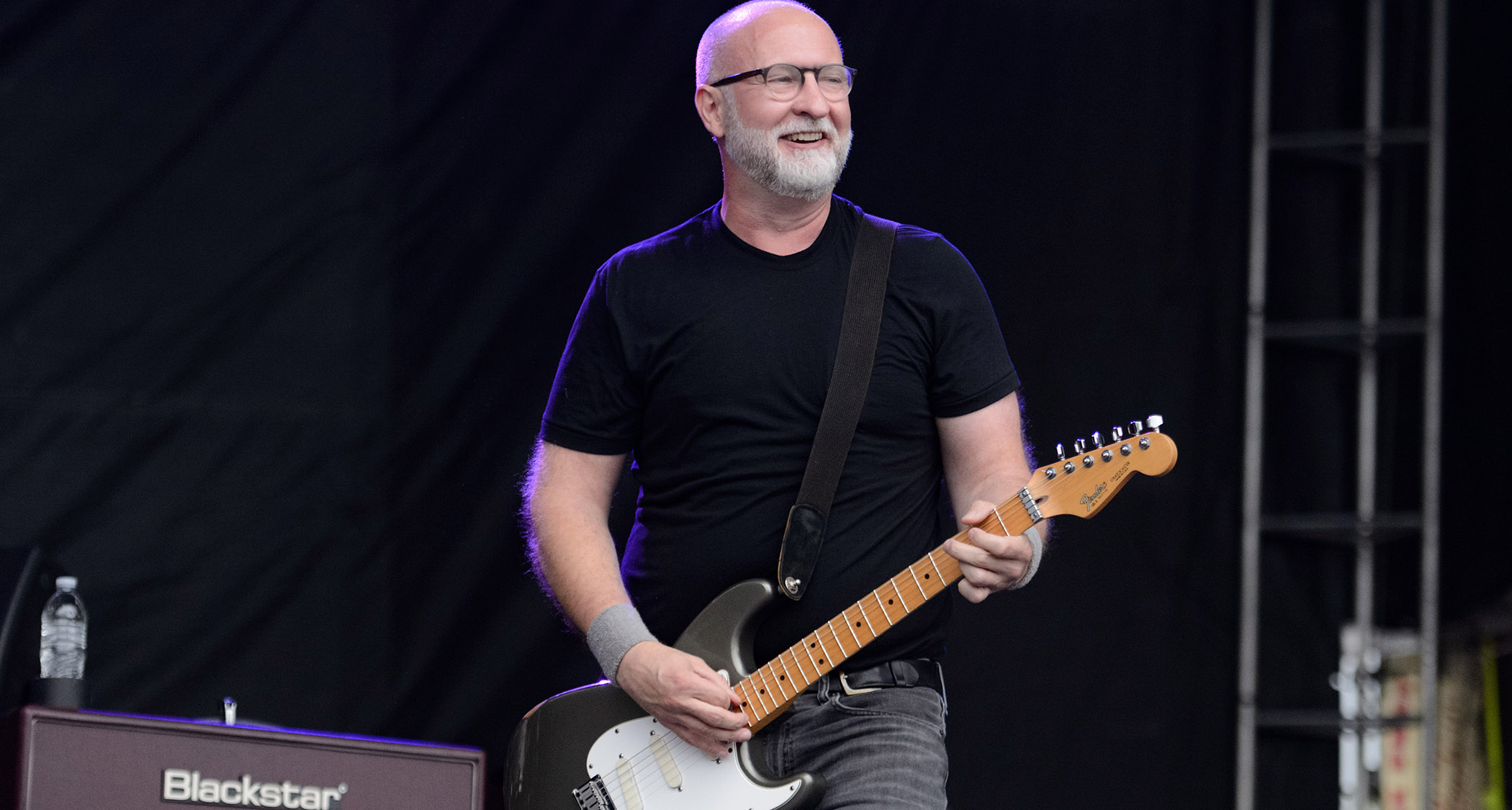

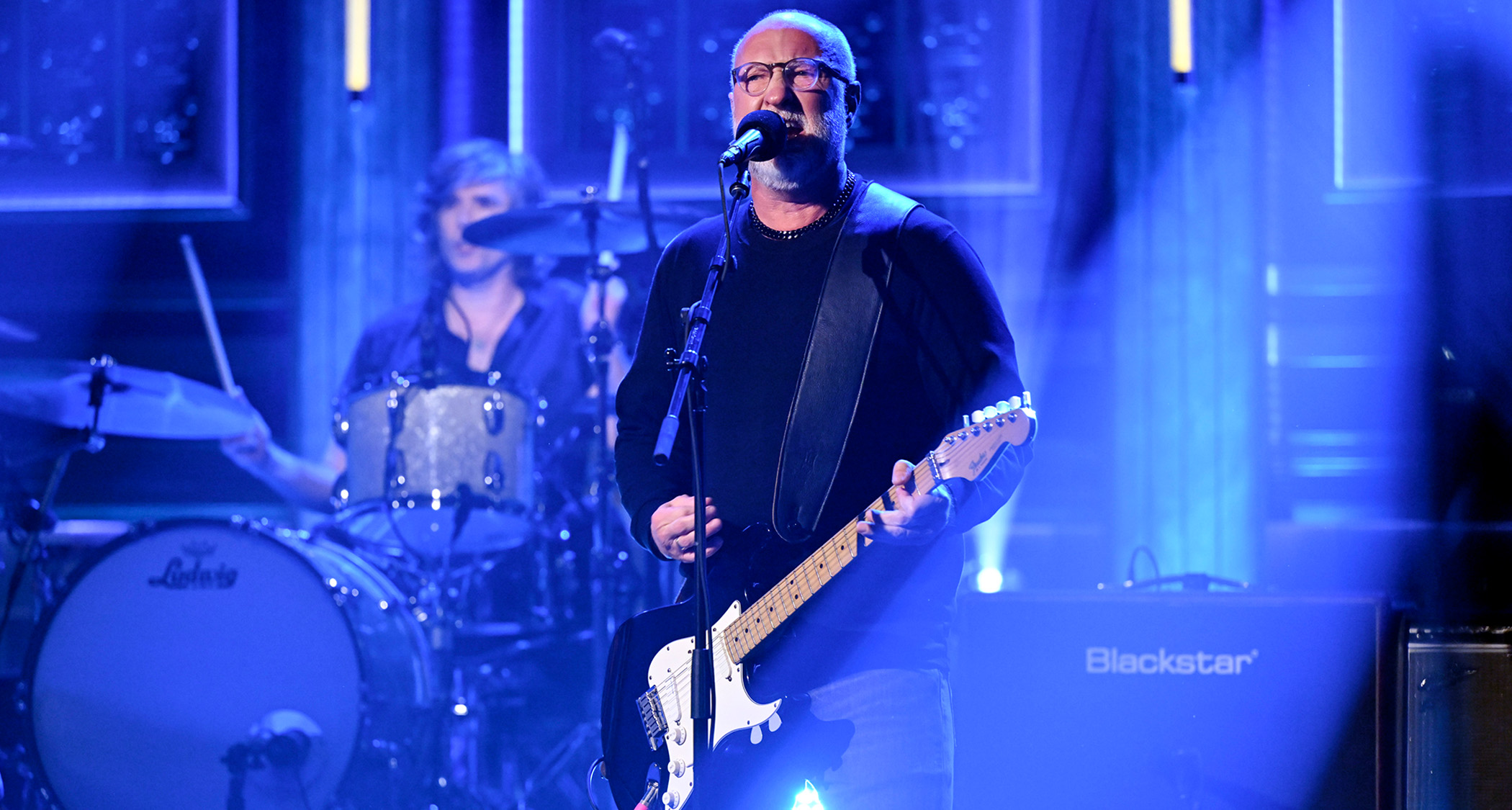

“We went to Waffle House and I saw a sugar packet. Those songs went from being the third Bob Mould solo album to being by a band called Sugar”: Bob Mould on Hüsker Dü's rise and fall, and what changed when he swapped his Ibanez Rocket Roll for a Strat

In a rare interview, the Hüsker Dü and Sugar mastermind walks us through his entire career, right on up to his brand-new “give the people what they want” record, Here We Go Crazy

Prolific songwriter Bob Mould is a reluctant generational icon. Sure, he’s proud of his musical accomplishments and realizes he has been a major inspiration for a wide range of mainstream acts, including Nirvana, Pixies, Weezer, and Green Day.

He’s well aware that if it weren’t for the open chords and ringing hooks he injected into Minnesota-based Eighties hardcore band Hüsker Dü and later, Sugar, college music and alternative rock might not have evolved in quite the same way. And yet, like some of the groups he has inspired, he doesn’t relish being in the spotlight and cherishes his privacy.

“I would not like to think I’ve been difficult. I prefer to think of it as challenging,” Mould says, relaxing at his home in Palm Springs, where he moved in 2020 after a stretch in Berlin.

