“I knew exactly what I wanted to do in every respect”: How Jimmy Page built Led Zeppelin from the ashes of the Yardbirds

Using knowledge gleaned from his time as a first-call session pro – and his brief but crucial tenure alongside Jeff Beck in the Yardbirds – Page formed a rock colossus from the ground up

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This feature on the launch and ascent of Led Zeppelin was originally published in the March 2009 issue of Guitar World.

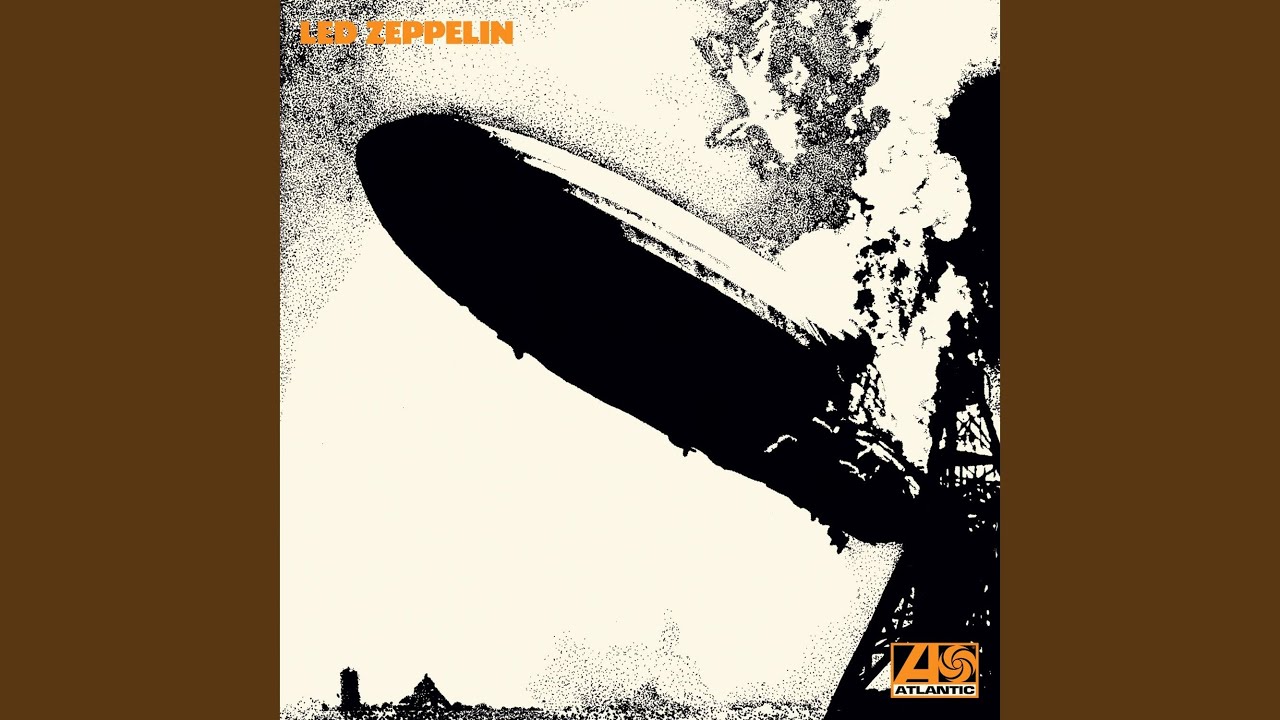

It's been over 40 years since the U.S. release of the first Led Zeppelin album on January 12, 1969, but the record’s influence continues to be felt profoundly. Titled simply Led Zeppelin, the disc marked a pivotal moment in rock and roll culture, where the pop-oriented rock and roll of the Sixties started to give way to what would become the heavier-sounding, artist-driven orchestrations of early Seventies rock.

As our present notion of classic rock derives from the Seventies FM rock-radio programming format, the first Led Zeppelin album is also a cornerstone of the classic rock canon. Beyond this, it is one of the seminal heavy metal albums of all time.

