Eddie Van Halen 1955-2020: a visionary virtuoso who rewrote the rules of electric guitar

An all-star line-up remembers the life, times and exploits of the player who raised the bar and reinvented the electric guitar

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some rock-star deaths hit like a sledgehammer. On 6 October, as the black news ripped through social media, fans both illustrious and unknown found a thousand ways to echo the same sentiment. Not Eddie Van Halen.

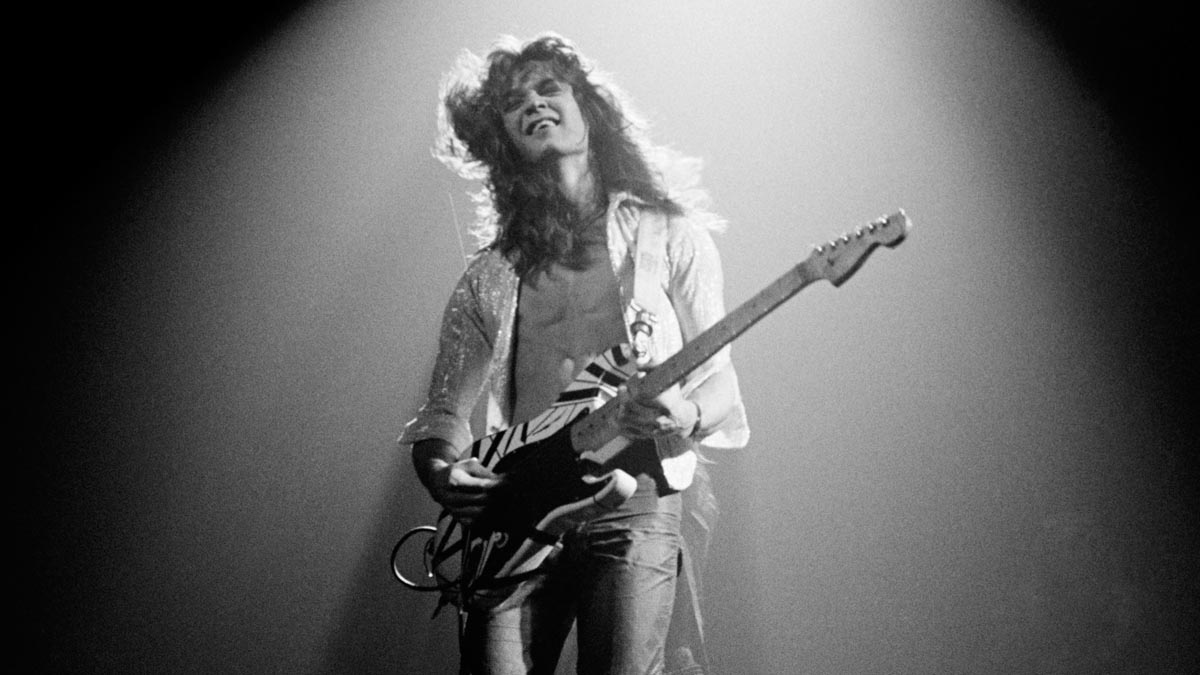

Death was so diametrically opposed to the life force in the Californian virtuoso’s fretwork. The black-and-white valedictory photos filling news feeds so drab compared with his kaleidoscope of DIY SuperStrats. The past tense of the eulogies so jarring when applied to the man who announced the future when he arrived in 1978, all megawatt smile and hands ablaze.

I was instantly mesmerised by the sound. In that moment, Eddie captured my heart with his musicianship. He expressed his joy of music in every note he played

Joe Satriani

“Eruption erupted through my radio as I was warming up on my guitar,” remembers Joe Satriani of the instrumental that marked the boldest line in the sand since Jimi Hendrix detonated the Bag O’ Nails nightclub in 1966. “I was instantly mesmerised by the sound. In that moment, Eddie captured my heart with his musicianship. He expressed his joy of music in every note he played.”

Article continues belowIn modern times, virtuoso players are 10-a-penny, Eruption a rite of passage. But it’s a hard thing to convey the impact of hearing the second track from Van Halen’s self-titled debut album back in 1978.

There had been wizards, speedsters and sonic adventurers before – from Jimi’s outer-reaches space blues, to Clapton’s precocious strut on Hideaway, to Alvin Lee hitting what seemed like the redline with I’m Going Home at the Woodstock festival. But with Eruption, Van Halen left them all standing.

