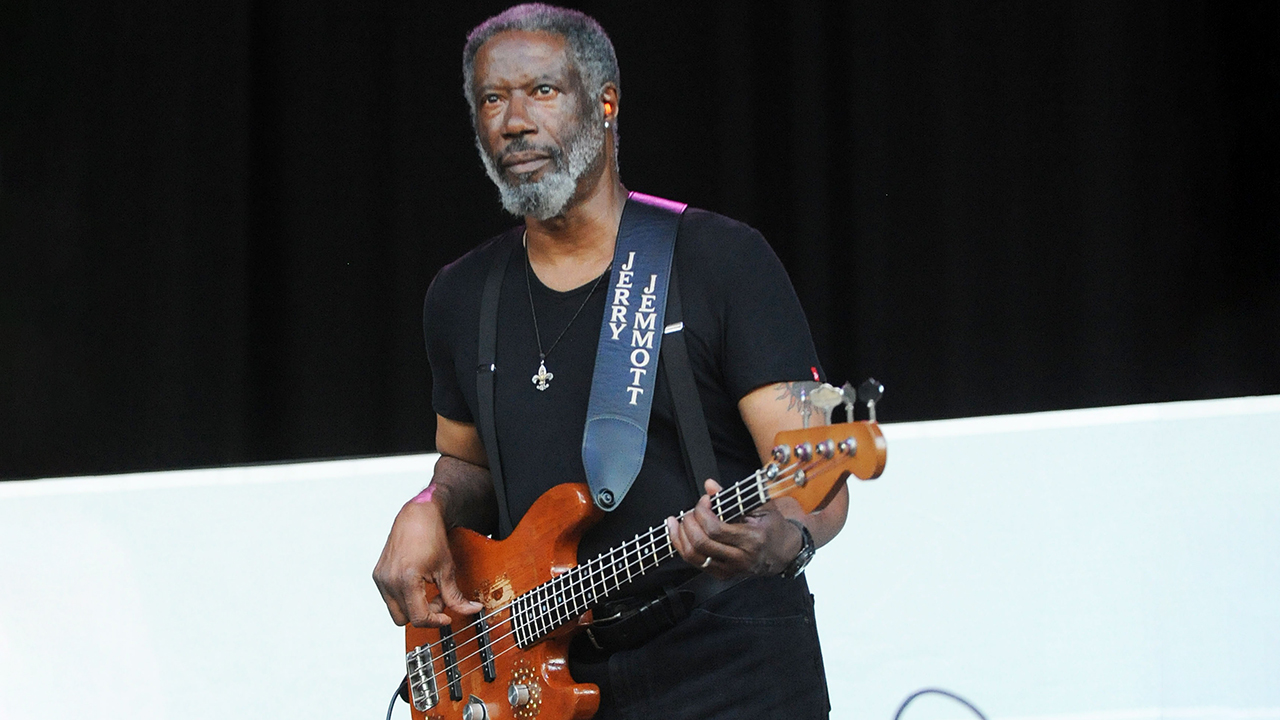

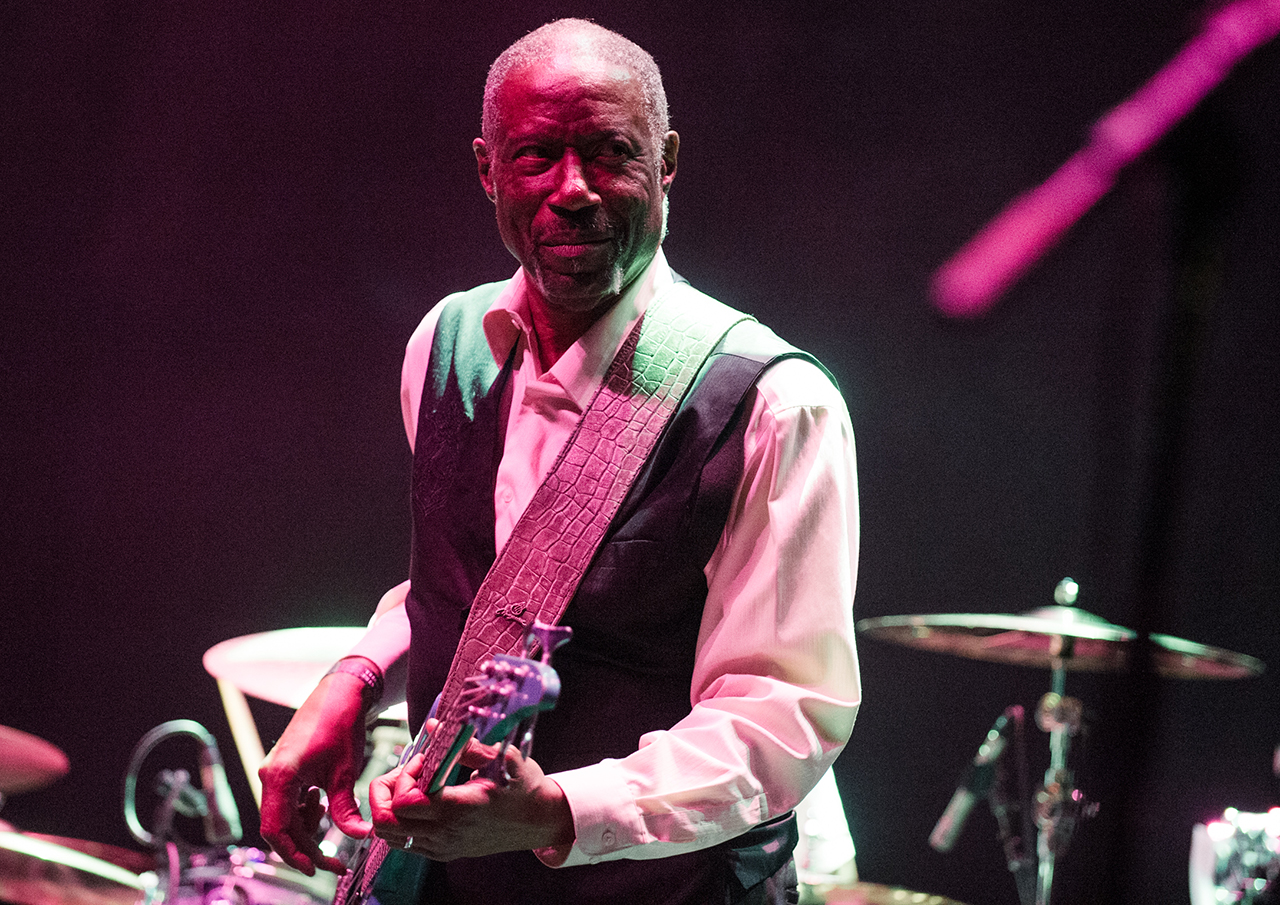

“I said, ‘We aren’t getting paid properly. I’m going back to New York.’ Duane Allman said, ‘I’m gonna go home and start a band with my brother’”: Jerry Jemmott played with B.B. King and George Benson – but two car accidents influenced him the most

A childhood head injury meant the session icon had to find his own way of making music. But after working with King, Aretha Franklin, Benson, Roberta Flack, and many others, he’s proud to be a poster boy for not knowing what he’s doing

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jerry Jemmott has experienced two near-fatal car crashes. The first took place when he was a child – and it led to him taking up the bass.

“My hearing was so bad after the accident, I had a hard time hearing the bass,” he says. “But that’s why I chose it!”

He approaches the challenge with a unique philosophy: “If I made a mistake I thought nobody would hear it, because I couldn’t. What motivated me was that I felt safe approaching the instrument.”

Even though Jemmott struggled to hear, he knew he could feel. That’s how he became one of Atlantic Records’ favored session players in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, interchanged with Ron Carter, to record for Aretha Franklin, B.B. King, George Benson, King Curtis, Roberta Flack, Gil Scott Heron, and others.

