40 guitarists who changed our world since 1980

The players who revolutionized guitar technique and tone over the past 40 years

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1. Eddie Van Halen

WHAT HE DID: Like Jimi Hendrix a decade earlier, Van Halen caused guitarists to look at their instruments in an entirely new way, and, arguably, no single guitarist has had such universal impact since.

Playing together without having to compromise our sound was a dream come true

Eddie Van Halen

Eruption changed everything: Sure, it clocked in at less than two minutes and never came close to being a hit.

As presented on the first Van Halen album in 1978, it seemed like an instrumental introduction to You Really Got Me, the band’s debut single. But it was obvious to anyone who heard the Eddie Van Halen masterpiece that the world of rock guitar had changed dramatically.

As author Robert Walser wrote in his 1993 scholarly examination of heavy metal, Running with the Devil: “In 1978, Edward Van Halen redefined virtuosity on the electric guitar.” Frank Zappa put it more simply: he thanked Van Halen for “reinventing the electric guitar.”

That was 42 years ago, and guitarists are still reeling from the impact. Before Van Halen, guitar heroes were known mainly for their mastery of the blues and ability to pull a rich, vocal tone from their axes.

Some, such as Jimi Hendrix or Jeff Beck, were worshipped for their mastery of feedback and effects; others, particularly fusion players such as John McLaughlin and Al Di Meola, were celebrated for their speed.

With Eruption, Eddie Van Halen set new standards on both fronts. He not only ripped through demisemiquavers with a speed and clarity that made McLaughlin seem splay-fingered; his mastery of feedback, tremolo and pinged harmonics made his guitar sound as fluid as a synthesizer.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I was playing this way when we were playing clubs, and I remember what I used to do. I’d turn around. I didn’t want anyone to see how I was doing it

Eddie Van Halen

And when he used his two-handed hammer-on/pull-off technique to unleash a cascade of sextuplets at the end of his solos, you could almost hear jaws drop in amazement. Nobody had ever done that on a guitar before. No one even imagined it could be done.

Edward knew he was onto something big even before his band made its recorded debut. “I was playing this way when we were playing clubs, and I remember what I used to do. I’d turn around,” he said in 1982. “I didn’t want anyone to see how I was doing it.”

Wise move. Edward’s two-handed style was the most widely imitated guitar technique of the Eighties especially after his quicksilver guest solo put the snarl into Michael Jackson’s Beat It in 1982. Simply put, his playing was the foundation for shred.