“I know I might sometimes come across as pretty contrary and enigmatic, and maybe that comes from always getting asked what I’m trying to do with something, when half the time I might not really know. If it wasn’t for people asking, I wouldn’t even think about it. I’d just be on to the next project.”

Mould feels most at home when he’s writing and performing. He’d rather vent his sentiments through swarming, honey-rusted guitar lines and finely crafted rhythms than conversational banter. He has never bought into hype or catered to expectations, which is likely why he hasn’t risen to the commercial heights of many of the musicians he has inspired.

And he’s okay with that. Mould values authenticity more than celebrity, and not having to worry about whether his handlers and record company will consider his music mass-marketable has allowed him to remain fiercely independent.

As highly regarded as the eight studio recordings (and two EPs) Mould made with Hüsker Dü and Sugar are, they only account for about half of his career recordings. And while Mould’s 15 solo albums often feature his trademark guitar sound, they cover a far broader range of styles than punk and alt-rock, including pastoral, folk-inspired music, tarpit-clotted hard rock, jangly singer/songwriter fare, fizzy pop, orchestra-embellished rock, and even beat-thumping electronica.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Some musicians take a long time to find their true voice. Others find it relatively early – like Bob,” says author and journalist Michael Azerrad, who co-wrote Mould’s autobiography, See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody. “But they become restless, because they're – you know – artists, and they want to try new things. Maybe it works out, maybe it doesn't, but the point is to try, which can be very risky artistically and commercially. Bob deserves a lot of respect for all the chances he's taken over the past 46 years.”

I know a lot of people sit down with an objective when they work. I don’t like to do that. With any writing process, at the beginning of a cycle you have no idea what you're doing

With the exception of albums from his dance music period, Mould has never started working on a record with a specific goal. He has just picked up a guitar – usually his blue 1988 Fender American Standard Stratocaster or a Yamaha APX 12-string – and spontaneously assembled chords and notes, allowing his experiences and environment to guide his creative flow.

“I know a lot of people sit down with an objective when they work,” he says. “I don’t like to do that. With any writing process, at the beginning of a cycle you have no idea what you're doing. You try to be unconscious. You try to get a couple ideas down and move on from there. It’s like getting a stake, some poles and fabric, and once you’ve identified those, you have something you can stretch your fabric across to make a tent.

“And then you start filling in the color of the fabric and decide on the height and size of the tent. You identify the things that are good about what you’ve built, and you put together everything else around it in a way that makes sense.”

Some fans of Hüsker Dü and Sugar have been disappointed by Mould’s solo albums, which have been driven by a determination to experiment with different sounds and styles. However, on his first release in four years, Here We Go Crazy, Mould has returned to a framework of driving riffs, propulsive melodies, and confessional lyrics that sound instantly familiar and welcoming, and he performs with a reverence for the past that fans of his most popular releases have applauded.

“A lot of the sound of this album comes from doing solo shows for two and a half years,” Mould says. “I got to reconnect with the audience and really understand what they like about my work. I used that as a guide of sorts for the new songs.”

On a foggy late-winter afternoon, we took a winding stroll with Mould through some of his most revered albums and discussed the circumstances that led him from being a rebellious punk kid to an alt-rock pioneer.

We also addressed his life as a guitar player, from the first time he picked up the instrument to the gear he has used to create his trademark tones. And we discussed his unquenchable desire to always grow as an artist and reflect his life through his music.

When did you start writing music?

“I taught myself music theory as a child and wrote simple keyboard parts. I performed them at a talent show in grade school. I didn’t pick up a guitar until I was 14 and I played with some friends, but that was it until we formed Hüsker Dü [Mould, drummer Grant Hart, and bassist Greg Norton].”

What drew you to the guitar?

“I thought, ‘I like rock ’n’ roll. I like Cheap Trick. I like Kiss and Aerosmith. Maybe I should pick up a guitar and do something?’ I got a Sears Strat copy – the functional $90 guitar – and a cheap amp, and I taught myself to play. I had exactly two guitar lessons in my life, so I didn’t have a lot of help or guidance.”

Did not knowing the conventional approach to playing give you more room to explore and discover?

“It was great to figure out stuff on my own. I thought, ‘Look at how much I can do with all these open chords.’ Then you find out about capos and it’s like, ‘Wow, you can do the same thing in all keys!’”

