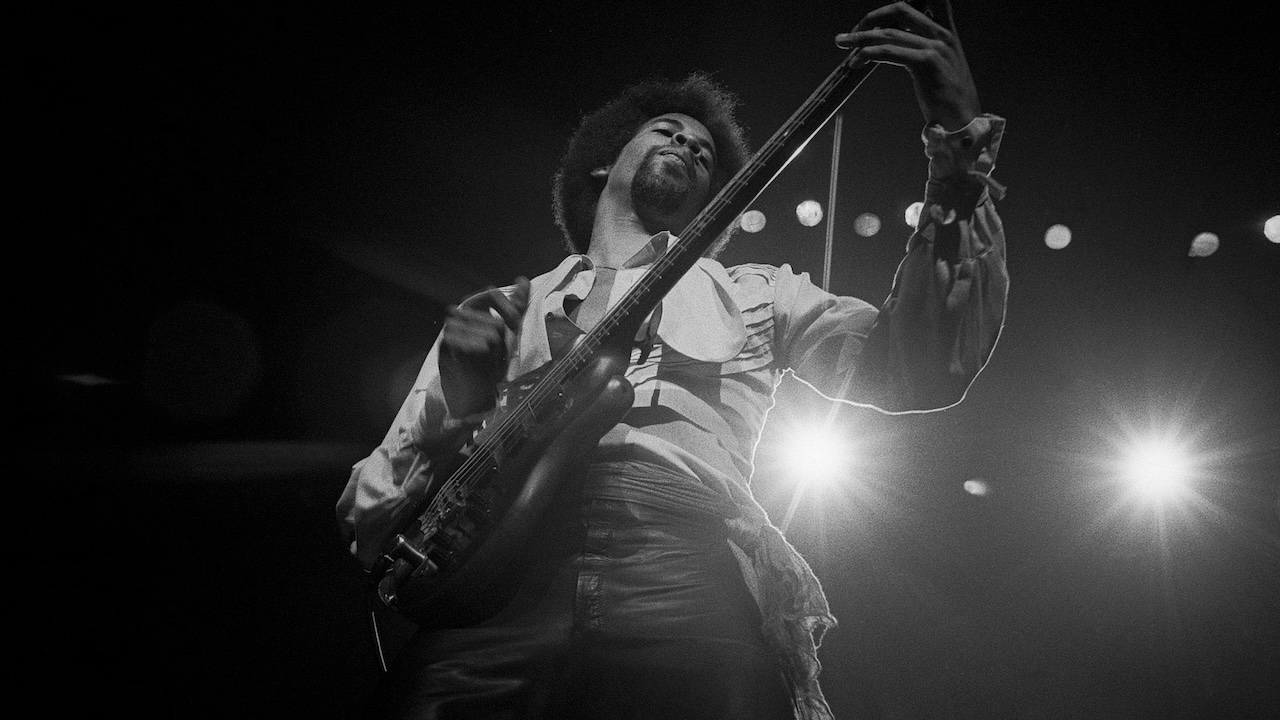

A lesser-known aspect of Stanley Clarke’s early career in the 1970s is that while he was in the throes of revolutionizing the bass guitar, the Philadelphia native had a solid three-year run as a groove-minded New York City session musician.

“I would do four sessions every day,” said Clarke in the May 2017 issue of Bass Player. “I was paying $35 a month in rent and I'd make that in the first hour of my first session! I remember meeting Billy Cobham on a Campbell's Soup jingle and doing an Avon jingle with Herbie Hancock. It was an amazing time.”

Those early session dates offered glimpses of Clarke's technical prowess and innovations, and hints of how he would transform the low-end landscape with Return To Forever and his solo albums.

