Interview: Joe Bonamassa Discusses Gear and His Return to Blues-Rock on 'Driving Towards the Daylight'

It’s Saturday night in Cleveland, April 14, and blues guitar legend Freddie King has just been posthumously inducted by ZZ Top into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s “Early Influences” category.

As the curtain behind the podium in Public Hall parts and the wailing starts, Joe Bonamassa is standing on the big stage shoulder to shoulder with Billy Gibbons and Derek Trucks to pay musical tribute to the style’s late prince of the feral six-string.

They tear out a jaunty version of King’s 1961 instrumental hit “Hide Away,” named after a Chicago blues dive, and then gear up for “Going Down,” a tune written by Memphis songwriter Don Nix that King made a staple of the modern blues-rock canon. Gibbons plays it cool and tone-y, sticking to the song’s bones but sucking on their marrow. Trucks goes for fiery understatement, emulating King’s switchblade finger picking with his slide.

But Bonamassa gets closest to the blood-gorged heart of King’s version, practically launching his cherry Gibson ES-355 into space as he hammers, bends and whinnies the performance to its apex. No other guitarist onstage that night will breathe similar fire until Slash and his Axl-less cohorts in Guns N’ Roses get their due.

That’s natural, because Bonamassa is the roots-based six-string’s new king of pyromania. His songs catch like sparks in the hearts of his large and growing legion of fans, slow burning their way into sonic and emotional statements typically punctuated by conflagrant solos full of elaborate bends, extended chords and sheer gut-level bursts of energy, all sculpted with a wide, graceful and heavy tone that recalls the classic British blues of the late Sixties and early Seventies — but with decidedly modernist twists in their lyrics, the judicious application of effects, and a fearless sense of fulfilling a destiny Bonamassa stepped into as a child prodigy in the late Eighties.

A lot has happened since then. Bonamassa’s gone from jamming with blues deacons like B.B. King to leading his own band across the globe and playing hot and heavy with Black Country Communion, a hand-picked assembly of world-class rockers that includes singer Glenn Hughes and drummer Jason Bonham. The handpicking was done by Kevin Shirley, who has been Bonamassa’s creative guru since 2005, producing his last six solo discs and both Black Country Communion albums.

Shirley’s gambit has been to push Bonamassa to new artistic heights, and that’s paid off in elevated commercial planes as well. Bonamassa has sold millions of albums and can today sell out U.S. theaters and European arenas. That’s a far cry from the barbecue-and-blues club circuit he was playing less than a decade ago.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

For Bonamassa’s latest album, Driving Towards the Daylight (Buy on iTunes), Shirley kicked his butt once again by putting him in Las Vegas’ Studio at the Palms with a heavyweight cast of all-star “sidemen.”

These include no less than Aerosmith’s Brad Whitford plus his son Harrison Whitford on guitars, former Bowie- and current Bonamassa-band bassist Carmine Rojas and the great session drummer and Letterman house band member Anton Fig. The result is an 11-track album of originals and reimagined blues classics, plus Tom Waits’ hopeful “New Coat of Paint.”

“I looked around the studio and saw all these great players,” Bonamassa says, recalling the first day of sessions. “I looked in the amp room and it was filled with ‘Plexi’ Super Basses and Super Leads, four Marshall Jubilees, two original Dumbles, a Trainwreck, a couple Tweed copies. I looked at my guitar rack with two Les Pauls from 1959 and one from 1960…and I thought, Dude, if you fuck this up, you can’t play and you’re an idiot.”

Rest assured that, at age 35 and at the top of his form, Bonamassa is no idiot. Just ask Billy Gibbons and Derek Trucks. And if Freddie King were still alive, he’d probably put a good word in for him, too. But we caught up to Bonamassa motoring along the California coast, and he spoke for himself.

GUITAR WORLD: Your solos have an arc that tells a story. What’s your secret to constructing an effective solo?

Solos are basically 16-to-24-bar marathons. If you run a marathon, you can’t start sprinting, but at the start people need a little fireworks to grab their attention. Then you have to back off and say something with a melody before you start barnstorming. And then there’s pacing. A lesson from the old blues guys is they were never in a hurry to get to anything musically. They were like, “It’ll happen when it happens.” I love that idea.

Your own playing balances old-school blues tradition with the British flag wavers of the Sixties. It’s like a balance of Howlin’ Wolf and Robert Johnson with Jimmy Page and Rory Gallagher.

