Radiohead's 'The Bends,' 20 Years Later: Reexamining a Modern Rock Masterpiece

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was the late winter of 1995, and Kurt Cobain had been dead for almost a year.

American alternative rock was caught in a grunge hangover; top acts of the time included Pearl Jam, the Smashing Pumpkins, and Dave Grohl’s new project the Foo Fighters.

In the U.K., a few bands such as Bush were attempting to cash in on the post-Nirvana craze for big distorted guitar riffs and feral howling, but the real chart conquerors were Oasis, Blur and their counterparts in the fun but mostly backward-glancing Britpop movement.

Meanwhile, on both sides of the Atlantic, thanks to the likes of Moby, the Prodigy and Massive Attack, electronic music was beginning to seep into the mainstream. With all this going on, it’s fair to say that most band watchers didn’t expect much from Radiohead.

Sure, the young quintet from England’s Thames Valley had lucked into a hit two years earlier. A big one, too: “Creep,” a melodramatic anthem of self-loathing marked by singer Thom Yorke’s surprising emotional range—first moping, then soaring—and a memorable guitar hook (played by curtain-haired Jonny Greenwood) that sounded like a shotgun being loaded.

But their subsequent singles hadn’t performed anywhere near as well. Neither fish nor flesh, Radiohead didn’t fit in with the Britpoppers and weren’t grungy enough to be grunge. Music industry folks were already writing them off as a one-hit wonder.

Then, on March 13, Radiohead’s second album, The Bends, was released. From its very first few seconds—the Roland Space Echo whooshes, reverberating piano chords, and crashing drums that open “Planet Telex”—the message was clear: We’re not the people you thought we were, and we’re about to make a major statement.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Forty-eight astonishing minutes later, Radiohead had done just that, serving notice to the world that their talent, ambition, and ability to execute were far greater than just about anyone had imagined. From the uneasy slow-build balladry of “Fake Plastic Trees” to the dizzyingly complex three-guitar arrangement of “Just” and the plaintive, heart-piercing chorus of “Street Spirit (Fade Out),” The Bends was a modern rock tour de force.

Although it took a while to catch on commercially—its biggest sales figures weren’t achieved until nearly a year after it came out—The Bends won critical acclaim from the start. (I was so taken with it that I eventually wrote a book on the band.) And that acclaim has only grown over the years.

The Bends now routinely takes high spots on critics’ and music fans’ lists of the best rock albums of the Nineties, or the past two decades, or ever. A 2006 readers’ poll in the British music magazine Q placed it at No. 2 all-time (No. 1 was Radiohead’s follow-up disc, 1997’s OK Computer). More important, the album’s influence on other musicians has been both wide and deep. Nearly every arty, big-sounding band of recent vintage owes something to Radiohead’s example; just follow the lines from Coldplay to Arcade Fire to Mumford & Sons.

But at the time The Bends was released, influencing others wasn’t exactly foremost in the minds of Radiohead’s members. Their prime concern was to establish a lasting career, and to escape the pigeonhole they’d been stuffed in by the success of “Creep.” In their early music, they’d moved with the alternative tide, referencing the work of Eighties juggernauts like U2, R.E.M., the Pixies and the Smiths. Now they were thinking bigger, and looking further back: to the high drama of Queen, Pink Floyd and the psychedelic-era Beatles.

And so it was entirely appropriate that the band chose John Leckie as the producer for their second album.

First hired by Abbey Road Studios as a tape operator in 1970, Leckie had cut his teeth working on John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band, George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, and Pink Floyd’s Meddle. Since then, he’d produced many other Radiohead favorites, including Simple Minds, XTC and Magazine.

Radiohead’s label, EMI, booked nine straight weeks with Leckie at RAK studios in North London, beginning in February ’94. Band and producer got along famously: “The best part about working with John Leckie,” Greenwood later recalled, “was that he didn’t dictate anything to us. He allowed us to figure out what we wanted to do ourselves.”

Unfortunately, the RAK sessions soon turned tense. Word from the label was that the band should concentrate on producing a leadoff single first, but no one could agree on what that single ought to be, so they tried four single contenders in succession: “Sulk,” “The Bends,” “Nice Dream” and “Just.” None of them felt right. The constant search for some magic hit sound slowed the recording process to a crawl. “I couldn’t have been more freaked out,” Yorke remembered. “We had days of painful self-analysis, a total fucking meltdown for two fucking months.”

