How Jeff Beck changed guitar music forever

Guitar’s own Pablo Picasso, Jeff Beck was the guitar hero’s guitar hero, whose pioneering style hot-wired the instrument and made it succumb to his spell

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Whenever guitar players talk about ‘feel’, everyone will ultimately have their own interpretation of what exactly the word means. It’s an abstract and subjective term. However, most would agree that no player embodied ‘feel’ greater than Jeff Beck, the English virtuoso known as ‘the guitarist’s guitarist’.

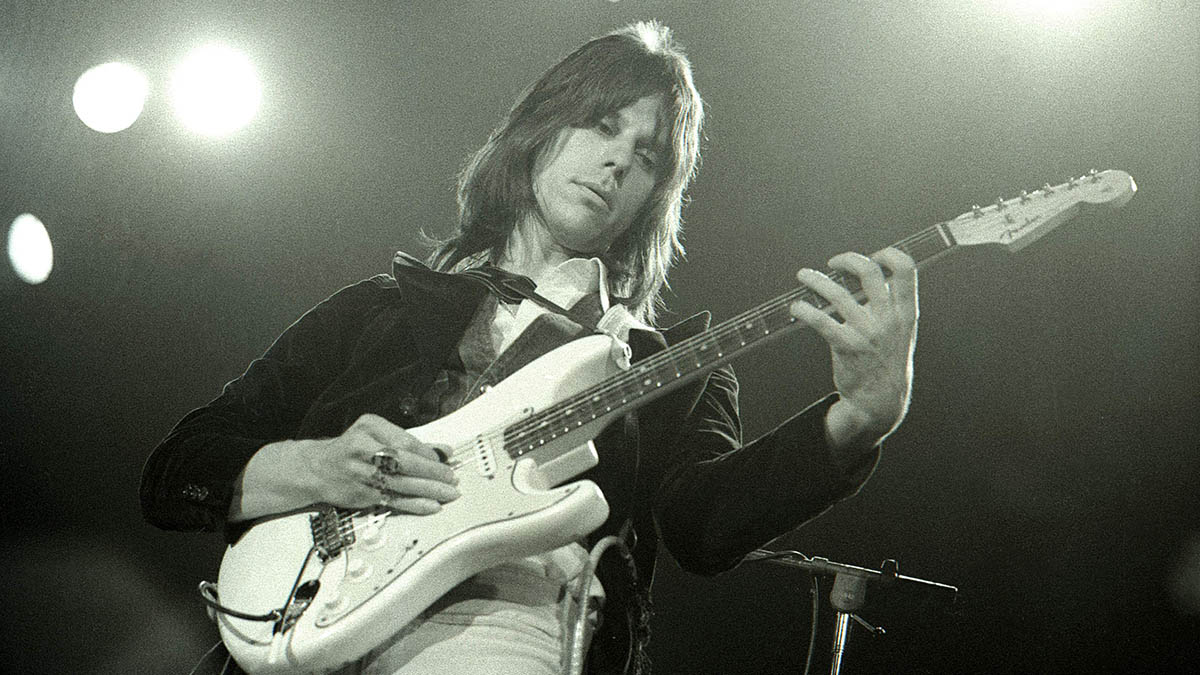

Whether you loved the fierce sound of his Telecaster in The Yardbirds, those early ‘70s conquests with a Les Paul in his hands, or the Strat magic he was most commonly associated with, Beck’s contributions to music of all kinds were simply incomparable.

His death on January 10, 2023, at the age of 78, is a profound loss to all who knew and loved him, and to all who were inspired by his playing and fearless creativity. And among the many tributes that followed his passing, each paying their respects to a musician who set the bar impeccably high, perhaps the greatest accolade came from Beck’s close friend and former bandmate, Jimmy Page.

“The six stringed Warrior is no longer here for us to admire the spell he could weave around our mortal emotions,” Page stated. “Jeff could channel music from the ethereal. His technique unique. His imaginations apparently limitless. Jeff, I will miss you along with your millions of fans.”

Innovator. Maverick. Genius.

Jeff Beck was all this and more. And as we look back now on his extraordinary artistic life, we begin with the moment that his path was set – when, as a young boy listening to the radio, he was transfixed by the sound of an electric guitar, played by none other than Les Paul...

The first guitar

He was born Geoffrey Arnold Beck on June 24, 1944 at 206 Demesne Road in Wallington, on the borders of South London and Surrey. And his love affair with the guitar began early, at the age of six, when he heard Les Paul and Mary Ford’s version of How High The Moon, prompting him to ask his mother about the slapback vibrations in between the vocals.