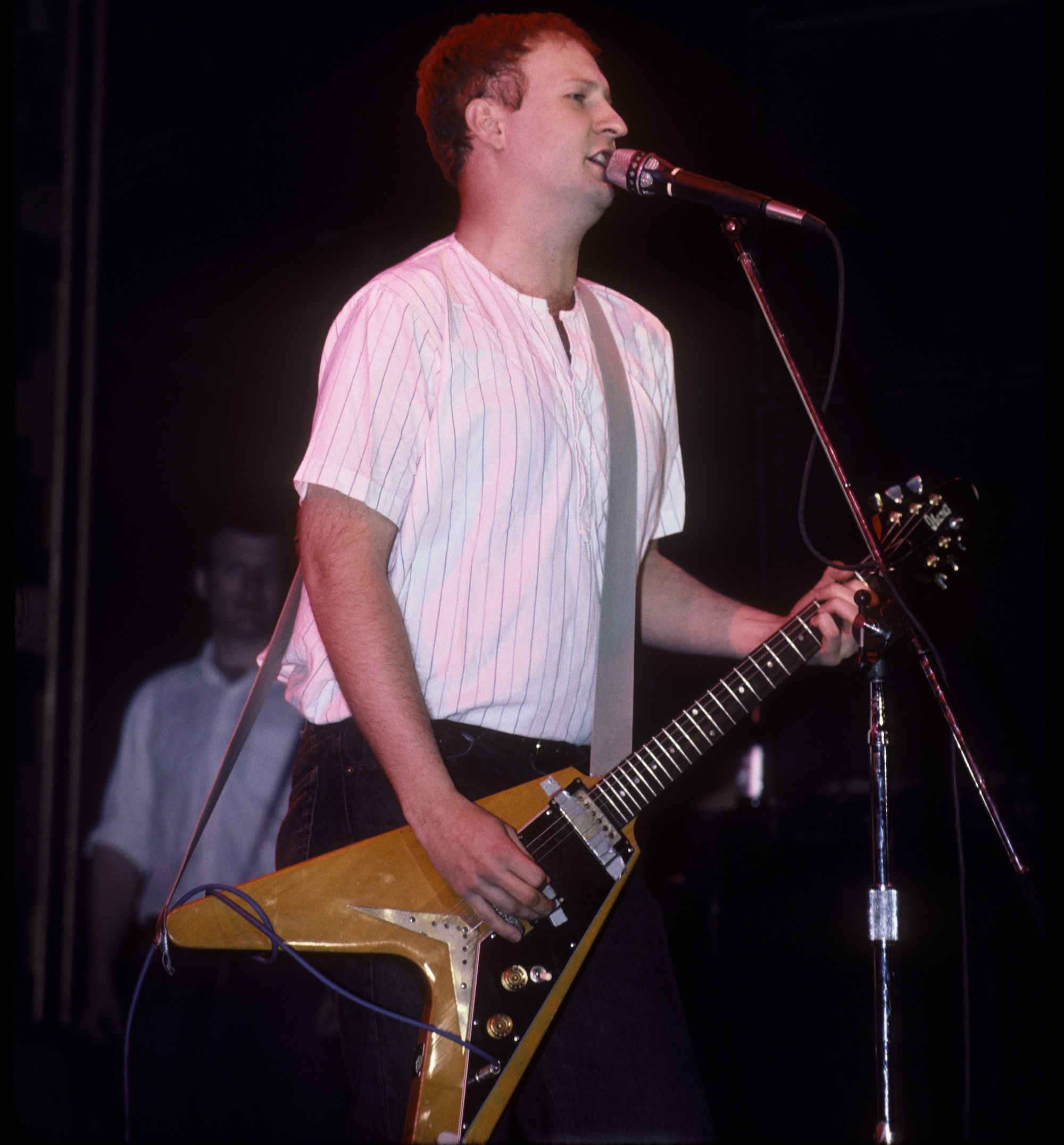

In Hüsker Dü, you played an Ibanez Rocket Roll, which looks a lot like a Gibson Flying V. How did that contribute to your tone?

“I picked that up right before I moved from the Adirondacks [in upstate New York] over to the Twin Cities [Minneapolis–Saint Paul in Minnesota]. We were a trio, and I wanted the guitar to be loud and fill up a lot of space. I plugged the Flying V into a Seventies Electro-Harmonix Mike Matthews Dirt Road Special, and that was the core sound for a while.”

You played typical punk chords, but you also used open chords with buzzing distortion, which gave your angry, biting riffs a sweet melodicism.

“Yeah, that’s the sound, and I’ve refined it over the years. I used an MXR Distortion Plus and later some chorus, which might have contributed to that tone. My original style, to me, felt like an amalgamation of Pete Townshend, Johnny Ramone, and Johnny Thunders.”

How so?

