“Space Guitar has to be heard to be believed. If one track could carve a path up to and beyond Hendrix, this is it”: The life and times of Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, the true guitar original who inspired Zappa and SRV – plus Ice Cube, Jay-Z and Mary J. Blige

From urban blues maverick to ‘Superfly’ funkster, Watson’s 40-plus-year career saw him negotiate his way through the most explosive period in musical history and, unlike so many, he managed to keep his ear to the ground and his music relevant to the times

John Watson Jr was born in Houston, Texas, on 3 February 1935. As a child he learned piano from his father, John Sr. However, like so many young Black kids coming of age in the mid-to-late 1940s, it was the mighty T-Bone Walker, best known for his iconic composition Stormy Monday, that grabbed his ears and made him want to be a guitarist.

T-Bone Walker’s influence over the subsequent course that blues and rock ’n’ roll took cannot be overestimated. A slew of great recordings from the late ’40s found their way into the hearts of everyone from B.B. King to Chuck Berry to Jimi Hendrix – and young Watson was no exception.

Johnny acquired his first guitar courtesy of his grandfather, a preacher, who agreed to let Jr have one on the condition that he “never use it to play the Devil’s music” – namely, the blues. After his parents’ separation in 1950, Johnny moved with his mother to Los Angeles and quickly became a feature of the LA blues scene, clearly ignoring his grandfather’s request!

By the age of 15, Watson was working regularly in the city’s juke joints playing both guitar and piano. He also took time to check out the jazz clubs, too, and heard giants such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

Later in life, Johnny mused that, at that time, jazz and blues were akin to two sides of the same coin. Musicians in those days embraced both equally and it was, effectively, recording studio contracts that determined whether an artist would grow to specialise in one or the other.

In 1952, aged just 17 and billed as ‘Young John Watson’, Johnny made his first recordings on piano for Federal Records. Songs such as Pachuko Hop and Motor Head Baby found Watson playing the typical driving R&B piano of the time.

Within a few years, however, the piano would be replaced by the guitar as the main instrument driving the rhythm along – and Watson would be right there at the heart of it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

1954 saw the release of the movie Johnny Guitar, a Western that starred Joan Crawford. After seeing the film, the artist formerly known as Young John Watson became Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson and, from that moment on, the guitar became Watson’s main mode of expression.

Then, out of the blue, came a track that can only be described as out of this world. Johnny was still only 19 years old when he recorded Space Guitar in 1954. Even today, it sounds extraordinary with the guitar tone changing from bone dry to reverb laden on a lick to lick basis.

Watson’s playing on the track is biting and aggressive yet full of humour and surprise. There’s even a swinging jazz chorus in there. Space Guitar really has to be heard to be believed. If one track could carve a path up to and beyond Hendrix, this is it.

Guitar first

The next few years had Johnny churning out a series of recordings built around his vocals and guitar. Although they’re fairly standard fare for the time – a lot of slow 12/8 blues and shuffles with a horn section à la T-Bone Walker’s output – it’s the guitar that stands out, as though somehow dropped into the mix from the future.

Johnny’s playing had a big influence on the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa and, later, Stevie Ray Vaughan