By the time he was 10, he was heavily into the sound of rockabilly guitar, idolising the music of Gene Vincent And The Blue Caps with a particular emphasis on guitarist Cliff Gallup’s contributions.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While learning to play on a borrowed guitar, he also experimented with building his own – gluing and bolting together cigar boxes with a fence post for the neck. For strings, he’d use thin wires from his model aeroplane collection, making tweaks and adjustments as he played through an old radio.

At the age of 16, Jeff landed an audition for The Bandits, who had a contract as backing group for singers impersonating the likes of Gene Vincent and Elvis Presley. To get the gig, he needed a proper instrument, and having pestered his parents for years, his wish came true in the form of a Guyatone LG-50 Strat copy.

In the early ’60s, while attending the Wimbledon College of Art, Jeff would become a prolific player on the West London scene, cutting his teeth in groups such as Screaming Lord Sutch And The Savages, Nightshift, The Rumbles and The Tridents. But this, of course, was just a taste of what was to come...

Jeff, Jimmy and Eric

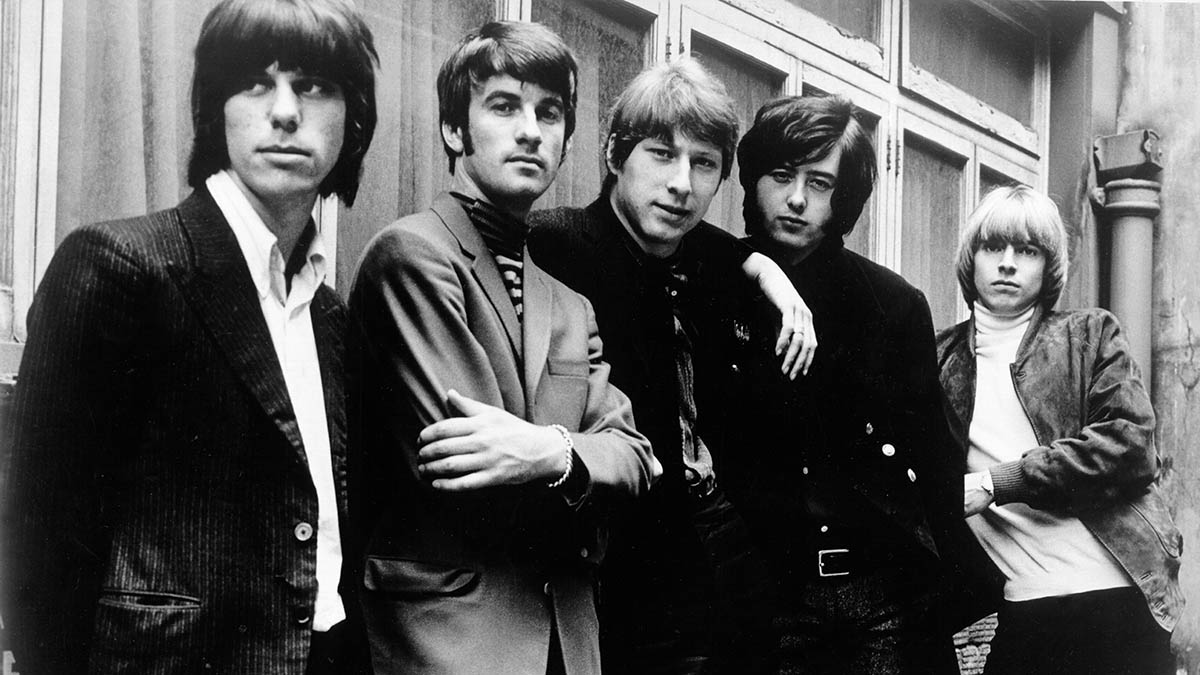

Beck rose to prominence in 1965 as the replacement for Eric Clapton in The Yardbirds – at the recommendation of Jimmy Page. Those three players would form ground zero of the British blues movement, fundamentally becoming the cornerstone of rock guitar. But both Page and Clapton would admit that Beck somehow had the upper hand, Clapton later referring to Beck as the world’s “most unique player”.

Beck’s brief 20-month tenure in The Yardbirds from March 1965 to November 1966 yielded the large majority of the group’s Top 40 hits. He appeared on debut studio album For Your Love, although Clapton was responsible for most of the guitar work, and by the time its follow-up arrived at the end of ’65 the tables had turned, with Beck appearing on more tracks than his predecessor, who by this point had exited.

