All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

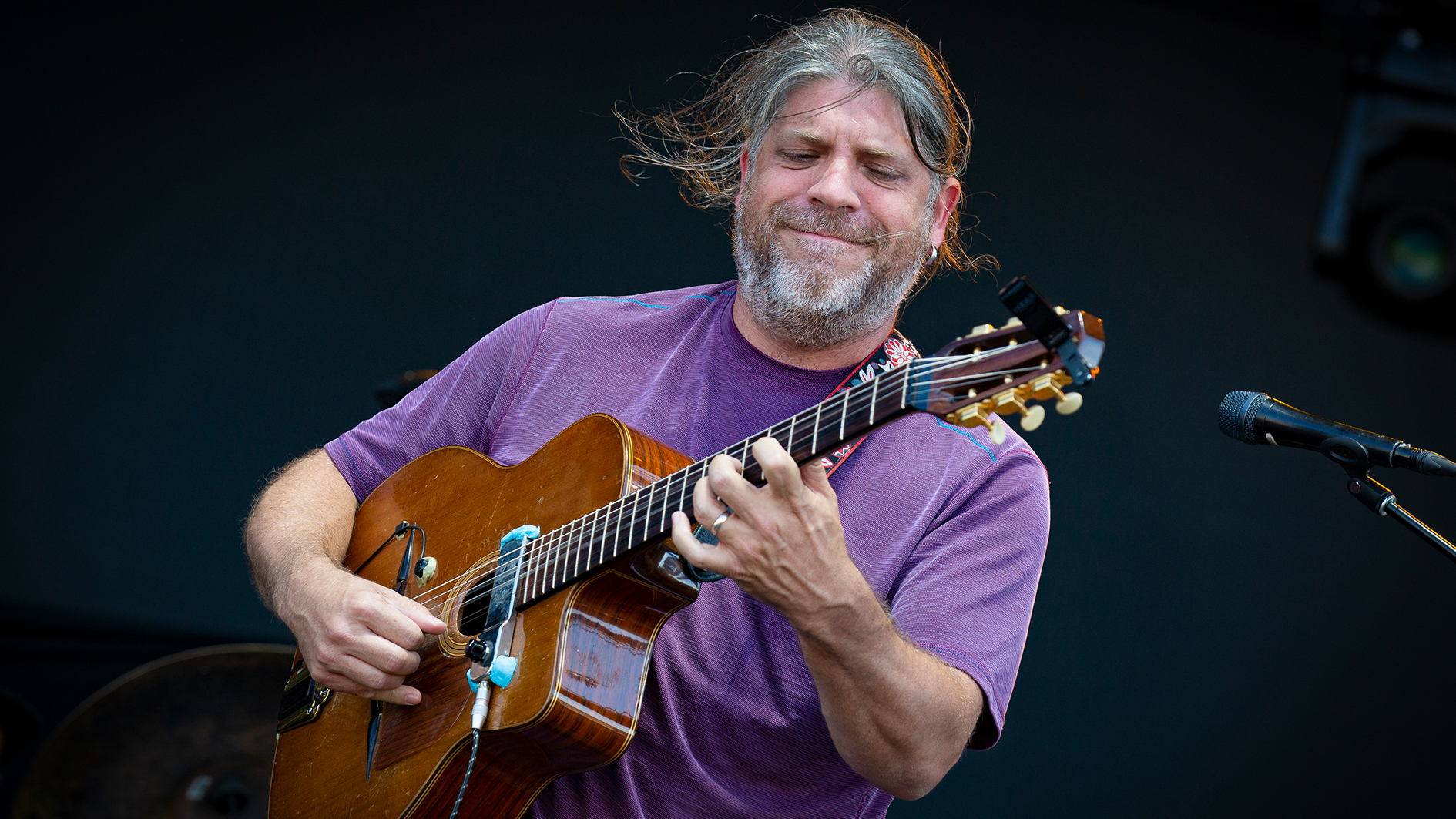

Fans of French guitarist Stephane Wrembel’s series of tribute albums to his idol, Django Reinhardt, have reason to celebrate: Earlier this year, he released a fourth edition of Django-inspired recordings titled - quite conveniently - The Django Experiment IV.