“Pete Townshend was the sole guitarist for the Who, so he had to play rhythm and lead at the same time. I did the same kind of thing in Hüsker Dü. As for Johnny Ramone, the Ramones changed my life. Their energy and speed influenced me as well as their great riffs. They played barre chords all the time, and that was the era of the single note solos.

...the Ramones changed my life. Their energy and speed influenced me as well as their great riffs

“Then there was Johnny Thunders from New York Dolls and also the Heartbreakers, where he had that Chuck Berry approach with all the surf dive bombs. There were other players I liked, but those were the main three.”

Hüsker Dü’s first full-length release was 1982’s Land Speed Record, a crazy-fast live hardcore album. By the end of 1983, you released the frantic noise-fest Everything Falls Apart.

“We went through a couple of iterations, including a brisk, poppy period and a time doing dark, chimey stuff like Joy Division. A couple years into just making it up, we tapped into a much more hardcore sound.

“In around 1981, Hüsker Dü were booking shows on the fly and playing with bands like DOA, Poison Idea, the Dead Kennedys, and MDC. Seeing that other people were doing that hardcore thing, I think it’s fair to say we got more competitive and tried to play faster.”

Did the speed of the music stem more from rage or joy?

“That’s a great question. I don’t know if I've got a definitive answer. It was exciting to be part of something, but, at least for me, the aggression came from somewhere real. As a then-closeted young gay man in [Ronald] Reagan’s America, I was pretty angry at the state of the world.

“Anti-gay sentiment was building, and then HIV showed up and a pretty awful stretch of time followed. I think all of that fueled a fair amount of the work I was doing, and to me, that would be the only good thing that came from the Reagan administration.”

Did you find acceptance in hardcore?

“I look back at the hardcore scene as a land of misfit toys. It was a lot of people who didn’t belong anywhere else, and getting into that community was the ultimate goal for me. We created alternative spaces through independent radio, fanzines, and sharing information. I didn’t embrace it as a tool for anarchy. There was an element of protest there, but I always thought of it as protest for change.”

Hüsker Dü’s second studio full-length, Zen Arcade, was a double-album, which was an anomaly for hardcore. It was far more tuneful than Everything Falls Apart but still fierce.

“That was the moment when everything changed. We were driving down the West Coast from Seattle to Los Angeles when I came up with the rough framework for a concept album. We wanted to break out of the confines of what we saw around us in hardcore. We wanted to do something expansive, so we dialed down the simplistic politics and turned up the autobiographical emotion.

“A lot of it was based on my life. It’s about a kid growing up in a violent, broken home. So he goes to California to design video games and finds himself in a game called Search. That was the rough outline, and it came together quickly.”

The public response to Zen Arcade was tremendous, largely because music that fierce and fast was rarely filled with hooks. Did you feel affirmation from the press that you were doing something groundbreaking?

“No. We had not yet gotten the blessings of the critics because Zen Arcade was barely out by the time we were touring for the next album. Let me lay out the calendar so it makes sense: In October ’83 we recorded Zen Arcade. It’s scheduled to come out in June or July of ’84, but SST can’t press enough records so the release gets delayed.

“The band is on tour in the summer of ’84 playing a record that’s still not out. In September ’84, Zen Arcade finally comes out, and by then, we had already recorded our next album, New Day Rising, and were writing Flip Your Wig. That delay created this crazy bottleneck of music.”

Did that cause friction between the band and the label?

“We were frustrated with them for being late getting Zen Arcade out. So, as we went along we made sure we took back the reins of our career from anyone else who was holding them and we kept moving forward.”

Some have called New Day Rising the album that bridged the gap between hardcore and alternative music.

“To me, it was just a continuation of the work we were doing. I think of Zen Arcade, New Day Rising, and Flip Your Wig as a series, and New Day Rising is the transitional record of the three.”