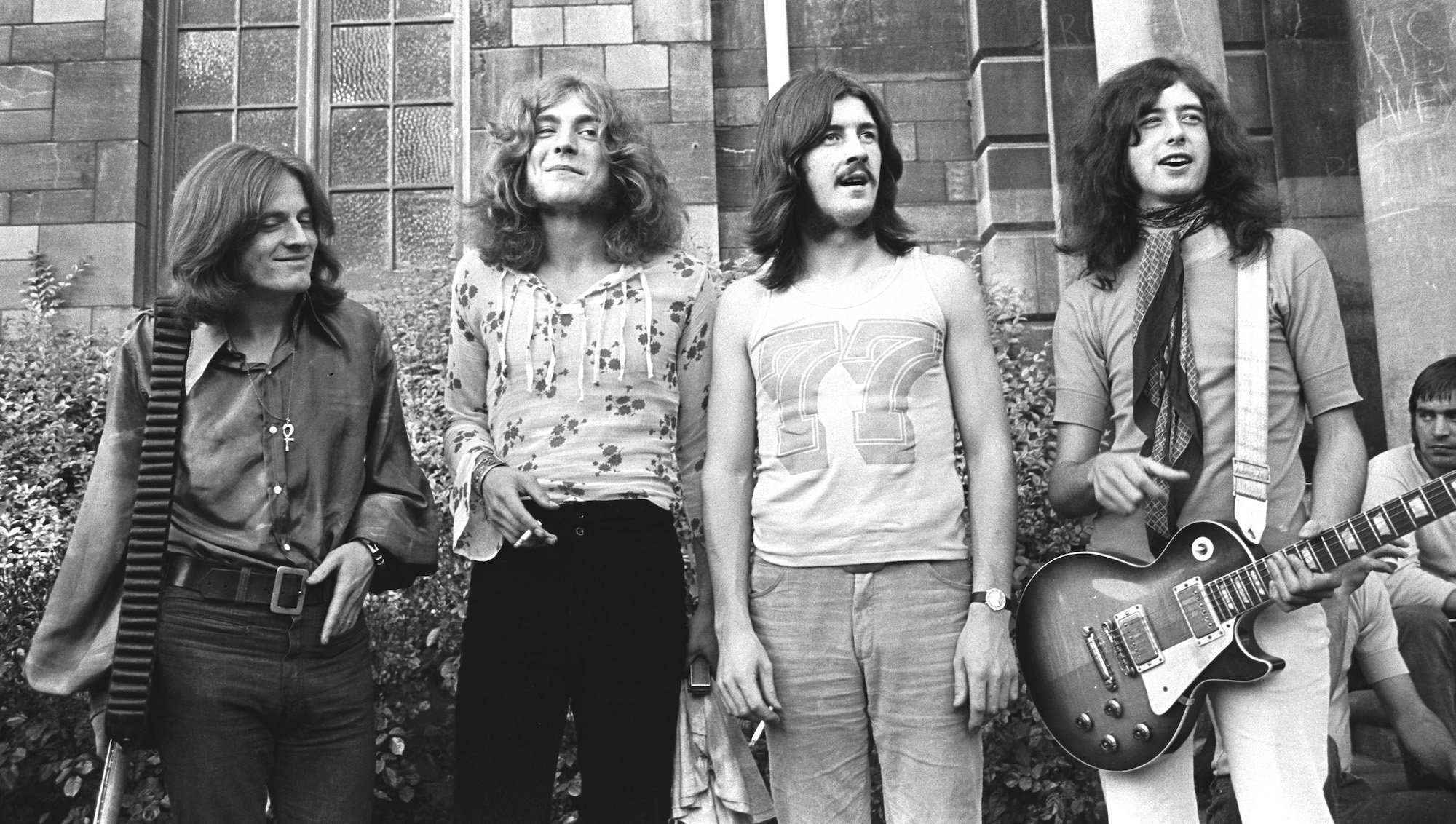

Indeed, it’s safe to say that metal probably never would have come into existence had Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones and John Bonham not walked into London’s Olympic Studios in the autumn of 1968 and laid down the nine hard-hitting tracks that became Led Zeppelin.

Several generations of rock guitarists have assayed Led Zeppelin classics like Good Times Bad Times, Dazed and Confused and Communication Breakdown in bedrooms, garages, and bars around the world. If you’re a rock guitar player, those licks are part of your DNA, whether or not you’ve ever played them.

The first Led Zeppelin album, however, didn’t spring into existence from nothing. It is very much the outcome of musical and production ideas that Jimmy Page had formulated with his previous band, the Yardbirds. Indeed, when Page, Plant, Jones, and Bonham were in the studio recording the disc, they were planning to call themselves the New Yardbirds.

These days, the Yardbirds are perhaps not as well known as Led Zeppelin, but in their time, they were the ultimate guitar band. How could they be otherwise, with Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page passing through their ranks between 1963 and ’68?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“They were a great band,“ Page says. “I was never ashamed of playing in the Yardbirds.“

The story of his alchemy in transforming the Yardbirds into Led Zeppelin is an archetypal rock narrative, filled with backroom deals and sheer brilliance wrested from rock and roll mayhem. It is also very much the story of two adolescent friends, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page.

“Jimmy and I have known one another since we were 14 or so,“ Beck says. “My sister gave me the introduction. She went to the same art college [as Jimmy]. And she came home and said, ‘There’s a guy with a goofy guitar like yours at college.’ And I went, ‘Where is he? Take me to him!’ ’Cause there was nobody else in my block or even in my town who even knew what a Fender Strat was. So meeting Jimmy was great – like meeting your long-lost brother. And we’ve got on well ever since.“

Both friends set out to make their mark in rock and roll. Page succeeded first, becoming one of London’s most sought-after studio guitarists. The British Invasion was in full force, and young Jimmy Page went to work for many of the top producers of the day, including Shel Talmy (who produced the Kinks and the Who, among others) and Mickie Most (who racked up major hits with the Animals, Herman’s Hermits, and others).

“My session work was invaluable,“ Page says. “At one point I was playing at least three sessions a day, six days a week. And I rarely ever knew in advance what I was going to be playing. The studio discipline was great. They’d just count the song off, and you couldn’t make any mistakes. I learned things even on my worst sessions. And believe me, I played on some horrendous things.“

In 1965, Page received an offer from the Yardbirds’ manager, Giorgio Gomelsky, to replace Eric Clapton, who was leaving the group. The Yardbirds had just scored their first chart-topping hit, For Your Love. Page, however, was doing far too well as a session musician and calculated that he could actually make more money that way than he could as a member of a hit-making group. Instead, he recommended his old friend Jeff Beck for the gig.

Jeff’s time with the Yardbirds was the most groundbreaking era for that band. It grew by leaps and bounds, really

Jimmy Page

Beck became the Yardbirds’ lead guitar player during the group’s golden period, from 1965 through ’66, racking up hits like Heart Full of Soul, Evil Hearted You, I’m a Man, and Shapes of Things, recordings that managed to be both innovative and commercially successful.

With Beck onboard, the guitar solos in Yardbirds songs started to become set pieces in and of themselves, a common practice today, but something that was unheard of until the Yardbirds came along. The group introduced the idea of mid-song tempo shifts, breaking into amphetamine-paced double-time segments or raunchy syncopations for solos, choruses, or bridges.

The Yardbirds became closely associated with a move called the “rave up,“ which basically involved jettisoning the song’s main chord progression and resolving to the tonic root for a solo or outro, building head-rush crescendos off this simple harmonic base.

Yardbirds’ bassist Paul Samwell-Smith and drummer Jim McCarty excelled at this kind of quick-witted rhythmic change-up. The idea of using rhythmic shifts to create episodic song structures would be a key Yardbirds legacy that Jimmy Page would invest in the creation of Led Zeppelin.

“Jeff’s time with the Yardbirds was the most groundbreaking era for that band,“ Page says. “It grew by leaps and bounds, really.“

Beck's lead guitar work with the Yardbirds helped create a vogue for minor-key improvisation based loosely on scales used in Indian classical music. (He was actually a few months ahead of the Beatles’ George Harrison getting this kind of sound onto disc.)

Beck excelled at employing distortion, sustain and feedback to simulate the resonant drone of Indian instruments like the sitar, sarod, and tamboura. At the same time, his playing remained firmly rooted in the blues. This potent combination was another Yardbirds legacy that Page would bring into Led Zeppelin.

Along with Beck, Samwell-Smith and McCarty, the Yardbirds’ lineup included the solid, if unspectacular, rhythm guitarist Chris Dreja and singer Keith Relf, whose vocal range was somewhat limited, but who blew a mean blues harp.

A lack of competent management was another challenge the Yardbirds faced. Their string of hit singles came at the price of punishing “package tours“ into the wilds of America and overly hasty recording sessions.

Samwell-Smith tried to improve the situation by assuming more control and formed an alliance with the Yardbirds’ second manager, Simon Napier-Bell, who had taken over from Gomelsky. Together, they produced some of the band’s best tracks, and Samwell-Smith discovered a vocation for production that would serve him for years to come.

