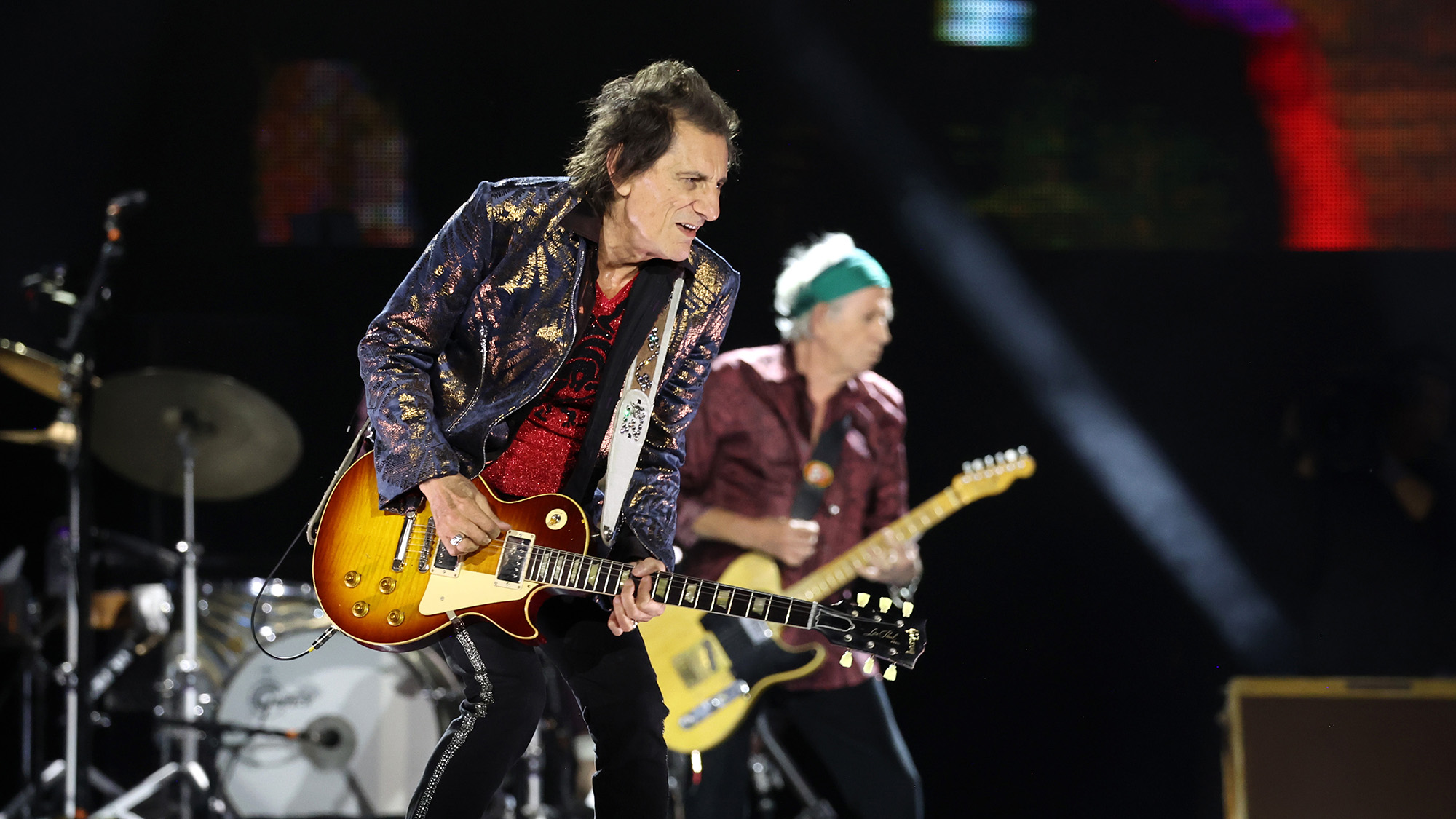

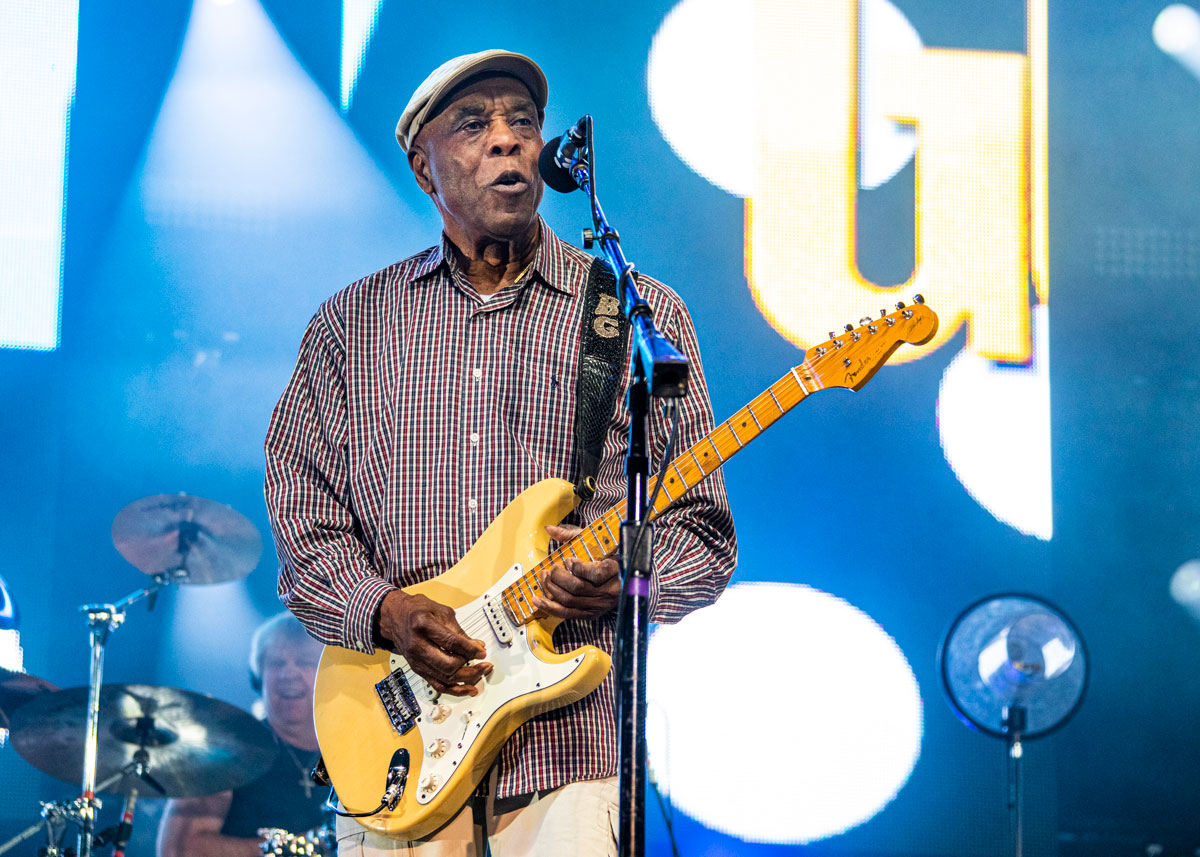

Buddy Guy: “When you pick up a guitar, you have something of your own even if you don’t realize it”

With a new documentary about the great Buddy Guy soon to air on PBS, we spoke to the world’s greatest living bluesman about a life bending those strings and chasing people’s blues away

When Buddy Guy speaks he's got the weight of history behind him. He has seen it all. The world’s greatest living bluesman turns 85 next week, and while he jokes that nowadays he’s less mobile onstage, there’s still plenty of sap left in his storytelling. He recalls all the details, from growing up in rural Louisiana to making his name onstage in the bright lights of Chicago.

There’s still plenty of magic in those fingers, too. Not that he’d have you believe it. There’s a braggadocio to playing the blues, working on your style so those stories come to life in front of an audience.