The following album Roger The Engineer would be the only release to feature Beck alone on guitar and the only Yardbirds record to appear in the UK album charts, thanks to the success of psychedelic lead single Over Under Sideways Down.

It was around this time that Beck recorded an instrumental he named Beck’s Bolero, with Page on 12-string rhythm guitar, John Paul Jones (later of Led Zeppelin) on bass, Keith Moon of The Who on drums and Rolling Stones affiliate Nicky Hopkins on piano. “It was decided,” Beck recalled, “that it would be a good idea for me to record some of my own stuff – partly to stop me moaning about The Yardbirds.”

When Page joined Beck in The Yardbirds, the group had arguably the greatest guitar duo in rock ’n’ roll history. But this dream team was not to last. Beck was given his marching at the end of 1966, allegedly for missing dates on their US tour.

Digging in harder

Once out of The Yardbirds, Beck chose not to waste any time, releasing his debut single Hi Ho Silver Lining in 1967, with Beck’s Bolero – interestingly credited to Page despite the name – serving as the B-side.

With the wind in his sails, Beck recruited Rod Stewart on lead vocals and Ronnie Wood on bass as part of his backing band for his debut solo album Truth, recording once more with them for Beck-Ola, their 1969 debut as The Jeff Beck Group, before tapping up singer Bobby Tench, keyboardist Max Middleton and drummer Cozy Powell for two more albums under the same name. This line-up recorded 1971’s Rough And Ready and the self-titled album of the following year.

Although Beck was only in his early to mid-20s, these first major releases were concrete evidence that a guitar god had indeed arrived

Although Beck was only in his early to mid-20s, these first major releases were concrete evidence that a guitar god had indeed arrived. He was able to express himself articulately with a very distinct voice on guitar – digging in harder and pushing himself further than other players of that time.

Beck sounded meaner and angrier, bending harder and further, which only intensified his reputation as a hot-headed idealist. As he once explained: “I play the way I do because it allows me to come up with the sickest sounds possible... That’s the point now, isn’t it?”

Jeff and Jimmy

Beck’s Bolero, which he later stated was co-written with Page, features some of Jeff’s most highly regarded slide work – exploring soaring melodies, atmospheric glides and everything in between – as well as some heavy metallic riffing which prefigured what Page would create with the first Led Zeppelin album in 1969.

Other highlights from this stage of Beck’s career include two other tracks from Truth – Shapes Of Things, a reworking of The Yardbirds song, with incredible fuzzed-up leads, and a brilliant, wah-soaked version of Willie Dixon’s blues standard I Ain’t Superstitious. And from 1972’s The Jeff Beck Group, the weeping six-string orchestra heard on Definitely Maybe and, perhaps most notably of all, the more experimental ad libs at the very forefront of Going Down – a near seven-minute G-minor blues which saw him declare war on his whammy bar in the most mesmerising of ways.

Some might even say the guitar work was reminiscent of Jimi Hendrix, and Hendrix was another who held Beck in high regard, to the point where he borrowed a riff from The Jeff Beck Group’s Rice Pudding for his own song In From The Storm from Cry Of Love, the album he was working on in the weeks leading up to his death in September 1970.

In one of Beck’s final interviews, when asked about Hendrix’s homage to him, he said: “I can die happy.”

Breaking the rules

The greatest instrumental rock guitar albums may never have existed without Jeff Beck, such was his unwavering influence over the years. Have a think about your favourites – from Steve Vai’s Passion And Warfare to Joe Satriani’s Flying In A Blue Dream, as well as game-changing releases by Frank Zappa, Eric Johnson, Andy Timmons and Guthrie Govan.

They all owe a debt to Beck’s fearless attitude towards experimentation. “I don’t care about the rules,” Beck once said. “In fact, if I don’t break the rules at least 10 times in every song, then I’m not doing my job properly. Emotion is much more important than making mistakes, so be prepared to look like a chump. If you become too guarded and too processed, the music loses its spontaneity and gut feeling.”