The only way I could get Jimmy involved in the Yardbirds was by insisting that it would be okay for him to take over on bass... Within a week, we were talking about doing dueling guitar leads

Jeff Beck

The idea of record production by an actual band member was still pretty novel in 1965. Nobody produced their own records back then, not even the Beatles, Stones, or Dylan.

In that respect, Samwell-Smith’s move into coproduction helped smooth the way for Page’s full assumption of production duties on the first Led Zeppelin album a few years later. Even with increased artistic control, however, Samwell-Smith continued to grow discontented with the Yardbirds, and he left the group in mid-1966. Jeff Beck was quick to recommend his old friend Jimmy Page as a replacement.

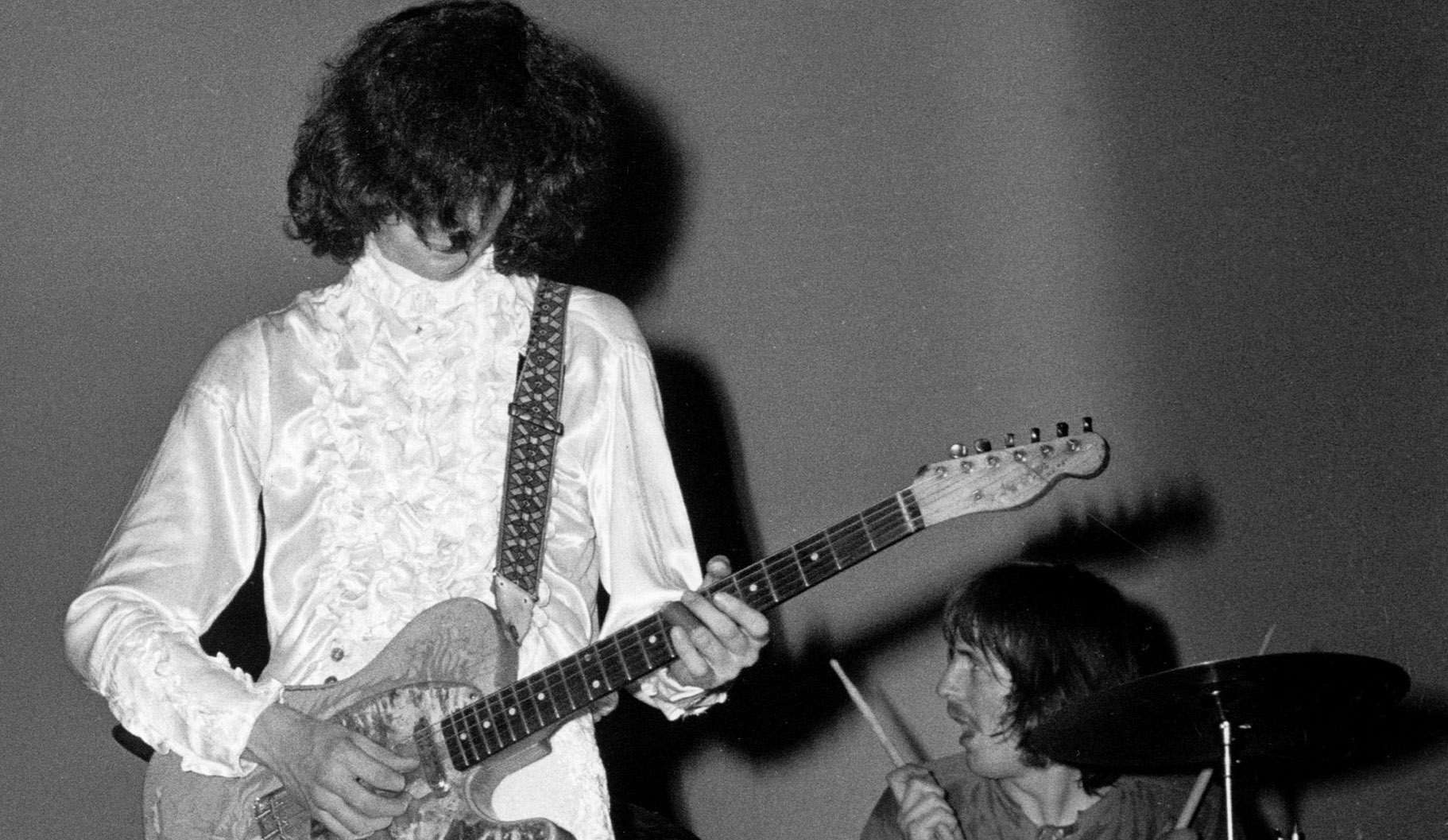

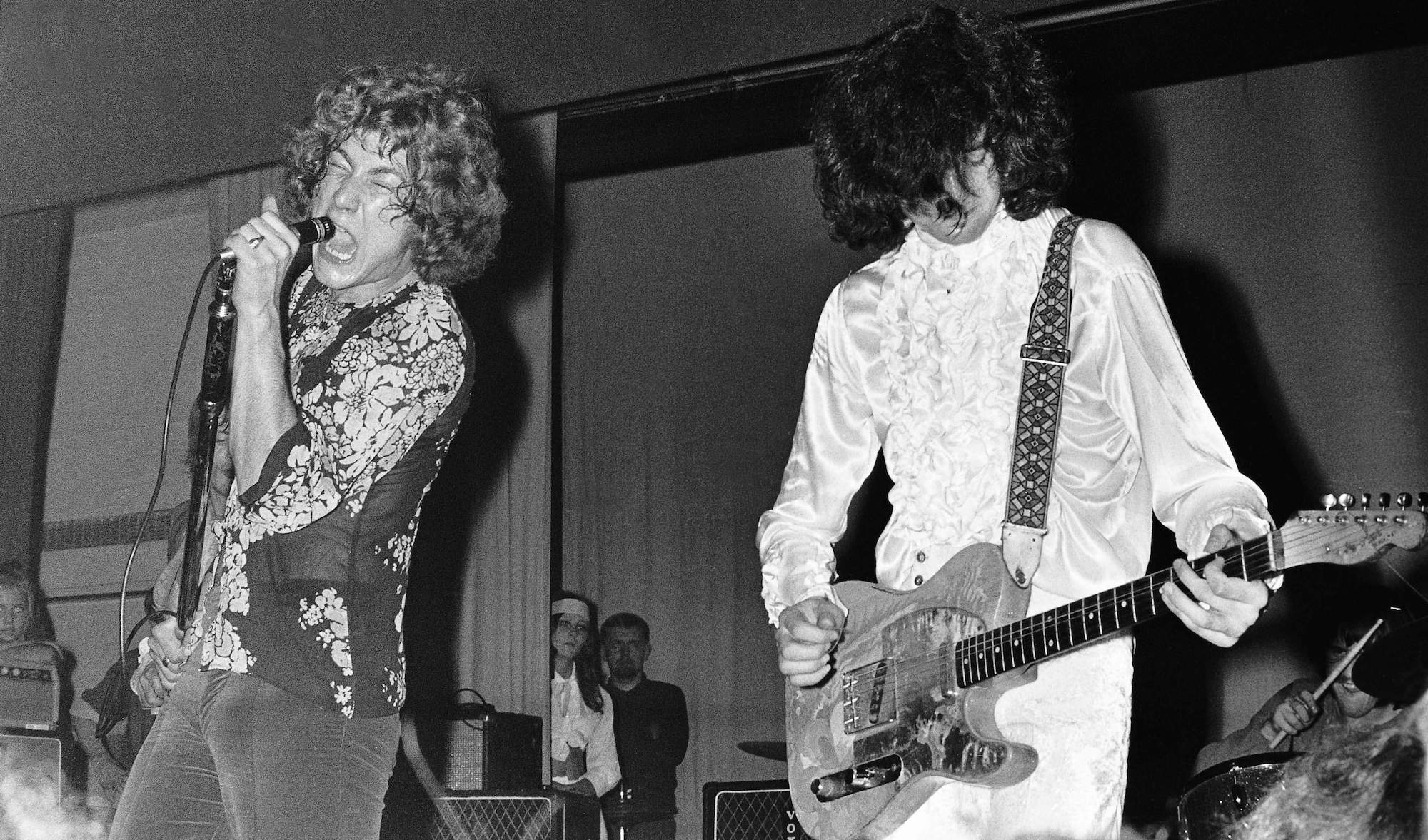

“Jimmy was not a bass player, as we all know,“ Beck says. “But the only way I could get him involved was by insisting that it would be okay for him to take over on bass, in order for the band to continue. And gradually – within a week, I think – we were talking about doing dueling guitar leads. And then we switched Chris Dreja onto bass in order to get Jimmy on guitar.“

By this point, Page was more eager to join the Yardbirds than he had been in 1965. While session guitar playing was certainly profitable, the hackwork element that went with the job had begun to take its toll.

“I finally called it quits after I started getting calls to do Muzak [easy-listening 'elevator music'],” Page recalls. “I decided I couldn’t live that life anymore, it was getting too silly. I guess it was destiny that, a few weeks after quitting doing sessions, Paul Samwell-Smith left the Yardbirds, and I was able to take his place.”

His first recording with the Yardbirds was Happenings Ten Years Time Ago, made in September 1966. This tour de force track ranks among the greatest in the rock canon, a moody slice of psychedelia with nightmarish overtones. John Paul Jones, at the time a top London studio musician, was drafted to play bass on the track, which makes Happenings a key Led Zeppelin precursor.

The Beck/Page Yardbirds lineup lasted for only a handful of live dates. There is no recorded document of these performances, but those who were there report amazing feats of harmonized and unison guitar leads, not to mention tandem soloing. “It could be brilliant with Jeff and Jimmy,” Jim McCarty recalls, “but it got a bit messy sometimes. A bit too much going on.”

“Obviously the two-guitar thing with Jimmy was a great idea,” Beck says. “But it was also fraught with disaster, because sooner or later one of us would have been cramped, stylewise.”

As it turned out, things never reached that point. Two dates into a particularly grueling package tour of America in October 1966, Beck became Page’s vehicle for formulating much of the sound and approach that he would employ in the creation of Led Zeppelin, not to mention the swaggering onstage persona that would set a new style for rock guitar performance. But back in England, there was plenty of business to transact.

