All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Most guitarists rarely give potentiometers a second thought, but they dramatically affect an instrument’s tone and feel, and changing them can be a very cost-effective upgrade. This issue, we’re telling you everything you need to know about pots, starting with an explanation of how potentiometers work in electric guitars.

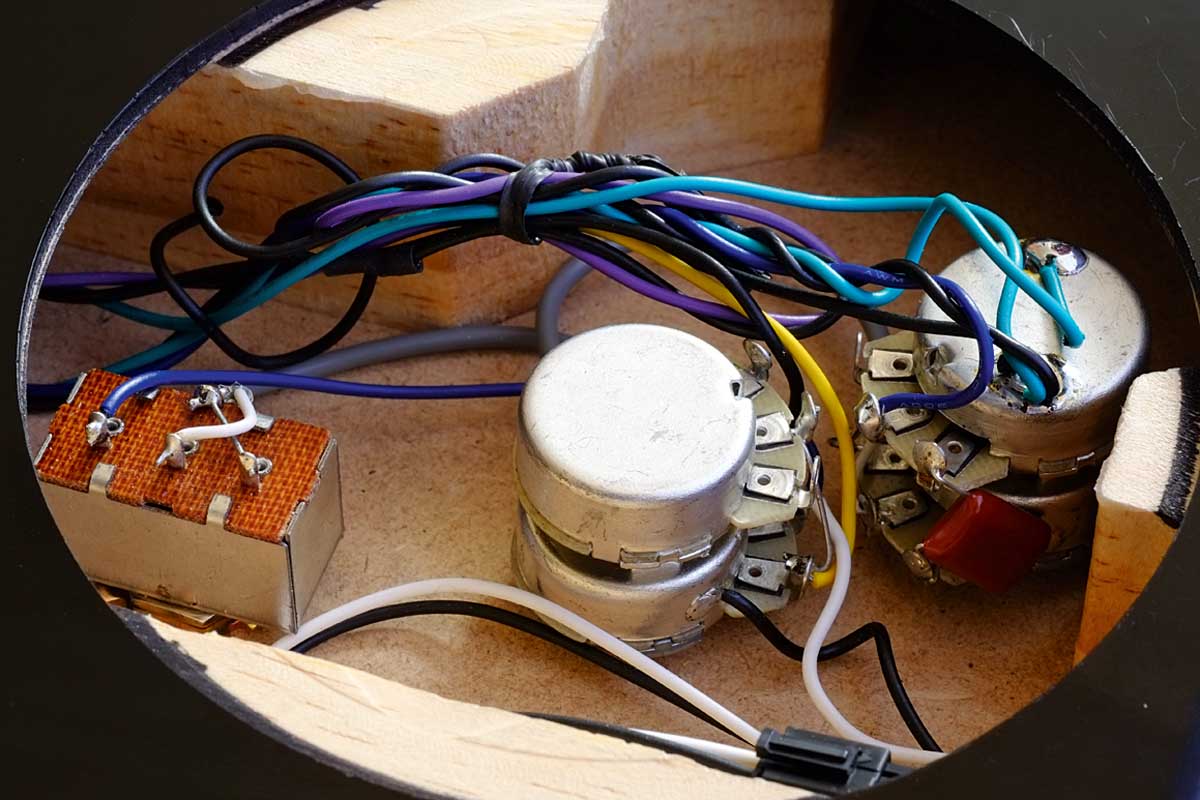

Potentiometers have three solder tags and the outer ones are connected via a conductive strip that has a preset resistance. The centre tag (tag 2) connects to a ‘wiper’, which tracks along the conductive strip when you turn a control knob. For volume control, tag 1 is connected to the pickup positive or selector switch output, tag 2 goes to the output socket, and tag 3 is grounded.

If the wiper is turned fully in one direction, there will be no resistance between tags 1 and 2, and maximum signal level appears at the output socket. Turned fully in the other direction, there will be no resistance between tags 2 and 3, and there will be no output because all the signal goes to ground. Anywhere in between, there will be some resistance between the wiper and both the outer tags.

