“It’s all about the patterns that smoothly and musically ‘walk’ you from one chord to the next”: Sue Foley shows you how to nail blues turnarounds

In my previous “Blues You Can Use” columns, I focused on what I consider to be essential rhythm guitar and accompanying single-note patterns that exemplify Chicago-style blues guitar, as heard in the playing of blues greats like Jimmy Rogers, Eddie Taylor, Luther Tucker, and Robert Lockwood Jr.

This time, we’ll focus on the “turnarounds” that fall within the last four bars of a standard 12-bar blues progression.

To review, the first four bars in a 12-bar blues are either made up of the I (one) chord, which is the home key or “tonic,” or are built from one bar on the I chord, one bar on the IV (four) chord, and then two bars on the I chord. Bars 5 and 6 move to the IV, and bars 7 and 8 return to the I chord.

The last four bars, 9-12, are one bar on the V (five) chord, one bar on the IV, a bar and a half on the I and, finally, by two beats on the V chord, to set up the next 12-bar chorus.

When playing over bars 9-12, it’s all about the “turnarounds,” which are patterns that smoothly and musically “walk” you from one chord to the next.

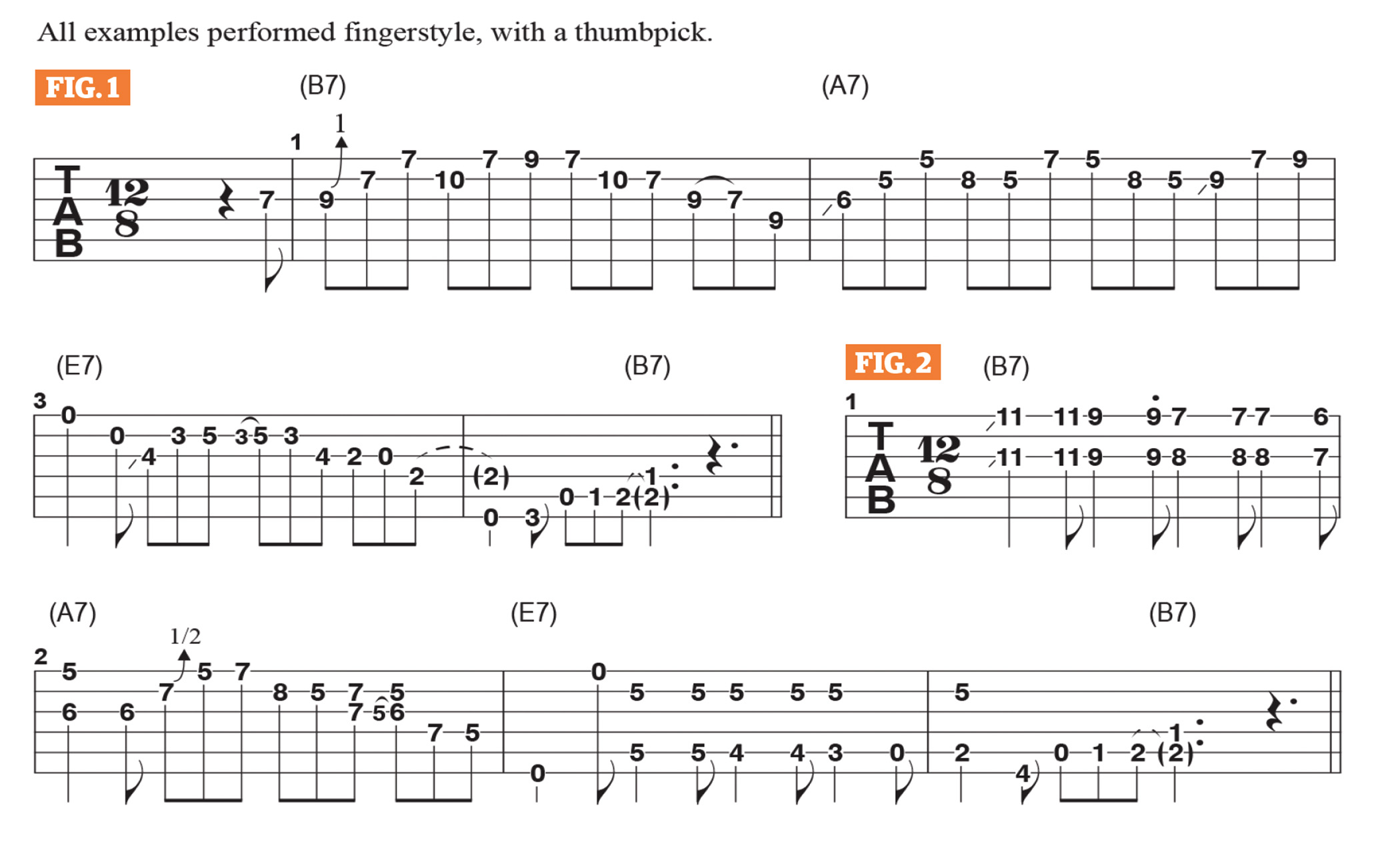

In Figure 1, the pattern begins over the V chord in the key of E, B7, and uses notes from the B minor pentatonic scale (B, D, E, F#, A) with the inclusion of the 9th, C#.

In bar 2, the pattern moves down to the IV chord, A7, and is essentially based on A minor pentatonic (A, C, D, E, G) with C#, the major 3rd, played in the place of C, the minor 3rd. Notice that the shape of the melodic line is nearly identical over both chords; that is why I think of these riffs as patterns, as opposed to being scale-based.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

At the end of bar 2, I slide up to G#, followed by B and C#, and these notes anticipate the move back to the I chord, E7, in the next bar. This phrase is based on the E minor pentatonic scale (E, G, A, B, D), and we end with a “walk-up” to the V chord, B7.

Figure 2 offers another way to navigate through the V - IV - I changes: I begin with double-stop 6ths – pairs of notes that are the interval of a major or minor 6th apart – over the B7 and land on an A7-type double-stop in bar 2.

On beat 2 into beat 3, this is really an E7 lick that moves to an A7 lick on beat 4, and the example ends with a standard E7 turnaround, with a high E note fingerpicked together with a chromatically descending bass line D, C#, C, B.

