“Playing with Vince Neil, opening for Van Halen, it got to be total rock ’n’ roll excess. I had to reassess why I was even playing guitar”: Steve Stevens on resisting shred, how Paco de Lucia made him go nylon, and Billy Idol’s eternal appeal

Billy Idol’s collaborator of 40-plus years transcends the punk-rock guitarist mold, taking in flamenco, jazz‑fusion, prog and classical styles – and he is as excited about guitar today as he was when he first picked one up

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Whether igniting Billy Idol’s biggest anthems or unleashing fiery flamenco on his own, Steve Stevens has never played it safe and never stood still.

More than 40 years into his career, he remains sharp as ever. As Idol’s long-time right-hand man and collaborator, Stevens helped define the sound of the ’80s but refuses to be just a relic of that era.

With a recent Billy Idol album, an ambitious tour and new signature gear, he continues to set stages ablaze with the same passion and precision that made him a guitar hero. Here, Stevens joins us to reveal how he’s been able to stay relevant in an ever-changing musical landscape.

The latest Billy Idol album, Dream Into It, dropped earlier this year. Has your songwriting process evolved over the years?

As far as Billy and I go, nothing’s really changed: it’s still two guys in a room with acoustic guitars. We’ve always felt that if a song works acoustically, you’ve got something. If it only works once you layer technology on top, maybe it’s not strong enough. That’s always been our litmus test.

But we also had other collaborators this time like our producer Tommy English, plus Joe Janiak, who we’ve worked with before, and Nick Long, who we had worked with a little bit in the past.

These guys are younger, but they grew up with Billy Idol’s catalogue. They’re excited about the legacy and they know how to bring in elements from the past without just recycling it. That kept things fresh.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What unexpected influences found their way onto the record?

One of the bands that influenced me and Billy early on was Suicide, the New York duo of Alan Vega and Marty Rev. When Billy first moved to New York, we must have seen them three or four times. They had this primitive, lo-fi electronic thing going.

So when we used synths or drum machines on this album, we wanted them to feel stripped-down, raw and almost primitive. These days, plugins can sound massive, so we went the opposite direction and kept it small. Those raw textures worked really well with my guitars.

Lyrically, Billy wanted the songs to reflect his life story. We knew he had a biopic film coming out this year [Billy Idol Should Be Dead], so it made sense to tie the record to his journey. Even though I wasn’t with him back in England where he started, I’ve certainly been there since he arrived in New York. Here we are 42 years later, still working together, so there’s a lot of shared life experiences to draw on.

How did you approach your guitar tones for this record?

I’m old-school, so I like to just plug straight into an amp. I’ve got my Friedman Steve Stevens signature head and my Knaggs guitars. Where I did experiment was in creating soundscapes. Since we didn’t want keyboards dominating the record, I used plug-ins and effects to get textures with the guitar.

That was kind of the concept even back on Rebel Yell. We started recording it back in ’83 when all these records were out with tons of keyboards and we didn’t want to sound like everyone else. I remember telling our producer, Keith Forsey, ‘Let me try it on guitar first. If it doesn’t work, then we’ll add keys.’ And most of the time, guitars carried the weight.

Live, how do you approach material from albums such as Charmed Life and Cyberpunk that you didn’t play on originally?

Funny enough, I’m usually the one saying I want to do tunes off those albums because I love interpreting them; it’s almost like doing a cover song. I mean, I’m a Billy Idol fan as well as his guitar player.

I remember when we did Prodigal Blues from Charmed Life, we played an acoustic version and I approached it almost like a Ry Cooder tune.

Billy said, ‘Wow, where did you get that idea?’ and I just told him, ‘I listened to the song and that’s the way I heard it.’ We do that a lot. I get to reinterpret the songs, sometimes even using a guitar synth, and it’s such a great challenge.

Tell us about your new Ciari Steve Stevens Signature travel guitar.

I came across a video of this folding guitar that fit into a backpack. I understand mechanical design a little bit so I thought, ‘Wow, this looks cool.’ As a touring musician, I always have my laptop and a guitar with me for writing, laying down tracks and even recording stuff for other artists, but I’ve always been nervous about travelling with a guitar and checking it at the airport as baggage. The Ciari guitar looked like a great solution.

I contacted [Ciari Guitars founder] Jonathan Spangler whose background was in [medical device technology], and I thought, ‘How do you go from that to designing guitars?’ [Laughs] But the mechanics were incredible.

I started travelling with one, and eventually Jonathan asked if I’d be interested in doing a signature model. We put in custom Bare Knuckle [Ray Gun] pickups made exclusively for this guitar along with an ebony fingerboard, coil-taps and even a tuner built into the pickup ring. It’s invaluable on the road and I use it on stage for our encore every night.

You’ve been in the spotlight for decades now. What’s been the key to staying relevant without chasing trends?

I think it’s always been cool to like Billy Idol, and our records were never something you could pigeonhole. I came from the rock side with guitar heroes like Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, a little prog, some new wave and New York punk.