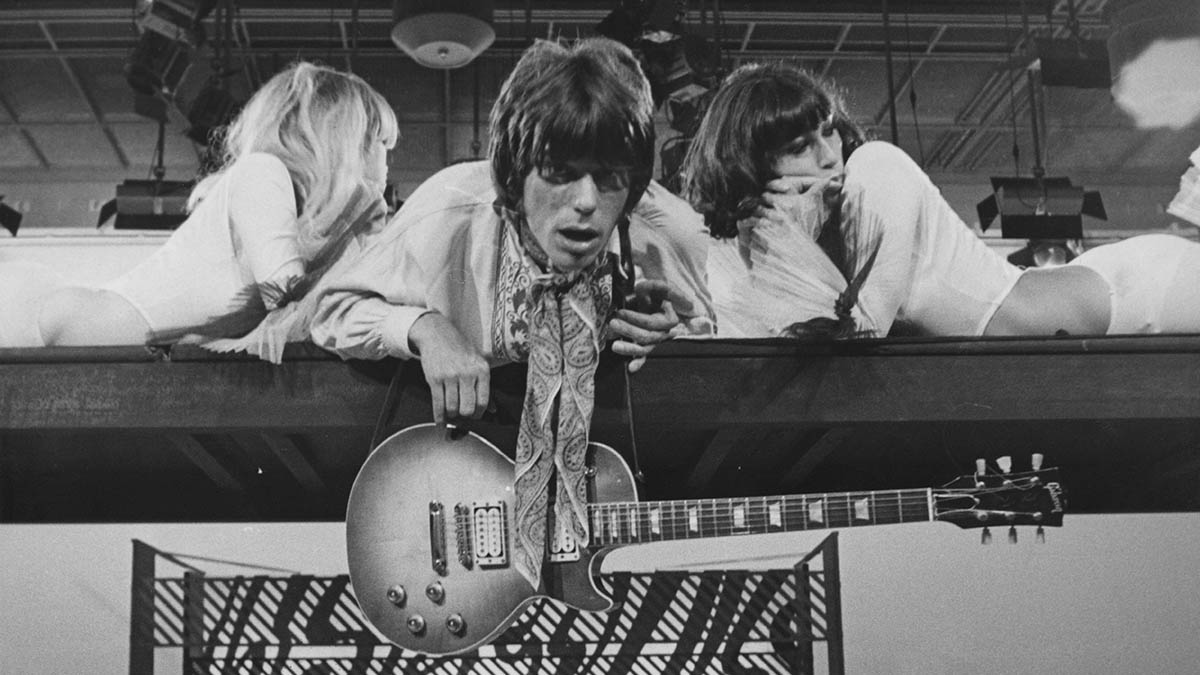

Beck had established himself as a force to be reckoned with early on, being privately considered and even auditioned by rock ’n’ roll heavyweights Pink Floyd and The Rolling Stones. But it was his second solo album, Blow By Blow, from 1975, that would arguably end up becoming his most defining release.

if I don’t break the rules at least 10 times in every song, then I’m not doing my job properly. Emotion is much more important than making mistakes, so be prepared to look like a chump

Jeff Beck

After he had split The Jeff Beck Group in 1972, his subsequent project was the supergroup Beck, Bogert & Appice, co-starring bassist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice, who had previously performed together in Vanilla Fudge and Cactus. The trio’s sole, self-titled album, released in 1973, drew more from the funk and fusion world than Beck’s previous recordings, particularly on tracks like Jizz Whizz and a version of Stevie Wonder’s Superstition.

Beck had played on the track Lookin’ For Another Pure Love from Wonder’s 1972 album Talking Book. In return, Wonder had agreed to write a song for Beck, and also to allow the Beck, Bogert & Appice version of Superstition to be released first, but the latter idea was nixed after Wonder’s label Motown sensed the potential for a hit. As an apology, Wonder gifted two songs to Beck for his Blow By Blow album – Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers and Thelonius, the latter on which Wonder would play clavinet.

In addition, as Beck plotted to take his creative vision to new levels, he enlisted producer George Martin, the so-called ‘fifth Beatle’, to produce the album, having been impressed by Martin’s recent work on Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Apocalypse. The results were astonishing.

The fusion-esque brilliance of opening track You Know What I Mean blurs into a reggae-inspired take on She’s A Woman by The Beatles – Beck using the same talkbox effect that he’d wowed crowds with during live renditions of Superstition with Bogert and Appice.

The Bag, a small unit made by Kansas company Kustom Electronics, was the first mass-market product of its kind, using a 30-watt driver in a speaker attached to a plastic tube held in the mouth, working like an artificial larynx – and in the process allowing guitarists to quite literally speak through their guitars, demonstrated by Beck jokingly telling his bandmates to ‘Get your shit together!’ via the pentatonic scale on the live version of Black Cat Moan. “It took me about three or four days to get some of the vowel sounds out,” he told Guitar World in 2009.

Amplified through a mic... it would just floor people. They’d go, ‘What the hell’s that?’ Then they’d see this sort of colostomy bag stuck to me. In fact, there was a review where the writer thought it was a bladder!”