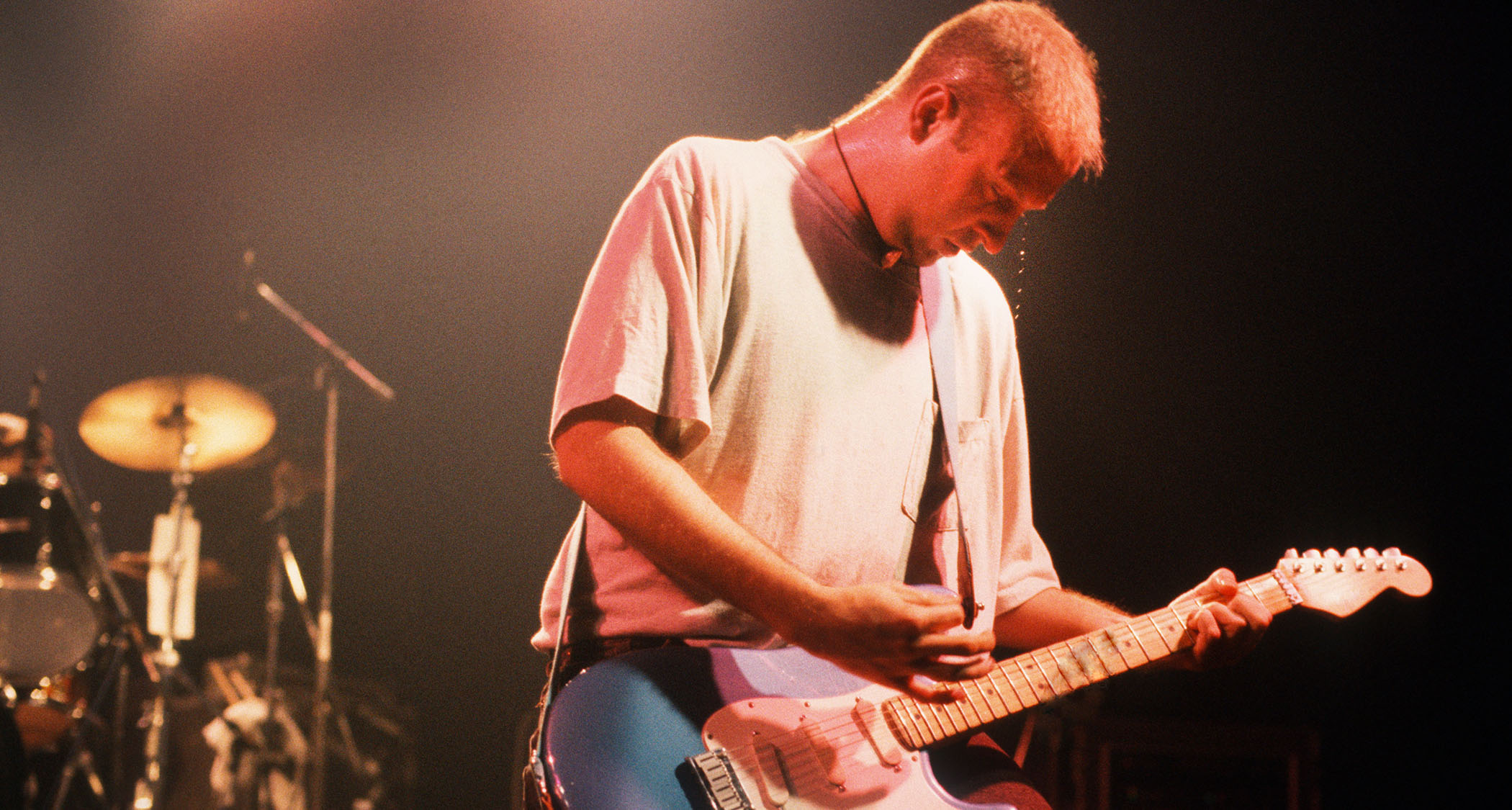

Flip Your Wig features some of Hüsker Dü’s most melodic tunes, including Makes No Sense at All. Did you want to make a more commercial record, and did you use different gear to get a more mellifluous guitar tone?

“I got a Fender Silverface Deluxe, but I was still using the [Ibanez Rocket Roll] with the chorus. It was a great time, the best. It was me and Grant making a pop record our way without anybody looking over our shoulders. Hence the title. Flip Your Wig was the name of the Beatles board game [from 1964].”

Were you always a pop music fan?

“I was born in 1960, so I grew up with pop music in my DNA. When I was a kid, jukebox singles were my toys, so Flip Your Wig was fun and easy to make, and it’s my favorite Hüsker Dü record. At the time, we were on fire. There was nothing that could stop the band except ourselves, and, over time, that’s what happened. But back then, we were on a tear. I didn’t think anybody could touch us.”

You ripped from one album to the next, with an abundance of songs to spare.

“We were going nonstop. We were like three fighter jets all trying to be in the lead. When I listen to the records, the foundation of everything is shaky, and that’s not to badmouth it at all. That’s just the way we sounded. Everybody was racing, full speed, full energy all the time. There was constant forward momentum, especially live. If I go back and listen to shows from that era, it's off the hook.”

We had a terrible run of shows in December of ’87 that led to a situation where Greg and I wanted Grant to clean up his problems and try to get back to work. That plea did not work. The problems didn’t get fixed, so I quit – and that was the end

You’ve been open about how alcohol fueled the band’s abundant energy.