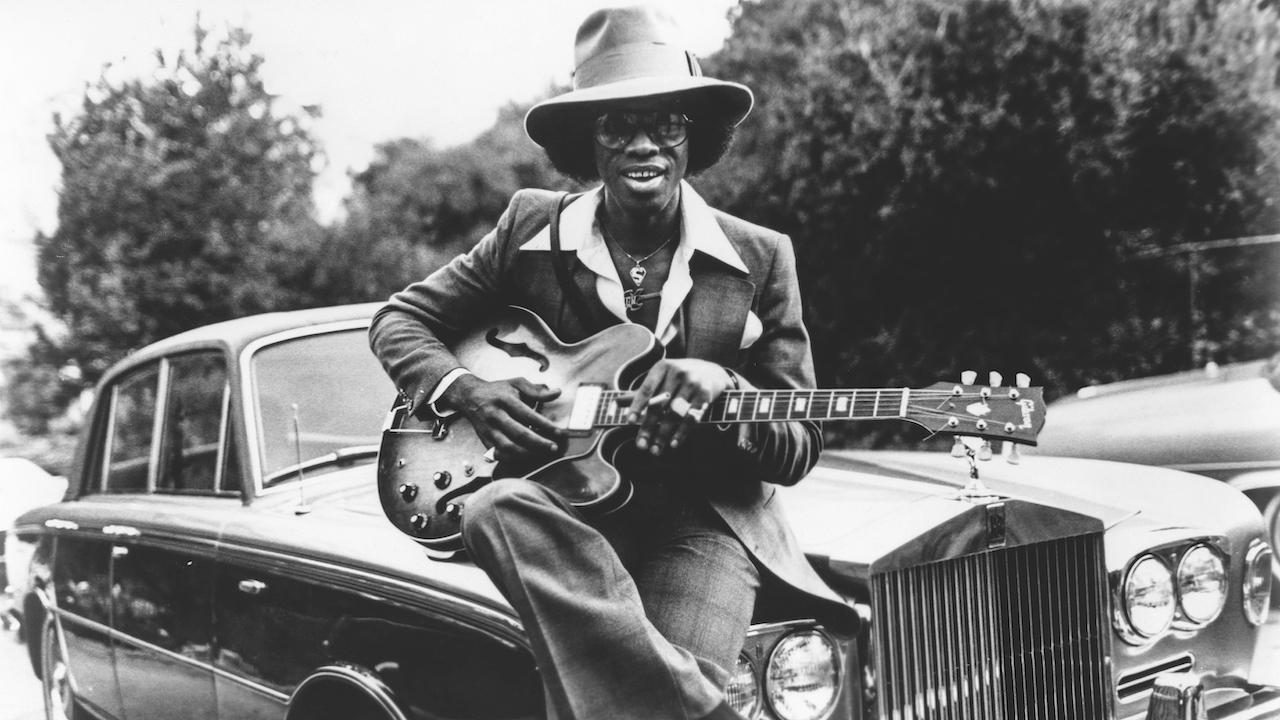

Playing a Telecaster by now, Watson’s approach and attack was ferocious for this pre-Jimi era. The licks he played are pure T-Bone Walker, often note-for-note, with Walker’s smooth tone, coaxed from a Gibson archtop, now replaced by a Tele and a cranked Fender amp.

Watson played without a pick, choosing a combination of thumb and forefinger instead. Listen carefully and you can hear the strings snapping against the neck as he plucked by pulling the string away from the fingerboard. There are no classical rest strokes here.

It’s said that Johnny would often have to change strings several times during a performance. Despite this seemingly brutal approach, however, there is a lot of subtlety at play in Watson’s music. His use of microtonal string bends and across-the-beat phrasing are quite beautiful when set against the gnarly overdrive that he employed.

Johnny always used a capo for key changes. He’d simply move it up or down the neck depending on what key the song was in and take it from there.

Many might see this as a cop-out, but there is a method going on here. It meant he would always be able to exploit an open-string sound, a sound he wanted. He wasn’t the only one to use this technique; both Albert Collins and Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown were also advocates of the capo.

Despite his seemingly brutal picking approach, there is a lot of subtlety at play in Watson’s music

Another Watson ‘quirk’ was to wear the guitar with the strap over the right shoulder. His hero T-Bone Walker did the same, as did Freddie King, Albert Collins and many others.

Watching videos of Johnny in concert seems to answer why he did it. He’d often take a solo then put his guitar down for his vocal. With the guitar on the right shoulder he could put it down or pick it up much quicker than if he wore it the way most players do.

There was also a showmanship element to this posture. Johnny would take the guitar off mid-solo and wave it around while still playing. He’d rest it on the stage and continue playing, too. Think of Hendrix playing with his teeth, behind his back, between his legs and how he’d sometimes play one-handed.

Brilliant and theatrical as it was, it wasn’t original. Those tricks had been employed by most blues guitarists since at least the invention of the amplifier and, without doubt, Watson was a master showman, even claiming to have “started that shit” when asked to comment on Jimi’s stagecraft.

Quiet influence

Johnny’s record label clearly tried everything to get a big hit out of him throughout the ’50s yet few of his many records scraped into the Top 40 of the R&B charts at the time. The label had him record everything from pop ballads to jazz standards, many of them focusing more on his fine singing voice than his guitar.

But despite this, his playing was being heard and he was having a big influence on the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa and, later, Stevie Ray Vaughan. Zappa cited the track Three Hours Past Midnight as the one that inspired him to pick up the guitar and repaid the debt many years later by inviting Watson to play on four albums between 1975 and 1985.

