Five Classic Blues Turnarounds: Bars 11 and 12, Delta Blues Style

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A blues turnaround occupies the final two measures—11 and 12—of the 12-bar form.

Bar 11 typically contains some sort of lick or phrase over the I chord harmony, and bar 12 shifts to the V chord, resulting in tension that sets up resolution to the I chord at the top of the form.

Often, however, early acoustic Delta bluesmen would just sit on the I chord in bar 12.

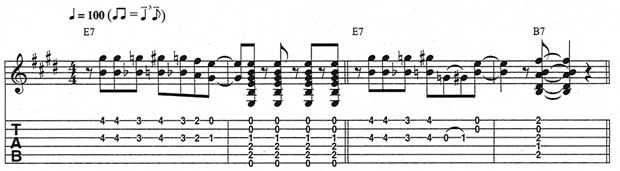

For example, in Charlie Patton’s “Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues,” the turnaround that's similar to the one shown in FIGURE 1, begins on the b7th (D) and descends down the Mixolydian mode to the major 3rd (G#), skipping the 4th (A) along the way. Notice that measure 2 sticks with the I chord (E).

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2A features a 6ths-based turnaround lick similar to the one Patton used in his signature tune, “Pony Blues,” while FIGURE 2B varies things by inserting the V chord in bar 12.

FIGURES 2A-B

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Likewise, Baptist preacher-turned-bluesman Son House would occasionally focus his turnaround entirely on the I chord. In “Downhearted Blues,” House made use of descending and ascending 7th chords to turn the tune around, as in FIGURE 3.

FIGURE 3

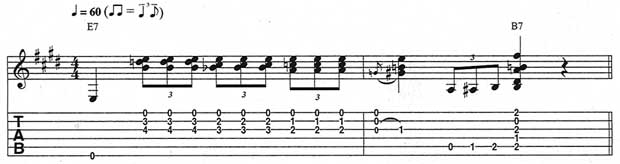

Robert Johnson wasn’t called the King of the Delta Blues for nothing. By the time of his death in 1938, he had solidified many of the stylistic elements that have come to define modern-day blues. One such element was the descending turnaround pattern seen in FIGURE 4.

FIGURE 4

- The distinguishing characteristic of this turnaround—featured in such tracks as “Kind Hearted Woman Blues” and “Milk Cow Blues”—is the top-string note, which acts as a pedal tone against the descending chromatic line from the b7th to the 5th.

For easiest execution, anchor your 4th finger on the 1st string’s 5th fret, then begin string 4’s descending pattern with your 3rd stinger at the 5th fret. FIGURE 5, meanwhile, is a variation on a turnaround that Johnson played in the intro of “Me and the Devil Blues.”

FIGURE 5

Since 1980, Guitar World has been the ultimate resource for guitarists. Whether you want to learn the techniques employed by your guitar heroes, read about their latest projects or simply need to know which guitar is the right one to buy, Guitar World is the place to look.