Guy, however, is reticent to talk about his abilities or his influence on the likes of Hendrix, Clapton, Bonamassa, and pretty much any blues or blues-rock player who has ever picked up the electric guitar. Not the way we can.

Maybe being humble gave him the edge. Maybe knowing – or at least believing – that there was alway someone better than him, made him appreciate that, no matter who you are, there is always more to learn with the instrument, and as he explains here, that could come from the horn player, the keys, anybody, and just at the point where your abilities end, that’s where showmanship can take over and give the audience something that they’ll never forget...

There’s a lot of talk about keeping the blues alive, and the charge is led by today’s generation of players, the Joe Bonamassa and Eric Gales generation, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram et al.

On the face of it, you could argue all this is unnecessary; rumors of the blues’ demise have been greatly exaggerated. The blues has shaped popular music as we know it. There’s a self-renewing quality to the blues that makes it eternal. After all, there is no generation, no demographic, not one soul on this planet who hasn’t had or got the blues.

But Buddy Guy’s worried. He’s old-school. He sees the lack of FM radio airplay as impeding the art-form’s progress.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As he joins us on the telephone, his warm voice crackling in a chuckle whenever he’s talking about BB King, or the trailblazers who came before him, he wants to underscore the point that, sure, we’ve all still got the blues, but someone has got to keep the music under the spotlight.

A recurring theme comes up with the documentary and your career of late and that is this idea of keeping the blues alive. There are a number of great younger players out – do you think the blues is safe now?

“No, it’s not in a healthy place, because we have satellite radio here, and they play blues, but the rest of the radio stations are hardly playing the blues. My son, when he was 21 years old, came in and saw me play, and changed his complete mind. He cried and said, ‘Dad, I didn’t know you could do that!’

“But if my records had been played on radio, once or twice a month, he would have known more about my music than he did.

“I don’t wanna go to my house and tell my son or your son, or anybody’s son, ‘You should do this.’ Because if they grow up and they fail then they’d look at me and say, ‘If it wouldn’t have been for you I wouldn’t have done this.’

“So I like everybody to listen and make up their own mind like I did.’ My Dad didn’t come to me and say, ‘I want you to be a musician.’ He looked at me and told me, ‘Whatever you do, don’t be the best in town, just be the best till the best come around.’”

I don’t think that I am the best guitar player ever, because I still listen to younger players than me

Speaking to some of the young players who you have taken under your wing over the years, like Quinn Sullivan, he specifically said that this was the lesson he took from playing with you – to always be 100 percent, all of the time.

“Well you gotta do what you gotta do, and be the best you can at whatever you do. If it’s riding a truck, y’know, you wanna be the best. And like I said, don’t be the best in town, just be the best till the best come around, and that goes for anything, not only just music.

“If you’re a doctor, be the best, or try to be the best. Music is the same. Like you said with blues music, it worries me now because it is not exposed like it used to be. Before we had all the big FM radio stations, we had AM stations, and they played gospel, jazz, blues or whatever record was out, they played.

“Now, these big stations play the same records all day, the same artists all day, and don’t give that young person a chance to be heard [so that] maybe one day he or her would be a big superstar.”

Did a sense of competition help your generation of blues players find their own styles and push themselves to be the best?

“Well, y’know, when you pick up a guitar – bass, drums, anything – if you have listened to other music, even if you are learning through a school, you have something of your own even if you don’t realize. And that’s what happened to me.

“People started telling me, ‘Man, you sound good!’ And I didn’t hear that. I kept saying to myself, ‘Man, you need to learn more. You need to listen to so-and-so.’

“Every time I would listen to a different guitar player I couldn’t be him, so I just said, ‘Let’s see, can I play what he played?’ In the meantime, I didn’t hear it but you’d be learning something by trying to learn something from somebody else.”

There’s something about playing the blues that’s a little like standup comedy; it’s like anyone who can land a decent joke or a story has got a fighting chance to be able to phrase something interesting on a guitar. Is that something you recognize in blues, that sense of having a conversation with the audience?

