"Unfortunately I can imagine that because nothing would surprise me": The Living End's Chris Cheney on AI punk bands, going back to basics, the Spotify exodus and rock 'n' roll as a life force

The teenagers who loved 'Prisoner of Society' in the '90s are now in their forties, but on new LP I Only Trust Rock n Roll, The Living End sounds as vital as ever.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For a while it felt like there might not be another Living End record. The punkish Melbourne three-piece – comprising Andy Strachan on drums, Scott Owen on double bass and Chris Cheney on guitar and vocals – released their last LP, Wunderbar, in 2018. Seven years is a long time for the Living End: the three-piece has released eight LPs and six EPs since forming in Melbourne's beery punk and rockabilly underground in 1994. And into the picture is Cheney's 2022 solo record The Storm Before The Clam, which could have signalled a shift in creative priorities.

Their new LP I Only Trust Rock n Roll allays these fears. Not only does it sound like The Living End never went away (though they've still played live during their recording intermission), it almost sounds like The Living End never crossed through to the 21st century. This is the most impactful, hook-laden record the group has released for decades. The rockabilly, psychobilly and punk influences are still abundantly present, but the songwriting focus has shifted towards something akin to power pop: no substandard chorus or hook is granted entry here. For anyone who has forgotten what made this group distinctive, it's here in all its melodious, harmonious – almost bubblegum-like – glory.

The Living End did intend to strip things back with their ninth record, but that had more to do with the songwriting process than how I Only Trust Rock n Roll actually sounds. Australian Guitar caught up with Chris Cheney in the weeks before the new record's launch to talk about the songwriting process, punk-rock assertiveness, and how a 30-year-old rock group is weathering seismic changes in the record industry.

The Living End has been around for over 30 years. Punk and rock bands so often live and die within a couple of years: Did you have any sense that the group would have this much longevity?

Oh, no. You can't. I don't think you can, especially not the scene that we came from. It was such a unique kind of little subculture with the bands that we were playing with, you know, the rockabilly, psychobilly, ska, punk thing was kind of small in Australia, so you kind of knew everyone. There were a few hundred people in the scene and you played in that scene and the idea of breaking out of that, or having a long career, was not something that you ever imagined. I suppose secretly we would have dreamed that way: wouldn't it be great to be able to be a musician forever?

I'll tell you what, though. We were really ambitious even from early on. I was ambitious in the way that I thought this music should be exposed to more people. Why aren't there more people going to the Royal Derby on a Sunday afternoon to watch the rockabilly and swing bands and stuff that we used to go and see? It was great music, a great scene, it had everything going for it, but it was still small. But I felt like when we started to write our own songs and we actually started to get OK at it… 'From Here On In' and those sorts of songs – those early ones – I thought there's no reason why this music can't be mainstream and can't cross over. There's no reason why we couldn't make a living out of this for a few years.

Obviously that was before the first record came along and that just exploded in a way that I don't think anybody could have imagined. I remember all of our friends in that particular scene were like: you guys were always getting more popular than everyone else, but no one could have imagined that it would be this number one record in the charts for 15 weeks or whatever it was. For Scott [Owen] and I, it was beyond anything we could have imagined.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That was a long answer but at the heart of it is rock 'n' roll, and people need rock 'n' roll, so it makes sense to me that we are still around. We've always worked our arses off and tried to be a great live band. It matters.

I've listened to the record about half a dozen times at this point. It feels like a power pop record. There's no fluff, there's no halfway-there chorus, it's very impactful and melodically rich. You've said you wanted to make a stripped back, lean and punchy record. Why? And has the Living End ever made anything that overblown, or at odds with this record?

I think we have made stuff in the past that's been overblown. Even White Noise, which was a huge album for us – we recorded that in New Jersey. There's strings, pianos, all this extra stuff on there, and it's fine because I think it's kept in check. But we have on occasion gone too far with adding overdubs. It's a long way from our three-piece rockabilly roots I suppose. We always said we wanted to grow as a band and grow as songwriters and explore different things, and our record collections were always really diverse: it was never just rockabilly or psychobilly.

I think of the Living End as a rock band. We've threatened over the past 10 years, "Oh we're gonna make a stripped-back record, and it's going to be really quite simple," but then it hasn't worked out that way. And even this one, I guess it's not stripped back, I feel like the writing is stripped back. The production still has what it needs but it's not bloated. It's a good balance. I'm still doubling up choruses on the guitar, there are still lead breaks and rhythm underneath. Why did we do that? I don't really know. It's just wanting it to sound as big as it can, and I think probably some of the songs just sound better. We would put the rhythm guitar in and go "OK, let's do a take of that. Is it better now, or was it better before?" And I think we always agree that with this album, just having a few of those embellishments [is fine], as long as you keep it in check.