Blow By Blow was also notable for being the last album made before Beck fully committed himself to the Strat. The ‘Oxblood’ Les Paul that he’d used as his main guitar – as seen on the cover art painted by John Collier – was actually a refinished 1954 Goldtop, with its original P-90s swapped out for full-size humbuckers and its neck made thinner.

The guitar had been bought from Memphis store Strings And Things, its original owner supposedly unhappy with the mods. In 2009, the Gibson Custom Shop made a limited run of 150 signature ‘Oxblood’ Les Pauls in the same dark brown finish, the first 50 of which were signed, numbered and played by Beck himself. “The Les Paul has a big powerful sound that no other guitar has – it just sounds rich,” he commented around the time of release.

But it wasn’t the only guitar heard on the album. The song Air Blower features some of the most exquisite creative surprises on the record, and given its out-of-phase tones and keyboard-like vibrato, a Strat must have been in Beck’s hands. Beck also revealed that Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers had been played on his 1959 Telecaster loaded with Seymour Duncan humbuckers, often referred to as his “Tele-Gib”.

Other key tracks included Scatterbrain, a darker take on the progressive fusion heard elsewhere on the album thanks to its menacing and meandering chromatics, and Freeway Jam, a heavy and psychedelic Strat boogie in G-minor, intensified by his Colorsound Overdrive going into a Marshall at full pelt.

By the time you get to the end of eight and a half-minute jazz noir odyssey Diamond Dust, you realise he’s slowly but surely taken you on a trip to a distant yet strangely familiar world.

All in all, it’s the kind of record that leaves a long-lasting impression every time you hear it. Bolstered by Beck’s youthful and at time playful bravado, it’s a magnum opus that can easily hold any listener’s attention, regardless of whether they play guitar or not.

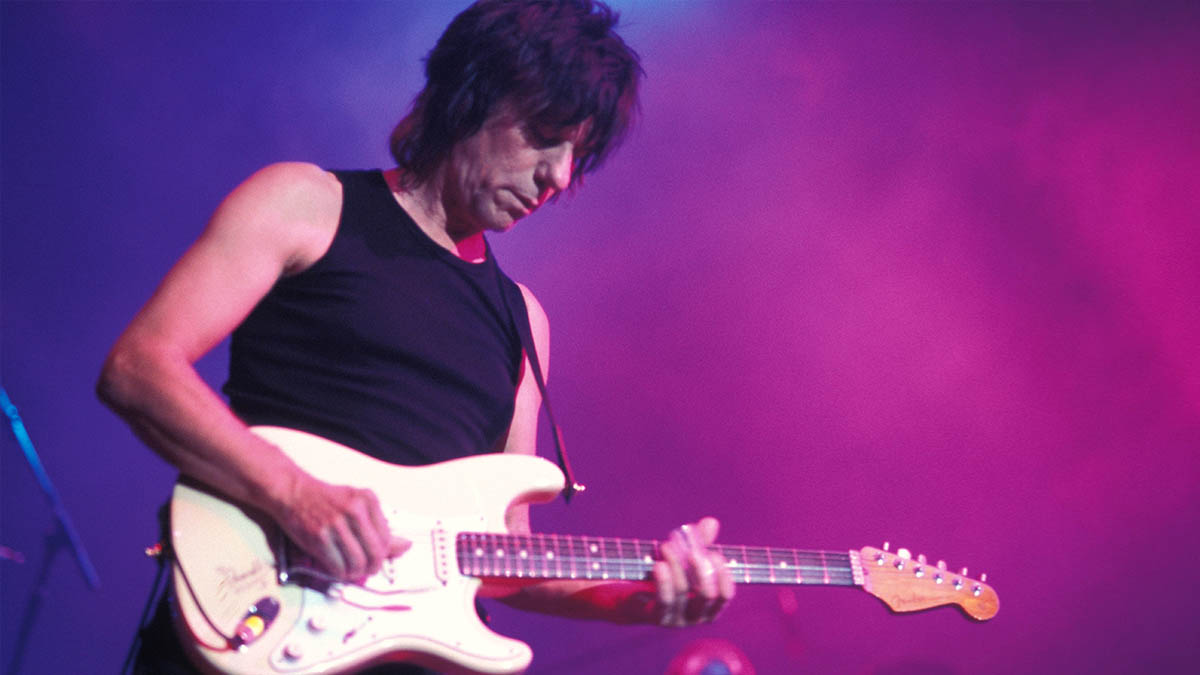

The Stratocaster

Beck’s third solo album, Wired, was released in 1976 as the follow-up to Blow By Blow, and is often regarded its a sister album. Produced again by George Martin, this also one of Beck’s most universally admired releases.