“People like Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, they got it so well, I don’t think they have to put on a show. But I have to, I have to do something to get your attention. Sometimes, I don’t think my notes is clean or clear.

“Some of the other guitar players, I have tried to learn licks from. But if I jump off the stage or run across it – of course, at my age, I can’t run across the stage no more, I walk across! [Laughs] – then these are some of the things I’d do to get people’s attention. ‘Watch me for a while and see if I can do something that’ll get a smile on your face.’ That’s my purpose, and hopefully I can stay out here another year or two and play the blues.”

“The late Guitar Slim, who made a big record called The Things That I Used to Do, he didn’t just stand there and play – he was a showman, and when I saw him play I said, ‘If I ever learn how to play I wanna act like him, but I would love to play like BB King.’”

You’re a very humble man. If anyone has got it, you’ve got it, and it speaks to everyone on the planet. I’ve been to little bars in Kyoto, Japan, where there are pictures of you all over the wall and a signed poster.

“Well, [laughs], another thing I was taught by my parents – every little bit helps! But, as I said, [it is] the exposure to airplay, to blues and not just Buddy Guy, but the greats, Muddy Waters and BB King.

I don’t have anything against the new music but I would just like the whole world to know that these great people dedicated their lives to playing music

“Radio stations should play them once or twice a month just to let you know what was there before all this new music came out. I don’t have anything against the new music but I would just like the whole world to know that these great people dedicated their lives to playing music.

“Some of them just played it for the love of music; they didn’t even make a decent living out of it. I got a chance to meet some of them, like [Mississippi] Fred McDowell, Son House, Lightnin’ Slim – the first electric guitar I ever seen in my life – and they didn’t make a decent living but they had fun playing.

“They played for the smile of music, a good drink of whiskey, and if you played good enough you got a good lookin’ girlfriend!”

That’s living the dream. When you arrived in Chicago, coming from the country, did the energy of the city change your style, make you that bit louder, more electric?

“Well first of all, I didn’t think I was going to join this crowd here, because when I came, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, you had Sonny Boy Williamson, Jimmy Rogers and all those guys were making hit records at Chess Records.

“You had the jazz guys… We was listening to everything! But I said, ‘Buddy, you in Chicago but sit back, listen and learn. Don’t rush out there and think you can join these guys, just sit back and hope you can learn something from them.’ And I learned a lot from them.

“Before they passed away, I guess I had learned enough to get a chance to meet them, ‘cos I wouldn’t have met them by just saying, ‘I’m Buddy from Louisiana.’ I had to learn how to play a good lick on the guitar, and every once or a while I’d be in a little blues club, hoping somebody would hear me playing, and I’d look out and there was Little Walter watching me.

“I looked out there one night and there was BB King. I said, ‘Oh my God.’ I didn’t have a record. I was playing B.B. King, trying to play B.B. King, and when I took a break I tried to avoid him. But he called [on] me and we were friends until he passed away.”

Were those Chicago blues crowds intimidating back then?

“No, I had played a few little blues clubs in Baton Rouge and Mississippi and there weren’t many big blues clubs in Chicago. When you first started, you wouldn’t get into those. No way. It was just a little blues club that held 40 or 50 people.

“Otis Rush was the first one who gave me a chance to come up and play onstage, and I said, ‘I can’t play as well as Otis or Magic Sam.’ A lot of blues musicians had music stands and I thought he was reading music, and I come to find out later on they weren’t. They just had it onstage to show off or something.

“I said, ‘Well, I can’t read so I’ll forget about that!’ But some of them were sitting onstage and playing. I said, ‘I wanna do it like Guitar Slim or BB King. I’m gonna stand up and jump off this.’ Most stages were behind the bar, and I said, ‘I’m going to jump off this bar.’ And that got their attention. They started calling me the Little Wild Man from Louisiana. I got attention from doing that.”

Is that why you moved from using Guilds to the Strats?

“I came here with a solidbody because if you played like I played and you dropped the Guild it’d bust and break. The solidbody would take it. I accidentally dropped my guitar and found out the solid guitar could take a fall, I stuck with it and still with it.”