He basically came in and laid waste to the competition. I’m just glad I was alive to witness it

Joe Bonamassa

“He basically came in and laid waste to the competition,” says Joe Bonamassa, “while changing the game like no-one since Hendrix. I’m just glad I was alive to witness it.”

Eruption clocked in at under two minutes; the average pop single lasted longer. But that was enough to run the gamut, fusing violent whammy abuse, breakneck rat-a-tat picking and – the pièce de résistance – a two-hand tapping kiss-off that seemed beyond human physiology.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He was a keyboard player, first of all,” points out Steve Hackett, “and he talked about the keyboard developing his finger strength. So he was applying that to the tapping technique, turning the guitar fretboard into a keyboard. A tapper el supremo. And then there were the machine-gunning effects, interspersed by motorbike noises. He was just so full of surprises.”

A piano prodigy from the age of six, who threw rogue notes into early Bach recitals, it’s diverting to imagine what Van Halen might have achieved had he heeded his father’s nudges towards the classical world.

But the smart money says that it wouldn’t have come close to the swathe he cut through the rulebook and world order of electric guitar. “He raised the bar higher than anyone ever had before,” considers Mark Tremonti of Alter Bridge. “He introduced the guitar world to more tricks and techniques than any other player that I can think of.”

I think I got the idea of tapping from watching Jimmy Page do his Heartbreaker solo in 1971. I just kind of took it and ran with it

Eddie Van Halen

For a revolutionary, Van Halen’s influences were traditional. Despite his image as the quintessential West Coast shredder, Eddie and his older brother Alex arrived in California from the Netherlands in 1962, with a mere $50 to the family’s name – but just in time for the British Invasion.

“I remember hearing Jimmy Page when a friend brought over the first Zeppelin album,” said Eddie. “I completely tripped on it. I might have gotten into Cream, then dug back to find the Bluesbreakers. I was developing technique in a fun way.”

From those unremarkable touchstones, Van Halen forged a technique like no other (“I think I got the idea of tapping from watching Jimmy Page do his Heartbreaker solo in 1971,” he told Guitar World. “I just kind of took it and ran with it”). But unlike the cliché of the closeted and obsessed shredder, the bedroom would not be Eddie’s milieu for long.

In 1972, the brothers co-founded Van Halen and hit the West Coast circuit like a train, the de facto leaders of a line-up completed by charisma-bomb singer David Lee Roth and steady-groove bassist Michael Anthony. Already, Eddie’s dizzying prowess was pulling in fanboys and would-be plagiarists: he took to performing solos with his back to the audience, the better to conceal his bag of tricks.

I remember hearing Eruption in seventh grade while playing Wiffle ball with my little brother. Time stood still. It was as if I was hearing something that had been created light years away by some alien life force

Myles Kennedy

But with the Van Halen album released on Warner Brothers in 1978, the tap was out of the bag. “I remember hearing Eruption in seventh grade while playing Wiffle ball with my little brother,” says Alter Bridge’s Myles Kennedy. “Time stood still. I just stopped dead in my tracks and stared at the boom-box, asking myself, ‘How is this even possible?’ It was as if I was hearing something that had been created light years away by some alien life force.”

Among guitarists, it became shorthand for his brilliance, but Eruption wasn’t the extent of Eddie’s game-changing gifts. Elsewhere on that debut album, he announced his other talents, from the melodic instincts of Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love (an arpeggiated riff so basic he almost never presented it to the band) to the often-overlooked rhythm chops that underpinned the stalking groove of Jamie’s Cryin’. “His sense of rhythm was so attractive and seductive,” reflects Satriani. “He made everything swing in just the right way.”

For all his flair on record, Eddie might not have lit the touchpaper had he been a dour figure like the presiding wizards of prog, feet rooted to the stage, eyes locked on the fingerboard.

With the band now into the charts and filling major venues, a generation of fans were struck by the infectious exuberance of Eddie’s live presence: a twirling, whirling, joyous man-child who made those blur-fingered flights look like a kid thrashing a tennis racket.

“Part of the allure was the fact that he made his musical prowess look easy and fun,” agrees Kennedy. “It was that smile and wink of the eye that enticed you not only to listen but dared you to follow in his footsteps.”