With the Yardbirds rapidly unraveling, Simon Napier-Bell also jumped ship, selling his managerial interest in the group to Peter Grant in January 1967. An imposing figure of a man, Grant was partnered with the aforementioned producer Mickie Most in an organization called RAK Management and Production.

Back in those days, management and production were very closely allied. Early recordings by the Rolling Stones and Who had actually been produced by their managers at the time. But having no flair for production, Grant needed Most’s studio expertise. And so it was arranged that Grant and Most would take on the Yardbirds and also launch a career for Jeff Beck as a solo artist.

Having worked with Most in his session days, Page was perhaps more aware than anyone else that Most was hardly the ideal producer for the Yardbirds. An old school 'hit factory' guy and master of the three-minute pop single idiom, Most was great at making something of nonentities like Herman’s Hermits, but he was hardly the ideal man for an evolving, experimental guitar rock group. At the time, however, the Yardbirds didn’t have much choice.

Their career had starting going off the rails right at a time when a dramatic shift was taking place in the way rock music was perceived, consumed, conceptualized and created. Around 1965, youth culture split into two factions of music fans: those who were content to hear hit songs on the radio and purchase hit singles, and those who wanted to dig deeper and buy albums by their favorite groups.

Rock musicians, meanwhile, began to view album tracks not as mere “filler” but rather an opportunity for musical exploration outside the bounds of commercial radio accessibility. And so a culture of fans began to form around tracks like the 11-minute Going Home from the Rolling Stones’ 1966 Aftermath album, Bob Dylan’s 11-minute opus Desolation Row from 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited and the Byrds’ Eight Miles High from their 1966 Third Dimension disc. The Yardbirds’ mid-Sixties guitar rave-ups also slotted very nicely into this growing rock culture.

As 1967 dawned, this underground culture was poised to go global as the hippie movement. The first freeform FM music stations began to appear in America’s coastal major cities, playing not only ambitious rock album cuts but also free jazz, avant-garde electronic music, Indian ragas, poetry readings… you name it. Touring America with the Yardbirds, Page was able to witness this phenomenon first hand.

“The Yardbirds were probably more popular in the U.S. than in Britain,” he says of this time period.

“We had toured there extensively, and that experience allowed me to get in touch with the evolving tastes of the American market. There was a whole other underground scene happening that didn’t care about hit singles. In the late Sixties, American FM radio was very free form and would play entire sides of albums, including the more experimental music of bands like the Yardbirds, Cream, and Traffic.”

But this was a trick that old-school guys like Mickie Most had completely missed. His ideas on how to revive the Yardbirds’ flagging career were very much at odds with Page’s vision for the group, a vision much more attuned to where electric guitar-driven rock was heading in the late Sixties.