But in 1973 he survived a second car accident, which left him physically and mentally unable to play for three years. After becoming a Buddhist, he started playing again, and more sessions and a solo career followed. He’d had another change of philosophy too: “My idea was to become a better version of myself – I’d realized I didn’t know shit!”

Jemmott’s recording career has tapered recently. “I’m still writing, arranging, and composing, but right now there’s no outlet. When I was in the studio I had an outlet all the time. It’s different now.”

But he’s not done; since 1999, he’s worked with the Color Sound program that helps young players with learning disabilities associate notes with colors. “Stress is a hell of a thing,” he says. “It affects your time, but it also sparks your creativity.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“There’s good stress and bad stress. You want to eliminate the stress of unknowing. Knowledge is helpful in terms of making you feel comfortable. It comes out in your playing – you can hear it.”

You suffered a head injury in a childhood car accident. How did it impact you once you picked up the bass?

After the accident, music, and everything, was different for me. I don’t remember the accident itself; they told me I was hit by a car, went up two stories and came down on my head. I was in the hospital for weeks.

I was completely withdrawn and living the life that you’d expect from somebody who had head injuries. When I listened to music I’d heard before the accident, all of a sudden, the bass stood out to me. I said, “I want to do that.”

My mother was astounded because, before that, I’d never wanted to do anything! But the bass gave me something to live for. The way it moved and affected the music, I said, “I can do that.”

I pictured being at the back of the bandstand, which suited my personality. I didn’t want to be in the spotlight.

Did your brain injury affect your ability to learn?

I had a private teacher who came to my house every week, but I wouldn’t practice. I hate practice – I’d rather play along with music. I’d open the book an hour before he came over, look at it and play. He said, “You sound great!” I could read the music, but I couldn’t hear a goddamn thing! I couldn’t tell a B from a B flat.

You were discovered by King Curtis, and became a session bassist for Atlantic Records in the late ‘60s. What kind of gear were you using?

My goal was to be a session musician, but I knew I’d have problems – I couldn’t remember shit, and I couldn’t hear stuff. But I still had a desire to play. I said, “I will never be the best, but I could be among the best.”

I said, ‘We aren’t getting paid properly. I’m going back to New York.’ Duane Allman said, ‘I’m gonna go home and start a band with my brother’

When I switched from upright to electric bass in 1964, I got a Zim Gar bass and an Epiphone flip-top amp that sounded crappy! Eventually, I got my first Fender Jazz Bass and an Acoustic amp at a pawn shop. That was it for me.

The Jazz Bass was stolen early in your session career, right?

Yeah. An engineer told me, “Jerry, we can rent you a bass.” They couldn’t find a Jazz Bass so they rented me a P-Bass, and said, “You had a really hot sound. You gotta find it again.” When I played the P-Bass they said, “No matter what you’re playing, you’re fine!” That was a revelation – it taught me never to be hung up on instruments.

What was it like recording with B.B. King and George Benson?

It was killer! Playing with those guys was me playing with my heroes. And in the ‘30s and ‘40s, they would hide away all these jazz musicians to make those records, so what I was doing was nothing new.

How about Aretha Franklin?

She was a dream come true. I’d listened to her coming up, before she was a pop star. In 1968 I got a call from Jerry Wexler, who said, “Just bring your bass. You’ll get paid for two sessions. You might play, you might not, but I want you to be there.” And that’s how I got into it with Aretha.

They’d called me down because they’d been on one song for three hours and couldn’t get it. Jerry said, “Go in and do what you can.” After three takes I got up to leave, but they said, “Oh no, you stay here!” And I worked for the rest of the week.

Everything spiraled after that. When Jerry called me to do a session he had an idea of what I would do. I could always come up with something.

You had a close relationship with Duane Allman, who also worked as a session player for Atlantic.

Duane was great. The first session we did together was with King Curtis. When they started sending me to Muscle Shoals, I think I made five trips, and Duane was on three or four of them.

