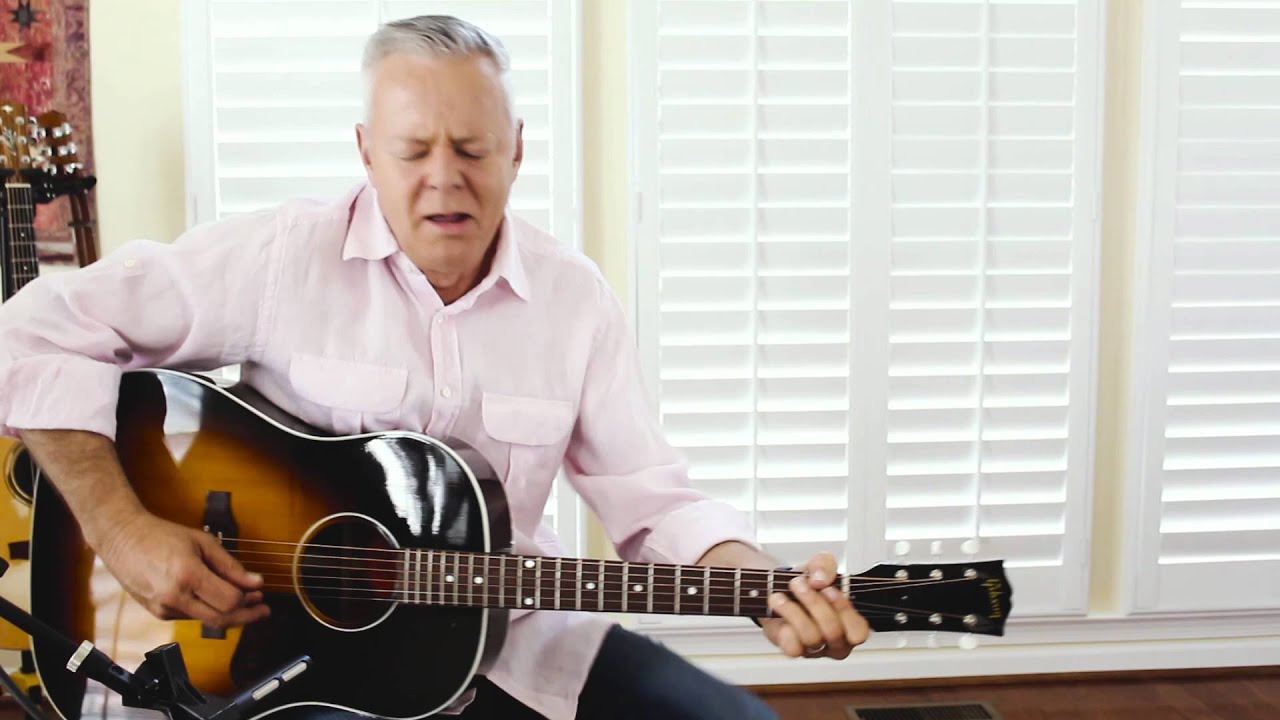

“I’m always true to the melody but I try to do something unique with it. That makes it sound like me, even if it’s a Paul McCartney or John Lennon song”: Tommy Emmanuel on the art of arrangement, performance and why there’s no shortcut to virtuosity

Tommy Emmanuel does things with the acoustic guitar that defy belief. He does things with pop-culture's canon that blow our mind. He walks us through his approach, sharing wisdom as he goes

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tommy Emmanuel is a master of acoustic guitar. And yet, at its core, his approach is simple. “I never think about technology,” he says. “All I’m looking for is good sound. Just give me one great sound, and I’m off. That’s all I’m looking for.”

Tommy has learned a thing or three after nearly 30 solo albums, tons of guest spots and more accolades than you can shake a stick at. He’s a virtuoso of the highest order, but the beautiful thing is that he’s never stopped learning. What’s more, he revels in teaching.

“If you’re just picking up the guitar,” he says, “you better learn some chords, song structure, and as many songs as possible. You’ve got to learn how songs are constructed, how to count the beat, and when to change. Learn how to get that all together.

“People approach me and say, ‘I want to play Lady Madonna like you. How?’ I say, ‘How long have you been playing?’ They say, ‘Two years.’ And I’ll say, ‘Forget it!’”

Tommy reiterates that if you want to be the best, first, you’ve got to get down to basics – and never forget them.

