“I hope people hear these albums and go, ‘Oh, this is where that legendary American rock guitar archetype is from’”: This unsung guitar hero's band was called the American Led Zeppelin, and his virtuosic playing paved the way for Van Halen and Satriani

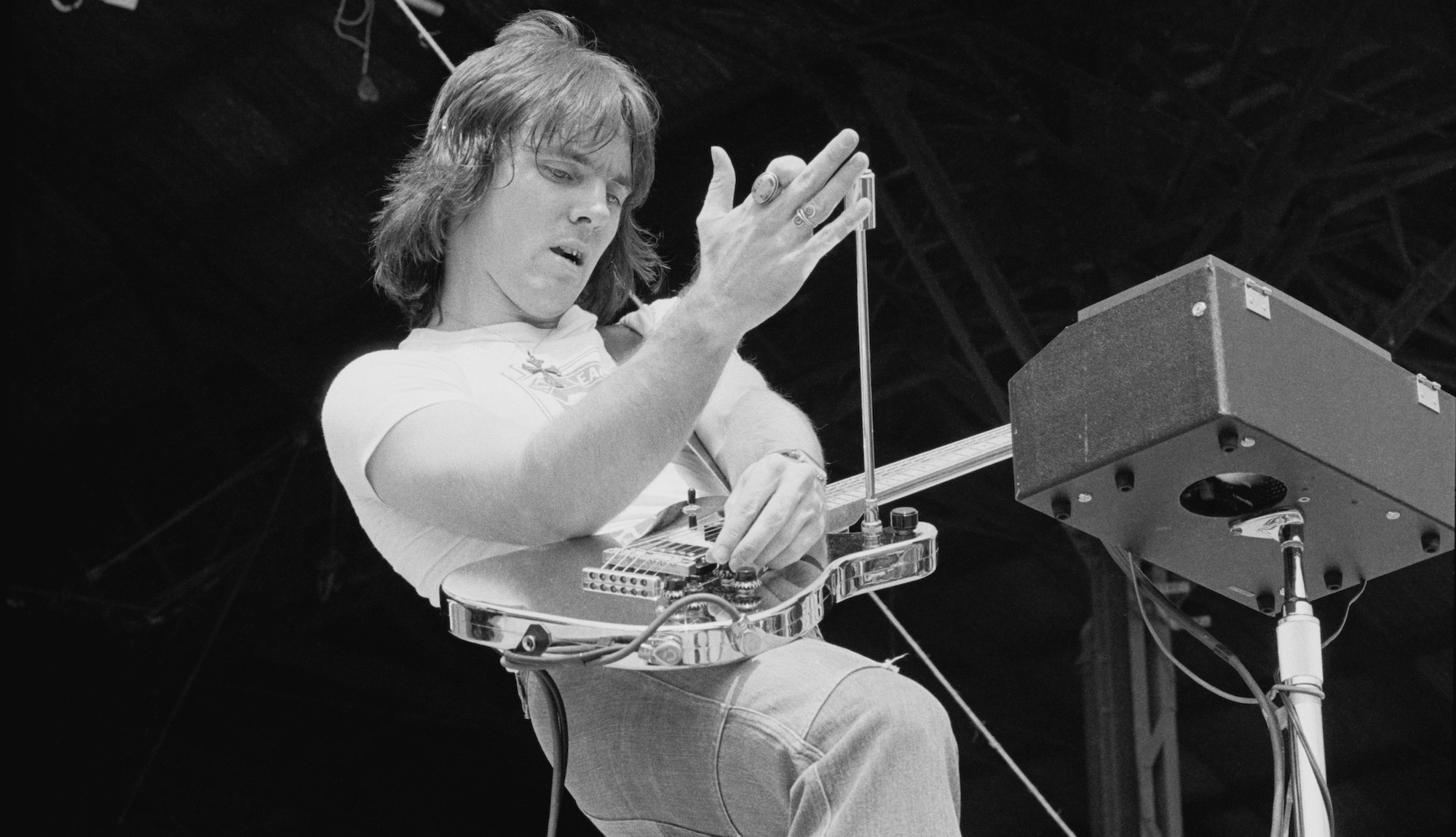

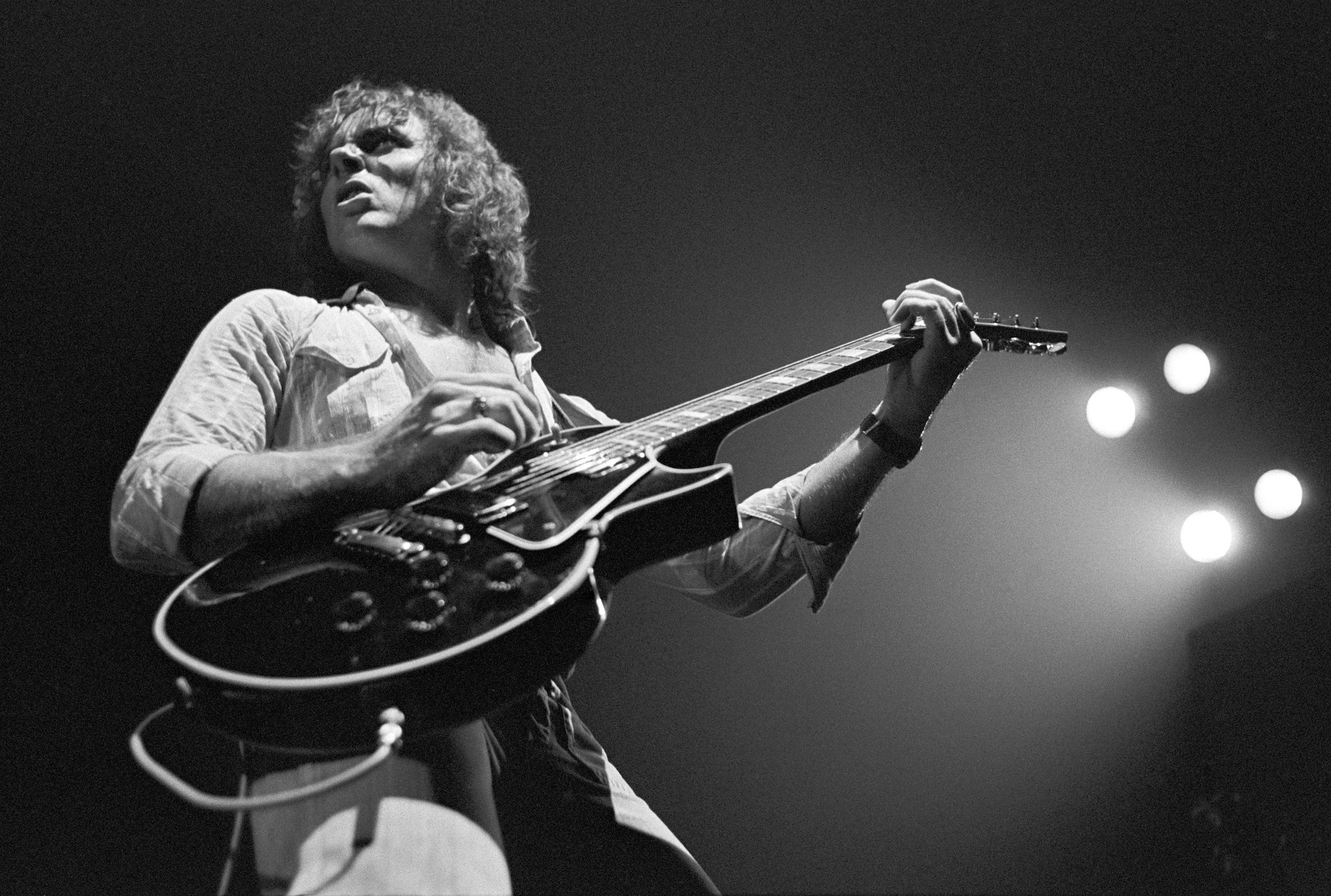