“For me, it was functional alcoholism, for better or worse. I was moving through the day and nothing was gonna stop me. I was drinking a fair amount. Greg probably was drinking. Grant was drinking. I wasn’t keeping track of how much, but all the work would get done. The shows happened and they were great.

“When we needed to deal with record companies, we were perfectly fine. There was a lot of alcohol but we were constantly moving forward, which is a weird thing. I wouldn’t advise that if I were a career counselor: ‘Just drink all the time and keep moving ahead really fast. You’ll do great.’”

Hüsker Dü signed to Warner Bros. and rapidly recorded its two most melodic rock records, including the double-album Warehouse: Songs and Stories. That’s 30 new songs in 10 months, plus touring. Did the band burn out by going too fast for too long without a break?

“There were other factors. In the summer of ’86, I stopped drinking. That was the beginning of the last 18 months of the band. Greg and Grant had idiosyncratic behaviors of their own that also contributed, but I only feel comfortable speaking about myself. When I quit drinking, I changed as a person.

“It cost me a lot of acquaintances because so much of what I did with my days and nights had revolved around bars and drinking. And it changed the dynamic of the band.

“Greg moved an hour away and started spending time on other interests, and Grant drifted away from us and toward a different group of people I didn't know. I could sense things were changing, but it was nothing I could put my finger on until the very end of the band.”

Were you growing apart musically?

“I had let a lot of songs go and I wasn’t happy about that. Grant let some songs go, too. That was restrictive for both of us.”

What was the straw that broke Hüsker Dü’s back?

“We had a terrible run of shows in December of ’87 that led to a situation where Greg and I wanted Grant to clean up his problems and try to get back to work. That plea did not work. The problems didn’t get fixed, so I quit – and that was the end.”

Did you start working on your first solo album, Workbook, right away?

“I left music at first. I applied to the Parks Department for a job as a junior ranger and I moved up to a farm in northern Minnesota. I sat there for a year, re-learned guitar, and wrote music for myself. I didn’t know what I was doing.

“I just wanted to play guitar and be away from everything I’d been around for the last eight years. I was healing myself and expanding my musical vocabulary. And lo and behold, we have Workbook.”

Was abandoning the Ibanez a part of that change?

“It came out of a desire to progress and change. And that’s when I moved to the blue Stratocaster that I picked up at the music shop in Forest Lake [Minnesota]. It has a maple neck and the Lace Sensor pickups. It has a whole different touch and a whole different neck and body shape, and that led me on a new path.

“I was listening to a lot of world music and Appalachian music, Depression-era songwriting and bluegrass. All these different things lined up in my head with the direction I was already going. I started to free myself of who I used to be and work on who I wanted to be. Part of that growth came from being in a rural environment that was smaller than the small farm town where I grew up.”

The album is rich with discovery, but it echoes with loneliness and isolation.

“I didn't have a destination in mind, so I was working in the dark and finding things out as I went along. Eight months or so into this new life, I had a good sense of what I was working on and the different styles of songs I was writing, and I could tell which songs were good.

“Workbook is a very genuine record. What you hear is where I was. It’s the sound of somebody trying to figure out what the next part of their life is going to look like while also mourning the loss of what came before that.”

You followed Workbook with the much heavier and angrier Black Sheets of Rain. What led you from a largely melancholy album to a torrent of unfiltered rage?

“The density of Black Sheets of Rain is a direct result of the touring I did for most of ’89 with [ex-Pere Ubu bassist] Tony Maimone and the late Anton Fier [ex-Golden Palominos]. There was a heaviness to the way we played together that I loved. The Workbook songs got heavier and heavier the longer we played them. And that’s the sound we had when we went into Black Sheets of Rain.”

Were there other reasons Black Sheets of Rain was so bleak and despondent?

“I was in a relationship for six years that ended, so that definitely gave some brush to the fire. Neither Workbook nor Black Sheets are terribly happy records. But Black Sheets was influenced by a relationship ending and the environmental changes I underwent when I moved out of Minnesota to Hoboken, New Jersey, and then to Manhattan and Brooklyn.

“I really believe the time, place, and environment you’re in are so key to the music you make. Workbook was an open project for me. Black Sheets was more claustrophobic, as was my living situation.”

Having done two solo albums, when did you decide to start another band?

“The day before Sugar played its first show. The Black Sheets campaign was over by the end of 1990. I spent all of ’91 doing solo touring – just me and a 12-string. I went on the road for three weeks at a time, then I went home for a couple weeks and wrote a batch of new songs.