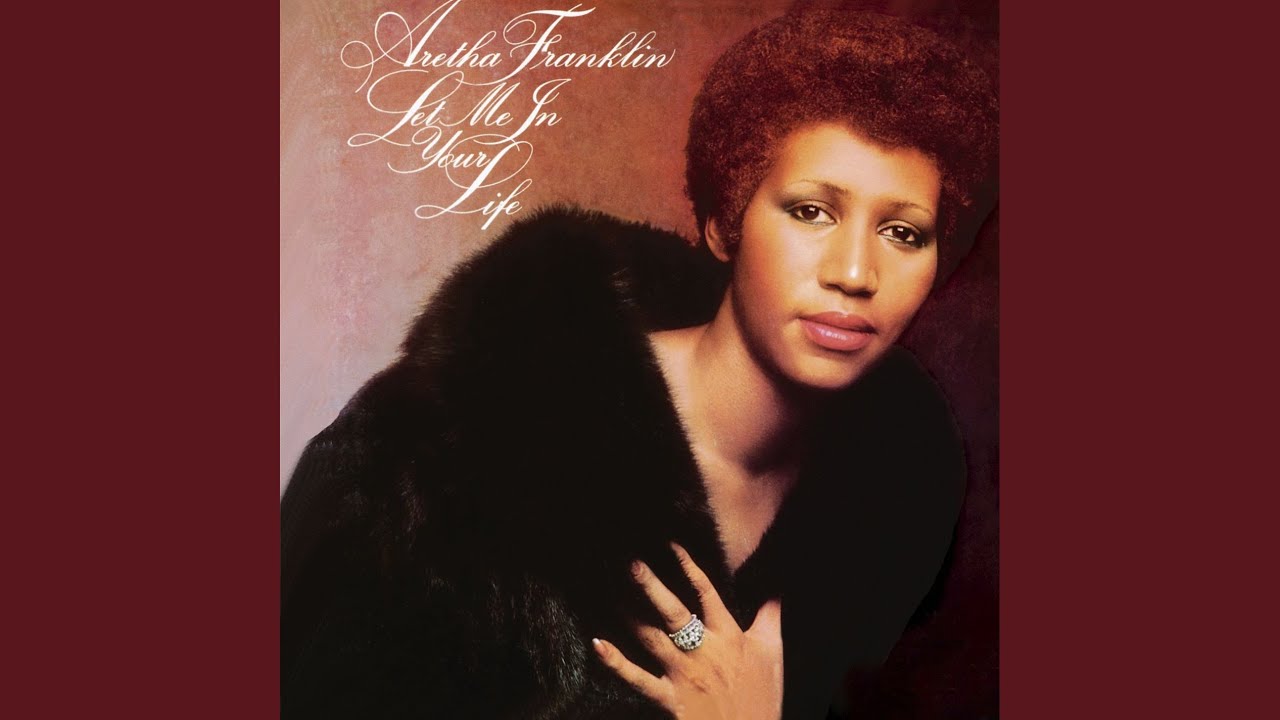

Perhaps the best example is Aretha Franklin's cover of Bill Withers’ Let Me in Your Life, from her 1974 album of the same name.

The album also features studio bass legends Willie Weeks and Chuck Rainey (including Rainey's peak performance on Until You Come Back to Me), but it was Stuff bassist Gordon Edwards who sent Clarke in to sub for him.

The session took place in September 1973, at Manhattan's famed Atlantic Studios on the corner of Broadway and 60th Street.

In the main room, opposite the strings, Clarke was set up between drummer Rick Marotta and guitarist David Spinozza, with arranger/electric pianist Eumir Deodato, organist Bob James, and percussionist Ralph MacDonald nearby. Franklin was in a separate vocal room, while Donny Hathaway was in another room on acoustic piano.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

