Vito Bratta reflects on the ‘80s, when White Lion were kings of the hard-rock jungle, and the guitar rulebook was being rewritten by Eddie Van Halen

Best of 2022: It’s late 2019 and Vito Bratta has started playing electric guitar again. Just around the house. 10 minutes here, 30 there. He’s careful not to play too long at one time, to avoid reinjuring his right wrist, which has been delicate since he heard it snap one day in 1997.

It was a freak accident that happened as he was playing guitar lying on his back, wrist at a weird angle, while watching a baseball game on TV.

These days when Bratta picks up an electric guitar and plays, it’s often classical-influenced arpeggios played with a pick. “And then every once in a while,” Bratta tells Guitar World, “I start relearning stuff from back in the day.” Meaning the brilliant, melodic guitar parts he played with his multi-platinum hard-rock band White Lion from the mid Eighties through the early Nineties – before Bratta walked away from the music business entirely.

Few guitarists during his heyday or since have wielded the balance of flair, feel and fearlessness – the soaring solo and singing fills on White Lion’s signature hit song Wait, for example – that made Bratta’s playing so distinctive and thrilling. Summoning that style can even be elusive for Bratta.

“I can’t figure out some of my own stuff,” Bratta says early on during our two, 90-minute phone interviews. “For the longest time I said I’m not gonna learn that Wait solo because I don’t remember what I did. But it came back to me.”

Bratta lives in the same Staten Island [NYC] home where he grew up, and the red Lamborghini parked in the driveway is a rare extravagance. Besides supercars, he’s been careful with his money, invested wisely and derives a solid income from his White Lion songwriting publishing and royalties. “The thing about the band was, we were worldwide,” Bratta says. “I’ve gotten checks from Zimbabwe, from Lebanon and every single country you can imagine.”

In the summer of 2018, Bratta went up into his attic, and for the first time since recording White Lion’s 1987 breakthrough sophomore album, Pride, brought down the case containing the remnants of the guitar he used to record that album: a sunburst 1979 Fender Strat modified Van Halen-style with one humbucker (Seymour Duncan JB), one volume knob and a Floyd Rose tremolo system.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The strings he used to record Pride were still on there. Alas, the guitar had seen better days. Foam inside the case had liquified from being up in a hot attic for decades. The Strat was his talisman since White Lion was coming up in rock clubs, including legendary Brooklyn hotspot L’Amour. “It’s ridiculous how I wore it out,” Bratta says of the Strat. “It was almost fretless. But I couldn’t afford a fret job, so I did the album with that guitar.”

On Pride, Bratta played the Strat through a Tube Screamer overdrive pedal and into an old 100-watt Marshall Super Lead, which he still has somewhere. After he finished his last guitar track for the album, he put the Strat back into its case.

“And I hear it pop,” Bratta recalls. “The wood shattered inside where the Floyd Rose connected. So the guitar recorded Pride – and then it died in front of me. It just snapped. It was terrible.”

He removed the humbucker, which he later installed in some of his other guitars.

Bratta still has all his main White Lion-era guitars, some of which he recently put hands on for the first time in decades. “I went out in the garage,” Bratta says. “And all of a sudden after all these years I got the bug back, so I started taking out all these guitars.”

The ESPs he often played onstage. The Steinberger GM2S with the White Lion decal. Back up in the attic, Bratta found his “childhood guitars,” including a ’75 Les Paul Custom and mid-Seventies Ibanez Destroyer.

When all those PA cabinets are on the stage in a 20,000-seat arena and you do a dive-bomb, the feeling is like the floor just gives out

Since excavating them, he’s mostly left all those vintage electrics alone. Instead, Bratta purchased his first new guitars in maybe 40 years, a Gibson Les Paul Special and a Gretsch Duo Jet. He specifically wanted guitars that didn’t have a tremolo bar.

“What a crutch that was, you know?” Bratta says. “I found my playing went downhill live. Whereas in the old days, you’d end the song and just play some solo at the end or whatever, then it became you just reached for the bar and start a dive-bomb. But it was a load of fun. Because when all those PA cabinets are on the stage in a 20,000-seat arena and you do a dive-bomb, the feeling is like the floor just gives out.”

Classically infused Ozzy Osbourne guitarist Randy Rhoads had been Bratta’s last major influence. “My electric guitar playing always went hand-in-hand with classical,” Bratta says. After White Lion’s tour supporting fourth LP Mane Attraction limped to a conclusion in 1991 with the band back in clubs, Bratta had a plan for his next move.

“My hope was that after White Lion after a few years I was going to put out a classical album,” Bratta says. “And the difference was I was going to write all the songs, and I wasn’t going to do the standard classical repertoire.”