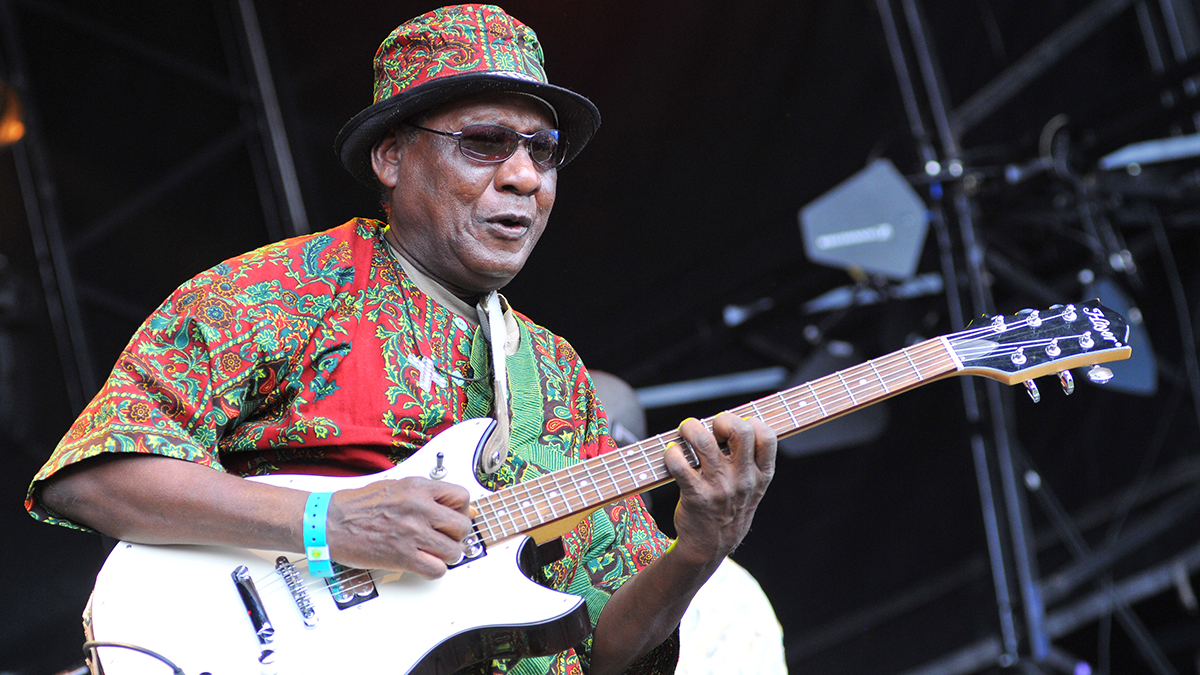

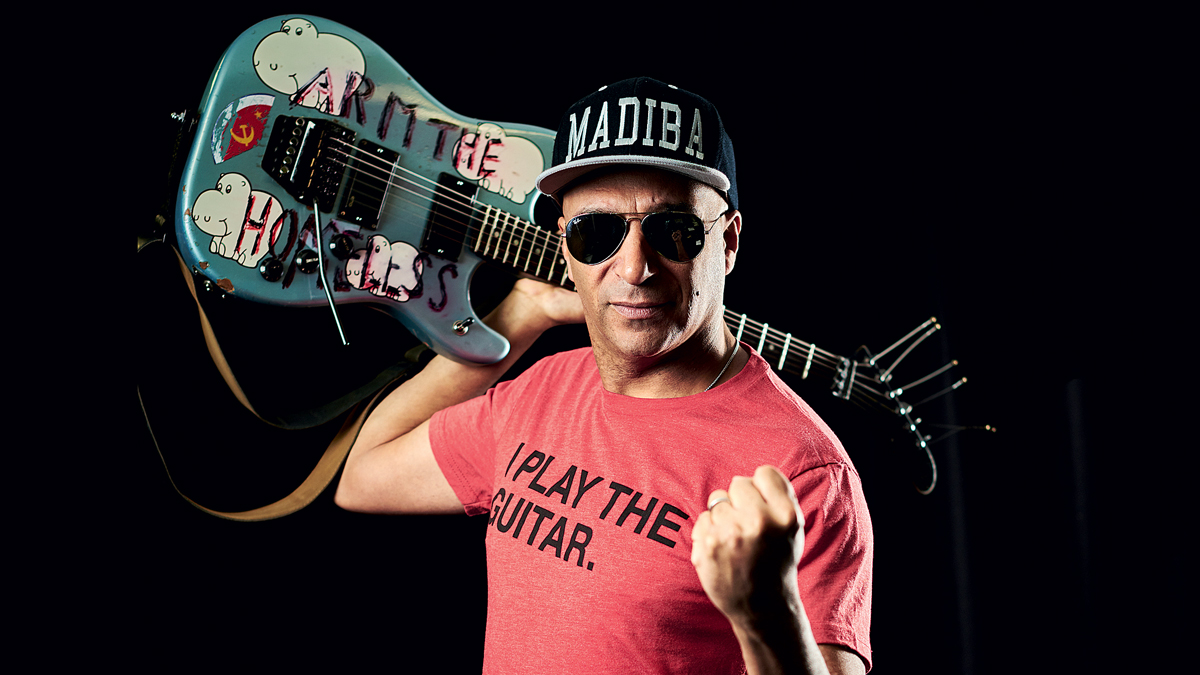

2. Tom Morello

WHAT HE DID: In the Seventies, Jimmy Page was the most influential guitarist in hard rock. In the Eighties, Eddie Van Halen was the most imitated stylist. And in the Nineties, it was Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello who rewrote the Book of Hot Licks.

When Rage Against the Machine formed, I was basically the band’s DJ

Tom Morello

They came out of L.A. at the dawn of the Nineties. The aptly named Rage Against the Machine combined the ghetto anger of hip-hop and the testosterone fury of metal with a keenly felt political mandate to champion the oppressed and fight the abuses of privilege and power.

It was a new and exciting concept back then, and what really drove the point home was the fiercely disruptive guitar work of a Harvard educated young Marxist named Tom Morello.

