Marty Stuart: “It started with my Clarence White Telecaster. That old guitar is kinda like an invisible band member. It has a tone of its own”

The country legend on channeling the Byrds’ guitar tones, how YouTube helps him cope with the loss of Johnny Cash and finding the amp he’d been searching for all his life

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

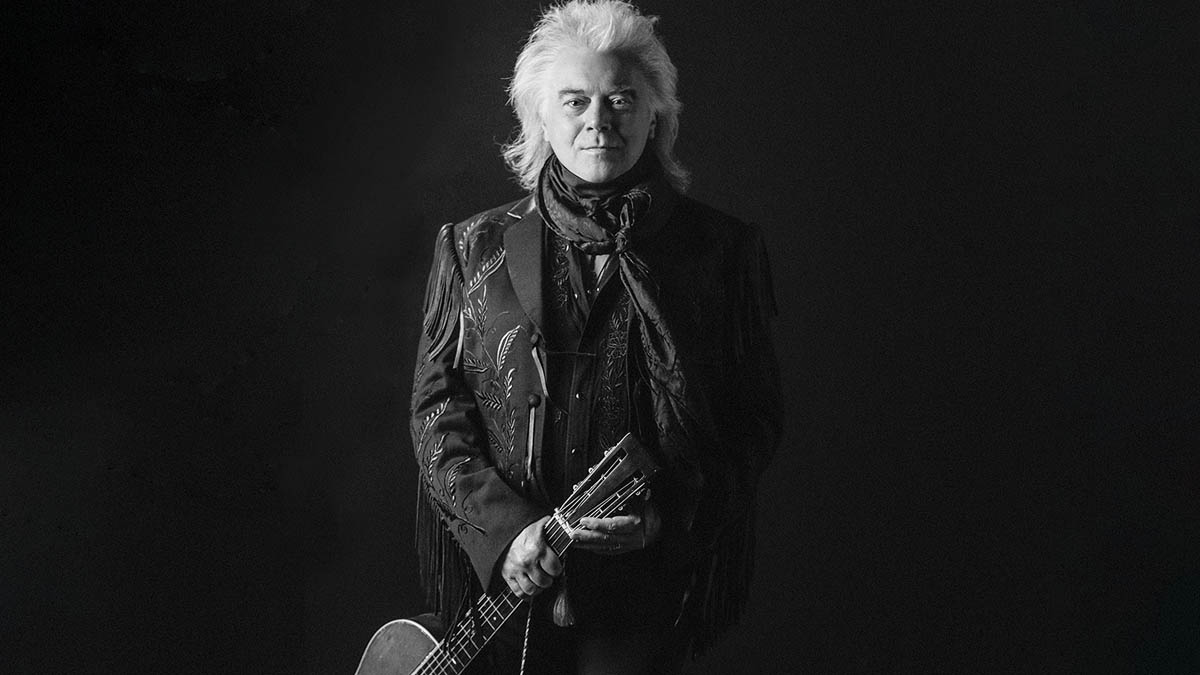

For the rock journalist, there is no greater joy than a musician living up to their mythology. As the Zoom call connects, the Marty Stuart of our mind’s eye is suddenly sat opposite us in a Memphis dressing room.

Soundcheck might be an hour away, but the famously dapper country star already looks the part. Black scarf. Black jacket. Black hat. Black everything, in fact, except the stray silver hair that speaks of his 64 trips around the sun.

A slightly evaluating look on his face, perhaps, while he waits a moment to establish if we’re an idiot or not. But then a palpable thaw, as Stuart relaxes into his witty and generous interview manner, never far from an anecdote or rumbling chuckle.

And what anecdotes he has at his disposal. Stuart is fascinating company for his solo career alone, which got motoring in the late ’80s when he signed to MCA and reignites this year after a half-decade silence with the excellent Altitude.

But it’s worth reminding yourself, too, that this man cut his teeth with bluegrass giant Lester Flatt, held his own in Johnny Cash’s road band, recently toured with the remnants of The Byrds and still owns the heavily modded Telecaster first owned by that band’s fallen legend, Clarence White. Let’s start with the here-and-now.

Do you still enjoy the road?

“I love the road. It’s my office. I love the applause. I love the smell of diesel fuel. I love the bad food, whatever. I’m a road dog.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It’s six years since Way Out West. How has that time been for you?

