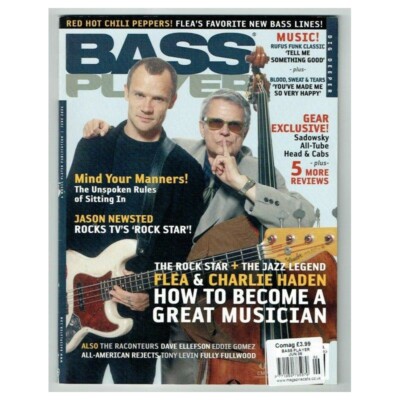

“All I wanted was to be a punk rocker and play the bass guitar. I went completely in the other direction from jazz, and now I'm trying to catch up”: When Flea met Charlie Haden – and had much more in common than you might think

From the Bass Player Archive: An interview with a bona-fide rock star and a veteran jazz legend

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was an early evening in June 2006, at the Hollywood studio of music photographer Neil Zlozower. Decades of rock photos covered the walls of a dark alcove that opened into a large, well-lit room, where a busy assistant on a ladder adjusted a huge backdrop.

“Is Charlie here yet?” The impending arrival of the veteran jazz bassist was clearly causing anxious excitement despite the bona-fide rock star already present. Flea responded by strapping on his '61 Fender Jazz Bass and stabbing energetically at its flatwound strings, escaping into his own musical world.

When Charlie Haden finally stepped from his hired limo, the whole place seemed to relax. The two bassists had never met before, and the reason for their meeting was an advertising photo session for Gallien Krueger, whose bass amps both players endorsed.

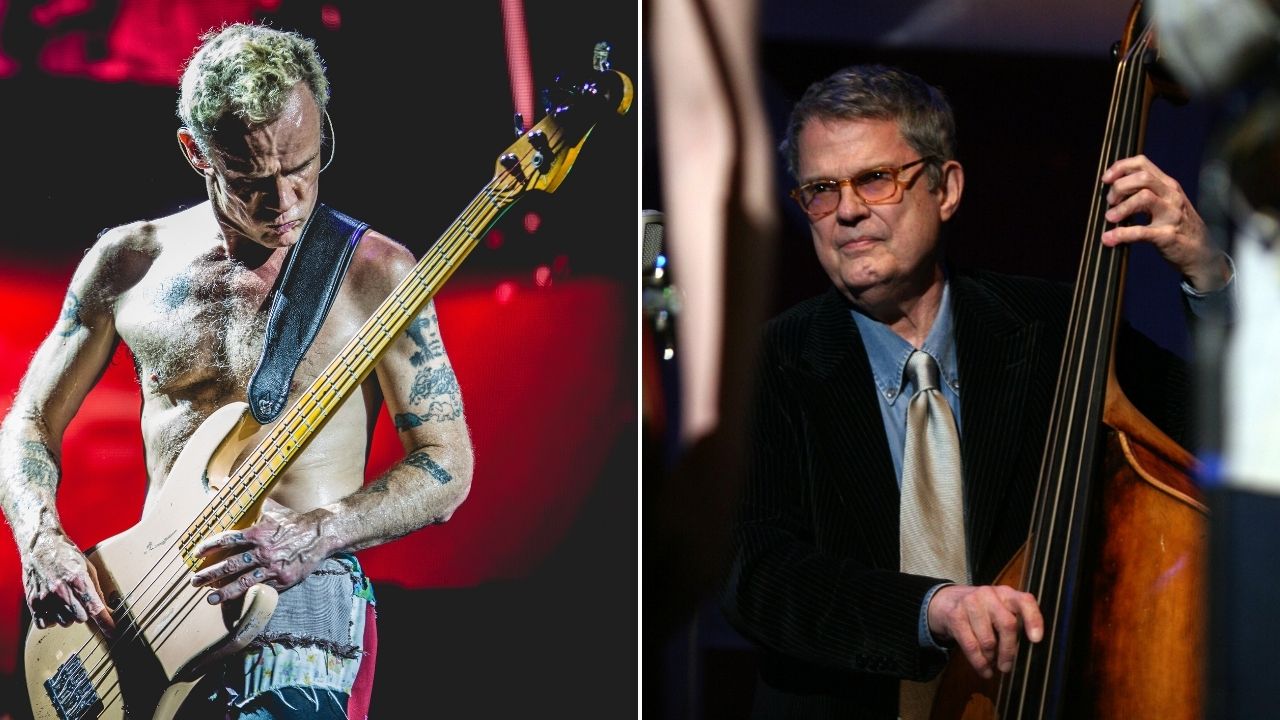

Flea's band is the Red Hot Chili Peppers, one of the most creative and successful in rock, and Flea himself is one of the genre’s most revered bassists.