We've always had that political kind of thing, but I've never wanted to sort of portray us as a political band, because I think the Oils – they've done it the best.

But the difference with this record is the songs are just really lean and stripped back. I've never pressed delete more often than I did when I was writing this record. I would demo an idea here in my garage, listen back, and I'd be really brutal with cutting it up. I'd say, "Right, that little bit leading into the guitar solo is a good part, but does it need it? No! Get rid of it." Keep everything lean like a hot rod and it's only going to be better once the three of us tackle it, because there's just no fat. It's about whether it could work as a song… if the choruses are catchy and it has the right kind of hooks. It's not just about the energy: you have to have good songs.

'Camera' is a brilliant rock tune. That four-chord riff is simple on paper but, of course, when the group comes together it's bigger than the sum of its parts. How does something like that riff show its promise during the songwriting process? It might sound prosaic when you're playing it alone in your garage, right?

I think you said before, power pop record? I feel like I'm influenced by great power pop songs, whether that's more melodic Nirvana stuff, or Tom Petty, or Superchunk. I'm such a fan of melodies: Neil Finn kills me. I can't write an angry linear powerful rock record; there's always these flowery choruses and harmonies that always have to be in there for it to get any further than my garage. For it to get any further it has to have this extra thing. I'm happy with that, I don't want the emphasis to just be on the energy where you're like, “Yeah, it's cooking, but where's the fucking songs?”

I do a lot of drafts of songs. With that one ('Camera') I had a verse that I thought was catchy, and then I thought, well, it needs a chorus that kinda matches that… it's difficult to explain songwriting. I guess everyone does this, but I just sort of search and hum and make noises and hit different chords just trying to push myself to the point of making an accident: "Oh there it is, that's what it needs!". [Songwriting] is life's great mystery.

This lyric on 'Strange Place' stood out to me: "I can't imagine what will happen in the next 20 years / I'm jumping off the wagon and back on the beers". It's a relatable sentiment. As you say, there's all this gorgeous melodicism and this energy and power on this record, but there's also a sense of exhaustion with the modern world and recent history. Can you speak to that a little bit?

I suppose the songs that people associate with The Living End the most are the ones where we are kind of on a soapbox: 'All Torn Down', 'Prisoner Of Society', 'West End Riot'. We haven't really been opinionated all that much on our last few records, whereas people are responding to that on this [new one]. They go: it sounds pissed off again. And I think I kind of have been. As you said, the frustrations… I guess I've found myself more in the last five years just shaking my head – whether it's the TV or devices or whatever it is – just shaking my head and feeling like I don't understand where everything's headed. I can't comprehend it. I don't like where some things are headed. When you have your own children, you start to worry about the future.

I did go through a period there when I had maybe seven or eight months without a drink, which for me was the first time I'd ever done that since I was 18. I'd never had a break like that before. And then through writing this album, I got to a point [as described in] 'Strange Place', for example, which was a way of saying "fuck it – I need a drink! This is all too hard, the world is doing my head in.” I definitely felt like I had something to say on this record. I wasn't pushing myself [to do it], there just happens to be great inspiration wherever you look.

As you say, The Living End has had these political elements right from the beginning. It's always been part of your DNA. But it feels like, during this decade in particular, people are more polarized than ever. Sentiments that might have seemed fairly innocuous 10 years ago are suddenly risky to express. For instance a song like 'Public Holiday' [which advocates changing the date of Australia Day] – that will be polarizing. I'm wondering whether you feel that there's a risk in writing a song like that.

I'm well aware of what the backlash will probably be now that everyone's got a voice and a platform to be able to express that opinion. But that's fine too, you know, that's free speech. It's just how I feel, it doesn't have to be how everyone feels, but a song like that: I find it sad and disappointing, as well as disrespectful that we can't be grown-ups and have an adult conversation about, well, "perhaps it might suit everyone to think about changing the date and maybe we can have a date where everyone celebrates the greatest country in the world". People get really angry about it; they shut it down: "no you can't change the date, it's Australia Day". It's just a lack of being able to talk about it. People are sick of the talk as well. It's time for action; just change the damn date.

A lot of these songs were written with the emphasis on the right hand, just strumming fast, punk rock downstrokes, and hitting barre chords.