The napalm cry of exploding bombs, the jagged rhythm of strafing machine guns – Morello wrought seemingly impossible sounds with his ax and became an innovative and radical force in metal.

3. Stevie Ray Vaughan

WHAT HE DID: From the moment his debut, Texas Flood, hit the streets in 1983, Vaughan made the world safe again for old-school blues-based rock while also taking the music he loved into the future.

His impassioned yet highly technical style, which has been often imitated but never duplicated (although Jesse Davey does a damn fine job), altered the perceived parameters of virtuoso guitar playing.

I was gifted with music for a reason, and it wasn’t just to get famous

Stevie Ray Vaughan

When Stevie Ray Vaughan emerged from deep in the heart of Texas waving his battered Strat, it was hardly the best of times for gritty roadhouse rock and blues. The year was 1983 and Vaughan’s debut album, Texas Flood, was released into a musical world that seemed eager to leave its past behind.

Many thought guitars passé, with futurists proclaiming that the venerable instrument would be permanently transformed by MIDI applications and replaced as rock’s dominant instrument by the synthesizer.

Even many guitar loyalists thought the old, classic sounds were no longer adequate, transforming their instruments by running them through racks of elaborate, high-tech gear to create heavily processed sounds. Odd-shaped, brightly colored axes were all the rage. Stevie Ray, on the other hand, was profoundly old-school in almost every respect.

His gear seemed obsolete – just his trusty old Stratocaster, a couple of archaic stomp boxes and a crusty old tube amp.

When he plugged in and started wailing, he was backed only by Double Trouble, his hard-driving, two-man rhythm section of Tommy Shannon and Chris “Whipper” Layton. Their moves weren’t choreographed and they certainly never wore the mascara or sculpted coiffures favored by the burgeoning MTV. They were just three guys playing old-fashioned, rocked-up blues with passion and skill.

A reasonable betting man would have wagered his house that Vaughan would fail to register on the popular culture’s radar screen. But the normal rules of engagement clearly did not apply to this 29-year-old guitar firebrand. Texas Flood blew down the locked, barricaded doors of popular music and proclaimed in no uncertain terms that blues could actually be a potent commercial force.

The album not only quickly put the unknown Texan on the map, but it also signaled that uncompromised, from-the-gut guitar music was not dead as a commercial and artistic force, and that good old Strats and tube amps still had a hell of a lot of life left in them.

4. Slash & Izzy Stradlin (Guns N' Roses)

WHAT THEY DID: Rock music has produced some memorable tandem guitar teams: Keef and Ronnie, Angus and Malcolm, Tipton and Downing. But Slash and Izzy Stradlin, with the original lineup of Guns N’ Roses, surely has to go down as one of the coolest duos ever.

All the other bands in the mid Eighties were trying to have Top 40 hits – even bands like Mötley Crüe. We didn’t care about that. We just wanted to kick some ass

Slash

Guitar rats Slash and Izzy had just enough yin and yang going on to provide color and contrast that made them more than the ordinary lead and rhythm guitar team.

Both loved similar bands, like Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin, but Izzy’s tastes leaned more toward groove-oriented bands like the Rolling Stones and the Doors, with a healthy dose of punk rock thrown in, while Slash loved guitar heroes like Michael Schenker and Jeff Beck.

The combination of Slash’s rough-edged pyrotechnic solos and Izzy’s raw power chords and off-kilter rhythms resulted in an unusual mish-mash with massive crossover appeal that metalheads, punks, glam poseurs, pop fans and classic rockers loved alike.

Slash and Izzy also made vintage guitars cool again, strapping on Gibson Les Pauls, Telecasters and ES-175 hollowbodies when most guitarists were playing DayGlo superstrats, pointy metal weapons or minimalist headstock-less Stein-bortions. Balding guitar players also have Slash and Izzy to thank for making hats fashionable rocker attire during a time when big hair was all the rage.

5. Stanley Jordan

WHAT HE DID: This modern jazz master made a major splash in guitar circles back in the Eighties, in large part because of his innovative “touch” tapping technique and unusual all-fourths tuning. And then there’s that late-Eighties video of him playing Stairway to Heaven on two guitars at once…

I still feel a little limited because it’s not an easy technique. As you’re slamming your fingers into metal, it’s harder on the hands than conventional technique, so I have to make sure I’m relaxed

Stanley Jordan

Simply put, back in the wild Eighties, the Chicago-born, California-raised Stanley Jordan developed a dramatic new way to play the guitar. Jordan’s “touch” technique was – and still is – an advanced form of two-handed tapping that allowed him to play melody and chords simultaneously.