Then you have Billy with the punk-rock/Elvis thing, and our early producer Keith Forsey came from working with [Italian composer] Giorgio Moroder on dance records like Donna Summer. So, because we’ve always had this gumbo of different styles, we were never pigeonholed when it came to writing music.

Even though we had our biggest success in the ’80s, Billy’s roots go back to 1977 London. I think that’s served us really well. He’s got a timeless image and people appreciate that. He’s a real-deal rock ’n’ roll star. Honestly, we sound better now than we did back then.

You’ve worked on many side projects over the years.

I was fortunate in the ’80s because, as a sideman, people approached me probably more than if I’d been tied to a band. I got offers from Robert Palmer, Joni Mitchell, Michael Jackson and, of course, Top Gun. I was able to do all those one-offs while still working with Billy.

I think it’s always been cool to like Billy Idol, and our records were never something you could pigeonhole

I like working with artists outside my comfort zone. For example, I worked with Ben Watkins [of Juno Reactor] on soundtracks like Once Upon A Time In Mexico and The Matrix. I love his records and wanted to understand how they were made, like sampling, loops and all that early ’90s electronic stuff. I like working with flamenco players and world artists, too.

The worst thing would be if someone asks me to do something for them that sounds like Rebel Yell. That’s exclusive to Billy Idol and I don’t want to retread; I turn down those requests.

Speaking of flamenco, didn’t you do a flamenco record at one point?

Yes, it’s called Flamenco A Go-Go, released in 1999. After a run playing with Vince Neil, opening for Van Halen for about six weeks, it just got to be total rock ’n’ roll excess [laughs]. I came off the road and had to reassess why I was even playing guitar.

One of my first loves is flamenco and my first guitar teacher was a flamenco guitarist. I remember going to see Paco de Lucía and that reignited this spark in me. I stopped playing electric guitar for a year. I went to Japan, France and England to make that record and travelled the world with just my nylon-string guitar.

When you’re playing genres other than rock, do you feel more creatively challenged?

Absolutely. One of the unique things about my style is how I was influenced by early synthesizers and keyboards like Keith Emerson with The Nice, Rick Wakeman, all that stuff. A lot of my guitar ideas come from keyboard sounds from the ’70s.

Same with flamenco rhythms applied to my acoustic work. I also listen to a lot of film scores and classical music.

Their arrangements are incredible. For me, being a successful guitarist is about coming up with parts that move the song along and not just doubling the bassline. I always want a guitar part that’s independent.

Are you consciously thinking ‘keyboards’ when you’re playing or does it just happen naturally?

Definitely consciously. Take the middle of Rebel Yell, during the ‘I walk the world’ section. That guitar line is me thinking of Emerson’s Lucky Man solo [Emerson, Lake & Palmer]. I’m not thinking guitar. Same with orchestral-style chord voicings.

On Flesh for Fantasy, for example, those chords are influenced by Allan Holdsworth but also by Rick Wakeman’s use of 9ths and 7ths. I never just play straight major or minor. There’s always something extra.

You’ve worked with many different artists over the years. Who else is on your bucket list?

Peter Gabriel. I love everything he’s done and I think he would be incredible to collaborate with. I enjoy working with artists that have influenced me. I got to share a stage with Neil Young once. When I got my first decent acoustic guitar, I played a lot of his stuff so it was amazing to play on stage with him.

What’s important, especially after decades, is not forgetting that feeling you had when you first picked up the instrument. You can’t let mortgages or taxes creep into your head. You’ve got to stay excited.

Thinking back to the ’80s, there was a lot of pressure to be able to shred, but you didn’t really fall into that.

I wasn’t from LA. I didn’t grow up watching Van Halen thinking, ‘Oh shit, what do we do now?’

I wasn’t from LA. I didn’t grow up watching Van Halen thinking, ‘Oh shit, what do we do now?’ A lot of guys did. Eddie shook up the world, no doubt. I became friends with him later, but I never wanted to play like him. Record labels were signing anyone who could tap and shred. The good ones, like Warren DeMartini and George Lynch, found their own voices, unlike guys that were just Eddie clones.

But, really, my true love is collaborating on a good song. I’m definitely not looking for my moment of glory three minutes into a song, waiting for the guitar solo. I enjoy being part of the band more than anything and having that dialogue with the guys on stage, playing and locking in with the drummer.