The price of the guitar skyrocketed when BB King made Three O’Clock Blues

You’ve jammed with so many of the greats. Who would be your favorite to playing alongside?

“Oh I can’t… I love ‘em all! But BB King is my favorite, man, ‘cos he’s the one that bent the strings on those guitars. I told him when he was in his good health, when I met him, I said, ‘Man, you’re the best I’ve ever seen. But I got something I dislike about you.’ He said, ‘What’s that!?’ I said, ‘Used to be the guitar was a reasonable price, but when you came up with Three O’Clock Blues you put the guitar out my reach!’ The price of the guitar skyrocketed when he made Three O’Clock Blues.”

Reading your biography, about how you could break in a wild horse, there’s kind of something similar going on with the electric guitar, because there’s a lot of volume, there’s a lot of taming that needs to be done.

“I think that helped me when I got here because when I first came here the Chess people were saying, ‘That’s noise. Don’t nobody wanna hear that!’ But when I finally went to England in 1965, I don’t think Eric was famous. Jeff Beck wasn’t famous. Jimmy Page wasn’t famous, but when they got famous, years later, and I got a chance to met ‘em, each one of them told me, ‘I didn’t know a Strat could play the blues like you do.’

“And all them started buying Strats. They didn’t know a Strat could play blues. They thought it was for, like, a country and western, Roy Orbison-type thing, or for all the guys out of Nashville.

“But even Nashville got blues museums now. And Texas! I never thought I would go to Texas and Nashville; I thought blues cities were like Chicago, Detroit, places like that, but it turned out that Stratocaster turned a lot of people onto bending them strings like BB King.”

Some of the best blues albums have been live recordings. Do you feel more at home on the stage than in the studio?

“Well I can look in their faces. I can look in their faces and, if they are enjoying it, I can say to myself, ‘You must be doing something right. Keep doing it!’ [Laughs] So, don’t go trying to experiment with something else – if you’ve got them going, keep ‘em going!

“Like I say, I don’t think that I am the best guitar player ever, because I still listen to younger players than me, I listen to older players – and there ain’t many of them left now. That’s how I got my experience.”

Sure, you’ve got to listen to as much music as you can. There are lessons in everybody’s playing.

“I also listened to good keyboard players, ‘cos I try to steal something from the keyboard… The horn, they’ve all got something. I guess that is what helped me a lot because I didn’t just listen to one guitar player.

“If a horn player had a good lick, I’d say, ‘I wish I could play that on a guitar.’ And I would go try to find it – on my way trying to find it, it was like I lost a dime, and I was looking for my dime and I found a quarter.”

That’s it. The journey is the destination. You talk about those British players like Clapton. A lot of what made them what they were was that same journey, researching blues history and building on it. They referenced the blues heavily, but returned the favor in some ways by spreading the gospel.

“They helped all of us in America. Black people looked bonded to a certain amount of music. And I don’t bite my tongue, I think a lot of whites here in America didn’t want their children to hear blues, but when the British guys started playing the blues and started coming here…

“We had a television show in the '60s called Shindig. And the Rolling Stones were getting so big. They were taking over the world with music. And the television wanted to bring them on Shindig, and Mick Jagger said, ‘I’ll come if you let me bring Muddy Waters.’ And they said, ‘Who the hell is that?’ Jagger said, ‘You mean to tell me you don’t know who Muddy Waters is. We named ourselves after his famous record, Rollin’ Stone.

“The blues was being kept from a lot of white kids, and finally the colleges started listening to blues, to Lightnin' Hopkins, and Arthur Crudup, and a lot of those old blues.

“Because Lightnin' Hopkins and a lot of old guys like that were playing acoustic guitars, and as I said, BB King came out bending those strings, him and T-Bone [Walker], and that’s when the British started coming out here and America woke up. ‘Oh the British are bringing the blues…’ No, now, wait a minute. You had that already, you just didn’t know you had it.”

- Buddy Guy: The Blues Chase The Blues Away airs on PBS on July 27, 9pm EST.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.