On the last session we had down there, I said, “I’m getting tired of doing these sessions. We aren’t getting paid properly. I’m going back to New York; I’m just gonna do jingles, TV work, and maybe some recordings for people. Then I won’t feel like I’m being ripped off all the time.”

Duane felt the same way – he said, “I’m gonna go home and start a band with my brother.” That was 1969, and it was the last time I saw Duane until we did Herbie Mann’s Push Push album, right before he was killed in ’71.

They’d call me when they couldn’t get Ron Carter, and call Ron when they couldn’t get me. We both ate the same food

There’s been a lot of debate about this: Ron Carter is credited for Gil Scott Heron’s The Revolution Will Not be Televised, but it’s suggested that you played bass.

Oh, yeah – the credit is inaccurate! I play electric bass on that song, but Ron played on the rest of the album. He’s on the album, but I’m on that song. That’s why people get confused. They’d call me when they couldn’t get Ron, and call Ron when they couldn’t get me.

We both ate the same food, you know? Though his digestive system was a lot better than mine! I’ve had learning difficulties for my entire life; I couldn’t learn the regular way. I had to come up with a system where I see it, hear it, say it, sing it, and play it.

Can you remember recording The Revolution Will Not be Televised?

Of course! As a kid playing upright in the Village, I’d get on the train and play with poets, so it wasn’t a big stretch. Most producers were smart; they’d match the artist with a musician who’d translate their music with the most ease – this was the case here. That song was totally me, a flute player, and Gil.

In 1972 you were in another near-fatal car accident with Roberta Flack and her guitarist, Cornell Dupree. Given your history, that must have taken a heavy toll.

Oh, it did. It took my life away. All of us were diminished tremendously from that accident. Cornell died early and Roberta just passed away last year, but there was a lot of suffering as a result of that accident.

It haunted me emotionally for the longest time because I was driving the car. But I had to get to grips with it; but I couldn’t physically play because I was injured. Then when I did start again, I had to stop because I couldn’t handle it; I wasn’t right.

But it’s been 52 years since I became a true Buddhist. That brought me back to a sense of life and gave me the confidence and courage to pursue music again.

How did the experience change your playing?

I tried to be a better player. I enjoyed the process of teaching – sharing my music with others – but I was teaching theory out of a book. I didn’t know shit! So I put the book down and never pursued the teaching. I just kept on playing.

My thing was that I didn’t have time to learn; I wanted to play. Eddie Harris once said, “Music is the only profession where you can become successful and not know what you’re doing.” I’m the poster child for that!

Imagine a baby growing up with the idea that everything they see in color is a musical note, and they can create songs with the colors

In recent years your focus has been on Color Sound, which helps players who struggle to associate notes with colors.

It’s a way of connecting the dots – putting all the information you have about a note, chord, or phrase into words, so the words resonate and come back to you. It’s a way of following thoughts, reading them on paper, and duplicating the ideas.

It takes longer, and for an experienced musician it’s like going backward. But for a beginner it gives a foundation and an understanding of what the hell they’re doing.

Stress comes out in your playing, and listeners can hear it. You can’t fool anybody; and if you try to fool yourself, you can’t even do that! But we can learn to adapt. We learn to hide our deficiencies and inadequacies.

Learning brings you full circle to like who you are. You know what you’re here for and what you want to do. Getting your tools together gives you the apparatus for what you want to do.

All these kids are so wired with technology that we didn’t have coming up. They’re plugged in like the Borg from Star Trek! I can see my Color Sound thing on a phone – that will be great for children. I’ve been working on the software since 1999 on a computer the size of the Empire State Building, and now it’s on my iPhone.

How do you see the future of Color Sound shaking out?

The idea is to have an instrument that’s interactive at a very rudimentary stage. Imagine a baby growing up with the idea that everything they see in color is a musical note, and they can create songs with the colors. A wonderful thing!

Music is the envy of all the arts. Everybody loves music and everybody has music in them. We can all relate to music, and we all know color. So we’re putting these two things together. It’s totally accessible and agreeable to everybody on the planet.

- Learn more about the Color Sound program.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.