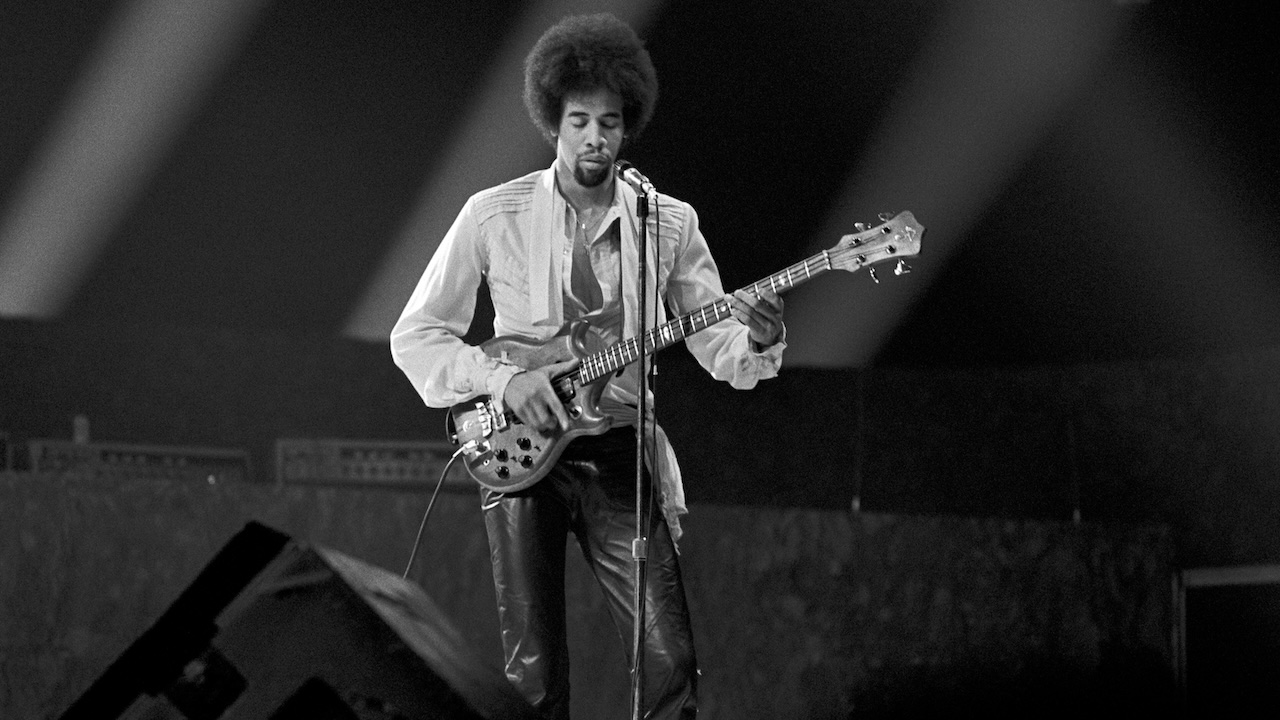

Deodato provided a chart that was mostly chord changes with some notated cues. The ensemble did two or three run-throughs and one or two recorded takes. Clarke played his Fender Precision with flatwounds, recorded direct via a tube DI, as well as a miked Ampeg B-15, “to get some grit.”

The track begins with a two-bar intro that includes Deodato and Spinozza riffing, leading Clarke to boldly jump into the groove with his upper-register fill in the second measure.

“I was young, cocky, and confident, so I went for it. The New York session scene at that time was friendly to the next hot young player coming up, and I was that guy on bass – which is smart, because to move music forward, you always have to acknowledge what the youth bring to the table.”

“This was particularly true of Aretha's producers on the session, Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin, and Tom Dowd. They always had their eyes on the young guys and the next new sound, and they dug what I was doing. Wexler liked that I took chances. He listened to the take and said, ‘Yeah! That's a bass track!’”

Clarke pivots between the tonic G and F in the hard-driving A section, with some open-E pickups. He also uses chromaticism when moving to the IV chord C for the second time at 00:43.

“There was a language of contemporary R&B at the time created by masters like drummer Bernard Purdie and guitarist Cornell Dupree, and for me, on bass, James Jamerson and Chuck Rainey – and we were all fluent in it.

“We had the rhythms and the licks down from listening to those guys. But at the same time, we added our own subtle twists, as newer guys with varied influences. I remember Rick's hi-hat feel was slightly different from Purdie’s.”

For the first B section at 00:53, Clarke unleashes a series of descending fills in the back half of each measure. Of note is how he starts his run on the C of the Am7b5 and moves to progressively higher starting notes in the successive chords. Also key is how he uses the open G, D, and A strings to navigate these considerable spans.

“There was space after the downbeat, and I'm thinking David, Rick, and the keyboardists aren't doing anything, and even the string line is whole-notes, so I went for it! I thought that section needed some movement, and it came out naturally and quickly, without a lot of thought.

“I was a jazz musician; I knew chords and I knew which notes to pick. I was fearless and everyone had made the session so comfortable for me. I remember Rick looking at me wide-eyed and then nodding.

“The other factor was that Aretha is more aggressive in the A section, which we all responded to, but in the B section she's more passionate and pleading. I wanted to play something beautiful and emotional on the bass in response.”

As for the open-string use, Clarke added, “My whole approach to basslines goes back to my roots on acoustic bass; utilizing open strings is a common device for getting around on the upright. But another part of my open-string use was for tonal purposes.

“As a melodic-minded player, I liked to have ringing notes, and back then, flatwound-strung electric basses had a short, thumpy sound, which is why I liked to have a miked amp when recording.”

Clarke goes on to play with a bit more expression via slurs, slides, and hammers in D. This leads to the outro at 02:53, which rides the A-section pocket. With the fade looming, he submits one more greasy, upper-register idea at 03:11.

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.