“A twist for the fingers as well as the brain”: Players like Steve Hackett are masters of extended chords/harmony – here’s how you can use them too

Today in extended chords 101, we look at 11th chords – both minor and major – and explain how these “harmonically dense” voicings look on the fretboard

The world of extended chords can appear quite unfathomable at times. The apparently benign 11th chord is a great example of this, as it falls between the cracks of many chord-naming conventions, inhabiting a world of its own.

As you may know, extended chords go beyond the basic major or minor triad, adding the 7th (or b7th), 9th, 11th, and finally the 13th. In music theory books, this usually happens neatly in ascending scale order, and we hear increasingly beautiful, complex chords as we go.

However, chords can become a little too ‘dense’ harmonically once we get to those 11th and 13th extensions, so the 3rd and 5th are very often omitted.

Add this to the fact that we can’t physically play that many notes at once on the guitar (let alone in scale order…), and you will see that we need to carefully think about what we can do without, while still meeting the theoretical requirement of such chords. See the examples for further explanation!

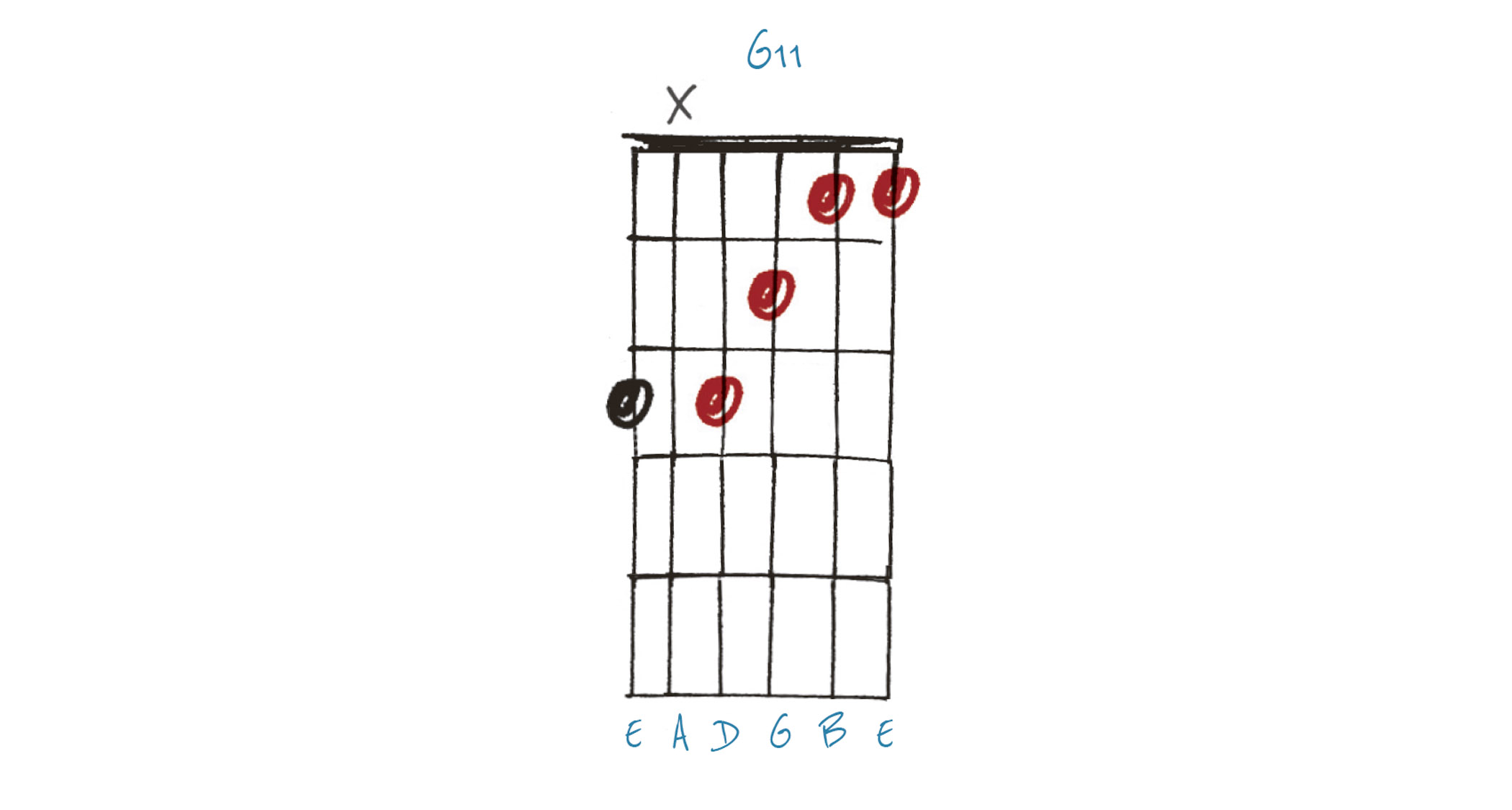

Example 1

G11 is a movable example of how such chords are arranged. In theory, a G11 chord would contain Root-3rd-5-b7-9-11, or G-B-D-F-A-C, in the key of G. It fairly successfully includes all notes (from low to high): Root (G)-b7th (F)-9th (A)-11th (C). The F on the first string is a duplicate b7. For practical and harmonic reasons, the 3rd (B) is omitted. Sometimes this is called F/G.