Initially, I had no clue that the Lonnie Johnsons and even the Robert Johnsons of the blues world existed. I just wanted to play like [Free’s] Paul Kossoff, Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton when he was in Cream. As a 10-year-old, the subtleties of traditional blues are lost on you, especially after you hear Alvin Lee on “I’m Going Home” busting out the ES-335 with four double-stacked Marshalls. British blues was my favorite music, and it still is. It’s big and ballsy and dangerous, and that all appeals to me. The country blues came later.

After making more-wide-ranging solo discs and playing and touring with Black Country Communion, you’ve returned to blues-rock with Driving Towards the Daylight, but are you still consciously pushing your palette in a nastier direction?

When I joined Black Country Communion, it was my excuse to make records like I couldn’t make under my own name. I’m actually much more of a rock player than many people think. That aspect of my playing has been creeping in, and it feels more comfortable now that Black Country Communion have been accepted. If you listen to my records—and I just had to go back through them to pick songs for a live acoustic DVD we’re recording in Vienna in June—it’s pretty clear that if you call them “blues,” you’re using the term liberally.

Kevin Shirley and I started working together in 2005. We set out to do something different and original with the blues as the basis. If we were interested in playing it safe, I’d still be playing to 300 people a night — on a good night.

You began your career as a youthful prodigy, opening for B.B. King at age 12. Did that set up certain expectations that you had to overcome?

I think the number of laps I’ve made around the sun has helped. The initial reaction I got was, “Okay, this kid thinks he can play.” But I didn’t think anything. I just liked to play and have fun. It was an excuse to get out of class early.

Now, 13 albums, three live DVDs and many, many world tours later, people seem to be just realizing I have gray hair. Some people still look at me as “the kid,” but it’s great to meet people who have followed my journey from when I was going to gigs with a Twin-Reverb and a Tele in my parents’ Lincoln Continental.

How would you describe the arc of your development as a player? I’m especially curious to know when you felt you’d turned a corner and stepped into your own musical identity.

I still feel I’m struggling to step into my own shoes as a musician. Every day I work on refining my phrasing. Whenever I hear my playing, I can’t detach from my influences: there’s my Jeff Beck, there’s the Clapton bit, the Eric Johnson bit, the Birelli Lagrene bit, the Billy Gibbons.

What do you focus on when you work on technique at home?

It’s all about the internal bends. A guitar is so tactile, and when you’re playing bends—and bending notes is a big part of my style—there are so many notes within the note you’re bending from and the note you’re bending up to. For me it’s about filtering out the bad notes and finding these little quartertones, as you drop down the bends, to make a very crisp statement that people can feel.

I’m still a teenager in that I’m eager to learn, even moreso than I was in my twenties. At that point I thought, Well, I can play pretty fast and I can hold my own with some of these cats. But I’ve learned that there’s never a limit to what you can learn on the guitar, or in life.

You often bring an armada of guitars onstage, including your signature Les Paul Studio goldtops. What are your favorite stage and studio instruments?

Besides the goldtops, Gibson also did some in sunburst for me, and they painted one black, so I’ve been playing those a lot. I also have three real ’59 Les Paul Standards, and I’ve been playing two of them onstage. I like my show to be a spectacle for gear heads.

I play in front of three double-stacked heads on three custom-made Marshall cabinets. Over the course of a concert, you’ll see a ’61 dot neck ES-335, a ’53 Tele, a Firebird I and two ’59 Les Pauls come out. I know if I were in the audience it would be fun for me, because I’m a gear head like everybody else. I try to keep the guitars I play with Black Country Communion separate from the guitars I play with the solo band.

I’ve never been like a Stevie Ray Vaughan or a Rory Gallagher or Derek Trucks—the cat who has found a guitar so perfect for him that he and the guitar are practically synonymous. Part of it is that my attention and tastes wander.

I’ve always had a lot of guitars, even when I was dirt poor and living in New York on peanut butter and Ramen noodles. I would scrape together just enough money to pay the rent, and if I had an extra $500 in my pocket I’d get another guitar. Or I’d trade. I’m the son of a guitar dealer, so I learned how to horse trade.

Do you have a single favorite instrument?

I have a 1959 Les Paul Standard sunburst, serial number 90829. It’s the first ’59 that I bought, and I never thought I would pay that much for anything other than a house. That guitar is perfect for me. The neck shape, the way it plays and responds—no matter how good you are, that guitar doubles back and says, “Is that all you’ve got for me today?” I was just gone for six weeks to Europe. I opened up the case to that guitar when I got home, and I got the same thrill I had when I opened that case for the very first time.

You’ve made seven albums, including the Black Country Communion discs, with Kevin Shirley. What’s special about working with him?