We've always had that political kind of thing, but I've never wanted to sort of portray us as a political band, because I think the Oils – they've done it the best. They're qualified, and they've read enough that they know what they're talking about. I do get passionate about things and I'm all for equality and fairness and I don't like seeing people being hard done by. I'll leave the soapboxes to the Peter Garretts and Joe Strummers of this world. I'm glad that the band has had songs that do have something to say, and people have been affected in a positive way. I get a lot of younger people coming up to talk about 'All Torn Down' or something. It's just still so relevant and those songs made me think, you know, more than just listening to an Iron Maiden record or something. At the same time it's great when someone just wants to talk about a guitar solo or something [laughs].

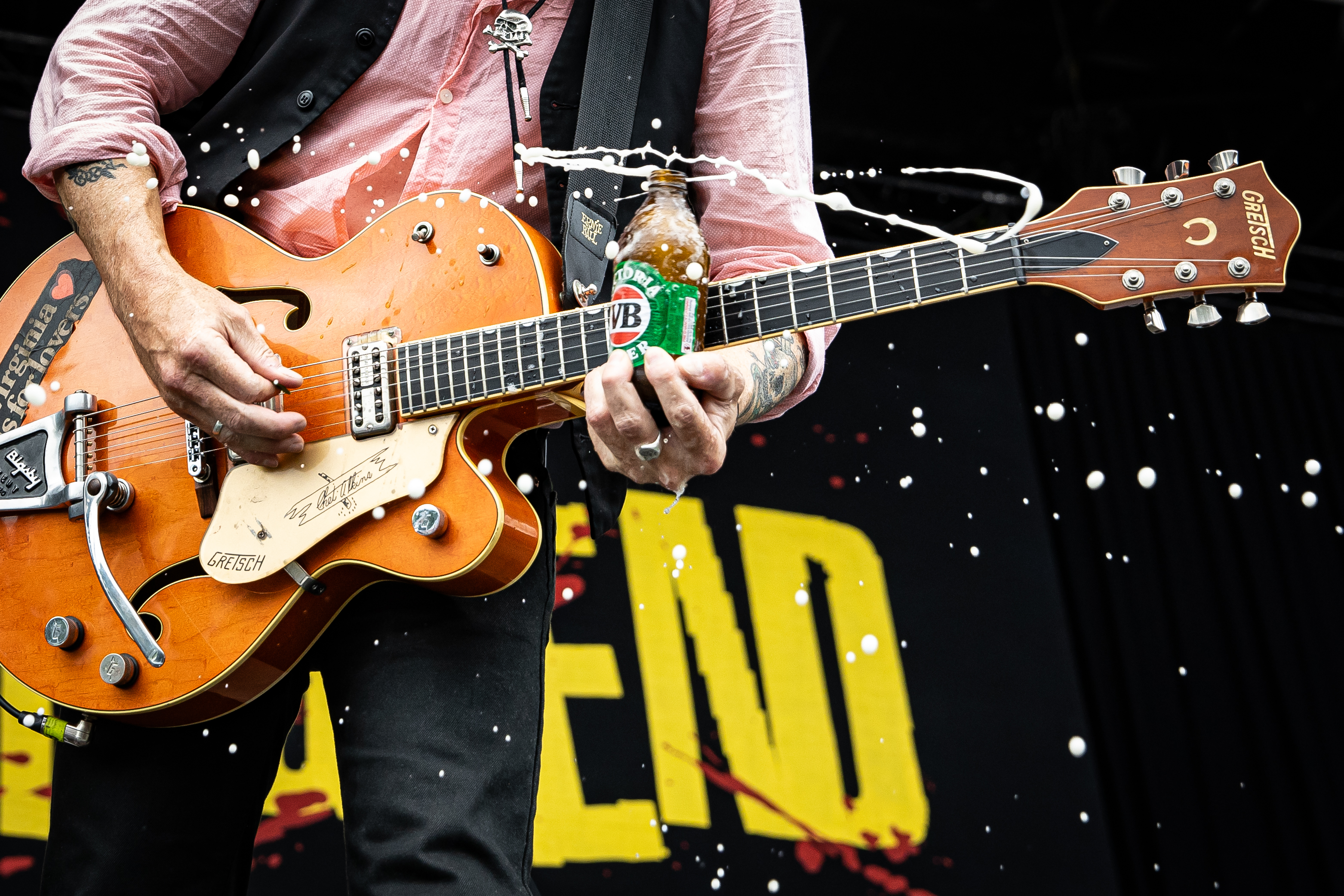

Speaking of guitar solos, you've long been associated with your White Falcon. You've been playing all your life, as an active working musician for at least 31 years. What excites you about picking up the guitar now? Do you still feel like there are things you can learn?