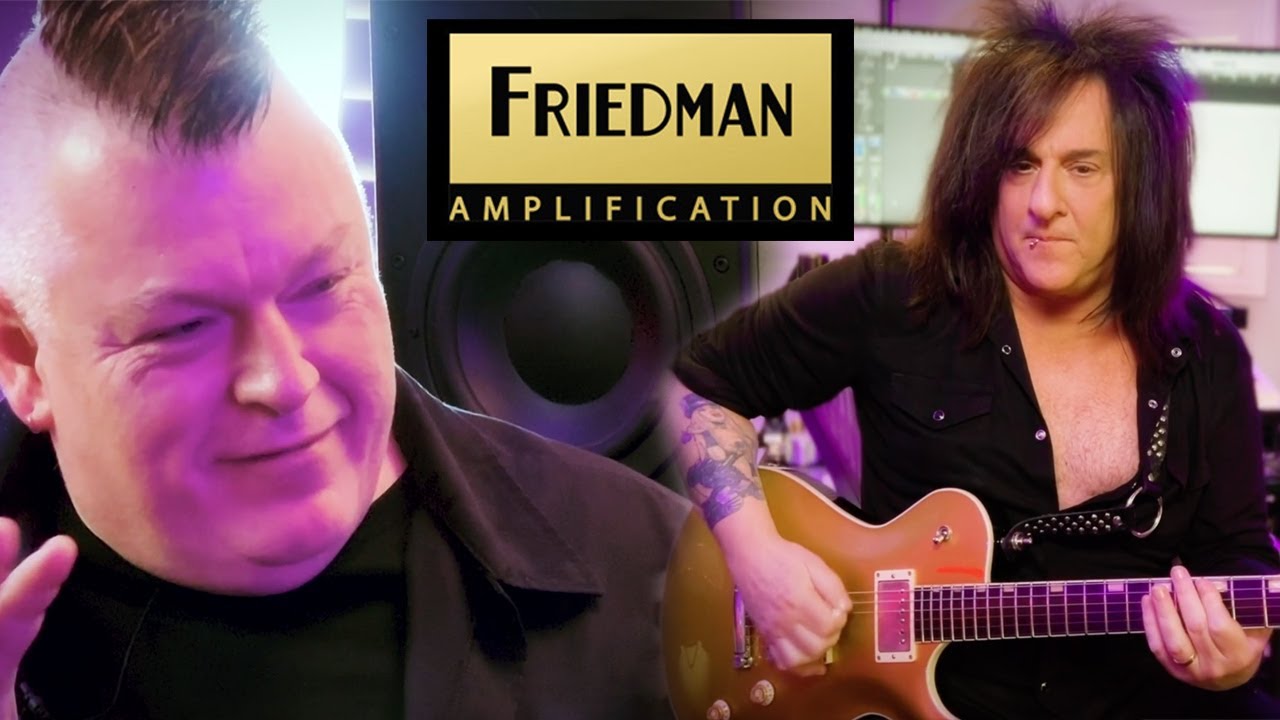

Dave Friedman claims you were very hands-on when it came to designing the Steve Stevens signature tube amp.

[Laughs] Yeah, Dave and I go way back, before he was even building amps. I’d moved to LA and my live rig was in bad shape so he rebuilt it for me. It started as a good Marshall ‘Plexi’-inspired amp with a great master volume. Then we expanded by adding a clean channel and we just kept refining it from there.

To my ears, I’m just replicating my favourite early ’70s records, especially the English ones and the glam stuff like T. Rex, Bowie, Sweet. Those records always had amazing guitar sounds. Those are the guitar sounds that I like to hear.

Tell us about your touring rig.

Dave Friedman built my rig for this tour, [it’s] all pedals now. I use a Fractal FM3 for delays, chorus and harmonies, a custom wah from Oxbow Studios that nails the Hendrix-era Vox sound, and I’ve also got the Rockaway pedal that I designed with J Rockett, which is like a Klon but with a graphic EQ.

Also there’s a couple of Ernie Ball volume pedals, a ring mod sequencer… I change things a lot. That’s the fun part about using pedals. It’s easy to switch stuff in and out.

With IRs and a great front-of-house guy, my live tone is more consistent record-quality

We’re using in-ears, so no cabs on stage. I worked closely with several companies to develop my own IRs [impulse responses]. I went to front-of-house and compared my mic’d cabs to the IRs, and the IRs sounded better. A lot of players fool themselves with their stage sound and don’t realise that the audience is not hearing what they’re hearing.

With IRs and a great front-of-house guy, my live tone is more consistent record-quality. I used to hate in-ears, but I’ve learned how to make them work using specific reverbs, house mics blended into the mix and other little tricks. Now I can hear everything clearly without blasting my ears.

Don’t you miss that wall of sound behind you?

I’m 66 years old – I’m too old for that now [laughs].

- Dream Into It is out now via Dark Horse.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

Charlie Wilkins, known as “Amp Dude,” is a seasoned guitarist and music journalist with a lifelong passion for gear and especially amplifiers. He has a degree in Audio Engineering and blends technical expertise with a player’s insight to deliver engaging coverage of the guitar world. A regular contributor to top publications, Charlie has interviewed icons like Steve Stevens, Jared James Nichols, and Alex Lifeson, as well as guitar and amp builders shaping the future of tone. Charlie has played everything from thrash metal to indie rock and blues to R&B, but gravitates toward anything soulful, always chasing the sounds that move people.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.