When the resistance between the wiper and tag 1 is lower than the resistance between the wiper and tag 3, a greater proportion of the pickup signal will be routed to the output. But if the resistance is lower between the wiper and tag 3, more of the pickup signal will go to ground and the output level is reduced. The potentiometer functions as a variable ‘voltage divider’.

For tone control, only the wiper and one of the outer tags are used. The third tag remains unconnected and may be removed. Tone capacitors can be connected between the volume and tone pots, or between one of the tone pot’s tags and ground.

In both cases, it is the potentiometer that determines how much of the high-frequency content passing through the capacitor reaches ground. The pot operates as a variable resistor and tone is at its darkest when there is zero resistance between the two solder tags.

Value Added Tone

The most commonly used pot values are 250kohms and 500k for most Fenders and Gibsons respectively. Jazzmasters, Jaguars and some Telecasters have 1meg-ohm pots, while the very earliest 1954 Stratocasters had 100k pots. With Gibson instruments, there’s an element of ‘pot luck’ because many have 300k pots.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

If you’ve tried loads of different pickups in your Gibson, but it continues to sound dull, then you should confirm the pot values are 500k – otherwise pickup swaps will continue to disappoint.

Guitar manufacturers select pot values to achieve their preferred treble response. Humbucker and P-90-style pickups are usually paired with 500k pots, whereas 250k versions help to prevent brighter single coils sounding shrill.

Electric guitar pickups are resistive, inductive and capacitive, and they never have a perfectly flat frequency response. Instead, they generally exhibit a very strong resonance peak, with a rapid roll-off above the resonance frequency. The amplitude and frequency of the peak strongly influence the sonic character of a pickup.

A volume potentiometer is effectively a resistor connected in parallel with the pickup. This resistive ‘load’ on the pickup reduces the resonance peak, and the lower the pot value, the lower the peak. This is why the same pickup will seem less trebly with a 250k pot than with a 500k or 1meg-ohm.

But rather than rolling off the treble, lower value pots actually make the frequency response more linear. This also partly explains why a guitar will appear to lose treble when its volume control is turned down.

Experiment with pot values to discover which you prefer, but be aware that a pot’s stated value will always be nominal and there will be some variation above and below. You can measure a pot’s true value by setting a multimeter to resistance mode and placing the probes on the outer solder tags.

Pots in vintage Gibsons frequently measure way north of 500k and can be closer to 600k. When combined with naturally bright unpotted P-90s and PAFs, they contribute to the clarity, bite and definition of those guitars. If you want something remarkably similar, check out Bare Knuckle’s 550k pots.

Taper Talk

A pot’s taper determines the way it responds. If your multimeter reads 0 ohms between the input tag and wiper at one extreme, 500k at the other, and 250k at half way, the pot is a 500k with a linear taper. There should be a ‘B’ prefix adjacent to the pot value on the casing.

When resistance increases slowly, reads less than 250k in the middle, and then increases rapidly towards 500k, then what you have is a 500k pot with a logarithmic taper, and an ‘A’ prefix should indicate this. These are also called ‘audio taper’ or ‘log’ pots. Beware that audio tapers vary substantially and the taper, which is usually expressed as a percentage, affects a pot’s feel and useful operating range.

Our ears don’t perceive volume changes in a linear way, however, so log pots actually sound smoother and more ‘linear’ than linear pots. Consequently, log pots are generally preferred for volume and tone control applications. However, if you prefer tone controls with a quicker response for wah-type effects, then try a linear pot.

The vogue for drilling switch holes in pickguards and guitar bodies is long over. Besides the fact it devalued instruments, switching pots can now provide all those series, parallel, phase and coil-tap tone options without any need for irreversible modifications

Onto visuals, and the codes stamped on the outer casing can be used to identify the company that built the pot and also provide some indication of when the guitar itself was built. In instances where the serial number has been sanded off or overpainted, the pot codes may be the only thing to go on when you’re trying to date a vintage guitar.

Sometimes you have to start with pot codes and assess whether the guitar’s other features are consistent with those dates. Unfortunately, codes are often obscured by solder blobs. If you want more detailed information on this, many websites provide the codes along with pot code ‘de-coders’.