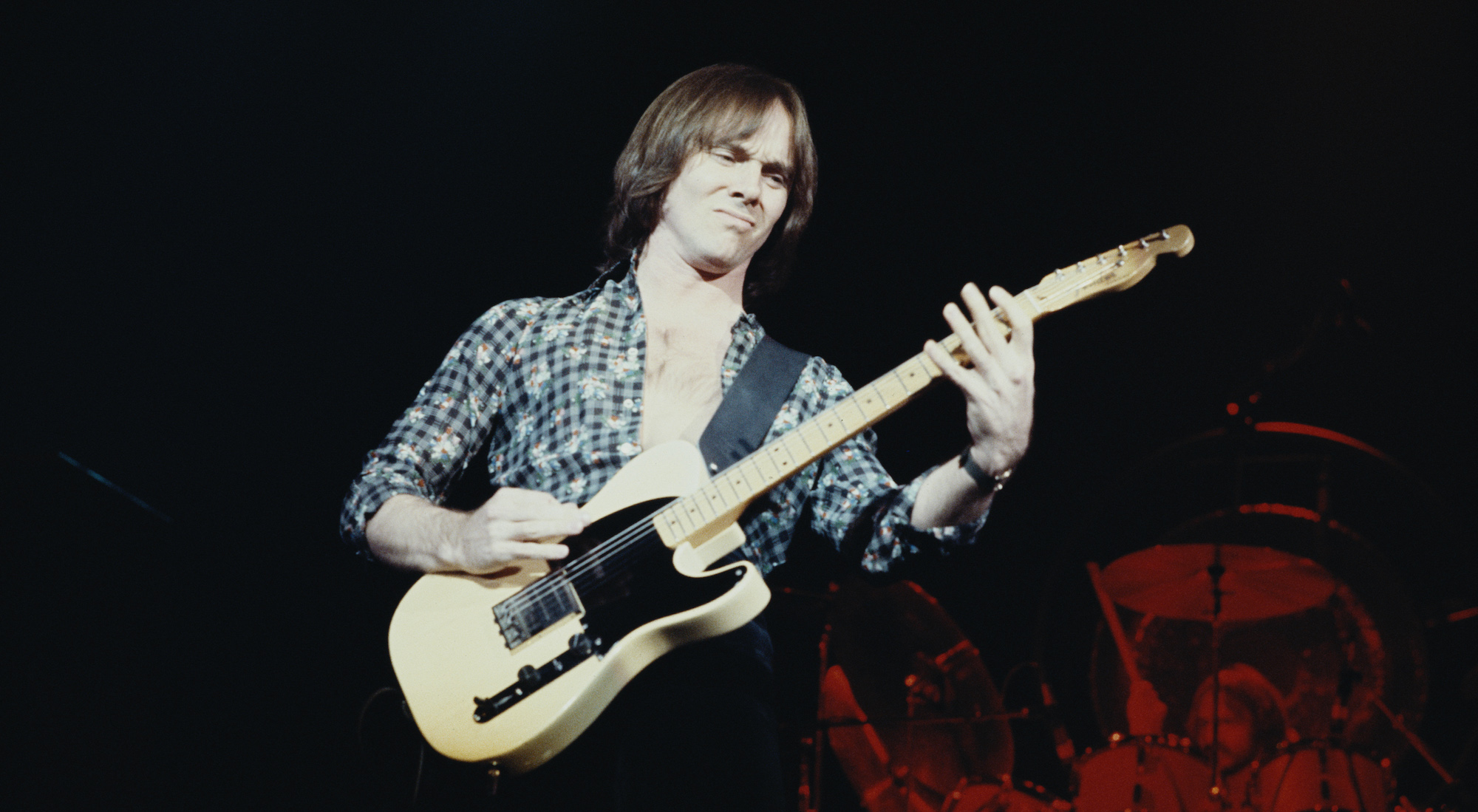

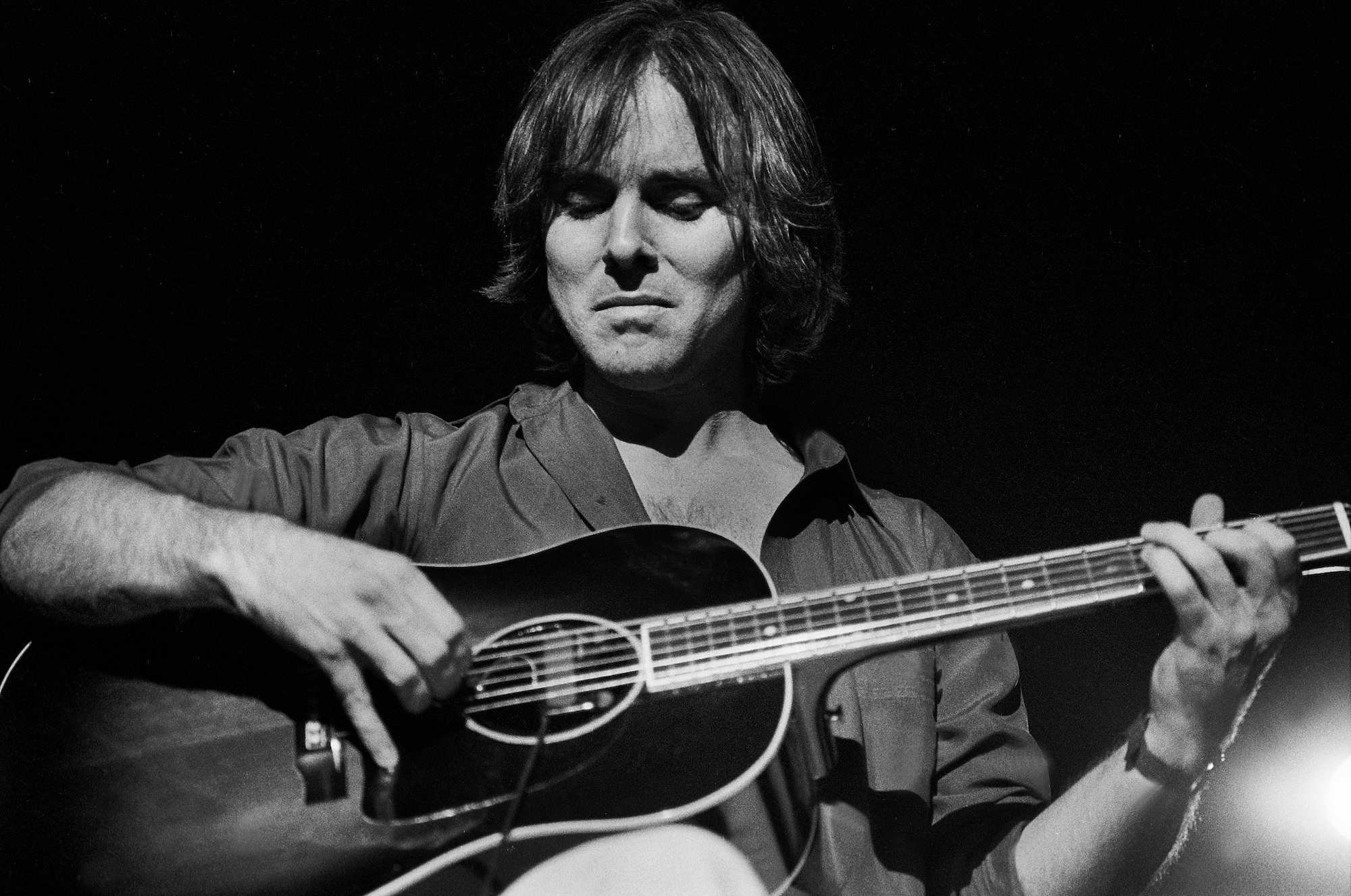

Often left out of discussions of the great rock guitarists of the '70s, Ronnie Montrose had little interest in chasing hits or following a consistent artistic path. Nonetheless, he left the guitarists who heard him spellbound

“RONNNNIIIIEEEE!”