“It’s another world doing all the harder stuff,” he says. “So you’ve got to learn to do it all properly. Learn why the melody works against chords. Figure out how to make that feel like a singer. But all that comes with experience and time. I encourage young people to use tabs as a roadmap, but it all comes down to learning song structures, chords, and, most importantly, things you can work on with other people!”

So, what’s the first step to getting it right – specifically, your style of cascading harmonies?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“If you want to get it right, you’ve got to break everything down into its slowest and easiest way and then work it up. There’s a lot of variations of how to use harmonics in music, but I’d say the best songs to showcase my Chet Atkins style of cascading harmonics would be songs like Somewhere Over the Rainbow, Michelle, or Secret Love – songs that I’ve specifically arranged so they can be all around that technique.”

Break down that technique.

“I play the harmonic with my thumb, while my index finger is just barely touching the string up the octave. So I’m getting the harmonics up the octave and using my thumb to pluck the string. And then, if you look at my right hand, my middle finger is my balancing point. It’s like the central point of my hand, and I use that as my balance point.”

And then there’s the open notes you often have going on…

“Right. So then, with my third finger, I play the open notes. I make the harmonic and the open note kind of melt together. When you do it right, the ear can’t really tell which one is which until you hear the sound of the harmonic being picked. So I can get all kinds of sounds using that particular technique.

So that all comes from things you picked up from Chet Atkins and Lenny Breau and then made your own? That’s important, as a lot of people are nervous about copying their influences, but sometimes, it’s not copying but a starting point. But you use other types of harmonics, like juxtaposing chiming chords.

“It comes directly from Chet Atkins and Lenny Breau. And then, there’s other kinds of harmonics, where I might play a passage, or just hit a chord in the middle of a passage with the palm of my hand. I’ll barely touch the string with my palm and hold the chord so the chord chimes up the octave.”

It’s reminiscent of certain lap steel techniques.

“It actually comes from the Hawaiian technique of playing lap steel! When I was a kid, I learned all that because my mother played Hawaiian steel, and my sister played and she would play the melody. Then she would take a break, like the second time around, and quote the melody up the octave, using her palm to strike the harmonics.”

This is important for young players to know because it shows that there’s not just one way to approach harmonics.

“Exactly. So, that’s the couple of techniques that I use, and, of course, there are harmonics all over the guitar. Open harmonics, anyway. You’ve got to spend time looking for them and remembering exactly where they are so you can hit it dead in the middle of the passage.”

Another integral part of what you do is your use of alternating basslines. What’s your crash course as far as that goes?

“The best thing to get you going on that is finding the song that needs a moving bass part. I remember when I first heard Chet Atkins playing A Taste of Honey, which is a song that The Beatles recorded. You know what? I’m going to put you on speaker and play it for you. Are you ready?”

Oh, absolutely. Let’s hear it!

“Here’s how the song goes [Tommy picks up his acoustic guitar and demonstrates how to play it]. In order to make that melody and make the bass move, Chet created this thing, and it’s kind of what a bass player would play.”

So, how did you learn to make the moving bassline and that melody work together? It’s almost like two people are playing, but it’s just you.

“In order for me to work out how to play that moving bassline and have the melody, I had to learn everything at once. The best part about moving bass parts is they just keep the song moving along. So it’s not necessarily about the technique, but finding the right songs that really suit that and need it.”

This is a good example of how sometimes the best technique applied to guitar has nothing to do with technique but incredible love and desire for the instrument. With that in mind, what’s your best advice for those who are at the point of arranging songs?

“I’m a producer and arranger. I’ve always got those hats on. I’m not just a player, I’m everything, and I’m looking at it from every angle. Everything must satisfy me. When I find a song that needs the right kind of approach, I make sure that everything is covered and that the melody has a life of its own.”

Many people find it challenging to shift gears, step outside the music they’ve written, and look at it objectively. Do you find that to be the case?

“There’s a lot of things that a producer will do. He’ll take a song, listen to the song, and say, ‘Okay, instead of that chord, let’s make it more interesting. Let’s surprise the listener. When we hit that note, let’s make it an unresolved chord and resolve it in the next bar.’”

I’m always looking for the element of surprise and the chance to do something musically different and unexpected

So it’s about creating interest through the unexpected.

“Right, it’s unexpected. And then, there’s little things that I’ve learned along the way a long time ago. I’m always looking for the element of surprise and the chance to do something musically different and unexpected. There are enough people out there just playing overs, trying to play it exactly like the record. I tend to do the opposite.”