Page and his fellow Yardbirds entered De Lane Lea studios with Most in February 1967 to record the band’s next single, Little Games, a lightweight pop tune with vaguely psychedelic overtones. In keeping with Most’s production style, the tune was penned by an outside writing team, probably selected by the producer himself. Most also replaced Dreja and McCarty with John Paul Jones (once again) on bass and Dougie Wright on drums.

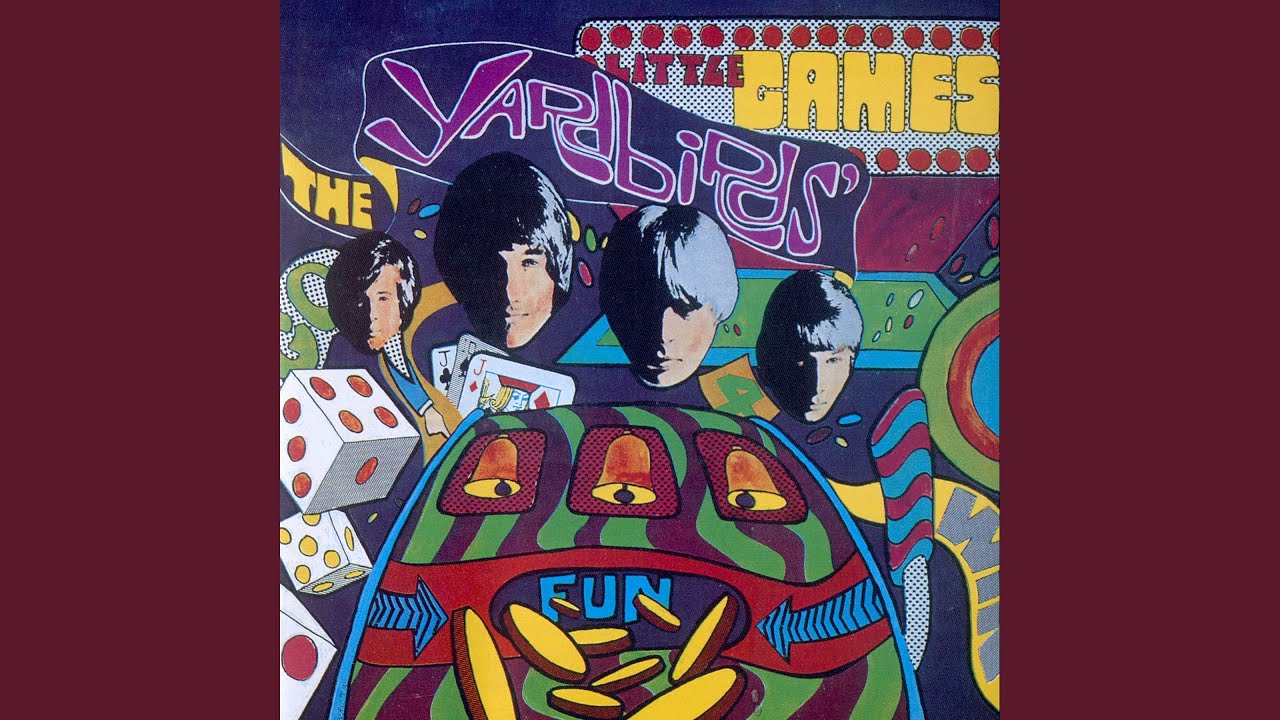

Little Games became the lead track and title of the album the Yardbirds made shortly thereafter. The album’s sessions were hurried – some accounts say the disc was made in as little as three days – and Little Games is a mixed bag, to say the least. Probably the most successful tracks are the album’s two blues-based numbers. Smile on Me, the first of them, was written by Page, Relf, McCarty, and Dreja, and boasts some of the most scorching blues licks Page has ever committed to record.

The album’s other outstanding blues track, Drinking Muddy Water, is basically the Muddy Waters song Rollin’ and Tumblin’ outfitted with a different lyric and attributed to the four Yardbirds as songwriters. Appropriation of older blues songs would serve Page again later on, most notably on Led Zeppelin II’s Whole Lotta Love, which drew from Willie Dixon’s You Need Love.

But several other songs on Little Games serve as noteworthy precursors to the direction Led Zeppelin would take. The instrumental track Glimpses has a moody, atmospheric vibe that makes it a significant antecedent to Led Zeppelin’s Dazed and Confused.

It’s one of two tracks on the album (the other is Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor) where Page uses a violin bow to play his guitar, enhancing the sound through a wah-wah pedal in this instance. It is, of course, a technique he’d employ more extensively in Led Zeppelin.

Another standout track, and an important Led Zep forerunner, on Little Games is the acoustic guitar instrumental White Summer. This is the song that would basically be reworked as Black Mountain Side on the first Led Zeppelin album.

Like Glimpses, White Summer reflects Page’s interest in Indian classical music, but what’s also remarkable about the track is how it combines those Indian influences with the strains of Anglo-Celtic folk music.

Page’s acoustic guitar on the track is in the popular folk tuning DADGAD. In his choice of this tuning he was influenced by two leading British folk guitarists, Davey Graham and Bert Jansch. Indeed, the main melody in White Summer was devised from the English folk tune She Moved Through the Fair, which had been recorded by Graham in 1963.

While Mickie Most strove to recast the Yardbirds as a light psychedelic pop act in the studio, Page took a completely different tack on the road, continuing to push the band in a more hard-hitting direction. Several of the many milestone rock albums released in 1967 confirmed that Page’s way was more in tune with what was to come.

Cream’s debut album Fresh Cream appeared early that year, followed by Disraeli Gears by year’s end. Jimi Hendrix’s debut disc, Are You Experienced, came out in May 1967. These three albums cemented the arrival of the instrumental power trio and a new riff-driven mode of rock expression. Also in 1967, a new group out of Los Angeles named Iron Butterfly released a debut album that would give a name to this new style of rock music. It was called Heavy.

Indeed, heavy was the direction in which Jimmy Page pushed the Yardbirds as they toured across America and the world in ’67 and early ’68, lapping up the miles as their Little Games album quickly slid down off the bottom of the charts and into oblivion.

Page seemed bound and determined to make the Yardbirds work, against all odds. This was the band that he’d abandoned his session career to join, and he stuck by them loyally. The group lived through three more dismal single releases following the commercial failure of Little Games. Although these discs are attributed to the Yardbirds, they were played entirely by Most’s session guys and bear no resemblance whatsoever to the Yardbirds’ style and sound.