Two 1977 albums solidified his position as the “original gangster”, a reference to LP Gangster Of Love

As times and tastes changed into the 1960s, it seemed like Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson may have had his day. By now he was playing a Stratocaster and his self-titled 1963 album finds his guitar tone somewhat neutered. The album I Cried For You, also from 1963, finds him back on piano as he works his way through a set of jazz standards; the guitar was left at home for this session.

It does, however, show that he was a well-rounded musician who knew his jazz harmony and was much more than the pentatonic bluesman that he’s remembered for. Apart from a couple of other visits to the studio, though, that was pretty much it for Watson through the ’60s. He returned to the clubs and picked up jobs where he could.

By the early ’70s the blues boom that Watson had helped create was all but over. The Beatles were no more. Hendrix had tragically passed. Cream had gone their separate ways.

So many bands that shaped the sound of the ’60s on both sides of the Atlantic didn’t survive into the ’70s yet, somehow, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, a comparative relic from the ’50s, found a way to reinvent himself, finding a new sound and image that would serve him well for the rest of his life.

Funky time

In 1973 and approaching the age of 40, Watson released the album Listen. And he’d clearly been listening to what was going on. Funk and soul were evolving into what would become disco, and Johnny had the skills as a musician and producer to slot right into the centre of it.

Movies such as Superfly and Shaft helped to popularise this new take on funk. It was smoother, jazzier and more cerebral than the purely dance music it had evolved from.

Johnny’s guitar tone had cleaned up by now and he’d abandoned Fender for an array of Gibson models. From now until his death in 1996 he can be seen and heard with an SG, an ES-335, an ES-347 and an Explorer.

His playing had matured, too. The core was still firmly rooted in the blues, albeit with a more measured approach. Now, Watson’s new music allowed him to add some smooth octave runs and bebop licks into the mix along with some more complex harmony.

Johnny also self-produced his subsequent recorded output and often played many of the instruments himself, a feat which would be a huge inspiration for the likes of Prince and Lenny Kravitz. He had a knack for coming up with a killer riff that he would subsequently build a whole song around.

Etta James, of At Last! fame, said that Watson was a “master musician who could write a beautiful melody or a nasty groove at the drop of a hat”.