That never came to pass, though, because Bratta’s fingernails, critical in classical technique, have become brittle as he’s gotten older and tend to break off easily. This has prevented what would’ve likely been, given his melodic and compositional gifts, an intriguing musical phase for him.

Still, after his wrist injury, the nylon strings were easier for him to manage. Throughout his years of seclusion, Bratta has kept a classical guitar nearby.

There are several reasons Bratta left the music business, the music business being chief among them. Bratta and the band worked hard on 1991’s Mane Attraction. It’s his favorite White Lion album, informed by the band’s recent tour with Ozzy Osbourne and looking to write heavier material. But like many Eighties bands who released strong albums in the early Nineties, Mane Attraction didn’t get a fair shake.

“I knew what decades mean to people,” Bratta says. “I know that the Sixties ended and the Seventies came in, then the whole Eighties thing came in. So I knew that was coming down the pipe.”

One of the record company guys says, ‘You know what your problem is? You play too good. You need to start playing sloppy because that’s what the kids are into nowadays

He witnessed this firsthand one day while at Atlantic Records’ New York headquarters, overhearing Robert Plant’s manager yelling at label reps for pushing new bands like White Lion and Ratt instead of Plant, the former singer of hard rock’s biggest band ever, Led Zeppelin. But that doesn’t mean it goes down nicely.

Bratta recalls, “One of the record company guys says, ‘You know what your problem is? You play too good. You need to start playing sloppy because that’s what the kids are into nowadays,’ and I took that as my exit. You gotta be kidding. You want me to suck?”

Bratta was not born to suck on guitar. As a child, he was first drawn to the instrument from watching musicians like Hee Haw country virtuoso Roy Clark play on TV. Listening to AM radio, he was entranced by Elton John’s early piano-pop hits, an early root of Bratta’s later song-within-a-song guitar solos for White Lion.

He also loved Mountain’s greasy rocker Mississippi Queen, and decades later he ended up with one of Leslie West’s Marshalls. He started playing guitar around age 13. Cream, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath seeped into young Bratta’s musical mix. He put together a garage band doing songs like Free’s anthem All Right Now.

“There’s an eight track cassette [recording] somewhere,” Bratta says, “of me playing that when I was 15 or something at a rehearsal.”

In 1977, he went to see Jimmy Page, one of his guitar heroes, perform with Led Zeppelin at Madison Square Garden. His seats were so far back he scribbled his name on the storied arena’s ceiling. Eleven years later, Bratta would be onstage at the Garden with White Lion, opening for AC/DC.

During his formative years, Bratta was in a cover band called Dreamer that worked the New Jersey club scene heavily, crossing paths with future stars like Nuno Bettencourt and Dee Snider. He’d often play guitar 15 or more hours a day, arriving at gigs hours in advance to practice backstage.

Eventually, Bratta teamed with Mike Tramp, a talented Danish singer who’d moved to New York, to form White Lion’s creative nucleus. According to the guitarist, the “White” in the band’s name was added after a copyright conflict.

“On the way home from Manhattan, we drove past a White Castle [fast-food restaurant],” Bratta says. “I said, ‘What about White Lion?’”

White Lion recorded their 1985 debut album, Fight to Survive, in Germany, a country that would remain a strong market throughout the band’s history. A clear Rhoads-era Ozzy influence can be heard on the title track. Lead single Broken Heart mixed dramatic dynamics, Tramp’s sexy bay, a driving groove and Bratta’s sidewinding soloing.

Eddie Trunk was a rising New Jersey-based disc jockey who frequented L’Amour, which was run then by the same people managing White Lion. Management got a Japanese import copy of Fight to Survive into Trunk’s hands.

“At that point in America, nobody even knew who they were,” says Trunk, who went on to become one of rock’s most influential tastemakers on radio and TV. Listening to White Lion’s debut for the first time, Trunk was “just blown away, because it checked all the boxes for what I loved in hard-rock music. I became a fan pretty instantly.”

Bratta and White Lion took a big step forward on Pride. With heavy-music genius Michael Wagener as their new producer and with a potent new rhythm section (bassist James LoMenzo and drummer Greg D’Angelo), recording took place at North Hollywood’s Amigo Studios. Bratta has fond memories of the sessions, including hanging with Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones.

Most importantly, the Pride sessions changed the guitarist’s recorded sound forever and energized White Lion’s music.

“It was Michael Wagener that pushed me,” Bratta says, “to just play the way I was always playing live, and not to be so clinical and stiff, play rhythm guitars first and then go in and play fills, which are never going to feel right.”

On Pride, Bratta now weaved hooky fills and arpeggios into his rhythm playing. This became a signature part of his guitar style, and lifted Wait into acid-washed power-pop ecstasy and a top 10 hit.