“I hadn’t had a year off since about 1972, so I enjoyed being at home with Connie [Smith, wife and country musician]. And the band probably needed a rest. Because after Way Out West, all of a sudden, people came calling. We played 60-something shows with Chris Stapleton, 30-something with The Byrds, 40 or 50 with Steve Miller. So we were scrambling. I knew that Way Out West was just the beginning of something I wanted to tie back into with Altitude.”

Are you pleased with Altitude?

“I’m very happy with it. We had that record so ready to go, and then here comes the pandemic and they close Capitol Studios. I thought, ‘If we don’t record this record right now, we’re gonna lose the whole feel. It’ll be a different record.’ So we put on masks and went to East Iris Studios. The end result, I think, is pretty honest. But that recording session was a new one on me. I hope we never have to do that again.”

The guitars on Altitude have both jangle and twang – what prompted that?

“Well, it started with my Clarence White Telecaster. That old guitar is kinda like an invisible band member. It has a tone of its own. So we kinda centred the record around that. And we had just come off tour with Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman – we got to be The Byrds!

“It was like kids in a candy store. So the sound of my Clarence guitar and Roger’s 12-string and Chris’s bass was all in my head and I wanted to carry some of that with me into the studio for Altitude. So that’s what happened. This record just felt like another chapter in cosmic cowboy desert land [laughs].”

The album starts with a Byrdsian instrumental called Lost Byrd Space Train – is that your tip of the hat to those guys?

“The latter version of The Byrds would sometimes do Eight Miles High. Sometimes, it was unbearable, it was so long. It was really jam-bandy, but on the right night, there was magic in there. So that’s where that idea came from. Like I said, I just wanted it to sound like we’d wandered in out of the darkness wearing Clarence’s guitar.”

Do you look inward or outward as a songwriter these days?

“Both. I had a conversation one time with Pete Seeger. And I had to ask him about Woody Guthrie. Pete had a great observation. He said Woody was like a travelling correspondent on a boxcar, looking left and right as he travelled, taking in the human condition, then reporting on it.

“I thought that was one of the greatest job descriptions of a songwriter I’d ever heard. Merle Haggard was another. You or I could look at a glass of water and we’d see one thing. Merle could always see that glass of water from a different angle. And I think, any time you can come within a mile of those kind of observations, whatever you’re writing about, it’s a good thing. And I love words.”

Connie almost died of Covid. Two-and-a-half years later, she is just now rising to the level where she sounds like her singing again

As a writer, it seems like you still empathise with the man on the street.

“Absolutely. Going back to Woody Guthrie, it’s about looking around. And especially at the time we were making this record, that song Time To Dance – it’s probably not my favourite song on the record, but it’s something that I needed to say to myself at the time. Because we can lose hope.

“Connie almost died of Covid. Two-and-a-half years later, she is just now rising to the level where she sounds like her singing again. It’s like the girl I married is back in the house and it’s not this whole physical drudgery every day. So one day, I said to myself, ‘Well, there’s a back door to this pandemic somewhere, and we will all dance again.’ Well, there’s your song, Marty.”

The Clarence Telecaster is always non-negotiable. How about your guitar amp choice for this record?

“I rented a 70s ‘Silverface’ Deluxe, maybe nine years ago, from SIR [Studio Instrument Rentals] in LA. And the minute I plugged into that amp, I thought, ‘I been looking for you all my life.’ You know the rule at SIR: they don’t sell. I appealed to the guy, and I don’t know how much money I laid on the table, but I would have laid twice as much to have it. He gracefully sold it to me.

“There’s a guy in Hollywood – Andy Arahood – and he hot-rodded it. Now it growls, like there’s a tiger in that amp. I use it on stage, in the studio. It’s a one-stop-shop kinda amp. Live, on the song Time Don’t Wait, there’s a Radial [BigShot] PB1 Class-A [Power] Booster for the solo and the outro. And that’s about it for pedals.”

How do your band, The Fabulous Superlatives – Kenny Vaughan, Harry Stinson and Chris Scruggs – push you as a musician?

“First of all, they’re the first group I’ve ever been a part of where it doesn’t matter what style I’m interested in, they’ll just say, ‘Okay, let’s do it.’ Their vocabulary and range is just impeccable. And it’s a luxury. I’m spoilt rotten for having such a band around me. But we push each other.

“And the beautiful part – which I wish you could see – is when we’re writing and working up a song. There’s very little said. It’s just understood and it happens. I remember the first time working with Kenny [Vaughan, guitarist] in the studio. I took all the faders down except for his guitar and my guitar. It was like the most beautiful dance. We never stepped on each other. It was like a tapestry.”