Weighed down by such abysmal recordings, the Page/Relf/McCarty/Dreja Yardbirds finally called it quits, playing their last gig at the College of Technology in the small British town of Luton on July 7, 1968. McCarty and Reif went off to start a new band, Together, leaving the managerial custody of Peter Grant. This also left them free of Mickie Most. McCarty and Reif’s new group went to work on a debut album at Abbey Road, reuniting with Paul Samwell-Smith as their producer.

Page and Dreja stuck together initially, with the plan of drafting some new players and keeping the Yardbirds going. Page also formed a close alliance with Peter Grant at this time.

During a famous conversation in Grant’s car, while stuck in a London traffic jam, Page told the manager that he had some ideas for a new band and that he would like to produce the music himself this time. Grant jumped on the idea. It’s probable that he was eager to get rid of Most at this juncture, and if Page really could handle the production end of things, Most would then become less necessary.

A deal was struck: Most would work with Beck on his solo recordings, while Page would produce the new band he would assemble, which at this point was slated to be named the New Yardbirds. Grant would manage both acts. Beck fared better with Most than the Yardbirds ever had. With Rod Stewart on vocals, Beck released his admirable solo debut, Truth, in 1968, a classic album generally acknowledged as another key heavy metal precursor.

Meanwhile, Page and Dreja set off in search of a new drummer and lead singer. For the latter, Page had in mind a wailing, R&B belter like Steve Marriott of the Small Faces – and later Humble Pie – or Paul Rodgers, who was just getting started with Free at the time.

Page set his sights on an up-and-coming singer named Terry Reid, but Reid had just signed up to make a solo album (produced by none other than Mickie Most). However, Reid was able to recommend another singer to Page, a total unknown at the time by the name of Robert Plant.

Plant came from the English Midlands region near the industrial city of Birmingham, far from London both geographically and culturally. Though he had a solid grounding in R&B and blues, Plant was also deeply obsessed with the San Francisco psychedelic bands of the day, particularly Moby Grape and the Jefferson Airplane.

The young singer had been in a local group called Band of Joy that hadn’t gone very far. At the time when Page first contacted Plant, he was performing with another Midlands group called Hobbstweedle, a name very redolent of the elfin/Druid strain of British hippiedom born of a counterculture fascination at that time with J.R.R. Tolkien’s literary fantasy trilogy Lord of the Rings.

Plant was quick to recommend his friend John Bonham as a potential drummer for the group. Another Midlands man, Bonham had also passed through the Band of Joy’s ranks and had also had some success as a road drummer for Joe Cocker, Chris Farlowe, and Tim Rose. His relentlessly solid drumming would become the granite foundation of the band soon to become Led Zeppelin.

Right around this time, Chris Dreja dropped out of the picture. According to some accounts, he was less than thrilled with Plant’s voice, but he’d also decided to pursue a career in photography and quickly began to meet with success in that endeavor. (He would take the back cover photo for the first Led Zeppelin album.)

The bass slot left vacant by Dreja didn’t remain open for long. Page had already been contacted by his old session pal John Paul Jones, who was very interested in joining the new group he’d heard Page was forming.

Jones would prove to be a great asset to Page’s new band. Not only a superb bass player but also a classically trained organist, Jones was Page’s equal when it came to studio experience. He’d played bass and keyboards on countless sessions and done quite a bit of arranging – everything from Donovan’s hit Sunshine Superman to orchestral charts for crooners like Tom Jones and Englebert Humperdinck. All of Jones’ considerable skills would be put to use in Led Zeppelin.

The bassist was quickly admitted to the ranks and, by August 1968, the quartet that would shake the very foundations of rock music was firmly in place.

Using his deep studio connections, Page got them all a session gig backing Texan singer P.J. Proby on an album project. (Plant played tambourine.) This gave Page’s new group an opportunity to gain some experience working in a studio together. Following this, the fledgling band were off on a Scandinavian tour, fulfilling a Yardbirds commitment that was still on the books.

Page, Plant, Bonham and Jones played their first live show together on September 7, 1968, in Copenhagen. For this tour they were billed as “The Yardbirds, Featuring Jimmy Page.” On the road in Scandinavia, Page worked to mold his new quartet, much as he’d molded the Yardbirds on tour.