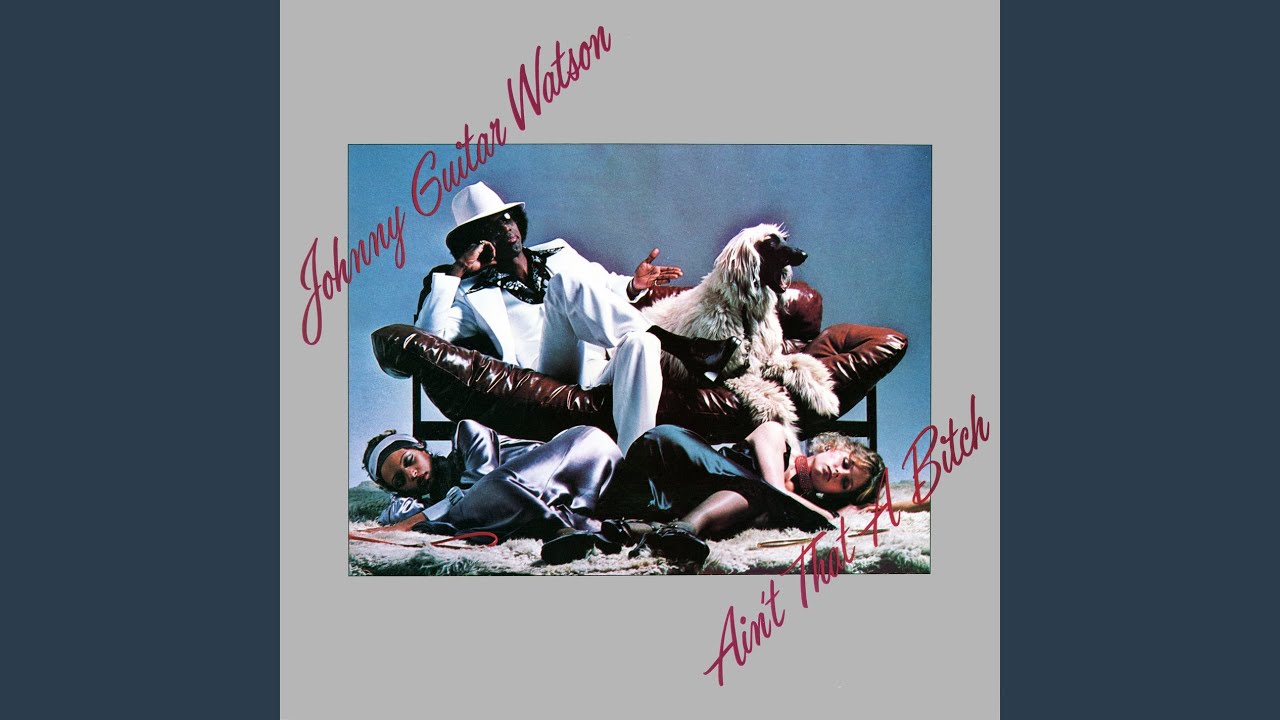

Still, a big hit eluded him. He again watched as others gained fame and fortune on the back of his inspiration. It wasn’t until 1976 with the release of Ain’t That A Bitch that he finally found success. The album went gold, selling over 500,000 copies as Johnny proceeded to deck himself out in broad-brimmed hats and sharp suits, all while sporting gold teeth.

Original gangster

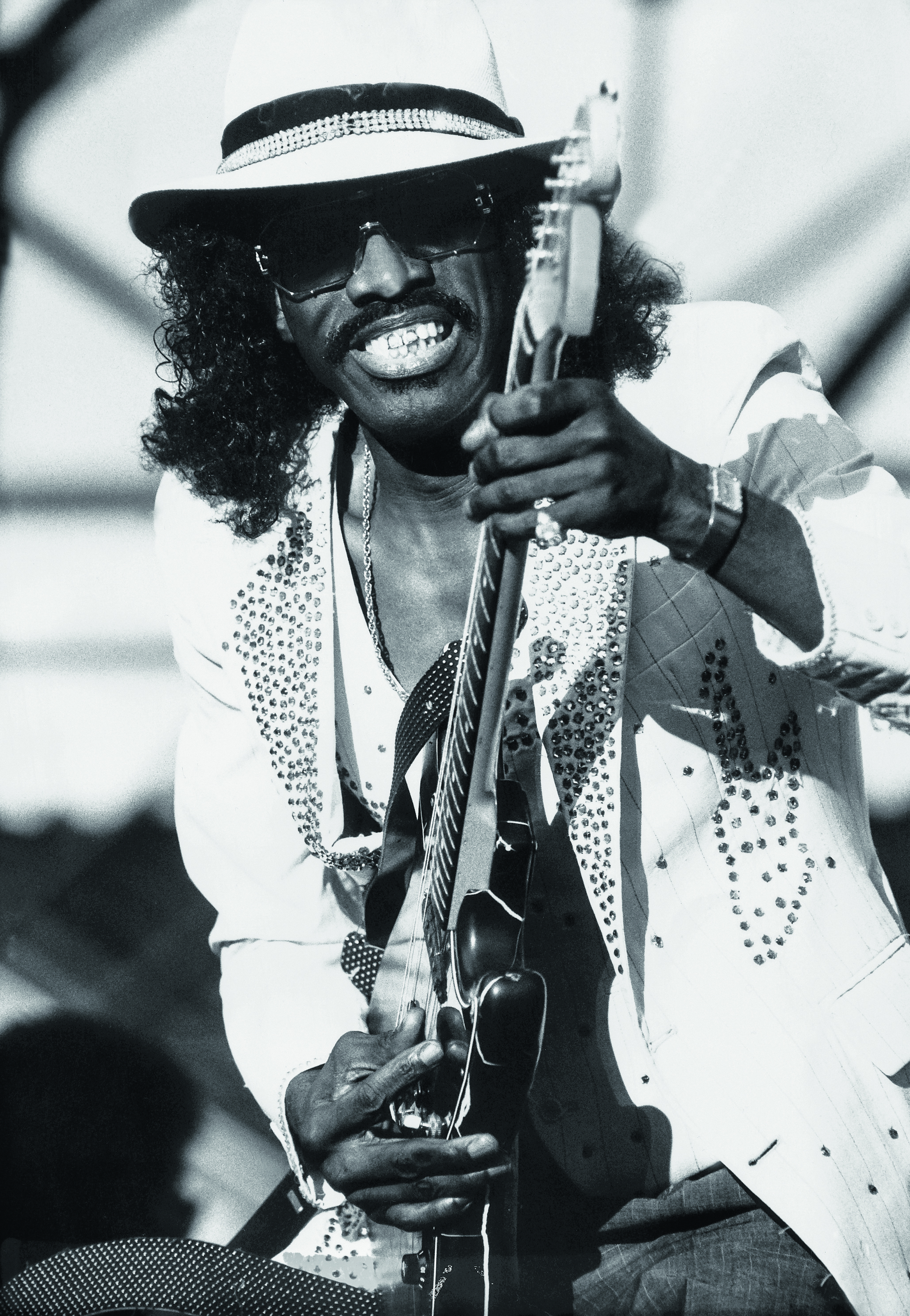

In 1977 two albums, A Real Mother For Ya and Funk Beyond The Call Of Duty, solidified Watson’s position as the “original gangster”, a reference to one of his most successful early records, Gangster Of Love.