Interestingly, he didn’t write a single track on it – most of the credits going to newly recruited band members including drummer Narada Michael Walden, Mahavishnu Orchestra synth virtuoso Jan Hammer and bassist Wilbur Bascomb, save for a cover of jazz standard Goodbye Pork Pie Hat composed by jazz pioneer Charles Mingus in remembrance of saxophonist Lester Young.

I try to become a singer. The guitar has always been abused with distortion units and funny sorts of effects, but when you don’t do that and just let the genuine sound come through, there’s a whole magic there

Jeff Beck

At a time when it was common for guitar players to assume a mastermind role in their projects, let alone on their solo releases, Beck had a refreshing take on creativity – allowing his ears to dictate where the music came from with little concern for writing credits and massaging egos.

In his 2016 autobiography Beck 01 and 2018 documentary On The Run, he revealed that he had received a letter from Charles Mingus, praising his interpretation of the song. “Dear Jeff, it knocked me out to hear what you did,” Mingus wrote.

This track also had some interesting usage of effects, most likely a Maestro Ring Modulator and Octavia-style fuzz used sparingly to help give a lick or two their own distinctive voice – which was symptomatic of his attitude towards effects in general, with little used on the regular aside from wah, delay and reverb.

“I try to become a singer,” he revealed in 2010. “The guitar has always been abused with distortion units and funny sorts of effects, but when you don’t do that and just let the genuine sound come through, there’s a whole magic there.”

As opening gambits go, Led Boots is undoubtedly one of Beck’s finest – built around an up-tempo jam in G Mixolydian with more extreme whammy bar work, as teased by the Strat gracing the album cover this time round. The Oxblood Les Paul had now been relegated to the rear side of the sleeve and the tones at the heart of the music were noticeably brighter and slinkier.

From this point onwards, aside from dabbling with Jackson Soloists in the mid-’80s on fifth solo album Flash and his contributions to Tina Turner’s Private Dancer record, the Strat would serve as his primary conduit for musical expression, effectively becoming the voice he’d speak to the world through. “The Strat covers the complete spectrum of human emotion,” he once explained, noting how “the tremolo enables you to do anything, you can hit any note known to mankind”.

Come Dancing, the second track on Wired, is centred around a funk vamp going from D minor to Bb7, allowing Beck to occasionally deviate from D blues and into the Bb Lydian Dominant scale for a melodic minor twist. There’s also a lower octave effect that gets kicked in for the first solo, most likely coming from either a Mu-Tron Octave Divider or a Colorsound Octivider, and some heavy delay for the second lead section.

Composed by Jan Hammer, Blue Wind stands as one of the album’s more experimental offerings, starting off in G Lydian and then shifting into E Dorian blues, welding different techniques like country bends and natural harmonics into one truly unique musical statement. It sets the tone well for the album’s fusion-led second side, with six and a half minute epic Sophie taking the listener on a journey through the melancholic and subdued to high-octane thrills, before the heavily syncopated Play With Me tees things up for the breathtaking acoustic and piano-led closer Love Is Green.

Beck was often reminded how his two mid-’70s masterpieces were widely considered to be as good as it gets for instrumental guitar, but he remained humbly grounded throughout the course of his career. “Things turn out better by accident sometimes,” he once admitted. “But you can’t organise accidents.”

Always moving

By the end of the ’70s, Jeff Beck could have easily rested on his laurels. He certainly didn’t need to prove anything, yet he had plenty left to say. His fourth solo album There & Back, released in 1980, was also packed to the rafters with stunning fretwork. Highlights include the Jan Hammer-penned opening track Star Cycle, which sounded more electronic and futuristic, chronicling the excitement of a new decade soundtracked by advances in keyboard technology.

Then there’s The Pump, which witnesses Beck snake his way around the fretboard over a down-tempo vamp in E, switching over to Bb Aeolian for the key changes before returning back. Though it builds and builds over the course of its five minutes and 50 seconds, it’s a great example of how Jeff refused to overplay and was able to retain an air of suspense and mystery in moments where others would have been drawn out into the open.

Space Boogie, on the other hand, documents Beck at his rhythmically most urgent, providing a fitting contrast against the minimalist magnificence of outro The Final Peace.