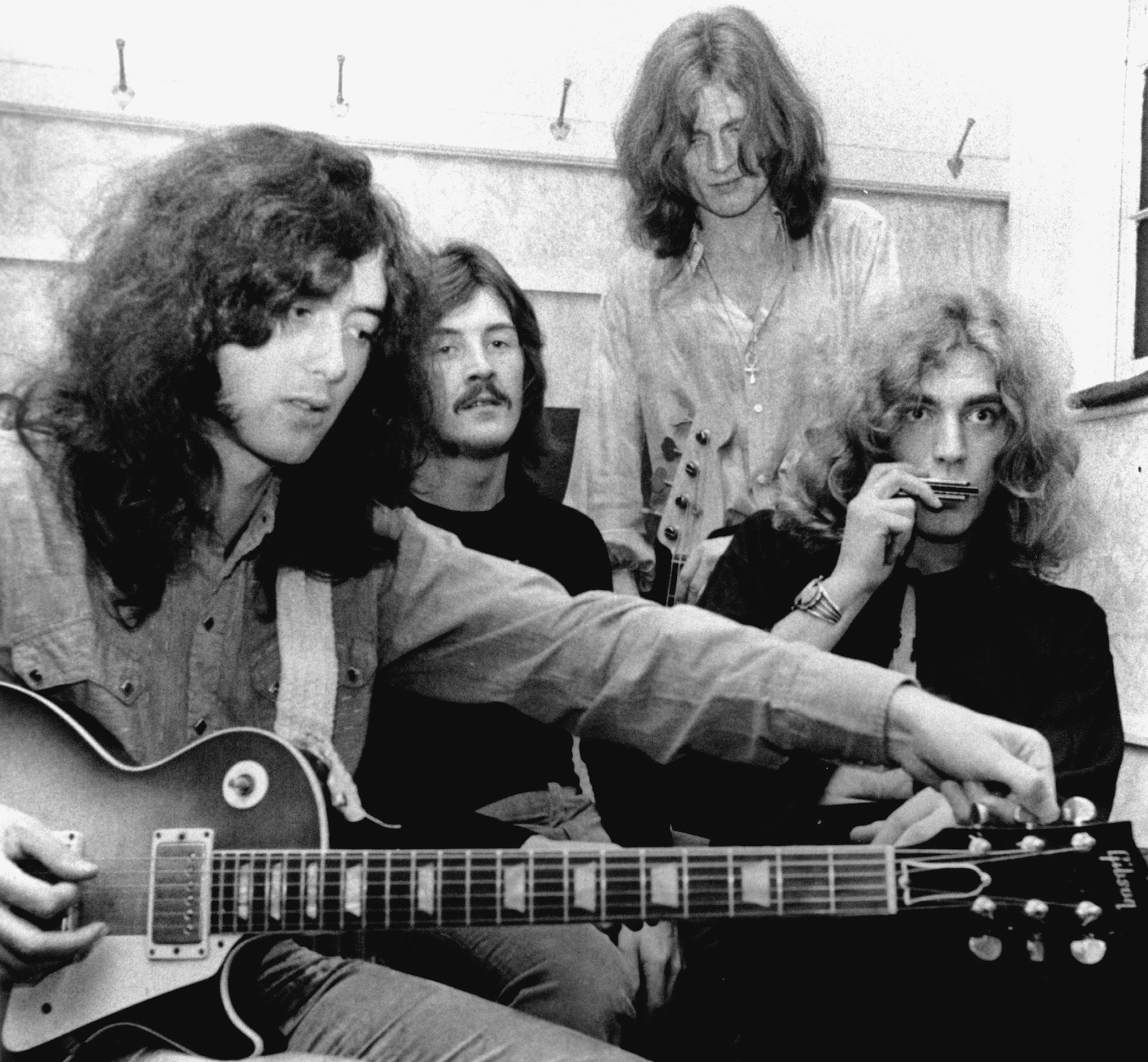

On September 28, 1968, Page, Plant, Jones and Bonham settled into Olympic Studios in London to begin work on their debut album.

For most of the first record, I used a Supro amp, a wah wah and a distortion unit called the Tonebender, which was one of Roger Mayer’s creations

The project was financed entirely by Page with funds he’d saved from his session work. He paid £1,782 (roughly $4,300 at the time) for 30 hours of studio time. Page knew he could nail the album in that tight time frame. He was fully in charge this time. There was no more Mickie Most to trip over.

“I wanted artistic control in a vise grip,” Page recalls, “because I knew exactly what I wanted to do with these fellows. It wasn’t all that difficult, because we were well rehearsed, having just finished a tour of Scandinavia and I knew exactly what I wanted to do in every respect. I knew where all the guitars were going to go and how it was going to sound – everything.”

The studio chemistry was conducive to success. The combination of two seasoned studio pros (Page and Jones) with two fresh newcomers (Plant and Bonham) made for an ideal blend of hard-won expertise and first-timers’ exuberance.

It also didn’t hurt that the engineer’s seat was occupied by Glyn Johns, one of the greatest rock engineer/producers of all time and whose work with the Stones, Who and other titans is the stuff of legend. By the time the sessions wound up in early October, the band had 12 tunes in the can. Nine of these made the final cut.

The album kicks off effectively with soon-to-be-classic Good Times Bad Times. The arrangement builds anticipation by starting off with a simple E power chord figure spaced at two-bar intervals. The drums mark time simply with an opening and closing hi-hat and then a cowbell, but when the main guitar riff finally enters, Bonham breaks loose with one of those lurching fills for which he would soon become famous.

Most people associate Led Zeppelin with big Marshall stacks and hefty Gibson Les Paul guitars, but Page recorded the first Led Zeppelin album mainly with a Fender Telecaster, with its thinner, single-coil pickup sound. In some instances, moreover, the Tele was direct-injected into the console and sent straight to tape from there.

“But for most of the record,” Page reveals, “I used a Supro amp, a wah wah and a distortion unit called the Tonebender, which was one of Roger Mayer’s creations.“

From his long studio experience, Page had learned the essential recording truth that small amps, like the Supro combo he used on the album, can produce very big sounds if you know how to mic them. And when he applied his miking know-how to John Bonham’s drum kit, the results were very thunderous.

“Essentially, it came down to moving the mic away from instruments in order to give the sound a chance to breathe,” Page explains.

“In my session days, I worked with this drummer called Bobby Graham, who was amazing. And you’d see him set up in this little recording booth with a mic shoved right next to his kit, and he’d be whacking the hell out of the drums, yet the recorded sound would be tiny. It didn’t take long to figure out the reason why.

“Drums are an acoustic instrument, and acoustics need to breathe. So when I recorded Zeppelin, particularly John Bonham, I simply moved the mics away to get some ambient sound. I wasn’t the first person to come across that concept, but I certainly made a big point of making it work for us.”

The vigorously up-tempo Good Times Bad Times is followed by a song that provides plenty of contrast, Babe I’m Gonna Leave You. Page had learned the song from a 1962 album, In Concert, by folksinger Joan Baez, whose work was quite popular in the Sixties, owning in part to her close connection with Bob Dylan.

Led Zeppelin’s performance doesn’t depart much from the chord structures Baez uses in her recording of the song, but it introduces a heightened sense of drama by means of sharply articulated dynamics, something that Page would frequently refer to as “light and shade” in interviews.

Next up is the Willie Dixon song You Shook Me, a classic slow, 12-bar blues performed by the band with admirable panache. With this track, Led Zeppelin’s original audience would have been on very familiar ground.

When we recorded You Shook Me, I told Glyn Johns that I wanted to use backward echo on the end. He said, ‘Jimmy, it can’t be done.’ I said, ‘Yes it can. I’ve already done it’

During the late Sixties, interest in the blues on the part of the white rock audience reached a high point. British Invaders like the Stones, Animals and Yardbirds had started the ball rolling, but Eric Clapton’s work with Cream had really focused attention on the blues and on Clapton’s work with his prior band, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

Page’s reverb-drenched guitar work on You Shook Me eloquently demonstrates that he was no stranger to the blues idiom. He tosses off masterful lead lines and also doubles Plant’s vocal on slide guitar, one of several instances on the album where it seems like Page is employing the singer’s voice as an extension of his guitar.

Page’s guitar solo is punctuated by dramatic pauses and drum fills. And the song’s ending introduces a ritual that would be repeated over and over again on arena rock stages in the decades to come: the “whee-whee, ahh-ahh” call-and-response riff trade between lead guitarist and lead singer.

The ending of You Shook Me is further enhanced by a backward tape echo effect on the guitar. It was something that Page had discovered during sessions for one of the final Yardbirds singles, Ten Little Indians. Desperate to do something cool with an embarrassingly uncool horn arrangement (albeit one by John Paul Jones), Page hit on an inventive idea.

“I said, ‘Look, turn the tape over and employ the echo for the brass on a spare track,’” he recounts. “ ‘Then turn it back over and we’ll get the echo preceding the signal.’ The result was very interesting. It made the track sound like it was going backward.