Kevin is always the best musician in the room, and he knows exactly what to do to up the ante. He also has the ability to envision how a finished album is going to sound before you enter the studio. With this new record, Kevin got me out of my comfort zone in a good way, by bringing in heavy cats who I don’t normally play with, like Brad Whitford and Anton Fig, so I had to react to the band differently. You have to be challenged; it’s good to be the weak link. That forces you to elevate your game.

Kevin has taken me from making just average blues records to making more widely accepted music. Before I started working with Kevin, I’d be playing to 300 sweaty dudes every night who’d throw me devil horns when I’d quote “Heart of the Sunrise” during my encore. Now I play for thousands of people at a time—from families with little kids dressed in suits and sunglasses like me to, well, girls! When’s the last time you saw girls at a blues concert?

It’s as rare as seeing the northern lights in the daytime. Kevin has made me make records that challenge me and challenge listeners. If you pick up a Joe Bonamassa record you’d don’t know if you’re going to get a bouzouki or a Hammond organ or a bunch of traditional Irish players on the tracks. There are no rules with Kevin.

When I first talked to Kevin about producing me, he came to a gig in a little town in Illinois at a small blues club, and we played too loud for the waitresses to take the orders. It was one of those of gigs. And he came on the tour bus — I thought I was hot shit because I had a tour bus—and he said, “I thought you played really good, but the band’s not right. Your image has to change. You dress like a slob. And we need to get you good songs. If you want to keep making ‘okay’ blues records, I’m not the guy. But if you can trust me 100 percent, I can help you get to another level.” And he did.

The new album’s title track has a cool arrangement, blending electric and acoustic guitars, dynamic textures and ripping leads. And that blueprint gets used a number of times. How did that approach develop?

Most of the album was done on the fly, and there were some hairy moments, like the arrangement of [Robert Johnson’s] “Stones in My Passway.” I could not feel it on the two and four to save my life. Everybody else was feeling it. After the 15th take I had screwed up, they were all going, “Dude, it’s right here!” I felt like the ultimate awkward teenager playing basketball in front of the hot chick during gym glass.

Blues might seem simple, but when you get deep and stretch it, it’s a real challenge. Howlin’ Wolf’s “Who’s Been Talkin’ ” is one chord. But when you’re holding the one over where the four chord would normally be, that can trip you up.

You’re using a double-neck Gibson EDS-275—the “Stairway to Heaven” guitar—on “Stones in My Passway.” That’s an unusual choice.

It’s a 1966 I borrowed from a friend. It’s the nicest double-neck I’ve ever played. I tried playing the song on a six-string but decided I need to do something else with it. The guitar is tuned in open E capoed to A. Kevin was adamant about copping the Robert Johnson licks correctly. The arrangement is based on Robert’s playing, but I decided to play it on electric to take it to another zone.

“A Place in My Heart” is an epic ballad, with a sweet, overdriven tone that reminds me of the late Gary Moore. How did you get that tone?

Whenever I record, I have two rigs. I always bring my live rig. I figure if everything goes tits up, my Marshall Jubilees and the Van Weelden Twinkleland will always sort me out right. And that’s what that was—my live rig. Kevin said, “We need to get that big solo happening, à la Gary Moore.” So I think I goosed up the gain a little, and I used a ’59 Les Paul. It’s a Bernie Marsden [of Whitesnake] song that he wrote for Gary, who never got to it.

“Lonely Town, Lonely Street” has a swirling Hendrix-style guitar and organ climax. Was that planned?

Well, we had a rough map, but like Lewis and Clark’s map, it was kinda vague—like, “We think the ocean’s over that way.” I plugged in a Way Huge Ring Worm ring modulator for one of those really crazy bits where you step on it and it slaps your rig around.

That ending happened in the studio when Arlan Schiefbaum, the keyboard player, and I started passing fours back and forth. We cut that song the same day as “Too Much Ain’t Enough Love” and a version of “Lazy” for an Australian Deep Purple tribute album, so we were already in keyboard-and-guitar mode.

How did you develop the core riff for “Dislocated Boy”? That repeated lick takes it into the same hypnotic space as Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks.”

That whole song took me 20 minutes to write. I just played the riff one night and sang whatever I was inspired to sing over the top of it while recording with GarageBand. That was a case of how a good instrument can inspire you. I bought a Thirties Martin 0017 through my guitar repair guy in Los Angeles.

Somebody had dropped it off and left it there for four years, because they didn’t want to pay for the repair. Within about seven minutes of playing that trance-like figure that became “Dislocated Boy,” I knew I had something special, like I did with [2009’s] “The Ballad of John Henry.” When we cut it, it got heavy fast, with us just jamming on the one. I make no apologies for being a fan of the sludge. I gravitate toward those midtempo, swampy, one-chord blues with an English twist.