Sure. But I've probably gone the other way with this record. I've probably… not regressed in the way that I'm playing, but I've actually rediscovered the joy of the power chord. Just a bark. A lot of these songs were written with the emphasis on the right hand, just strumming fast, punk rock downstrokes, and hitting barre chords. Coming from the background I came from – which was the finger-picking thing, and I loved jazz guitarists, Charlie Christian, and people like Danny Gatton, like real proper players – I just wanted to rediscover the Sex Pistols and write an album where it was just primal, Neanderthal playing.

That was really refreshing to me, to play that kind of stuff. And when I was writing, not having anything that was too complicated again. If it got complicated I would banish it and get back to that kind of meat-and-potatoes thing. It was really liberating because again, it meant: is the song any good? There's nothing particularly fancy going on in the guitar department, so it was more "is it a good chorus?”. That always has to come first for me. I think that was kind of freeing: not trying to over-extend myself in the playing department, and playing [only] what the song required.

Are you still writing with the Gretsch? Are there any other guitars of late that you've picked up and grown fond of?

Half the record was written just on one of my Gretsches. I use a Tele a lot, some sort of '50s reissue, which I found was really great for just bashing away at. More often than not I'd be picking that up when I was writing songs, just plugging in – it sounds really gnarly – and just letting rip. As opposed to acoustic guitar and notepad, I would just bring out the beat and then riff away until I could hear something. The ball starts rolling from there.

It's an incredibly long process if I think about it, how you can start with just nothing and end up with an album: all the art work, the credits, the liner notes, the music, the production, the mixing. If you stop and think about it too much, you'd probably never get anything done.

Something out of nothing.

This is what we love about music. I can step in here one morning and three hours later walk out with the best song I've ever written. Where the hell did that come from? Or, walk out with nothing at all. There's no guarantee. It's a type of magic. Knock on wood – I'm so thankful that this batch of songs came at this time in my life, in the universe. You can push and push for a particular kind of song or record, but it doesn't necessarily mean you're going to get it. But I feel like this has reawakened something in me that goes back to those primal roots of the early days, and I feel like I was 20 years old again when I was writing these songs. I just had this perspective where I was making the right choices for the songs without over-extending or being too clever. One after another these songs kept coming up and before we knew it, we had 17 or 18 killer tunes. We went into the studio with Kevin [Shirley, producer] with that many songs, which was too many, so we had to be brutal about the ones that got cut.

I think it's understandable for people to feel sceptical when a group tries to tap into their very youth-centric origins. I was surprised by how well you've nailed it with this album, though. It's a belter.

Every band does that. They go, "Yeah man, we've made a record, it sounds just like our early stuff.” And you get so excited, you put it on, and you're just like… [disappointed gesture].

I do think this [new album] is like the big brother to that first record. It has that youthful energy. It's hard to put an actual word on what it is, but I suppose it's that thing that I feel The Living End had that was unique on our first record, and again that goes back to the first question: it's the background and all those different influences. I feel like this is the best version of us at this point. It's more similar to those first couple of records than anything we've done for the last 15 years.

Everything has changed so much since the '90s, and even since your last record in 2018. What are your thoughts on streaming services? In particular, what are your thoughts on this recent exodus from Spotify that some independent artists have enacted? These platforms are famously unjust in terms of what musicians get back, but on a corporate level their involvements are fairly hectic. Would you like to see The Living End removed? Will you stay?

It's such a tricky one, isn't it? We're not big enough where we can just retire and never have to worry about it again. We're still trying to get our music out there and expose it to people, for people to hear us. I think it's evil; I do think it's evil – but I don't know what the answer is and I need to probably do some more research on it. I've seen what's going on and I'm not fully across it like I should be, but I'm well aware of how bad it is for the artists. They're the ones that are suffering in this whole situation. Somehow they [the platforms] seem to be OK, and the record companies seem to be doing OK out of it, and it's the artists that are suffering. It's not right.

There should be a mass exodus, where if everyone was just off it all of a sudden, then they wouldn't hold the power that they have. We come from an era where we'd go gold and platinum on pre-sales alone – people were pre-ordering, going to shops… there was no other way to get it [the albums]. I struggle with it.

