“While Les Paul may not have been the first to use tape for echo effects, he was certainly at the forefront”: The history of delay, from studio guitar reel-to-reel experiments to Line 6 and the rise of digital

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When we talk about echo, it might make you think of vintage effects, which may be dirty, distorted and lo-fi in character. In contrast, ‘delay’ started becoming the standard term when digital technology made it possible to manufacture cleaner and quieter-sounding effects with a full frequency range and longer delay times – as found on many modern delay pedals.

Whatever the nature of the effect, delay mimics something you might experience in a large empty building or a canyon. The time interval between a sound being generated and the sound that bounces back is long enough for the ‘echo’ to be heard as clear and distinct repeats.

Reverb is related, but these multiple repeats occur so quickly that the reflected sound is perceived as continuous, rather than something separate. Studio designers could build dedicated reverb chambers because the space required isn’t actually that great.

But tacking an echo canyon onto the back of a live room has never been a viable proposition… Consequently, echo effects didn’t become commonplace until technological solutions presented themselves.

Reel time

Looking back to the mid-1940s, the Allies returned from World War II having discovered Germany’s secret method for biasing analogue tape. Applying a high-frequency signal greatly expands tape’s upper frequency range, and it soon replaced acetate discs as the studio recording medium of choice.

Now, while Les Paul may not have been the first to use tape for echo effects, he was certainly at the forefront. He probably began experimenting during the 1940s, and his 1951 track The Whispering demonstrates how he was pushing the creative use of echo further than anybody.

It’s fairly simple to achieve tape echo. Most reel-to-reel machines have two or three heads, with one used to ‘print’ signal to tape, a second providing playback and a third offering higher quality playback for mixing purposes. When recording, the input signal is monitored, rather than the recorded signal.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Since the tape heads are physically separate, there will be a slight delay or ‘latency’ if the playback is monitored instead of the input. This delay time is determined by distance between the record and playback heads, and the speed at which the tape is running.

Let’s say the gap between the heads measures one inch and the machine is running at 15ips (inches per second). The delay here will be 1/15th second, which is 66 milliseconds. Double the tape speed and the delay halves, which is about right for automatic double tracking (ADT).

If tape speed is halved, the delay time doubles to 133 milliseconds, which provides the slapback delay that echoed all across the country, rockabilly and rock ’n’ roll records of the ’50s. With varispeed fitted to a tape machine, the delay time could be adjusted to match tempo, but it’s not critical with slapback echo.

For longer delays, two machines had to be used and a long ‘echo shelf’ was a common sight in control rooms

Delay times with a single machine will always be fairly short, so for longer delays two machines had to be used and a long ‘echo shelf’ was once a common sight in control rooms. With an extended tape loop or a reel of tape running between two tape machines, the first would ‘print’ the signal to tape and the second would play it back. Remarkably long delay times could be dialled in.

An engineer could use a stopwatch to estimate the track’s tempo and crunch the numbers to determine the spacing between the two machines needed for a quarter, half or full bar delay.

For fine-tuning, a kick or snare drum was sent to the tape loop and varispeed could be used to optimise the feel of the delay in the track. It was also possible to send some of the echo return back to the tape machines to achieve multiple repeats. When pushed hard, this induced feedback loops that span off into dub and psychedelia.

Tapes & Drums

When tape echo became ubiquitous, top guitar players, such as Chet Atkins and Scotty Moore, realised they needed a way to reproduce their studio sound in a live context. Electronics whizz Ray Butts, who later designed the Filter’Tron humbucker, provided the solution when he designed a guitar amp with an integrated tape echo that he called the EchoSonic.

Before long, standalone tape echo units became popular. The Maestro Echoplex owed a considerable debt to Ray and achieved classic status thanks to players like Neil Young, Jimmy Page and Eddie Van Halen.

Rather than vary the tape speed, delay time was adjusted by moving the playback head’s position. Meanwhile in the UK, WEM Copicats reigned supreme. These units were especially popular among fans of The Shadows, despite the fact that Hank Marvin used a Meizzi Vox Tape Echo.