He found his playing voice melding funk techniques with the intensity of punk, but his initial musical fascination was with jazz, a passion that has stayed with him decades after commending himself to a life in rock & roll.

Haden, whose lengthy resumé includes legends like Ornette Coleman, Keith Jarrett, and Pat Metheny, as well his own Liberation Music Orchestra and Quartet West, began singing on his family's country radio show.

Following his older brother, he took up bass, then got hooked on jazz after hearing pioneering saxophonist Charlie Parker. Haden joined Ornette Coleman's revolutionary group when he was still a teenager.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Flea: “You were singing country music as a kid. And all of a sudden you're playing with Ornette Coleman! What happened there? You were pretty young.”

Charlie Haden: “I was 19.”

Flea: “From singing country music at 15 to inventing free jazz with Ornette at 19 – that's a big switch. Four years isn't that long!”

Charlie Haden: “Before that, in the late '40s, there was no TV and I listened to classical and jazz radio constantly.”

Flea: “Did you study jazz?”

Charlie Haden: “I’m self-taught. One of my brothers played bass on the radio show, and he had some jazz records, but you're talking about Missouri. It was hard to find records, and nobody played jazz.

“I went to a concert in Omaha, Nebraska – Jazz at the Philharmonic with Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Billie Holiday, and Oscar Peterson – and when I heard Charlie Parker play, that was it. It was unbelievable. He had beautiful harmonies and beautiful melodies. You hear the gamut of beauty in his playing.”

Flea: “It's hard for me to fathom: not only that level of musical sophistication, but the depth of feeling. And to step so far beyond what had ever been done before on an instrument.

“When I was a kid, I had such an opportunity to get that education through my step-dad, who was a jazz bassist. I was 12 when my parents divorced, and all of a sudden I was living with a jazz musician who was having jam sessions at the house all the time. It changed my life.

“My goal was to become a jazz trumpet player, but then I got into my early teens and I had to rebel against my parents. All I wanted to do was be a punk rocker and play the bass guitar. I went completely in the other direction from jazz, and now I'm trying to catch up. I'm studying theory and trying to play along over bebop changes with the Jamey Aebersold books and everything.”

Charlie Haden: “On trumpet and bass?”

Flea: “Mostly on trumpet, but on bass, too. I regret not learning that stuff when I was young, but my path is my path and it's been really good for me.”

Charlie Haden: “Well, you still have that learning opportunity. I never discouraged my kids from what they were excited about, and they grew up hearing all kinds of music. They went in the direction they went in on their own; I just encouraged them.

“Josh used to say, ‘Dad, you have to listen to this.’ it would be the Meat Puppets and Black Flag and all kinds of punk rock. And I'd say, with a forced smile, ‘Oh, my goodness! That's great, Josh. It's beautiful!’

“Did you ever hear Jimmy Blanton play the bass?”

Flea: “On records, yes.”

Charlie Haden: “He was amazing. Duke Ellington's band came through St. Louis and played a dance – back then it was dances and not concerts. Afterward Duke went back to the hotel to sleep, and all the musicians went to an after-hours session.

“This young bass player was playing, and these guys flipped out. They went back and woke up Duke Ellington, and brought him to the session. Duke hired Jimmy on the spot, and the band left St. Louis with two bass players. Jimmy Blanton made all those records in 1940 and 1941, and then he got what they called ‘consumption’ back then, tuberculosis.”

“He got very sick in L.A. and they had to leave him in a sanitarium. Milt Hinton told me he went there every day to see him. Milt was playing in Cab Calloway's band at that time, and every night they'd dedicate a song to him. Milt said he was there when Jimmy took his last breath. He was 23 years old. But if you've ever heard him play ... man!”

Flea: “It's unbelievable how many guys die so young. Booker Little is a big one for me. He has one of my favorite trumpet sounds ever.”

Charlie Haden: “I played with him. He used to come into the Five Spot when I was there with Ornette and Don Cherry.”

Flea: “Did you ever play with Eric Dolphy?”

Charlie Haden: “I recorded with Dolphy on this album called Free Jazz with Ornette and Don Cherry, Freddy Hubbard, Billy Higgins, Ed Blackwell, and my closest friend in life, Scott LaFaro, who used to share an apartment with me in L.A. before I moved to New York.”

“Scott was killed in a car accident when he was 25. He played on a very famous album by the Bill Evans Trio called A Sunday at the Village Vanguard. That was one of the last records he made.

“He was a tenor sax player with his dad's dance band when he was in high school, and one night the bass player didn't show up, so his dad made him play. He started playing the bass and he loved it, but he had the concept of the horn in his head. You can hear it when you hear him play.”

Both of you started your musical lives with something besides bass. Has that affected the way you think about or approach bass?