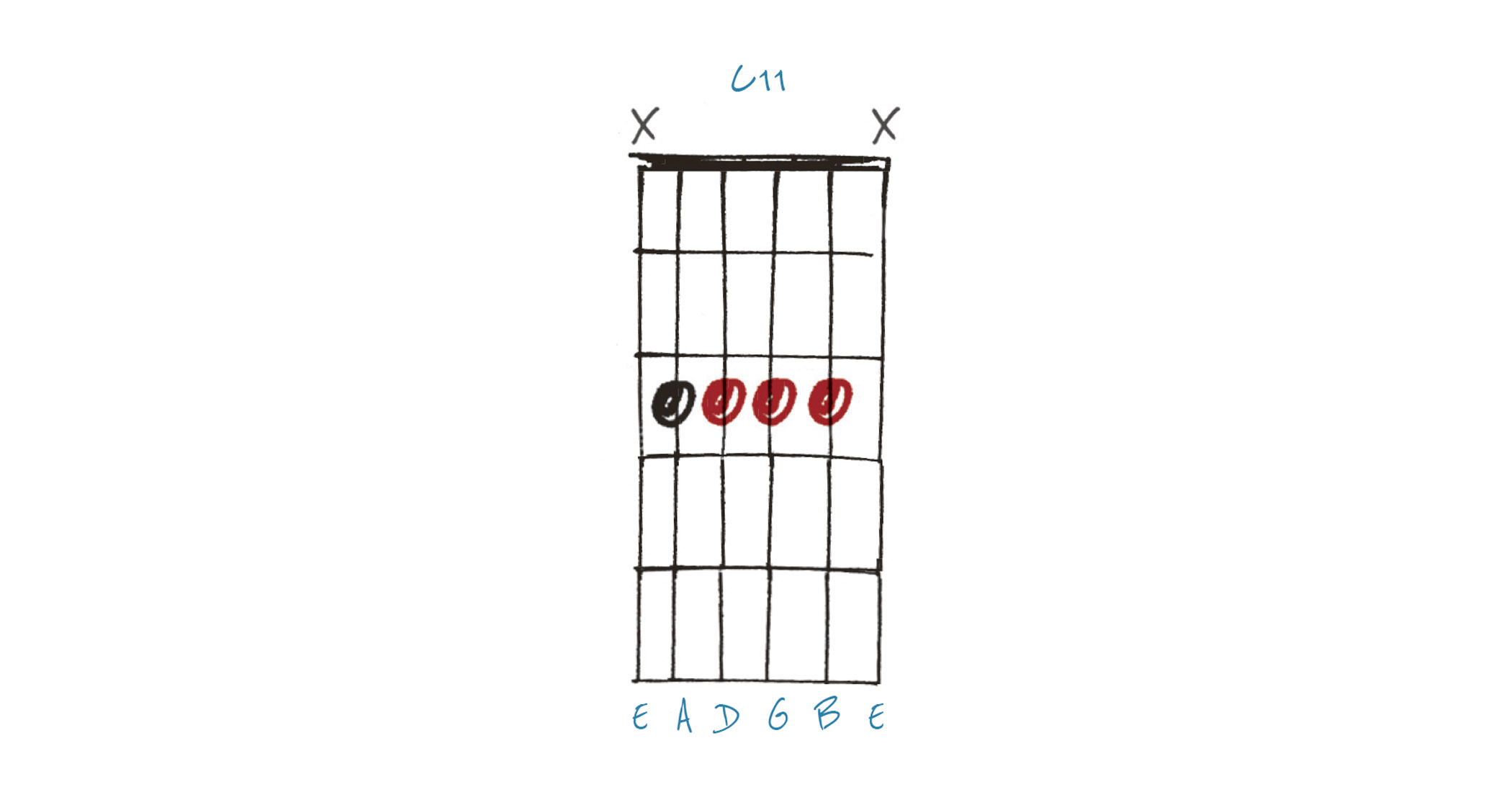

Example 2

This C11 is a good example of stripping an extended chord down to the essentials, partly due to necessity and partly for clarity. Instead of the six-note ‘stack’ of Root-3rd-5th-b7th-9th-11th (C-E-G-Bb-D-F), we consolidate to Root-11th-b7th-9th (C-F-Bb-D) in ascending order. The 3rd (E) is omitted, as is the 5th (G), but this could be added on the first string if desired, aka Bb/C.