Pure fingerstyle

Beck made only three solo albums in the 1980s, but he was highly prolific as a session guitarist during these years, lending his talents to recordings by Mick Jagger, Diana Ross and Malcolm McLaren, as well as rekindling his creative relationship with Rod Stewart – guesting on three tracks from the singer’s 1984 album Camouflage and Stewart repaying the favour on People Get Ready, the final single from Beck’s Nile Rodgers-produced Flash record.

It was also in this period that he decided to ditch the pick entirely, making the move from hybrid playing to purely fingerstyle – the earthy grit of skin on string quite literally putting him at one with his instrument, with no barrier in between. As he said at the time: “If you use a pick, you’ve got several fingers which are just redundant, they’re not doing anything, but with five fingers you can do all kinds of stuff.”

“The most beautiful guitar music ever recorded...”

While Flash was the sound of Beck returning to vocal-led music, save for two instrumentals – one of which winning the guitarist his first Grammy – its 1989 follow-up saw him going back the other way. To be perfectly honest, with a title like Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop and the cover art depicting him working on a giant Strat suspended from above like a mechanic, it could only ever have been centred around his unearthly guitar playing.

The album’s crowning moment would be the eerie masterpiece Where Were You, which saw Beck brazenly flaunting his innate control over the instrument – using the whammy bar to echo the fluidity of the human voice with infinite panache. The first time he strikes the D note on the 19th fret of his G string, it’s fretted as per the other notes in the sequence.

But every other D note is performed using the natural harmonic found in the exact same position, ultimately providing the seemingly endless sustain for his extreme pitchshifting on that final note – which sees him pulling up a whole step, then diving down a step and a half, returning to pitch, diving down one and a half, pulling up a whole step from there, then descending two whole steps and pulling to a step up from there. All served up in a glorious wash of reverb and delay, it’s easy to see why this quickly became a live favourite.

As Beck’s latter-era bassist Tal Wilkenfeld once told this writer: “He just sings through his guitar. Just listen to him playing Where Were You... that was always my favourite song in the set. I would just stand there on the side of the stage with my jaw on the floor every time.”

It’s a song that also made a long-lasting impression on Brian May, who recently referred to it as “possibly the most beautiful bit of guitar music ever recorded”, praising Beck’s “depth of emotion and sound and phrasing” and highlighting “the way he could touch your soul”.

Other talking points from the Guitar Shop album included Big Block – which, despite Beck distancing himself from the heavy metal movement, showcased one of his most forceful and thundering riffs – and Two Rivers, played completely using natural harmonics and the whammy bar for pitch-shifting and vibrato, somehow managing to champion simplicity and wild invention at the same time.

The daredevil

Arriving a whole decade after his previous solo album, 1999’s Who Else! was indeed worth the wait. Instead of stagnating in the same 12-bar format he started out with, or even continuing down the jazz-rock fusion sound he adopted from John McLaughlin, this album saw Beck reinventing himself as a contemporary artist. Which is why tracks like What Mama Said, Psycho Sam, Blast From The East and THX138 sound more like The Prodigy or The Chemical Brothers than the nostalgic yearnings of a rock ’n’ roll veteran from the mid-’60s.

Given his profile at this stage in his career, it can’t have been easy signing off on these tracks – doing things that his peers would never have dared to – but that’s precisely what made Beck such an artistic force, unafraid to gamble and taking risks others would have deemed too precarious.

This is also evident in his whammy bar technique, through which he would pull and push his way into infinity, with no real guarantee as to whether his guitar would still be in tune by the end.

Jackson Soloists aside, Beck chose to continue using Strats with a vintage two-point tremolo system long after the invention of the Floyd Rose, which was designed for players requiring tuning stability to compensate for all their extreme divebombs and harmonic screams.

While Eddie Van Halen, Joe Satriani and Steve Vai would harness these double-locking units with truly game-changing results, Beck chose to put all his trust in one of the earliest electric guitar designs and simply hope for the best. He was a daredevil in every sense of the term, unafraid of failure in his search for unique otherworldly greatness.

“I like an element of chaos in music,” he admitted in 2014. “That feeling is the best thing ever, as long as you don’t have too much of it. It’s got to be in balance. I just saw Cirque du Soleil, and it struck me as complete organised chaos. If I could turn that into music, it’s not far away from what my ultimate goal would be, which is to delight people with chaos and beauty at the same time.”

Perhaps the most enduring track from the Who Else! release is Brush With The Blues, a down-tempo shuffle in Bb minor in which he’d scoop in and out of notes almost as if his strings were made out of liquid, and gargling others by flicking the whammy bar, allowing it to warble like a ruler on the edge of a desk.