Flea: “Since I played trumpet first, when I picture notes in my head, I make a valve pattern with my hand and finger it on the trumpet. I never think about the bass like that, and I'm sure that has a big effect on my approach to playing bass. I never think of notes as fret patterns. I always think about it on trumpet.”

Charlie Haden: “So you think of yourself as a trumpet player first?”

Flea: “I don't know!"

Charlie Haden: “The real answer is that the instrument really doesn't matter. It's the music. I tell my students that, especially the bass players. They have to take themselves away from the concept of the bass. It's really important to discover your own music, and you're not going to discover your music if you're trying to play like some other bass player.”

Flea: “I always say the same thing. Any instrument is just a vehicle to express who you are and your relationship to the world. No matter what level you're doing it on, playing music is an opportunity to give something to the world.”

Charlie Haden: “When I was a kid and my older brother played the bass on our radio show, I noticed that when he didn't play, the fullness of the music stopped, and I was really attracted to that sound. He wouldn't allow me to touch the bass, but the minute he left the house, I'd pick it up, put on a record, and play along.”

What's important to you in terms of your sound?

Flea: “As time goes by, I realize more and more how important it is to have a good sound. Recently, I've only been playing all-wood vintage basses, whereas before I didn't really think it mattered what bass you played. I was so into being raw about it and trying to get across what was in my heart.

“I always heard guys talking about using this or that amp, this or that setting, and certain strings, and I thought it was all bullshit. I thought what mattered was how you hit them and your emotional intent, and I still think that's the bottom line. I mean, Charlie Parker could have played some old piece-of-shit sax and it would have sounded like Charlie Parker.

“But now I treasure the instruments that I play more and more. So now I play a 1961 Fender bass, and I love the old wood sound. It sounds really nice; I think it's further away from being a tree and is more used to being a bass now.”

Charlie Haden: “I always look at the sound of the bass as being like a rainforest: I try to get a deep wood sound. There are so many jazz bass players who spend thousands of dollars for these old instruments, like the classical guys do, and then they proceed to put a horrible pickup on it, plug into a horrible amplifier, turn up the treble or reverb or whatever, and it sounds like an electric bass. So they could have saved all that money and got an electric bass to begin with.

“I want to get the sound of the wood, so I use an amplifier that's made specially for the acoustic bass, and I also use gut strings on the G and D, which bring the wood sound out of the instrument. For the A and E, the lower-vibration strings, I use Thomastik SpiroCore because gut strings would be too loose.”

Flea: “The most incredible thing about the upright bass – the few times I've played one – is the way you can feel the whole thing vibrate when you have it up against your body. It's like your body is resonating with the instrument. It's a very fulfilling feeling.”

Charlie Haden: “That's why I stand so close to the bass when I play. One night in 1959 I was playing at the Five Spot with Ornette, Don Cherry, and Billy Higgins, and I always play with my eyes closed – but I opened my eyes, and there was some guy onstage with his ear next to my f-hole. And I was like, ‘Who is this guy?’ And Ornette was like, ‘That's Leonard Bernstein!’”

Flea: “I grew up listening to anything I could get my hands on. The Beatles were first, but jazz was the real discovery. When I was 12 and wanted to be a trumpet player, it was all Kenny Dorham, Dizzy Gillespie, Freddie Hubbard, and Miles.”

Charlie Haden: “Did you ever hear Fats Navarro?”

Flea: “Oh, yeah. And Lee Morgan is really my guy, too. The fact that those guys could play like that still boggles my mind. Outside of musicians or real jazz aficionados, people don't even understand. They think jazz is wild and crazy, but they don't realize the discipline, work ethic, and academics that are required.”

“What it really boils down to is this: To be great, you have to be able to love and care way more than your physical body is capable of.”

How do you tap into that when you’re onstage or in the studio?

Flea: “I just try to be who I am and do the best I can. I love music, and I love connecting as a human being.”

Charlie Haden: “I always tell my students, if you want to become a great jazz musician, first you have to strive to become a great human being, with qualities of humility, and appreciativeness. Do that, and you might have a shot at becoming a great jazz musician.

“There is no yesterday, there is no tomorrow, there is only right now. And in that moment, everything changes because you see a different perspective of life. You see your complete insignificance in the world. Only then are you able to see your true importance to the universe. And that's what real humility is.”

Flea: “I remember being on tour and being miserable. I had broken up with my long-time girlfriend, I was unhealthy, I was stressed out, and I couldn't sleep. I was falling apart. I didn't want to do it anymore. I know I shouldn't be whining, being a big rock star and all that, but at the time I was very unhappy.

“Then one day I woke up and thought to myself, 'So what if I'm miserable? It's not about me, it's about going out and playing for people.' So I tried to forget about all my problems and concentrate on what I could give.

“We all have our burden – you can try to fill it up with drugs or some other kind of addiction, but the bottom line is that the only thing you can do is give.”

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.