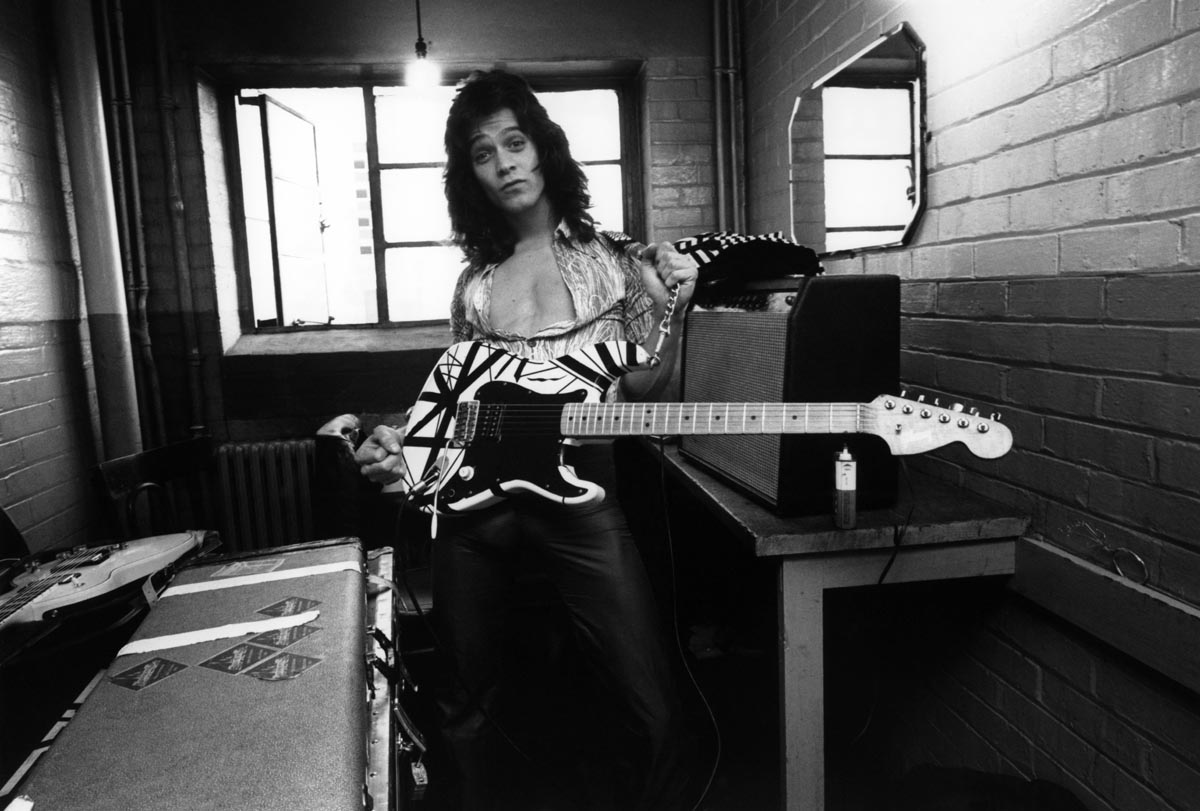

And while the fretboard pyrotechnics hooked you, the gear was almost as eye-popping. By the late 70s, modding had entered the lexicon, with Brian May toting his homemade Red Special across the world’s stadia.

But nobody took it further than EVH, whose original ‘Frankenstrat’ electric fused a “junky piece of shit” Boogie body, an $80 neck refitted with Gibson frets, a much-punished tremolo unit and a single bridge pickup.

“It sounded like a cross between Gibson and Fender, a humbucking tone with a vibrato,” he remembered. “I wanted to just fall off the edge of buildings with this guitar and when I first played it, I thought, ‘You can’t buy one of these anywhere.’ I felt like I was onto something, and obviously I was.”

“Our generation of players were a bit frustrated with the chasm between Fender and Gibson designs,” recalls Satch of the ensuing SuperStrat boom. “So I was not surprised to see Eddie come up with a few hybrids.”

There’s an argument that Eddie’s tidal-wave influence came at a cost. For every future guitar hero who left the blocks in thrall to his sound and ready to add their own stamp, there were slews of shred clones bringing nothing new to the table but an extra lick of speed.