Into the ’70s, Roland introduced various Space Echo and Chorus Echo units that set new standards. Like some earlier designs, they had multiple playback heads that could be used individually or in combination for complex ambient effects. With varispeed and built-in spring reverb, these units boasted fans including Brian Setzer and Adrian Utley (who today favours the RE-202).

Like most gear from the pre-digital era, echo devices started out with valves, before moving over to discrete transistors and op-amp chips. Many players prefer the solid-state circuits and use tape echo devices to push their valve amps into overdrive. The Echoplex circuit is especially popular, and several modern stompbox boosts use the preamp design without the echo effect.

David Gilmour is one of the great exponents of delay and in his earlier years he favoured the Binson Echorec. Employing a rotating magnetic drum, rather than tape, they sound glorious, but Binsons are notoriously temperamental.

Wowed & fluttered

Unlike studio-quality reel-to-reel tape recorders, most standalone tape echo units are loved for their flaws as much as their virtues. There are exceptions, but most have a limited frequency range and all distort to some extent.

Depending on the design, irregular maintenance or wear and tear, some tape echoes struggle to run at a consistent speed. This induces an irregular pitch fluctuation called wow and flutter, and provides a distinctive vibrato that many players enjoy.

Less popular is the thump of the tape splice as the loop passes the head. This is one reason that Echoplex and Roland devices employed very long tape loops housed in an enclosure. Roland loops can last several years before they need replacing, and Echoplexes operate with plug-in tape cartridges that are easy to replace.

Bucket brigade

Vintage tape echoes are not without their drawbacks. There’s the inconvenience of lugging around extra gear, continual head cleaning and demagnetising, and inevitable servicing expenses. No wonder guitarists were looking for easier options by the ’70s.

Help arrived in the form of the bucket brigade device (BBD), which is an integrated circuit comprising numerous capacitor cells. Packets of charge can be transferred from one capacitor to another, and the time lag for every transfer creates the delay. The process is often likened to a row of firefighters moving water by transferring it from one bucket to another. Hence the term ‘bucket brigade’.

In order to minimise distortion and maintain a good signal-to-noise ratio, the input signal must be compressed and troublesome high frequencies filtered out. A clock governs the transfer speed, and after the delay processing, clock noises are filtered out before the delayed signal passes through an expander to be mixed into the dry signal.