Around this time, Bratta had begun a new way of composing solos that enhanced his playing’s melodicism. To avoid falling into finger-memory scale-cliches, he’d listen to a song and compose the solo singing in his head and later learn it on guitar.

Most of the solos are vocal melodies that later got embellished with guitar technique. Out of 20 notes of a melody in a solo, five of them might be the melody

“Most of the solos are vocal melodies that later got embellished with guitar technique,” Bratta says. “So out of 20 notes of a melody in a solo, five of them might be the melody. The others are little embellishments, little tricks or whatever.”

This composition method helped Bratta become one of few guitarists to do post-Van Halen two-hand finger-tapping in a cool, non-caricature way. He’d turn to tapping when his head-composed solos ranged wider than his left-hand’s finger stretching ability.

“So how do you fix that? You’ve got to use your right hand, the Van Halen technique,” Bratta says. He’d also drop in some tapping for tonal color. “It eventually just becomes part of you.”

After Pride broke, some accused Bratta of being a Van Halen clone. It was a lazy knock, partially biased by the fact Bratta’s long, dark-haired look evoked early Eddie. That’s not to say – like most guitarists of his generation – Bratta wasn’t inspired by EVH. “After the first Van Halen record, he changed the way people play,” Bratta says. “He rewrote the book. I’m 16. Guess who was buying the book?”

Still, producer Michael Wagener says, “Vito always had his own style. That was the time of all those guitar players who had not the same but similar ideas, and Vito tried to stay away from that.”

Along with George Lynch and Zakk Wylde, Wagener says, “Vito is in the top three guitar players I’ve ever worked with.”

Bratta eventually became a friend of Van Halen, who gave him one of his signature guitars. They also played basketball and sped around in sportscars together when VH and White Lion were rehearsing at the same facility. Bratta’s other primary touchstones include Stevie Ray Vaughan. After SRV’s passing, he recorded the soulful White Lion instrumental Blue Monday in tribute to the Eighties blues great.

Trunk was the first person to ever play White Lion’s music on U.S. radio. The band never forgot this. After White Lion received their first gold record for Pride, they gave it to Trunk.

In 2007, Trunk coaxed the reclusive Bratta into the studio for the guitarist’s first interview in about 15 years. In the interview, Bratta shed light on why he stepped away, including his wrist injury and the years he’d spent as caregiver for his ailing father.

Put my mom in a home just so I could go on tour? I’m not gonna do that

When I talk with Bratta in 2019 after Trunk graciously connected us, the guitarist remains dedicated to his family. His father has passed and he’s now caring for his mother at home, as well as looking after another family member.

“And, of course, everybody out there is like, ‘Come on, you could do tours,’” Bratta says. “Put my mom in a home just so I could go on tour? I’m not gonna do that.”

Since the 2007 radio interview, Bratta sightings have been rare. He turned up later that year at two New York shows celebrating the now-defunct L’Amour. In 2015, he popped up at a Cheap Trick’s Staten Island gig to see his old friend Rick Nielsen.

Both times, Bratta sang backing vocals onstage but didn’t play guitar. Bratta was interviewed for Nothin’ But a Good Time, the excellent Eighties rock/metal oral history by Richard Bienstock and Tom Beaujour, published in 2021.

But in general, Bratta’s fade from public life has been so extreme it makes notoriously private former Guns N’ Roses guitarist Izzy Stradlin seem publicity-thirsty.

I do miss it, and I regret that I was given a certain amount of talent to do something, and I don’t use it

For White Lion’s third album, 1989’s Big Game, Bratta adopted cleaner chiming textures, as heard on Little Fighter, a spirited Greenpeace-themed single (Tramp was refreshingly willing to go beyond babes and booze for lyrical inspiration) with a canyon-soar guitar solo.

Like Wait and many other Bratta solos, Little Fighter was a first take. The solo Bratta is proudest of from his entire career is also off Big Game, the restrained yet expressive lines on Baby Be Mine. He says, “It sounds like it’s an echo machine, but it wasn’t. It was just me playing along with myself, and I just love the way that came out.”

Occasionally he’ll happen across a White Lion tune on the radio. He can’t recall how he arrived at some of his bolder phrasing choices, shrugging it off with a sports analogy of “being in the zone.” Bratta tries to avoid watching White Lion music videos or live footage online. “It’s difficult, you know, because I do miss it,” Bratta says. “And I regret that I was given a certain amount of talent to do something, and I don’t use it.”

So is there any chance Bratta would return to the stage, even just for one show? “I couldn’t ever, ever say no to that,’ he says, “because it hurts not doing it. But a lot of things would have to change around here for me to be able to walk out of the house.”