The turnaround finally came in April, when Leckie suggested that Thom try playing “Fake Plastic Trees” by himself. There was nothing to lose; all previous attempts by the full band to capture this anti–power ballad on tape had failed. “There was one stage…when it sounded like Guns N’ Roses’ ‘November Rain,’ ” guitarist Ed O’Brien reported. “It was so pompous and bombastic, just the worst.” But this time, alone with his acoustic guitar, Thom was finally pleased with the results. It was this solo performance that Leckie and the rest of the band used as their foundation to build the final track.

With that song and several others in the can—and the original October deadline for the album put aside for good—Radiohead took to the road, playing a series of shows in Europe, the U.K., Japan, and Australasia through May and June. They took the opportunity to air much of the material they’d been working on at RAK.

One gig, at the Astoria in London on May 27, was filmed by MTV Europe and recorded by Leckie. That was a smart move, because the band’s fiery live take of “My Iron Lung,” another song they’d labored in vain to get right in the studio, ended up winning approval from all concerned. The band liked it so much, in fact, that it became the first Bends-era song to see the light of day, as the leadoff track of an EP released in September (the other six songs on that EP were cut at RAK but rejected for the final album).

At the time, “My Iron Lung” was greeted with some puzzlement by fans and critics alike. Its transitions from jangly, ring-modulated opening hook to McCartney-esque verse melody to pulverizing guitar explosions in the bridge were jarring and didn’t correspond to what anyone expected from Radiohead. But now, placed next to its 11 fellow songs on The Bends, it makes much more sense. And except for Yorke’s lead vocal, which was replaced later, what you hear on the final recording is exactly what was played on the Astoria stage that night in May ’94.

From here, the going got easier. The weeks spent playing live had loosened Radiohead up, and they completed The Bends in bits and pieces over the next several months at the Manor in Oxfordshire and Abbey Road in London. Songs like “Bones,” “Sulk” and the album’s title track, which had caused no end of problems earlier in the year, were set down with a minimum of fuss.

“When we finished The Bends,” Yorke said, “it felt like going back and doing four-tracks again. That’s what was so exciting—that we were in control of it, that it was our thing. We were simply satisfying ourselves.”

Still, EMI remained uncertain about the album’s commercial prospects and didn’t want to take any unnecessary chances. Once recording was finally concluded in November, the label asked both Leckie and the American team of Sean Slade and Paul Q. Kolderie, who’d produced Radiohead’s debut album Pablo Honey, to mix it. In the end, three Leckie mixes and nine Slade/Kolderie mixes made the cut.

Considering all the drama that had been generated during recording and mixing, it was interesting, and a little amusing, that one song in the album’s final running order—“High and Dry,” also released as a single—actually predated the RAK sessions by almost a year, having been recorded in ’93 at Courtyard Studios just outside Oxford by the band’s live sound engineer Jim Warren.

Among the most striking aspects of the new material was that it found Radiohead expertly exploiting one of their most unusual traits: the fact that they were a three-guitar band (with O’Brien, their tallest member, joining Yorke and Greenwood on six-string duty).

On Pablo Honey, their general tendency had been simply to lay one more or less identical guitar part on top of another and another, forming a dense, fuzzy wall. For The Bends, they took a completely different approach, creating a sensible division of labor. In general, Yorke handled the chords, Greenwood did the fancy lead playing, and O’Brien was in charge of the unusual effects, but this could vary from song to song—or second to second. And for the first time, no one was afraid not to play.

In O’Brien’s words, “we were very aware of something on The Bends that we weren’t aware of on Pablo Honey…if it sounded really great with Thom playing acoustic with [drummer] Phil [Selway] and Coz [bassist Colin Greenwood], what was the point in trying to add something more?” Yorke added, “Sometimes the nicest thing to do with a guitar is just look at it.”

One other thing that set The Bends apart from Radiohead’s previous work was the greater amount of group contribution to the songwriting. Though Radiohead’s songs have always been credited to the whole band, most of the early ones were mainly by Yorke.

This changed during The Bends. “Nice Dream,” for example, was originally a simple four-chord Yorke composition, but Greenwood and O’Brien added more parts, including the intro. And the music to “Just” was largely written by Greenwood, who Yorke said “was trying to get as many chords as he could into a song. It was like writing a medley.” Because Jonny is the most musically knowledgeable member of the band (trained as a classical violist, he has since carved out a distinguished side career as a composer), it’s not entirely surprising that he’d be interested in showing off this way.

Sure enough, the progression of “Just” is full of jagged chromatic twists, and Greenwood lays an octatonic diminished scale ascending through two octaves over the chorus, adding to the feeling of menace. Other guitaristic high points of the song include a cool, clean two-part harmony section (played by Thom and Jonny) and Greenwood’s closing solo, affectionately referred to by some as the “bwena-bwaaa” part because of the strikingly vocal quality of his vicious bends.