What advice would you give blues and roots guitarists who are interested in pushing beyond the traditional boundaries of the styles?

It’s good to listen to all kinds of music to bring it into your core. If you’re a blues player, listen to jazz, heavy metal and experimental stuff. You’ll always find little gems that feed your true passion.

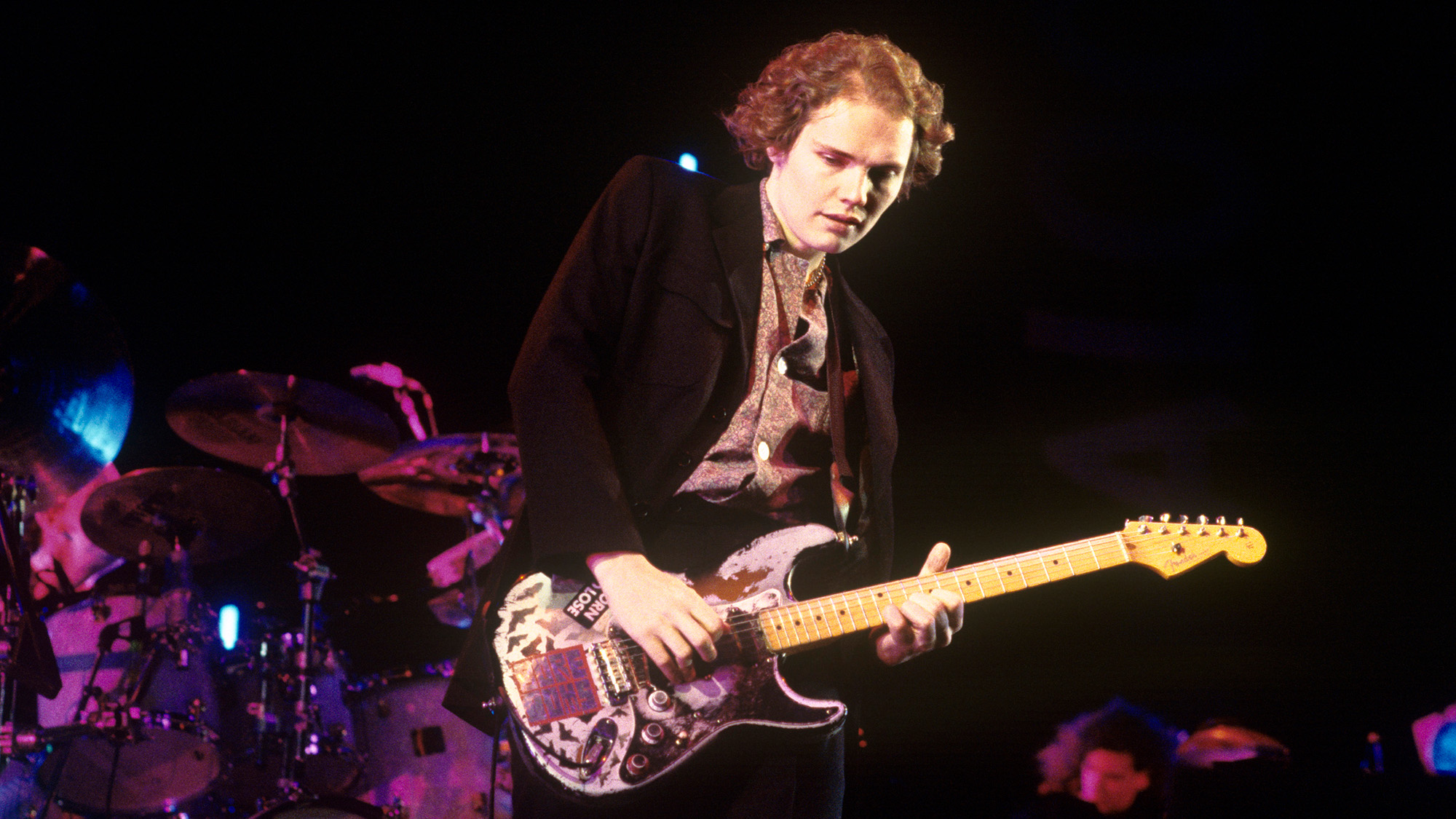

Photo: Jeremy Danger

In our How to Play Blues & Blues Rock and Blues Rock Master Class DVD Combo, Guitar World's own associate editor Andy Aledort teaches you beginning, intermediate and advanced levels of blues rock guitar. It's available now at the Guitar World Online Store.