The vogue for drilling switch holes in pickguards and guitar bodies is long over. Besides the fact it devalued instruments, switching pots can now provide all those series, parallel, phase and coil-tap tone options without any need for irreversible modifications to precious instruments.

Switching pots work just like regular pots, but the shaft moves in and out to activate a switching section that’s attached to the rear of the pot casing. Push-pull pots are the most common, and the switch is operated by pulling up and pushing down on a control knob.

While this works well with some knobs, tapered Strat and Les Paul knobs can be hard to grip when you need to pull them up in a hurry. In that case, you may find that a push-push switch is preferable because tapping the top of the knob activates and deactivates the switch.

Fender’s S-1 switch is another option, albeit an expensive one. The S-1 must be used with special Strat and Tele knobs that have an independent central section, which pushes in to operate the switch.

Double Check

Potentiometers are sometimes doubled up and they come in two varieties: dual-gang and dual-concentric. Both are stacked potentiometers, but dual-gang pots are operated by a single shaft, while dual-concentric potentiometers operate independently.

It’s more common to see dual-concentrics used for instruments, including various Danelectro models and Fenders such as the Jazz Bass, Nashville Power Tele and Acoustasonic Tele.

If you’re handy with a soldering iron, try disconnecting the tone control and you’ll notice your guitar has more treble and clarity – and it may sound a bit louder, too

You’ll need special knobs to use with dual-concentrics, since one knob controls tone and the other volume. Consider these if you need to cram numerous controls into a limited space.

Dual-gang pots are more commonly seen in pedals than guitars, but they can be used in pickup blender/balance applications. During the early 1950s, Gretsch used dual-gang pots for tone control. Providing treble cut in one direction and bass cut in the other, these controls should be set around halfway for regular playing. If you’ve ever played an early 50s Gretsch and found it too bright and thin, that might explain why.

Having tone controls guarantees some degree of treble loss, even when the control is set to 10. Whatever the pot value, there is always a path for frequencies passing through the tone capacitor to reach ground.

If you’re handy with a soldering iron, try disconnecting the tone control and you’ll notice your guitar has more treble and clarity – and it may sound a bit louder, too. It’s the main reason the back position on a Fender Esquire differs from a regular Tele, and Gretsches with (inactive) mud switches sound twangier than those with conventional tone controls.

If you like that extra treble but still want to use a tone control, consider replacing your tone pot with a no-load potentiometer. In no-load pots, the resistance strip stops a tad short. When the control is set to 10, the wiper is out of circuit and there’s no path for the treble frequencies to reach ground.

Pot Noodling

If you feel inspired to upgrade your potentiometers or try some different values or tapers, there are a few things to consider. Guitars with push-on control knobs – such as Strats and all Gibsons – require split-shaft knobs.

Guitars with knobs that are held in place with a little grub screw need solid-shaft pots. If you can only get a split-shaft but need a solid-shaft, Allparts UK supplies brass sleeves that slip over split-shafts to convert them to pseudo solid-shafts.

Pots also come with long and short shafts. Guitars with arched tops may have pot holes that are relatively deep, so you’ll need a long shaft. For most applications, short shafts are fine, but check before ordering. And if your guitar is of Asian manufacture, the pot holes may need to be widened for US-spec pots.

Finally, an important thing to note for any southpaws among you: if you’re left-handed then you’ll need to buy ‘left-handed’ potentiometers, otherwise all your controls will work backwards!

Huw started out in recording studios, working as a sound engineer and producer for David Bowie, Primal Scream, Ian Dury, Fad Gadget, My Bloody Valentine, Cardinal Black and many others. His book, Recording Guitar & Bass, was published in 2002 and a freelance career in journalism soon followed. He has written reviews, interviews, workshop and technical articles for Guitarist, Guitar Magazine, Guitar Player, Acoustic Magazine, Guitar Buyer and Music Tech. He has also contributed to several books, including The Tube Amp Book by Aspen Pittman. Huw builds and maintains guitars and amplifiers for clients, and specializes in vintage restoration. He provides consultancy services for equipment manufacturers and can, occasionally, be lured back into the studio.