I guess it's such a valuable platform for people who aren't as established as us, who can get their music uploaded and heard by millions instantaneously. I don't know if that's a better world, though. I don't know if that's a better template or business model to what we used to have, but what we used to have is gone, so what do you do? You can't turn back the clock, but I completely understand why people are doing what they're doing.

Another big change is AI. Do you think it poses an existential threat to musicians? Can you imagine a future where people would want to listen to AI-generated punk rock?

Yeah, I can actually [laughs]. Unfortunately I can imagine that because nothing would surprise me. Nothing's shocking – it's all moving so fast. We're learning in real time, aren't we, and we're struggling to hang on. The whole world is trying to get a grip on it as it's happening.

I think that thing that people probably had a bit more of in the '70s and '80s, particularly in the rock and punk scenes, [was that] something had to be real, you had to believe it, like this is a real band. Like Springsteen, or the Pistols, were like "we're the real thing", or the Clash: "we're the only thing that matters". And the music papers, the NME and stuff, would write about it. Younger people don't care about that anymore. Life's moving too fast: they either like the song or they don't like the song. They don't care if it was recorded on a computer. That used to be the other thing: you can't record on Pro-Tools, it has to be on tape. Or you can't record on a Mac, you have to record through a '55 vintage Fender reverb or nothing. People cared. The idea of AI bands and stuff becoming wildly popular, I mean, I would just discount it.

Do you think that sense of music being a cultural glue is maybe becoming a thing of the past? Is that cultural engagement, a youth-centric one, a thing of the past?

Yeah, I think it's a thing of the past. If you think about what the last big song was that you remember everyone talking about, which is how it was when we were growing up: everyone would be vibing on a few songs that everyone knew. Something like 'Uptown Funk' where everyone was like that's a hit. Now you can have this huge song with this select group of people and then 20 metres away you can ask "have you heard this song?" and they'll be like "no, I've never heard it". We're all in different lanes, all vibing on different things. That's a wonderful thing, but the thing we love about music is that connection, that bringing people together. It's just a different world now. You can all just be vibing in different lanes.

I think it's time to jump completely into the heavy metal jacuzzi once and for all.

What were you listening to when you were writing this record? What were the records you were grabbing for during that process?

I was listening to a lot of punk rock stuff. My friend made me a playlist that had bands like RVG and Civic, sort of Aussie punk stuff. I'm into a bit of that, as well as going back to '70s punk, a lot of English stuff. Nothing too revolutionary, I was probably just going back to earlier influences I suppose and rediscovering my love of the simplicity of it.

That was one of the main aims when we recorded this: the songs had to be good, but it had [to come down to the] fact that when the three of us played it together it'd be enough. It's like Malcolm Young just playing an A chord: that's enough. It's not like "can he play an A diminished to 7". It's like, "no: just listen to the way that he is playing that chord". I feel like with songs like 'Roller' and 'Strange Place', the way the three of us will play, it will be enough.

Do you think there will be a 10th album?

Oh there has to be, yeah. I don't feel tired, I'm not sick of the band, I don't feel like we've come to the end of the road or anything. This feels like it's scratched the surface a little bit of what we could do for the next record, where we could take it even further. I still don't think we've made a really, really heavy aggressive kind of record. We've always had metal influences, but we've only dipped our toe in the water. I think it's time to jump completely into the heavy metal jacuzzi once and for all.

Make a thrash metal record.

Nothing is more fun for us than being in the rehearsal room and just shredding. We've always been like "ah no, we're a song band", but when we get on stage and play live, people would go "fucking hell, have you seen The Living End? They can really fucking play!". We're all about the songs, but I think it's about time we made that kind of record where all bets are off and it's just full-tilt impressive playing. That record needs to be made.

The Living End's I Only Trust Rock n Roll is out now through BMG. The 'I Only Trust Rock n Roll' tour kicks off in November, with dates below. Tickets are available at thelivingend.com.au

- November 8, The Fortitude Music Hall, Brisbane

- November 14, Hindley Street Music Hall, Adelaide

- November 22, Live at the Gardens, Melbourne

- November 29, Fremantle Prison, Fremantle

- December 12, Opera House Forecourt, Sydney

- This article will appear in Australian Guitar #165, which hits newsstands on October 20 2025. Subscribe and save via TechMags or iSubscribe.

Shaun Prescott is the editor of Australian Guitar Magazine. He has written across a variety of publications, including The Guardian, the Sydney Morning Herald, and Guitarist Magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.