With that epic battle cry, Mr. Big vocalist Eric Martin opens the floodgates on Heavy Traffic, the lead track on 10x10, the recently released final album from the late Bay Area–bred guitar giant Ronnie Montrose. It’s a fitting call to arms that immediately leads into a patented chunky power riff to signal that, yes, Montrose is in the house, he’s kicking major fretboard ass, and he’s taking names.

The hard-charging and hellbent bed track of Heavy Traffic lays down the gauntlet for a labor of love Ronnie initially set in motion with his early 2000s power trio tourmates, bassist Ricky Phillips (Styx, the Babys, Bad English) and drummer Eric Singer (Kiss, Alice Cooper), almost a decade before he passed away in early 2012.

With the full blessing of Ronnie’s widow, Leighsa Montrose, Phillips took over the reins as executive producer and spent another five years bringing 10x10 to the finish line by enlisting 10 different soloists, including Rick Derringer (Love Is an Art), Brad Whitford (One Good Reason), and Joe Bonamassa (The Kingdom’s Come Undone), as well as 10 different vocalists, such as Sammy Hagar (Color Blind), Gamma’s Davey Pattison (Head on Straight), Tommy Shaw (Strong Enough), and Glenn Hughes (Still Singin’ with the Band).

It’s a level of egoless teamwork that enabled Ronnie’s razor-focused vision to finally achieve fulfillment.

“I had to make some hard decisions to get the album completed, but I always followed the mantra of, ‘What would Ronnie do?’ He was right there with me, on my shoulder and in my ear, as my spiritual guide,” Phillips says.

10x10 is awash in the seductive blend of harmony, tone, and groove that fueled the internationally influential 1973 debut album from the singularly named Montrose.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When Ronnie joined forces with then-unknown vocalist Sammy Hagar, bassist Bill Church, and powerhouse drummer Denny Carmassi, the Montrose blueprint had already been stamped during his stints with Van Morrison (that’s Ronnie driving the melody on 1971’s Wild Night) and the Edgar Winter Group (the chilling runs on 1972’s chart-topping instrumental Frankenstein and its galloping hit partner track, Free Ride, are pure Ronnie to the core).

Indeed, all throughout the self-titled Montrose and its 1974 follow-up, Paper Money – both concurrently reissued by Warner Bros./Rhino, each packed with a treasure trove of bonus tracks, live cuts, and demos to boot – Ronnie forged an electrifying groove stencil that polarized guitar players on both sides of the Atlantic.

Songs dripping with endless hooks like Rock Candy, Rock the Nation, Space Station #5, and I Got the Fire were all seen as the sonic booms spearheading America’s mid-Seventies response to the British Invasion.

Many players and listeners alike felt Montrose was the missing red, white, and blue-blooded answer to Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, and Black Sabbath all rolled into one, not to mention being the precursor to the ensuing virtuosic likes of Eddie Van Halen and Joe Satriani.

“I do remember people saying Montrose was our answer to Led Zeppelin, which is a bold statement,” observes Phillips, who spent many of his formative years gigging in the Bay Area.

“I think we were all influenced by what was going on in England, and there were very few American bands firing back. But Ronnie, Sammy, Denny, and Bill – they were certainly firing back.”

My wish would be for people to hear 10x10 and the two Montrose reissues and then go, ‘Ohh, this is where that legendary American rock guitar archetype comes from!’

Phil Collen

Adds Marc Bonilla, the Bay Area guitar wizard who deployed Ronnie on a pair of his own early-Nineties solo albums and later filled Ronnie’s slot in a reformed Gamma, “The thing that was most impressive with Ronnie is what I call the deliberacy of his guitar playing. He was a carpenter, so he knew how to build things, which is what he did with his solos. He would start with a foundation down low on his Les Paul, and then he’d build his way up into a climactic event.”

British players also recognized Montrose’s singularity.