Kenny plays everything. He’s also a pretty deadly session musician with a unique, quirky and profound arsenal of guitars

Kenny is a Telecaster man too, right?

“Well, Kenny plays everything. He’s also a pretty deadly session musician with a unique, quirky and profound arsenal of guitars. Out here he’s pretty well a Telecaster player, but I really love it on the song Tomahawk when he plays the Stratosphere guitar [a custom RS Guitarworks doubleneck]. Back in the ’50s, Jimmy Bryant had a song called Stratosphere Boogie, and he and his buddies created this strange tuning that Kenny and [Fabulous Superlatives bassist] Chris Scruggs figured out.

“On Tomahawk, Kenny plays that tuning on the Stratosphere guitar and the sun comes out when I hear it. It’s a hard tuning to reckon with [the six pairs of strings on a 12-string guitar are tuned low to high: AF CA FD AF CA EC]. But Kenny mastered it. And it’s just absolutely awesome.”

You’ve been based in Nashville for 50 years now. Do you remember your first night in town?

“Without question. It was two in the morning. Roland White forgot to pick me up and I was standing out there by myself in the middle of dirty, seedy Nashville. Scary, at that time. I walked around to the side of the Greyhound bus station and there was the Ryman Auditorium. And it almost made me cry because that was the place I wanted to go. In some ways, that feels like a million years ago. In some ways it feels like it was last night.”

Has Nashville still got the soul?

“If you know where to look for it. The face value of everything in Nashville has changed. Very few people are left that were part of that cast when I first got to town. The labels have changed. The business of country music has changed. Some of the buildings remain. But if you know where to look, there’s still a heart and soul there.”

I knew the history of country music. I knew who had been there. I knew that Johnny Cash had got kicked off of that show for tearing up the footlights with his microphone stand

How did it feel to get on the boards of the Ryman?

“I couldn’t believe it. I knew the history of country music. I knew who had been there. I knew that Johnny Cash had got kicked off of that show for tearing up the footlights with his microphone stand. I knew there was a moment of silence the weekend after Patsy Cline died in a plane crash.

“So I felt like I was a part of that family before I ever set foot in the building. I knew the weight of the place. I didn’t know that I was going to be a permanent member of Lester Flatt’s band – I just thought I was going to be a guest the first time I played. But it worked out.”

Do you still think about Johnny Cash?

“All the time. There’s not a day goes by I don’t miss him. I miss his wisdom and I truly miss his sense of humour. I miss picking up the phone and knowing that I could always hear the truth or at least something good on the other end of that line. But the good news is that he’s everywhere. So when I miss him very much, I can find him on YouTube or play his guitars or look at his lyrics and his costumes. I have all that stuff.”

Jimmie Rodgers laid it down: country's about trains, gamblin’, ramblin’, cheatin’, hoboin’, sin, redemption, jail, mothers, home, dying, bills

You’ve been operating a country music memorabilia exhibit at the Two Mississippi Museums. What are the best Cash guitars on display?

“I have a 1939 D-45 that belonged to Hank Williams, that Hank Jr gave to John – and John gave to me. I have his 1958 J-200 with his name in the neck. I have a Grammer guitar he played on his television shows.”

What do you think it is about country music that still speaks to people today?

“Jimmie Rodgers laid it down: it’s about trains, gamblin’, ramblin’, cheatin’, hoboin’, sin, redemption, jail, mothers, home, dying, bills. Again, back to Woody Guthrie. It’s about the human condition. And everything that Jimmie Rodgers laid out, according to the headlines of your local newspaper today, all of those subjects are still relevant, wide open and on fire.”

Much of the country genre has become sugary. But do you think there are still flashes of greatness?

“Yeah. A good recent example is I saw Patty Loveless and Chris Stapleton sing You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive at the [2022] CMA Awards. It was like a moment of truth and a breath of fresh air in a stream of saccharine country music. And the place was silent, like it was church. All of those artists were standing there with their mouths wide open, looking at the truth.

“And that tells me that the truth still stands, and when people play with what’s authentically in their hearts – instead of chasing trends and charts and being a part of a parade that’s not going to be here in five years – country music reappears. The other stuff is good for disposable business. But the heart and soul of country is still very much alive and well. I think the reason it is still here is that it speaks the truth when it does its job. It sympathises with people. It says, ‘I understand. I’ve been there.’”

- Altitude is out now via Snakefarm.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.