I looked down on the table and there was a sugar packet. That was the moment when those songs went from being on the third Bob Mould solo album to being on a record by a band called Sugar

“I’d play them on the road for three weeks and then do the whole thing again. That went on for nine months before I started looking for a rhythm section. I chose David Barbe [ex-Mercyland] on bass and Malcolm Travis [ex-Zulus] on drums, and we got together in Athens, Georgia, in the back of a shop called Snow Tire, which was across the street from the 40 Watt Club.

“On the last day of rehearsal, the owner of the 40 Watt Club, Barry Green, came over and said, ‘I know you’re taking off, but we had a band cancel for tomorrow night. Do you want to play a show before you go?’

“We went to Waffle House to have breakfast and talk about it, and I looked down on the table and there was a sugar packet. That was the moment when those songs went from being on the third Bob Mould solo album to being on a record by a band called Sugar.”

Did Sugar feel like a real band from the start?

“We got along well, and after three weeks of playing with them and doing that show, it was clear we played together well. I was definitely the band leader and I wrote the songs. But yeah, it felt like a band because we were all applying equal intent and purpose into the music.”

Sugar’s first album, Copper Blue, was a poignant blend of poppy alt-rock that was better produced than Hüsker Dü’s albums and seemed more musically cohesive. Seven months later, you released the more aggressive, cynical Beaster EP. Was that a reaction to the mainstream success of Copper Blue?

“No, we did both recordings in one session and we played the Beaster songs at that very first show we did. All the heaviness that became Beaster was already separated out as the last 20 minutes of that set. A fair amount of it was formed as instrumental music with improvisational vocals that then came into focus as actual lyrics during the overdub session for Copper Blue.”

That’s an incredible amount of material for one session.

“Those are just the 16 songs you’ve heard out of 30 we recorded. Many of them ended up as B-sides, and I have no idea where they went.”

You did one more album with Sugar, 1994’s File Under Easy Listening. After that, you went back to making solo albums and experimenting with a variety of music genres, including electronica, new-wavey rock, and jangly pop. Do you enjoy the freedom of doing solo albums?

“I like having the freedom to do what I want. In 1996, I did a self-titled solo record written mostly on bass guitar, where I played everything. In 1998, I did The Last Dog and Pony Show, which was my way of letting people know I was going to be moving on from being this rock guy and I was going to make a different life for myself musically.

The record goes through three distinct phases. There’s a lot of uncertainty. There's a lot of dark time. And then there’s a lot of bright time

“I got pretty deep into electronic music and made some more synthetic-sounding records, which was fun. I moved to D.C. and got together with a [dance music producer] named Richard Morel, and we started a DJ party called Blowoff that went for 11 years. Richard and I wrote a record together [Blowoff].

“And then I started easing back into guitar electronic music and then closer to guitar rock with [2008’s] District Line and [2009’s] Life and Times, leaving some of the synthetics behind. And then we got to 2012’s Silver Age, and that’s where I began working with Merge Records. We made five records in eight years with [ex-Verbow] bassist Jason Narducy, and [former Superchunk] drummer Jon Wurster.”

You put out a scathing political album, Blue Hearts, in 2020. Your new album, Here We Go Crazy, is lighter on politics and includes themes of hope and survival.

“It’s the give-the-people-what-they-want record. The familiarity of sounds and themes are there. I was putting all these songs I came up with together in the context of a big songbook and seeing how they held up against my prior work. And people let me know what they liked. So if it feels like an amalgam, it probably is. But there’s a difference.”

How so?

“It’s a wiser perspective. It’s an older perspective, and it's a very simple perspective. It’s a super-simple record. All I do is play a rhythm guitar and sing. Some of that again came from the changes in my environment. I started spending a fair amount of time in Southern California in the desert in wide-open spaces. And that’s a different way of life than being in San Francisco, Berlin, D.C., Minnesota, New York, or the Adirondacks. Maybe it lent itself to a different type of adventure.”

Is it a more hopeful record for you? Has that angry, closeted young man from the hardcore scene of the early Eighties been replaced by someone more content and optimistic?

“Probably, but I don't think that’s something I was aspiring to put into the songs. I just think the chemistry of life forces things on you. The record goes through three distinct phases. There’s a lot of uncertainty. There's a lot of dark time. And then there’s a lot of bright time. It's a three-act play. It’s real simple. There’s nothing complicated about this record. And that’s really where I am in my life right now.”

- Here We Go Crazy is out now via BMG.

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.