“I was a huge, huge fan,” admits Def Leppard’s Phil Collen. “My cousin got me into Montrose when the first album came out in England. I thought we were the only people who had it. Years later, when I met [Def Leppard lead singer] Joe Elliott, he said, ‘I thought I was the only person who had that record!’

“My wish would be for people to hear 10x10 and the two Montrose reissues and then go, ‘Ohh, this is where that legendary American rock guitar archetype comes from!’ That’s my hope, anyway.”

Ronnie was the kind of artist who followed his own muse, commerciality and lofty sales be damned. He was always on the hunt for the next challenge, rather than looking back on his past triumphs.

Notes Phillips, “People who truly want to break ground and not repeat themselves leave themselves open to not reaping the obvious successes of a repetitive performance. In many ways, Ronnie reminds me of Jeff Beck.”

Concurs Steve Lukather, “Artists like Ronnie never stop wanting to push themselves to learn other stuff that inspires new ideas and new music. That’s how Ronnie approached it.”

In his later years, Ronnie continued to veer between styles like a man possessed, moving from more challenging solo ventures (1978’s Open Fire and its massively popular instrumental gem, Town Without Pity) to the secure structure of a four-piece band (à la Gamma), seemingly at will. But like many a sensitive creative soul, Montrose suffered crippling bouts of depression, ultimately (and quite sadly) culminating in the taking of his own life at age 64, in March 2012.

But with all the buzz surrounding 10x10 and the pair of reissues, the subject of Montrose’s legacy has moved back into the spotlight for a timely reassessment and reaffirmation.

Echoing Collen’s thoughts, Bonilla theorizes, “It may just take something like 10x10 to spur questions like, ‘Well, who is this Ronnie Montrose guy?’ It’ll all happen at the time it’s supposed to happen.”

The time for it to happen is clearly now, so with that in mind, Guitar World reached out to many of Ronnie’s friends and peers to have them tell firsthand tales about the man’s highest highs, along with some of his lowest lows.

Have you heard the news? There will always be some good rockin’ in store tonight whenever Ronnie Montrose is the one playing that guitar.

Edgar Winter

“When I put together the Edgar Winter Group in 1972, the whole idea was for it to be the quintessential all-American rock band – guys who were not just good musicians but all-stars in their own right, fully capable of fronting their own band.

“It was a huge talent search. We listened to a thousand demo tapes that were sent into the office. When we were looking for a guitar player, I wanted contrast and balance. Ronnie had played with Boz Scaggs and Van Morrison, and even before I met him, I said, ‘Well, he has to be good.’ And as soon as I saw him play – even the way he flung the guitar over his shoulder – I said, ‘Ohh! This is the guy.’

“What I most appreciate about Ronnie was his total commitment. He wasn’t a technical virtuoso – but neither was B.B. King, and he was the king of the blues. What Ronnie had was a virtuosity of the heart. And that rebellious edge of his? It was very spontaneous.”

Sammy Hagar

“We were thinking about calling ourselves Jupiter, and we were also thinking about White Dwarf. We’d be the biggest planet in the solar system! That’s what Montrose would have been called, if not for cooler heads. [laughs]

“Everybody else I’ve worked with, like Joe Satriani, Eddie Van Halen, and Neal Schon – they wrote the music, I listened to it, and then I’d write lyrics to it. When Ronnie and I used to write in Montrose in the Seventies, he would dig through my lyrics, and he’d write music to them. That’s what he did for Space Station #5, I Don’t Want It, Spaceage Sacrifice, The Dreamer – all of those different songs. I guess it was kind of like a Bernie Taupin/Elton John kind of thing, only with guitar instead of piano.

“The weirdest thing about Rock Candy is the tempo we had on the first take. I wonder how it got slowed down, because we didn’t know any better.

“When we were writing it and jamming on it, it was all bouncy, almost like a shuffle. But then, somehow in the studio – it might have been [producer] Ted Templeman, Ronnie, or anyone in there saying, ‘Slow it down.’ I don’t know how that happened, but it sure made a difference when that song was pulled back into the right tempo.