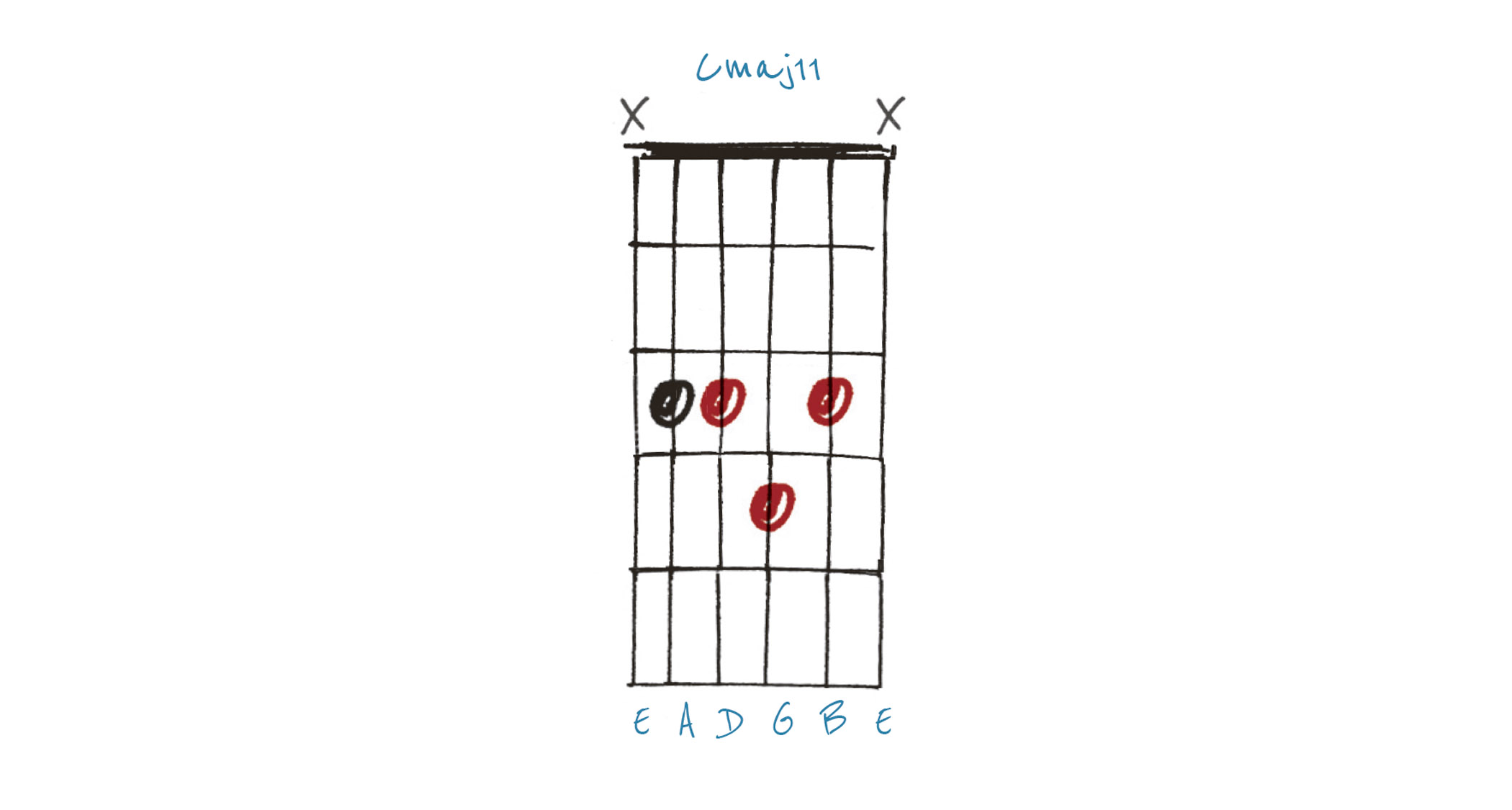

Example 3

So far we’ve been building 11th chords using the dominant or b7th, but we can also do this with a major 7th. In this case, the C11 from Example 2 is changed to a Cmaj11 by raising the b7th (Bb) to a B natural. This major 7th is what gives the ‘maj’ part of the chord its name.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