In many ways, it’s a track that encapsulates his genius better than any other, leaving the listener on the edge of their seat throughout its captivating six and a half minutes of improvisation, marvelling at how its architect is capable of pulling the most magical notes out of thin air.

When we talked about ‘feel’ at the very beginning of this tribute – well, look no further. Even this late in his career, 35 years on from joining The Yardbirds, he was releasing music that could very well have been his finest. Angel (Footsteps) is another fan-favourite and would end up appearing on many a setlist following its release, with the guitarist opting to say more with less using just a slide and all his higher frequencies rolled off. What he does play, however, is as magical as it gets.

The Pablo Picasso of guitar

At the dawn of a new millennium, Beck chose to up his game and release a lot more solo material than he had managed to in the decades prior. 2000’s You Had It Coming heralded yet more electronic experimentation, as evidenced on the drum ’n’ bass beats for key tracks like Earthquake, Nadia and Rosebud – again, showing how he was unafraid to take his guitar in new directions that no one else would have thought of.

This was followed by 2003’s ninth studio record, simply titled Jeff, which would see him win his fourth Best Rock Instrumental Grammy with the track Plan B.

It was around this time that Beck chose to revamp his signature Fender Stratocaster. The original model, in production from 1990 to 2001, featured a chunky U-shaped neck and Lace Sensor Gold pickups – two single coils in the neck and middle, plus a humbucking Dually in the bridge – available in Surf Green, Vintage White and Midnight Purple.

The second version, which was available from 2001 onwards and remains in production to this day, features a slimmer C-shaped neck and Fender’s Hot Noiseless ceramic magnet single-coils, with standard tone controls instead of the original model’s TBX circuit and coil-splitting functions, and the Wilkinson roller nut swapped out for an LSR equivalent. A Custom Shop model was launched in 2004 with identical specs to the 2001 revamp and also remains part of the Fender line.

Of his final albums, perhaps its 2010’s Emotion & Commotion that best demonstrates Beck going out on a high. It’s an album that saw him reaching far back into the past and finding beauty in songs that had nothing to do with guitar music whatsoever. His interpretation of Harold Arlen’s Over The Rainbow, originally written for Judy Garland in her starring role in the 1939 film The Wizard Of Oz, is emotive to the point where it would often reduce members of the crowd to tears when performed live.

His ability to reproduce the melody using the whammy bar and his fingers will forever be the very epitome of touch dynamics – showing just how much ground a guitarist can cover with one simple sound and living very much in the moment. The volume control would play a huge part in this, allowing him to roll back his lead tone into more subtle cleans and then back to full-fat overdrive whenever he saw fit.

Similarly, his heart-stirring rendition of Nessun Dorma, the aria from Puccini’s opera Turandot, most famously performed by Luciano Pavarotti, is a revelation in itself –highlighting a delicate vulnerability that had never been quite heard before. It’s no wonder Slash would often think of Beck as “the Pablo Picasso of guitar”.

Emotion & Commotion was also noteworthy for its usage of the female voice, with the likes of Joss Stone, Imelda May and Olivia Safe duetting with his own profoundly lyrical six-string melodies.

In fact, unlike the large majority of his peers, Beck had regularly championed younger female musicians, such as Canadian bassist Rhonda Smith (who also worked with Prince), Jennifer Batten (who played lead guitar on all of Michael Jackson’s world tours from 1987 to 1997) and Australian bassist Tal Wilkenfeld (who was barely in her 20s when Beck poached her from Chick Corea’s band).

In the 2018 documentary On The Run, Rhonda Smith noted how the guitarist had “a really cool knack” for picking female musicians “that go with his style and the type of energy that he wants to portray” and ultimately “the type of fire he wants to have”.

His last studio album as a solo artist, 2016’s Loud Hailer, saw him recruit Rosie Bones and Carmen Vandenberg from London group Bones UK – quite extraordinary given how both musicians were still in their 20s and fairly green while he was well on the way to his mid-70s after decades at the very top of his game.

His final recordings, released in 2021, would be for two tracks on Ozzy Osbourne’s album Patient Number 9, and the 18 collaboration with actor Johnny Depp, re-examining famous works by The Beach Boys, Killing Joke and Marvin Gaye. The fact he’d wrapped up a US tour with Depp little over two months before his untimely passing shows just how unexpectedly it came.

In the end, there is such sadness to think that never again will the world witness Jeff Beck play Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers or Brush With The Blues, furiously punishing his guitar in those transcendental airy moments after so beautifully caressing it. But we have to be grateful. He gave us so much. The world is well and truly in his debt.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).