“And that should be a lesson for any young bands out there – find the right tempo for your song. The power of Rock Candy came when it was slowed down. When it wasn’t slowed down, it wasn’t as powerful.

“Denny Carmassi was capable of coming up with badass grooves like the one on Rock Candy and Ronnie was capable of coming up with badass riffs. I was capable of writing lyrics and coming up with the words and Bill Church was very capable on the bass.”

Marc Bonilla

“Everything Ronnie did, he did with his heart. Ronnie was definitely one of those guys who never subscribed to, ‘Let’s just play Rock Candy and get it over with.’ He never did that. He always pressed the envelope, probably much to his financial chagrin and his popularity, because you couldn’t put him in a box. He’d slither out like an octopus. He was always onto the next thing.

“Ronnie never traveled in a circle. He went in a straight line. He never repeated anything. After the Montrose stuff was over, he said, ‘That’s enough of that. I’m not doing vocals again. I’m doing instrumental stuff. Then I’m gonna do acoustic stuff.’

“But that’s what a real artist does. They go from one thing to another: ‘Okay, I’ve already done that. Let me try and push the envelope a different way.’ He was always pursuing a place where he was a little out of his comfort zone – which is where you should be as a musician. You should be out there on the water enough to where you don’t quite touch the sand. That’s a good place to keep your life.”

Dave Meniketti

“Ronnie was a big influence on me and the band when Y&T first got together [in 1974]. The classic first two Montrose albums and Gamma were like the standard for hard rock tunes in the Seventies – they were always on our record players. Pretty much every musician was playing one or more of these songs in their cover bands.

“Ronnie and I worked together on songwriting in the late Eighties. It was a cool experience to see how he came up with song ideas and arrangements. He had a knack for getting to the best bits of a song, and quickly.

Everyone always talked about his tone, and other players tried to use gear Ronnie used to try to emulate it. The truth was, his tone was in his hands

Ed Roth

“Like me, he was a gear nerd and a tweaker. He would do things like buy a console, completely disassemble it, and then replace the parts to make it better-sounding. He was always after something new and exciting to mess with. I loved that about him – the quest for better gear, and the constant search for interesting things on the horizon.”

Steve Lukather

“Ronnie was a star in his own right. A lot of people cite him as an influence and those early records as great Seventies rock and roll. You can go to those YouTube clips and see him playing his ass off, and it’s all for real! It’s all very real and raw.

“We did have a brief conversation years ago. When Ronnie called, we hit it off and there was talk of maybe doing something together, but it never came to fruition, for whatever reason. And when I got the call to do the solo on [Hagar’s] Color Blind for 10x10, I was very honored. I kept asking Sammy and Ricky, ‘Are you sure you want me to do this? There must be other guys!’ I was told, ‘No, Ronnie really liked your playing.’

“There are no tricks. I brought a little Kemper profiling amp, plugged in, and that was it. There were no effects; nothing. I was trying to play something with a little heart and soul; I wasn’t trying to be the fastest gun in the west. And I certainly wouldn’t try to play like Ronnie. That would be weird, because I respected him too much as a musician.

“I thought about Ronnie the entire time I was working on that solo, and everything that had happened with him. I’ve lost some close people in my life recently and it makes you become pretty emotional, to the point where you go, ‘Wow, this is some heavy stuff.’ I’m a very highly sensitive person, so those sorts of things really affect me.”

Ed Roth

“I had the good fortune to play all kinds of music with Ronnie, including his electric and acoustic instrumental music, and some of his soundtrack music. Whatever he wrote and produced, he wanted to try different and new things. Ronnie would always say he never wanted to be a nostalgia artist. His career is proof of that.

“As OCD as he could be about some things – like making sure each rack screw matched in his rig, spray-painting the faceplates of some of his gear black, making his own cables so the lengths and looks were the same – somehow, he wasn’t overly anal about his performances. He knew how to make you feel comfortable and recognized when you had the right take.