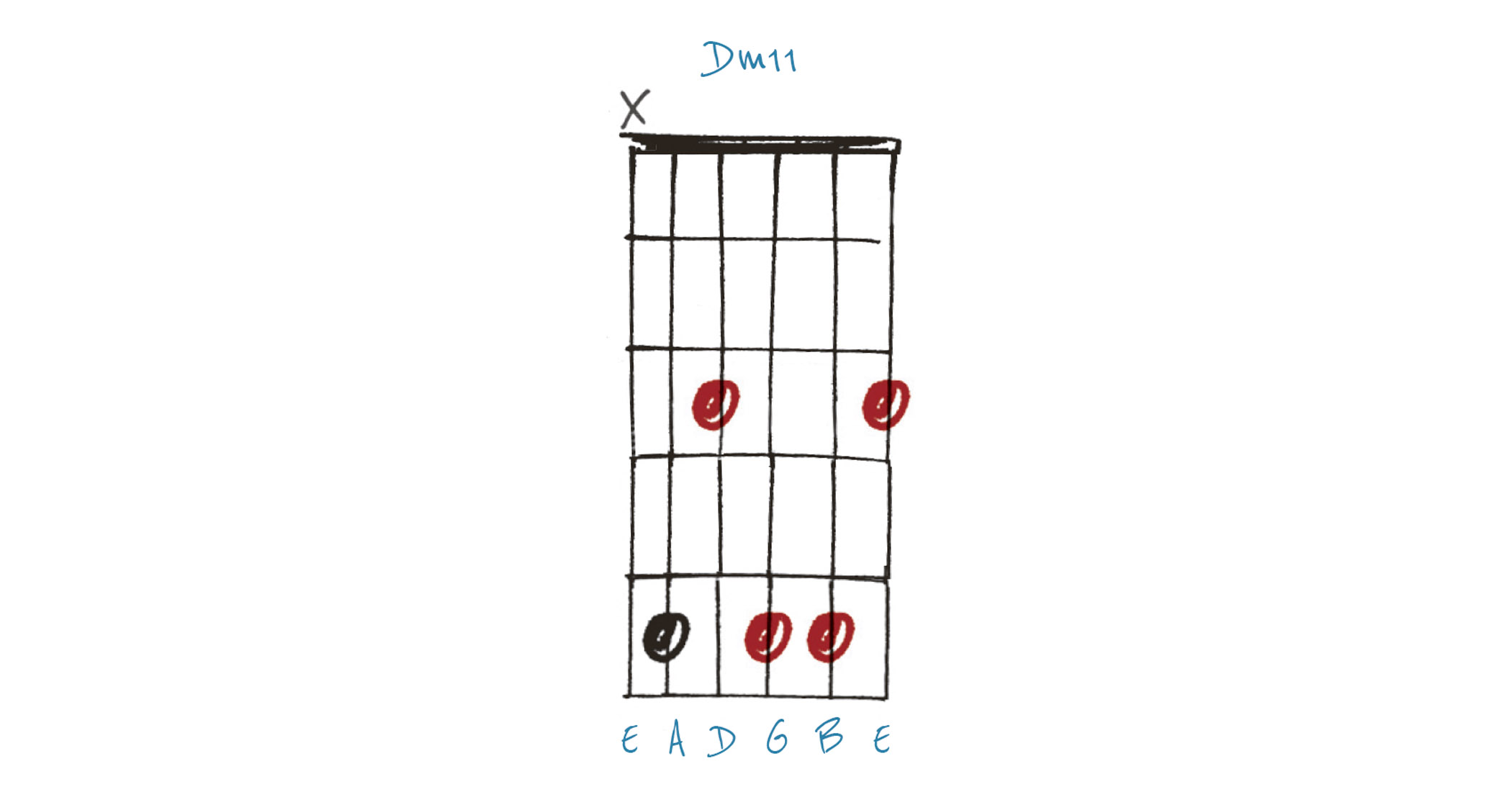

Example 4

We can build an 11th chord from a minor triad, too, as this Dm11 demonstrates. In theory, a min11 chord is built from Root-b3rd-5th-b7th-9th-11th (D-F-A-C-E-G) in this key. Looking at the chord diagram, we do actually have everything apart from the 5th (A) – and in scale order to boot!