“Later when we recorded You Shook Me, I told Glyn Johns that I wanted to use backward echo on the end. He said, ‘Jimmy, it can’t be done.’ I said, ‘Yes it can. I’ve already done it.’

Then he began arguing, so I said, ‘Look, I’m the producer. I’m going to tell you what to do – just do it.’ So he grudgingly did everything I told him, and lo and behold, the effect worked perfectly. The funny thing is Glyn did the next Stones album and what was on it? Backward echo!”

The fourth song on the album, Dazed and Confused, ended the first side of the original vinyl album with a tour de force performance soon to become a cornerstone of the Led Zep canon.

The basic arrangement is much the same as one that Page had worked out previously with the Yardbirds, but the Led Zeppelin version benefits from the full gamut of Page’s production techniques, not to mention the performances of three other musicians more conducive to the style Page was going for.

John Paul Jones’ bass is heard first, stating the song’s druggy, descending main riff, while Page creates atmosphere via heavily echoed guitar harmonics. Bonham comes crashing in like a bull in a china shop and the song settles into its ponderous groove like a large boat righting itself after a cataclysmic wave. Page fattens the main riff appreciably with double-tracked octaves on guitar.

The song moves through a series of tempo changes, including an up-tempo part that is clearly descended from the Yardbirds legacy of rhythmic change ups. The extended instrumental section includes some passages in which Page plays his electric guitar with a violin bow.

Now at the production helm, he was able create a much more effective sonic ambience around the bowing effect on the first Led Zeppelin album than he had been on the Yardbirds’ Little Games album. Much of this ambience comes from an EMT plate reverb, an old-school, pre-digital studio reverb device.

“There was a lot of EMT plate reverb on that album,” Page explains, “put to tape and then machine-delayed.”

The instrumental interlude in Dazed and Confused is also punctuated by much erotic moaning on the part of Robert Plant, which is also quite reverb-drenched. This would soon become one of the singer’s vocal trademarks.

Commentators often explicate the open sexuality of Plant’s vocal performances as an expression of the late Sixties “free love” aesthetic. But Plant was taking his cue less from hippie heart throbs like Jim Morrison and more from rock and roll’s original blatant sex icon, Elvis Presley. The Fifties rock star is one of Plant’s prime influences.

“Elvis always had these great reverbs on his voice,” Plant says, “especially when he signed to RCA [Records] and did Love Me and Any Way You Want Me. I mean, the vocal sound and compression are absolutely brilliant. And I’ve always wanted to get lost in the reverb, too. The effects become sort of an accompaniment. But it’s an extension of me.”

Side two of the album’s initial vinyl release commences with Your Time Is Gonna Come. The song boasts a classical organ intro courtesy of John Paul Jones, who used to play the organ in his local church when he was just a lad, but the high-class organ intro soon resolves into a tidy little classic rock ballad.

It’s followed by the aforementioned Black Mountain Side, an open-tuned acoustic guitar number with tabla accompaniment. Here, Page is clearly reprising what had been a winning formula on White Summer, his solo guitar turn on Little Games, evoking both Indian ragas and Anglo-Celtic folk motifs. Page even weaves a few melodic quotations from White Summer into Black Mountain Side.

A deft tape edit takes us directly from Black Mountain Side into Communication Breakdown, another all time Led Zep classic. This concise, up-tempo rocker is built on an archetypal E, D, A chordal motif.

Page’s frenetic guitar solo is particularly bright and Tele-castic in timbre. It builds so much crazy momentum that it spills over into the chorus that follows, as if the guitarist couldn’t stop the runaway train he’d set rolling down the tracks.

I remember analyzing the records of the Fifties, especially the Sam Phillips stuff, and listening to the echoes

Jimmy Page

I Can’t Quit You Baby is side two’s great slow blues number, a companion piece to You Shook Me on side one. Both songs were written by the same author, the great blues tunesmith Willie Dixon.

The guitar soloing stands among Page’s finest work in the blues idiom. His tone is enhanced by slap-back echo, a tape-based delay effect frequently used on early rockabilly recordings of the Fifties, particularly those emanating form Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios. Sun’s early recordings by Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins and other rockabilly icons had a profound influence on Page when he was a youngster.

“I remember analyzing the records of the Fifties, especially the Sam Phillips stuff,” he says, “and listening to the echoes. I’d listen to [Elvis Presley and Ricky Nelson guitarist] James Burton, ’cause I was learning off those records and listening to where they’d slide up the reverb on certain notes. And that’s exactly the same sort of techniques I used later with Zeppelin.”

The album closes with another epic recording, How Many More Times. The main verse structure of the tune is based around a bluesy walking bass line, but the track soon wanders off in myriad directions.

The episodic journey includes breakdowns, drum fills and double-tracked guitar leads. At one point, the band goes into a bolero, creating the precedent for another enduring stock arena-rock move. And in two spots, John Paul Jones busts out classic Yardbirds/Paul Samwell-Smith “rave up” bass crescendos.

“That has [everything but] the kitchen sink on it, doesn’t it?” Page acknowledges. “It was made up of little pieces I developed when I was with the Yardbirds, as were other numbers, such as Dazed and Confused.”

It has often been observed that the first Led Zeppelin album is very much a document of the band’s live set at the time. It’s a testament to their musicianship that they were able to assemble such a tight set of material in the short time they’d been together before making the album. But the time frame also helps explain the relative scarcity of original material.

Of the album’s nine songs, three are covers, one is a liberal adaptation of someone else’s song, and one is a collage of familiar blues motifs.

Out of all the tracks that went down to tape during those 30 hours, Page selected the best, favoring original material as much as possible and building a cohesive, well-paced album. The two sides of the original vinyl LP mirror one another in many ways. Each side contains a slow blues, an acoustic-driven folk-based number and an episodic epic fashioned from blues-based themes.

Peter Grant had little problem getting the project signed to Atlantic Records in the United States, but even as the contract was being signed, the plan was still to call the band the New Yardbirds. This was changed on the eve of the band’s first gig following the album sessions when they received a cease-and-desist order from Chris Dreja’s attorney.

And so a hasty search began for a new name. Page recalled a joke Keith Moon had made in 1967. At the time there was some consideration given to forming a supergroup consisting of Page, Beck, Moon and his fellow Who member, bassist John Entwistle.

Moon had quipped, “That’ll go down like a lead zeppelin!” – a turn of phrase based on the show-biz saying “That’ll go down like a lead balloon.” Page simply changed “lead” to “led,” thus avoiding any confusion over pronunciation, and his new band had a name that would prove to be among the most enduring in rock’s history.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.