That’s another important point. Many players are fearful of altering something established or beloved. But sometimes, that’s necessary.

“I tend to take a song, even if it’s iconic, like a Beatles song, and I’m always true to the melody but I try to do something unique with it. That makes it sound like me, even if it’s a Paul McCartney or John Lennon song.

“I always have a deep respect for the song, but sometimes, like John Lennon’s Imagine, I try to interpret the song in the best way I can. But there are little musical bits along the way that are part of that arranger and producer’s skillset I have.”

Getting stuck is another big part of playing guitar that isn’t mentioned enough. No matter how long you play, it’s inevitable.

“Oh, I’m always stuck! Just this morning, I was playing my very latest composition, and part of me wants to change it already, and I only wrote it a couple days ago! So I started messing with it, but I’m always waiting for inspiration. I’m always waiting for something to happen that will cause me to compose and have great ideas that I’m excited about.”

Do you have any tried-and-true tricks for getting out of a rut when you do get stuck?

“You know, it’s not something you clock on and off. Sometimes I get the best ideas at the weirdest times, and I don’t always have a guitar close by. So it’s not something you can manufacture. I’m always looking for something to give me an idea. Just give me one idea – I’ll run with it, you know?”

And sometimes those ideas come from unexpected places.

“Sometimes I get them from watching a movie or meeting somebody. Or maybe I’ll get some idea one day, and it turns into a song, like a song of mine called Drivetime. I wrote that song a long time ago, and I had been seeing Stevie Wonder live, and when I got home, I got my guitar and started playing this little phrase.

“It’s C# minor, and I just walked around the house playing that for hours. I really, really loved it, and then, I thought, ‘Well, okay, that’s the foundation. Now, I’ve got to tell a story. Where am I gonna go?’”

That piggybacks onto what you were saying before about embracing the unexpected.

“Right. So, from that one idea, came this song, some of the first bridge, and then, the second goes around again, and when you least expect it, it goes into a second bridge, which is different. I put that all together from just one good idea. But then, my arranging and producing skills take over, making the whole thing interesting and going somewhere unpredictable.”

You mentioned earlier that you’ve got a new composition and are already tweaking it. For many guitarists, overthinking is a problem, but finding a balance between the blueprint and the unpredictable is significant.

“A good example of that is my song Angelina. The harmonic ending of that song – when I first wrote the song, that was the introduction. But when I got to the studio to record, it all my instincts told me, ‘Don’t give away the harmonic ending at the start’. So, I came up with the introduction that we know to Angelina right there on the spot.”

Should players learn to trust their instincts?

“I think so. In that instance, it seemed to work. I recorded it, and everybody loved it. I brought the harmonic ending in at the beginning instead of giving it away too early. If you’re an enthusiastic and excited composer, you’ll know when you’re onto something good. But eventually, when you record that’s when you have to say, ‘Okay, now we get serious about every little millisecond of this song.’”

As far as gear goes, there’s so much of it out there. It’s hard to know what’s worth one’s time. How do you navigate that?

“When I play a show, I have one pedal on stage. It’s a tuner. That’s it! I have no loopers, no chorus, no delays – all that is done for me by the sound person. The most important thing for me is good sound, and that’s it. But when I go into the studio, I’m in heaven, and I’ll tell you why – I wear headphones! I sit in front of microphones and play acoustically, and I can get the engineer to give me whatever I need into the headphones.”

So it’s less about new gear and tech and more about pure sound?

“Right. We’ll keep working on it until we get the mix and we monitor it. The sound in the headphones causes me to go deeper into my abilities and creative ideas. But when I’m on stage, it’s a completely different beast – I’m out there to totally knock people’s socks off.

“I’m there to give them the best time of their lives and to play the best I can. But when I’m in the studio, it’s about getting the feeling right, diving into the song, and capturing a performance. My best advice is that if you can’t get it in one or two takes, there’s something wrong.”

And in terms of live performance, what’s the best advice you can give?

“You have to have the right songs. It has to be something good. You want to play something with feeling that I can pour myself into, have fun with, and surprise an audience with. And you have to have a repertoire of different feelings, sounds and styles.

“You might come out guns blazing, and you’re taking the audience with you, and when you finish that, you might go into something more traditional. It’s about putting a smile on their faces and making them forget about everything. It’s all about the songs. If you have the songs, then your instrument can help you be the painter.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.