It also became possible, as we’ve hinted above, to play on two different guitars simultaneously. If you love daredevil guitar videos and have access to YouTube in 2020, you might be used to two-handed exploits, but Jordan was doing it in the Eighties (and better).

“I’ve loved classical music ever since I was a kid,” he said in 1987, “and that was the influence – the sound – that I had in mind when I played guitar. I really wanted to hear all that counterpoint, with all kinds of independent lines weaving around each other.”

He’s also said that he’s always on a crusade to promote his technique, the technique is “a means to an end. Having said that, there is something important about the technique as it brings new possibilities.”

Jordan plays in all-fourths tuning, as in EADGCF from bass to treble (all in perfect fourths, as on a bass guitar). The reason? He finds that it simplifies the fretboard, making it more logical.

6. Steve Vai

WHAT HE DID: Since launching his career in the Eighties, Vai has amassed a formidable body of solo work that has made him a demigod of metal and shred, but his virtuosity transcends all such categories.

I’m very honored to be considered an accomplished player. I wear that badge very proudly

Steve Vai

Steve Vai can do things with a sustainer and twang bar that surely ain’t natural and certainly indicate a high tantric mastery of all documented and undocumented alien love secrets. Discovered by Frank Zappa and fostered by David Lee Roth and Whitesnake, Vai emerged in the Nineties as a solo artist and guitar hero of major stature. His astounding technique defies categorization.

In his graceful hands, the guitar becomes a cosmic antenna, channeling other dimensions and parallel universes. His best work combines the swagger of a lifelong rock and roller with the romantic soul of a poet. As if this weren’t enough, he’s also a first-rate composer and has great cheekbones.

His seemingly limitless ability is matched only by his boundless imagination. Unusual scales, complex melodies and rhythms and jaw-dropping speed are all hallmarks of Vai’s approach, while his pioneering development of the seven-string guitar, use of harmonizers and other tone processors, and patented whammy bar-manipulated “talking-guitar” techniques have continually pushed rock playing into new and uncharted waters.

The most important thing to remember when you’re playing modally is what the atmosphere of the mode feels like to you

Steve Vai

Lydian flavors are at the heart of the Vai sound; his song The Riddle, from his 1990 breakthrough album Passion and Warfare, for example, features an excellent example of Lydian soloing.

“The most important thing to remember when you’re playing modally is what the atmosphere of the mode feels like to you. What it sounds like is one thing, but what it feels like – the quality of that mode, that’s when you’re owning that mode. Look at it as an open field. One thing I like to do in Lydian is play every note in the scale except that raised 4th until the last note or close to! That will change the whole atmosphere.”

7. The Edge

WHAT HE DID: For 40 years, his droning, echo-laden guitar tone has been the backbone of U2’s distinctive sound.

I don’t feel that attached to my instruments. It’s almost like I’m going to dominate them in some sort of way. I don’t feel like they’re part of me; they stand between me and something new

The Edge

Few players have done more than U2’s the Edge to define the post-modern guitar style. The Edge – born David Evans in 1961 – showed how textures and rhythms, rather than riffs or chord progressions, could provide the main guitar interest in a song. A master of contrast, he often juxtaposed scratchy rhythms against ringing open chords that resonate with Celtic grandeur.

The Edge exploited the Eighties avalanche of guitar effects to maximum artistic advantage, developing a signature style built on rhythms generated by a digital delay unit and creating a universe of soaring, echoing reverb timbres.

On a series of dizzyingly iconic albums, the Edge created a new language for the instrument, one of harmonic squalls and ringing ostinatos, by turns space-age and rural. Nothing seemed beyond his reach.

Even while jamming with the redoubtable B.B. King on “When Love Comes to Town,” from U2’s 1988 album Rattle and Hum, he was no apprentice, dispensing pure sound (and fewer notes than B.B.) with an exactitude and delight still unsurpassed by any other guitarist.

8. Alex Lifeson

WHAT HE DID: With virtuoso skills and a keen sense of songcraft, Lifeson has been the sole guitar force behind Rush for more than 45 years.