These albums are laden with tight funk grooves accentuated by brass stabs. The lyrics are light hearted and humorous at times. The melodies are infectious with everything underpinned with some beautifully phrased and understated blues guitar, proving the point that blues doesn’t have to be loud to be deep.

Into the ’80s and ’90s Watson and his band toured extensively through the USA, Europe and Japan. Many concert videos exist and show a consummate professional at work with total command over his audience.

You can see the fun that Johnny and his band have on stage yet none of it compromises just how good the band is, with Watson out front taking everyone to the church of funky blues that he’d, by now, patented.

It was while on tour in Japan that Johnny collapsed and died on stage from a heart attack. His music didn’t die with him, though. He continues to influence guitar players to this day – without many of them knowing it.

Watson certainly deserves his place alongside T-Bone Walker, B.B. King and Jimi Hendrix as a true electric blues guitar pioneer, but there is another part to the story, as his music lives on through the likes of Ice Cube, Jay-Z and Mary J Blige who have all sampled his recordings for their own creations.

This proves the point that Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson was more than just a great and very important part of guitar history; he was, indeed, a master musician.

5 essential tracks (that aren’t Space Guitar)

1. Hot Little Mama

This track is as good as any of Watson’s mid-’50s recordings, demonstrating his driving blues licks borrowed from T-Bone Walker and updated.

2. I’m Gonna Hit That Highway

This great track demonstrates just what an influence Johnny would have on the likes of Jimi Hendrix.

3. Miss Frisco (Queen Of The Disco)

A fine example of how Johnny’s blues guitar fits seamlessly against a funk/disco backdrop.

4. Telephone Bill

A track that proves Watson was more than a bluesman. His solo here incorporates a lot of bebop/jazz language mixed in with his patent blues licks.

5. I Want To Ta-Ta You Baby

Fabulous jazzy blues from Watson’s funk years featuring some gorgeous blues guitar full of rhythmic and dynamic subtlety.

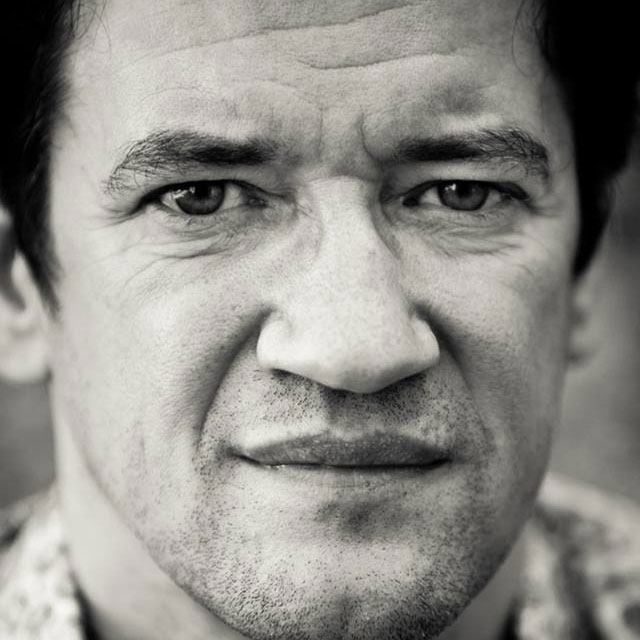

Denny Ilett has been a professional guitarist, bandleader, teacher and writer for nearly 40 years. Specializing in Jazz and Blues, Denny has played all over the world with New Orleans artist Lillian Boutté. Also an experienced teacher, Denny regularly contributes to JTC and Guitarist magazine and is founder of the Electric Lady Big Band, a 16-piece ensemble playing new arrangements of the music of Jimi Hendrix. Denny has also worked with funk maestro Pee Wee Ellis and is the co-founder of Bristol Jazz & Blues festival.