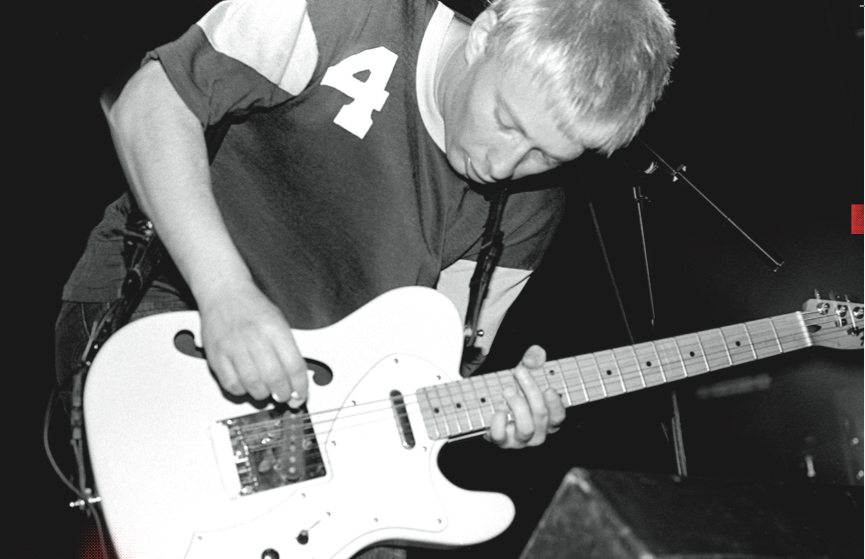

Interesting historical note: On this track and throughout the sessions for The Bends, Jonny used two 1990 Fender Telecaster Plus models exclusively, one with a Tobacco Burst finish, the other in Ebony Frost. These guitars were stolen while the band were in Denver for an October ’95 concert.

Last year, a fan browsing a Radiohead gear site saw a description of the ebony Tele and realized he owned it, having bought it in Denver in the mid-Nineties. Messages were exchanged, arrangements were made, and nearly two decades after the theft, Greenwood was reunited with his Tele—which he took back onstage for the first time this past February, performing Steve Reich’s “Electric Counterpoint” with the London Contemporary Orchestra in his hometown of Oxford.

Upon its March ’95 release, The Bends was hailed by critics worldwide as a masterpiece. “Radiohead have suddenly bloomed into one of this country’s most magnificent bands,” the London Times proclaimed. Setting the tone for the band’s future work, Yorke’s lyrics are pretty grim throughout the album, a veritable compendium of disease, disgust and depression.

To pick just one example (from “Street Spirit”): “Cracked eggs, dead birds/Scream as they fight for life/I can feel death/Can see its beady eyes.” And yet the melodies to which these lyrics are set are so inviting, their arrangements so creative, and the group playing so powerful, that the overall effect is uplifting.

Radiohead supported The Bends with relentless gigging. They toured the U.S. alone six times within a year and a half, including a stint opening for new pals R.E.M. The hard work paid off, as the album slowly crept toward Gold (500,000) and then Platinum (one million) sales status in America. Even so, it never got any higher on the Billboard charts than No. 88, which to this day remains the worst U.S. chart placing for any Radiohead album.

In the middle of all this live activity, on September 4, 1995, with The Bends’ principal engineer Nigel Godrich at the controls, the band recorded a slow, grand, highly Pink Floyd–ian number called “Lucky” for a charity compilation album.

O’Brien opens the song by strumming the strings of his ’86 Squier Strat above the nut, creating a kind of sonic halo over Selway’s beat that perfectly establishes the ghostly mood. (Like Jonny’s ebony Tele, Ed’s Strat would be stolen in Denver a month after this recording session; unlike the Tele, it’s never been recovered.) The “Lucky” session took only five hours to complete, including mixing, and all concerned regarded it as one of their finest moments. “ ‘Lucky’ was indicative of what we wanted to do,” Yorke told me after the fact. “It was like the first mark on the wall.”

The song would reappear two years later on OK Computer, the album that made Radiohead global stars. But just as they resisted being pigeonholed after “Creep,” so too would they quickly veer away from the guitar-focused art-rock atmospherics of OK Computer.

Further groundbreaking music lay ahead: Kid A, Amnesiac, Hail to the Thief, In Rainbows, The King of Limbs.

Today, nearly 25 years into their professional career, Radiohead have the same five members they started with, but they continue to grow and change stylistically. And the more wildly they experiment with their sound, the more popular they seem to become.

Their journey together is of a rare and inspiring sort, and The Bends was that journey’s crucial turning point.