“I think that in America, the MI school then brought out a generation of guitarists who were all trying to be like that,” says Hackett. “It’s a little bit like treating music as sport, where you’re shaving nanoseconds off the other guys’ technique.”

Unlike the chasing pack, however, the man who started the big bang was no one-trick pony, expanding his palette across Van Halen’s catalogue with moments like the warp-speed flamenco shred of Spanish Fly, from 1979’s Van Halen II, and the skittering Mean Street intro lick that opens up 1981’s Fair Warning.

“I tapped on the 12th fret of the low E and the 12th fret of the high E, and muffled both with my left hand by the nut,” explained Eddie of the latter. “I got kind of a funk slap out of the guitar, like a bass player.”

And if Eddie was already a talisman on the guitar scene, then a brace of crossover hits in the early 80s thrust him into the consciousness of fans who hadn’t even heard of a Floyd Rose tremolo.

A highlight of Michael Jackson’s all-conquering Thriller album, 1983’s Beat It opened with a moody riff courtesy of Toto’s session ace, Steve Lukather. But the track achieved lift-off when Eddie’s solo revved into the mix and down the antennae of mainstream pop fans, setting a high bar for Jacko’s live guitarist, Jennifer Batten.

“That was the solo that bought me a house and launched my career,” she told us. “I got a chance to play it for Eddie one time, which if I’d known in advance, I probably would’ve screamed and run the other way. Afterwards, he grabbed the guitar off me and he wanted me to remind him how it went.

“It was fascinating, because even though I was playing the same notes, there were certain passages he played in a different way. There was one passage where he does a super-big stretch that I can’t do, so I worked around it with tapping. I’m really glad I got to meet him. He certainly meant a lot to me, and pretty much every guitar player on the planet.”

I put 1984 in the same category as Powerage and Sheer Heart Attack in that there is not a single skippable track on there

Justin Hawkins

Just as inescapable, Jump’s instant-classic synth hook drove the song to US No 1, made parent album 1984 the band’s joint best-selling release (alongside their debut album), and reminded us that EVH was a rare shredder who put the song first.

“His impact was not confined solely to the mastery of guitar,” explains Mark Morton of Lamb Of God. “As a songwriter, Edward’s pop sensibility and songcraft propelled his band through decades of worldwide chart-topping success.” Even if the keys were front and centre, Jump still made room for a spring-heeled guitar solo.

“I first consciously heard Eddie Van Halen at DJ Geoff Lightfoot’s Rock Night at the Fighting Cocks in Lowestoft,” says Justin Hawkins of The Darkness. “He played Jump, as you would expect, and I’ve loved Van Halen ever since. I can’t play anything like EVH, but his attitude toward the guitar and the movements within his solos are a constant source of inspiration.

“I put 1984 in the same category as Powerage and Sheer Heart Attack in that there is not a single skippable track on there.” Post-1984, even the swap-in of frontman Sammy Hagar for Roth didn’t slow Van Halen’s sales: so long as Eddie was present and correct, reasoned the fans, all was well.

Yet the EVH story is not one of an unbroken ascent, nor the scissor-kicking early shots of a young rock star in love with life and music the full story.

A smoker and drinker from the age of 12, the guitarist deemed himself a “functioning alcoholic” until 2008, and at times he stretched that definition to breaking point. There were tales of late, sloppy performances at trade shows, and mixed reviews for the 2004 reunion tour of which Hagar told this writer, “he probably doesn’t remember nine-10ths of the shit he did”.

Eddie had already been visited by cancer, the guitarist blaming the metal picks he clamped in his mouth, combined with a studio buzzing with electromagnetic energy, for the partial removal of his tongue in the early post-millennium. It was that same disease that killed him, the guitarist passing away at Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, following a five-year battle with throat cancer. He was 65 years old.

You didn’t have to be a shredder or speed-freak to mourn the loss of Eddie Van Halen. The love and respect across social media felt as universal as any guitar-hero death to occur in the online era: a genre and generation-crossing deluge that underlined just how far and wide his ripples of influence have spread. Those game-changing fingers may have fallen silent, but the legacy will keep erupting, from here to eternity.

“Frank Zappa once said that Eddie Van Halen reinvented the guitar,” considers Ritchie Blackmore. “I agree. He will be sadly missed, but his brilliant legacy will always be remembered. The ultimate guitar hero…”

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.