This coming January, right on schedule, he’ll release The Django Experiment V. When asked if he considers this latest volume to be the conclusion of the series, Wrembel laughs and says, “Oh, no. The last one will be when I die.”

David Gilmour, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, Andy Summers, Frank Zappa - those were the big guys for me. Even if I’m playing classical music, I try to put rock energy into it

During his career, Wrembel has released a host of albums that span genres such as jazz, blues, rock and flamenco, and he’s been an occasional collaborator on film scores for director Woody Allen, including 2011’s Midnight in Paris.

But he’s continually come back to his biggest muse as a source of inspiration, and when he says he expects to do “30 or 40 more” Reinhardt-infused records, people should take him at his word. “Django gives me an anchor,” Wrembel says. “I can do other things and put out different records, but every year I can come back to Django. It’s a cyclical thing, and there’s something almost transcendental about it; I don’t even think about what I’m doing. There’s no reason this can’t go on and on.”

Wrembel, who now lives in Maplewood, New Jersey, grew up in the same town where Reinhardt once lived (Fontainebleau, France), and he recalls the late guitarist’s music as something of a constant presence.

“You’d go out to pubs or restaurants, and there would be somebody playing Django,” he says. “It was always sort of there.” But Reinhardt wasn’t Wrembel’s first musical love; as a teenager, he was consumed by rock guitar. “David Gilmour, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, Andy Summers, Frank Zappa - those were the big guys for me,” he says. “I loved their energy and sophistication, and that stayed with me through the years. Even if I’m playing classical music, I try to put rock energy into it.”

It wasn’t until he moved to the States to study at Boston’s Berklee College of Music that Wrembel fell under Reinhardt’s sway. Transcribing classical and jazz compositions led to him writing out Django pieces, and in short order Wrembel came to understand the music that was always part of his DNA. “Django kind of bridged the worlds of classical and jazz, and that became the foundation for modern guitar,” he says. “Transcribing his music made me want to explore it further.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Famously, Reinhardt had full use of only his left index and middle fingers following a fire that burned more than half his body. To replicate the late guitarist’s technique as authentically as possible, Wrembel learned to play his songs with the same two-fingered fretting approach.

“You really understand Django’s genius that way,” Wrembel says. “It’s as if you see the guitar at its core, its root foundations. From there, everything unfolds like a spiral. Then when you go back to playing with four fingers, it’s like you’re playing another instrument.”

On The Django Experiment IV, Wrembel and his longtime collaborators - Thor Jensen (guitar), Ari Folman Cohen (bass), Nick Anderson (drums) and Nick Driscoll (saxophone and clarinet) - cut only one tune written by Reinhardt (Nuages); the bulk of the disc is comprised of jazz and blues songs that band members called out on any given recording day.

“That’s where the ‘experiment’ part of the title comes into play,” Wrembel says. “No matter what type of song we’re cutting - whether it’s something kind of film noir or even if we’re doing a version of Mongo Santamaria’s Afro Blue, we translate it to Django. His essence is in the room. It’s almost like, ‘How would he have played it?’”

When it comes to his guitars and gear, Wrembel has one adage: Keep it simple. For years, he’s played two Bob Holo-designed acoustics, each outfitted with a Stimer magnetic pickup from the 1940s (“They’re the same pickups Django used; they have so much character”) and an Ischell acoustic pickup, that he runs into a combination of an AER Compact 60 amp and a small Fender amp (“I don’t know which one it is; I got it for $100”).

That same philosophy extends to recording: Don’t mess with a good live take, and if a track contains some stray noises or string buzzing, so be it.

“We live in a time where everything is disgustingly clean,” Wrembel says. “People make music that is so polished. There are 500 edits in one song, and it sounds like elevator music.

We put the headphones on, and we play live. If the amp sounds dirty, leave it in. String noise? So what? You want to hear the life in a track. Listen to Wish You Were Here by Pink Floyd. In the beginning acoustic solo, you hear noises on the strings, the fingers moving around. That’s life. It’s reality. When you cut that out, you’re left without the physical aspect of what a musician does, and I just won’t have it. Not in my music.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.