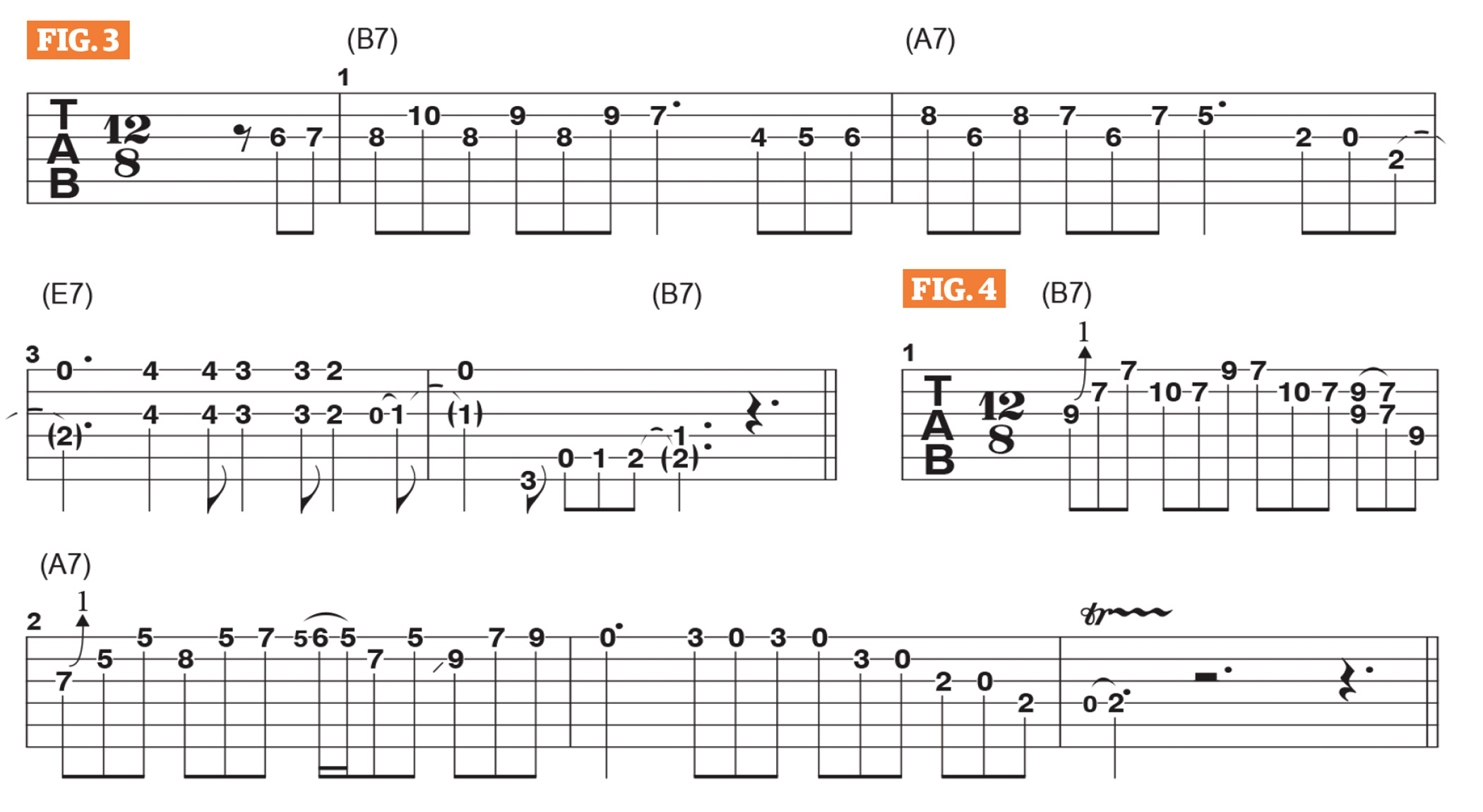

Figure 3 focuses on the walk-ups that set up the B7 chord – C#, D, D# –and A7 – B, C, C#. The figure ends with chromatically descending double-stop 5ths sounded on the 1st and 3rd strings.

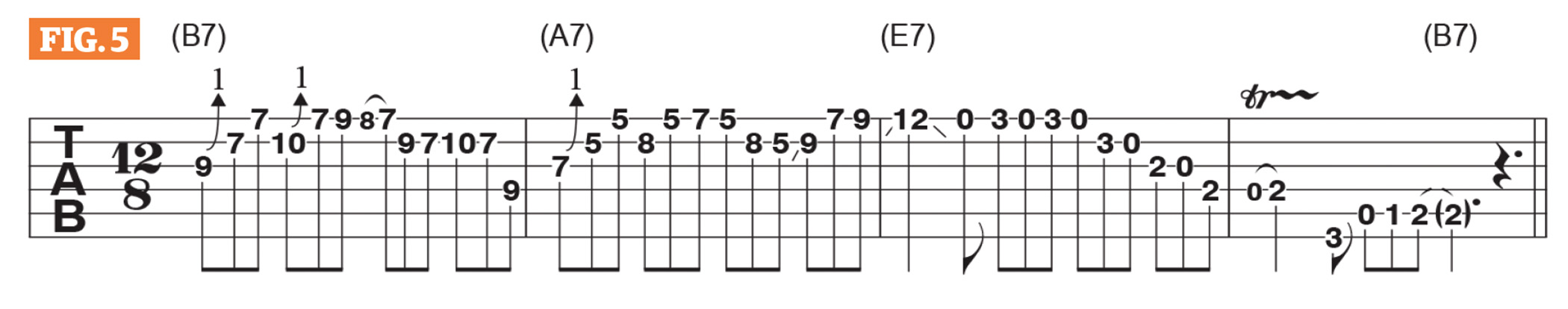

Figures 4 and 5 offer two more variations, featuring whole-step bends at the start of the B7 and A7 chords, respectively. Notice that both figures illustrate different melodic connections as you move from one chord to the next.

As I stated previously, this type of playing was developed in ’40s and ’50s Chicago blues, as players moved to electric guitars and began playing more single-note lead lines. I find these phrases to be very multi-functional.

When soloing, it’s great to have lines like these that ground and “center” your playing on each chord in a very effective and musical way.

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.