“He was great to work with in the studio, and knew when something had the vibe it needed. If something felt good, that was it, whether a clam snuck into the performance or not. If it had feel, Ronnie would go with it.

“Everyone always talked about his tone, and other players tried to use gear Ronnie used to try to emulate it. The truth was, his tone was in his hands. He used super-heavy strings, which also contributed to it. And he loved his Baker guitars, which he played from the time he got them until his death.

“Like all musicians, he had his ups and downs. Sometimes he would sell some of his gear and replace it with gear he was given by companies, so it would change. No matter what he used, he had a rich tone that was all his own. He played with conviction in a way that you felt every note.”

Hagar

“I’m really surprised Leaving the Warmth of the Womb, the track we did together for Marching to Mars [Hagar’s 1997 solo album] with Carmassi on drums and Church on bass, didn’t get a lot more attention. I was really excited: ‘Hey, it’s Montrose Montrose Montrose!’ I love that song. I thought it was very deep, and very cool. It’s a fucking killer track.

“I actually left the studio for a bit after I thought it was finished. I thought Ronnie had done a great solo on it. When I came back about three or four hours later, he had redone it. Originally, the solo didn’t go to the four, I believe, but Ronnie put another chord change in it, and he replayed the solo. When I heard that, it was fucking goosebumps city, man. It just had it.

“A few years later, we were talking about doing my 65th birthday in Cabo [Hagar's club in Mexico, in October 2012]. I was going to have Ronnie and everybody in Montrose come down. I was saying to him, ‘I want to bring everybody down there and take it to another level while we’re all still alive.’ That was always our big joke: ‘We gotta do it one more time.’

“I loved the fact that we were starting to groove again, and he and I were getting back together. I was really looking forward to that. I called him again to confirm it, and he told me he was committed to doing it. And then a month later, Carmassi gives me the call.

“It was so shocking. [slight pause] I thought Ronnie was tortured. Sometimes it was so difficult, but that was the last thing I ever thought Ronnie Montrose would do. No one knew he was like that – that he had that ability; that he was really that tormented. He was so private. I don’t know what he was protecting, but whatever it was, obviously, it tortured him enough to have him take his own life.

Ricky Phillips

“After Ronnie got prostate cancer, he didn’t pick up a guitar for two years. He went through a lot of stuff emotionally and physically, not to mention pain-wise. When he came out on the other side of that, he put a band together, started gigging, and he was playing so great.

“Hearing about his passing was shocking news, especially after how positive he seemed to be in the last conversation we ever had. Right up to that, he still wanted to finish 10x10. Every time I brought it up, Ronnie was really positive about working on it, as best he could.”

Leighsha Montrose

“Ronnie once told me his personal philosophy: ‘Listen – I don’t want to live my life like this,’ and he held his hand out flat. ‘I want to live my highest highs, and I want to live my lowest lows. I want to be in both, and savor both.’ And to say that – I mean, wow. That means you’re willing to feel the pain of the pain, and the joy of the joy – and he sure did.

“But you can’t define him by that one final day. He always found a way to make all of his interactions very personal, and he had that ability to make you feel like you were the only one in the room, even if it was the first time he had met you. I still feel there’s a piece of him that remains in all of us.”

Hagar

“I’m really glad Ricky Phillips took the initiative to finish 10x10, because it’s a nice little memory. It truly is Ronnie’s last work. It’s a cool project. And it’s always valuable to have something like this as a last work, rather than digging up some stuff from his past. This was something he truly had a vision for. There was always a special energy whenever I sang with Ronnie, and I’m still humbled by that experience.”

Ronnie Montrose

[In conversation with Ricky Phillips, explaining why he liked to leave most of his takes “as is”] “Let’s keep it real. Those aren’t mistakes. That’s life. That’s music breathing.”

This feature was originally published in the March 2018 issue of Guitar World.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![B.B. King [left] cups his hands to his ear as he asks the crowd for more. Joe Bonamassa, with a Les Paul, gives his crowd a thumbs up](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/P3XrQLh86C27JfPp4AGp6n.jpg)