Soloing shouldn’t be about how fast or how many notes you can play… It’s got to really relate to the song or be a reflection of something in your character

Alex Lifeson

In the years since Rush’s 1974 debut album, Alex Lifeson evolved from being a heavy rocker in the classic Seventies power chord/pentatonic scale tradition to his role as rock’s preeminent texturalist that lasted well into the 2000s.

As Rush’s compositional sophistication grew in the late Seventies and Eighties, so did Lifeson’s guitar work – his favored use of suspended chords (played with plenty of chorus and delay) instead of triads defined the ethereal, instantly recognizable and often-imitated Rush sound.

Lifeson developed his signature sound by using arpeggios as harmonic pads underneath Geddy Lee’s vocals to counterbalance the band’s driving, odd-metered riffs.

Other Lifeson stylistic approaches include using notes on the top strings as common tones above a moving arpeggiated bass line (Fly by Night), incorporating open strings in arpeggiated sequences (Closer to the Heart) and sustaining open strings over moving power chord shapes (Jacob’s Ladder).

9. Kurt Cobain

WHAT HE DID: He was the premier icon of grunge, the raw, guitar-heavy, blunt-spoken style that will stand for all time as a signifier of the Nineties.

I wouldn’t have been surprised if they had voted me Most Likely to Kill Everyone at a High School Dance

Kurt Cobain

Although it is tempting to imagine Kurt Cobain as just a symbol of alterna-rock angst, the power and ingenuity of his actual playing proves that there was more than “teen spirit” at work in his music. The Nirvana frontman grew up in Aberdeen, Washington, where his initial points of reference were hard rock staples like AC/DC, Led Zeppelin, Kiss and Cheap Trick. In 1980, he discovered punk, and his musical course was set.

Never a technical player, Cobain rarely relied on flash, preferring to make his point through dynamics instead, fleshing out his songs with judicious use of distortion and feedback.

Even his “solos” tended to be self-effacing in the extreme; the guitar break in Teen Spirit, for example, merely reprised the vocal line. But Cobain’s deft use of harmony and lean, tuneful sense of line more than made up for any lack of chops, shoring up the songs so exquisitely that it was easy to overlook how elegant his playing was.

10. Emily Remler

WHAT SHE DID: Pardon the cliché, but Emily Remler, a young guitarist from Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey (the same town where Rudy Van Gelder helmed scores of classic jazz albums in the Fifties and Sixties) took the jazz world by storm from the late Seventies until her death in 1990. No less a jazz giant than Herb Ellis once called her “the new superstar of guitar.”

I may look like a nice Jewish girl from New Jersey, but inside I’m a 50-year-old, heavy-set black man with a big thumb, like Wes Montgomery

Emily Remler

Things took off for the 21-year-old Remler when Herb Ellis got her an engagement at California’s Concord Jazz Festival on a bill called “Guitar Explosion” that also featured jazz legends Barney Kessel and Tal Farlow.

Once that happened, there was pretty much no stopping her; in fact, Remler, who had a notably loose, laid back but hard-swinging playing style, tended to outshine and outplay a goodly portion of the other – more established – guitarists with whom she shared future bills.

She even won Guitarist of the Year in Down Beat magazine’s 1985 international poll. By the late Eighties, Remler was experimenting with guitar synth and Brazilian and African rhythms.

Remler died of heart failure in 1990 at age 32. Since then, several peers and admirers have written and recorded tributes to her, including Just Friends: A Gathering in Tribute to Emily Remler, Volume 1 [1990] and Volume 2 [1991]. Skip Heller even wrote a song called “Emily Remler” in her memory.

As a teenager, Jeff Kitts began his career in the mid ’80s as editor of an underground heavy metal fanzine in the bedroom of his parents’ house. From there he went on to write for countless rock and metal magazines around the world – including Circus, Hit Parader, Metal Maniacs, Rock Power and others – and in 1992 began working as an assistant editor at Guitar World. During his 27 years at Guitar World, Jeff served in multiple editorial capacities, including managing editor and executive editor before finally departing as editorial director in 2018. Jeff has authored several books and continues to write for Guitar World and other publications and teaches English full time in New Jersey. His first (and still favorite) guitar was a black Ibanez RG550.