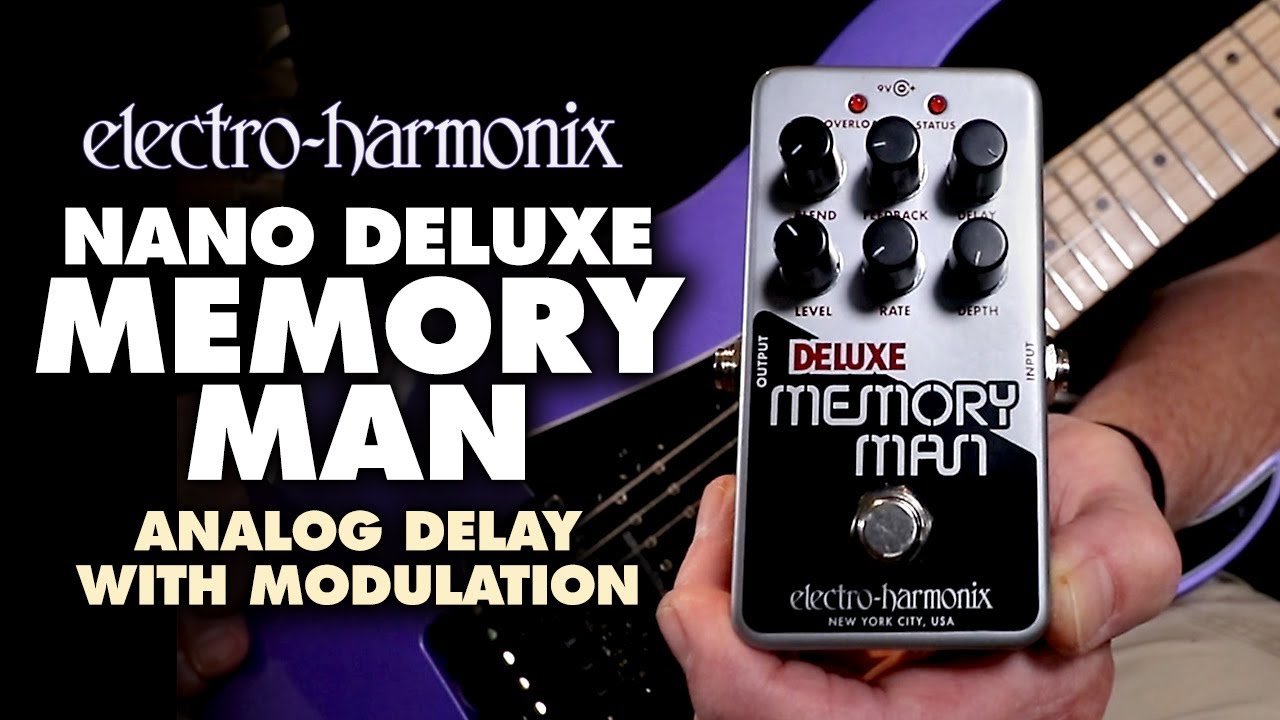

BBD delays are hardly hi-fi devices and create delay effects that resemble tape and drum echo, minus the pitch modulation. But they require no maintenance and are significantly smaller and lighter. Classic examples include the Boss DM series, Ibanez AD9 and lifelong favourite of U2’s The Edge, the Electro-Harmonix Memory Man.

Rack ’n’ Roll

In any digital recording system the first stage converts the analogue signal into data for storage. When it’s needed, this information is retrieved and converted back to analogue with no discernible distortion or signal degradation. Since the data can be stored indefinitely, there’s the potential for extraordinarily long delay times.

Most digital delays display the delay time, and with so much music being recorded to the grid, it’s easy to dial in settings that perfectly match the track’s tempo. Every professional engineer once carried a delay chart in their Filofax, but these days you can Google ‘BPM to delay chart’ instead.

With such clarity and precise control, multiple delays became commonplace in mixing because things didn’t degenerate into sonic soup. Instead, lush atmospheric textures could be created and producer Daniel Lanois is a recognised master of the art. Classics of the era included the Bel BD 80, TC Electronic 2290 and the AMS DMX1580S.

Rack-mounted delays became commonplace in ’80s guitar rigs and were generally connected via effects loops. Precision delays allowed guitarists to generate complex rhythmic patterns from the simplest of ideas that could ping-pong between loudspeakers. The Edge is perhaps the most well-known exponent of this playing style.

Bouncing back

Far from being anachronistic, vintage-style echo has never been more popular. In large part, that’s because digital modelling technology is so often directed towards recreating classic equipment.

Most DAWs come with native tape echo plug-ins, and some of the Audio Unit studio delay and tape echo emulations combine accurate sounds with precise digital control of delay times, distortion and pitch modulation.

Digital delays in stompbox form began appearing during the 1980s, but they were largely functional, rather than characterful. Things really got interesting when Line 6 introduced the DL4 Delay Modeler with its smorgasbord of classic delay models, ergonomic controls and tap tempo.

That set the tone and these days you can buy a Space Echo, Echoplex, Binson or Eventide in stompbox form. Some are actually made by the original manufacturers, with tonal characteristics and looks that are in keeping with the originals.

Or how about a digitally controlled tape or drum echo that will fit on a pedalboard? Whatever your preference, we’re swamped with choice.

Huw started out in recording studios, working as a sound engineer and producer for David Bowie, Primal Scream, Ian Dury, Fad Gadget, My Bloody Valentine, Cardinal Black and many others. His book, Recording Guitar & Bass, was published in 2002 and a freelance career in journalism soon followed. He has written reviews, interviews, workshop and technical articles for Guitarist, Guitar Magazine, Guitar Player, Acoustic Magazine, Guitar Buyer and Music Tech. He has also contributed to several books, including The Tube Amp Book by Aspen Pittman. Huw builds and maintains guitars and amplifiers for clients, and specializes in vintage restoration. He provides consultancy services for equipment manufacturers and can, occasionally, be lured back into the studio.