Still, he adds, “I’m just happy that I left it all out on the field. Sometimes I really feel like I exceeded my ability.”

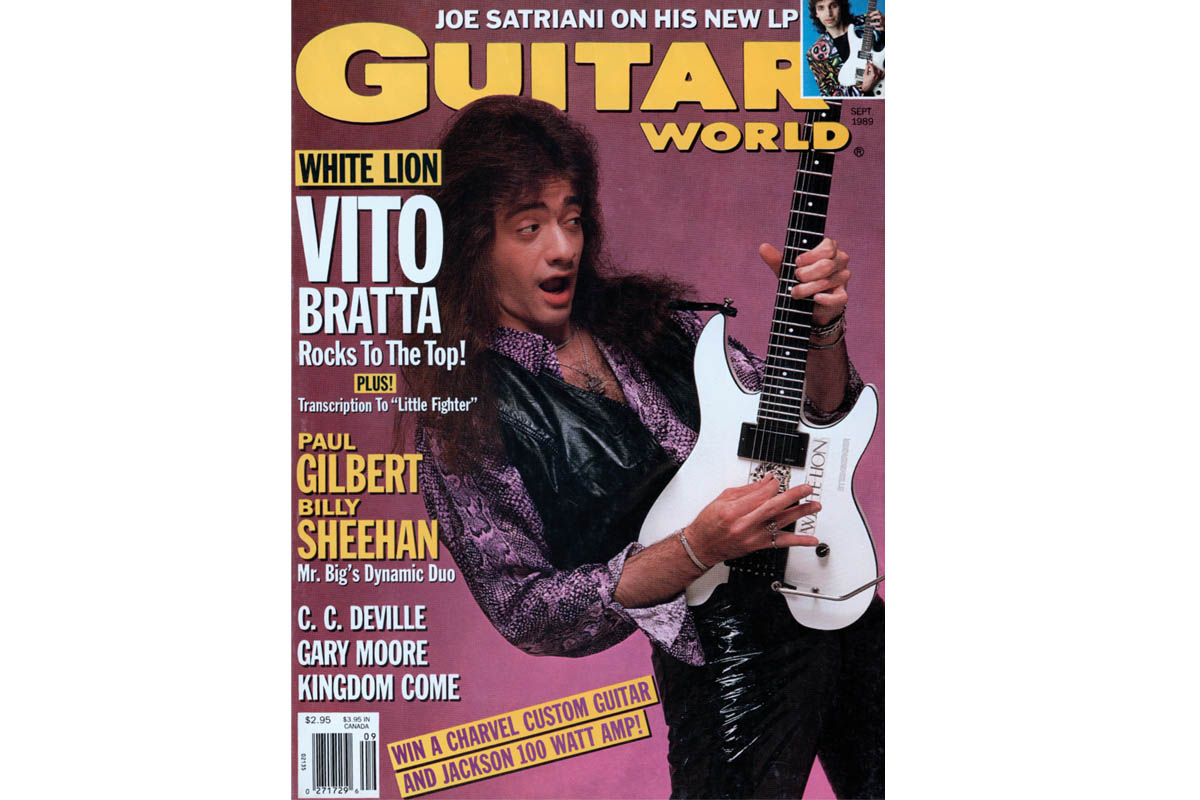

Bratta graced the cover of Guitar World’s September 1989 issue, brandishing his Steinberg and clad in a purple snakeskin shirt and black leather vest. The cover is framed and still up on a wall at his home. During our conversations, he thanks me for every single compliment. As we’re getting off the phone, Bratta says, “Thank you for just even remembering me.”

During White Lion’s prime, Bratta was constantly amazed by the crowded heat of MTV-era guitar-thoroughbreds. During our conversation he lauds players including Nuno, Slash, Joe Satriani and Reb Beach. Skid Row guitarist Dave “Snake” Sabo is one of the few of his colleagues he’s maintained contact with, though.

In recent years, he’s reconnected with White Lion drummer Greg D’Angelo. As of the time of this interview, he hadn’t spoken to bassist James LoMenzo since the band broke up. As for frontman Mike Tramp, “We’ve been in court against each other,” Bratta says, referring to legal action regarding usage of the band name White Lion. “We’ve had arguments, but it’s not like we hate each other. We just don’t talk.”

Many rock fans and guitarists still talk about Vito Bratta, though. He’s humble and perhaps a little naïve, though, at just how badly he’s missed and how much people would love to hear from him again. If a White Lion reunion isn’t on the cards, perhaps an instrumental solo album. He’s amazed people still care about music he made 35 years ago. “And to hear that people do,” Bratta says, “how could I want any more than that?”