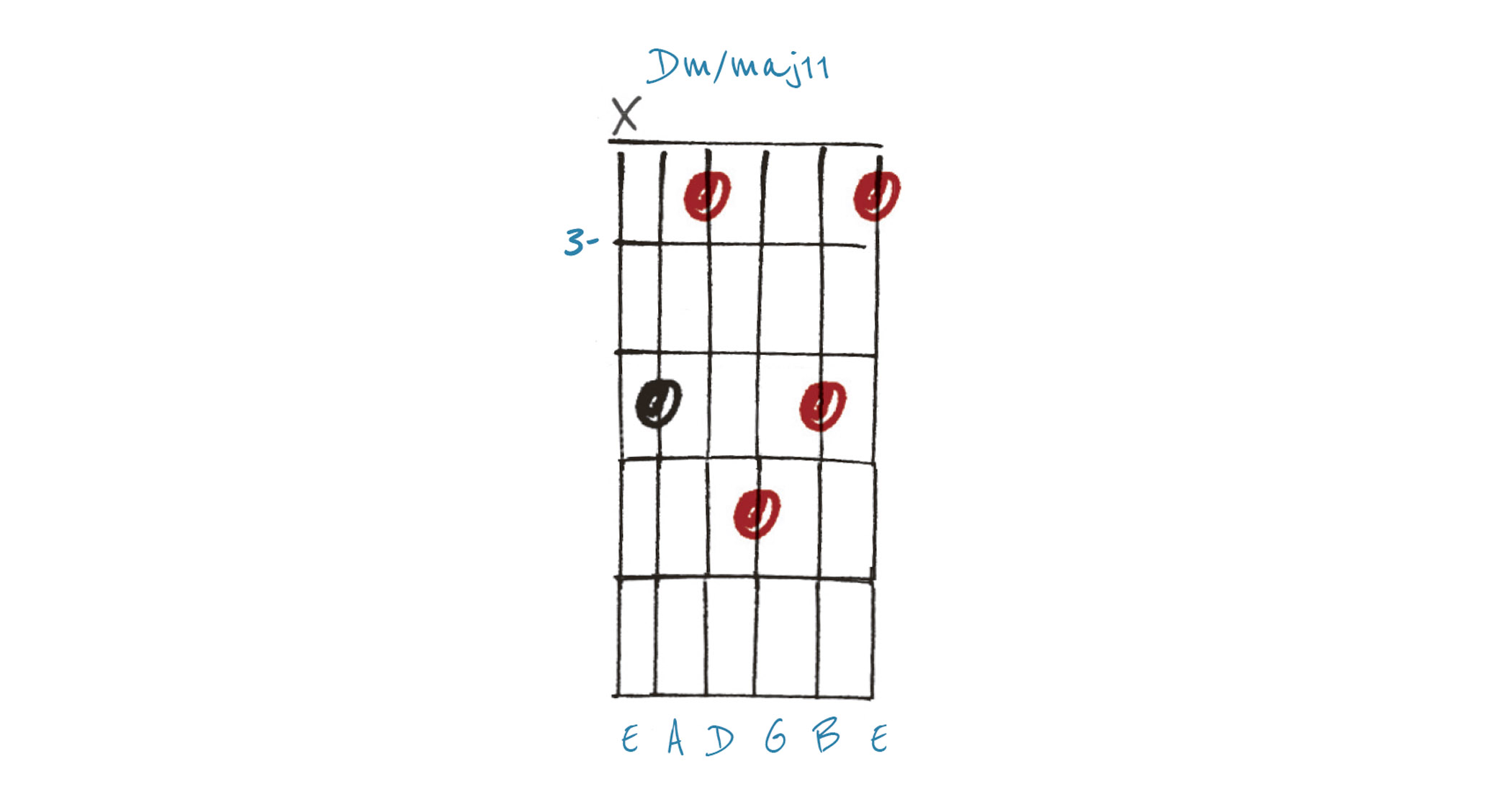

Example 5

In Example 3, we built a maj11 chord starting with a major triad. If we raise the b7th in our Dm11 from Example 4, we get this somewhat dramatic-sounding Dm/maj11. It’s a little bit of a twist for the fingers as well as the brain, but hopefully it demonstrates the thinking behind some of those mysterious chord-naming conventions!

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.