The greatest guitar albums of the ’80s: the rise of the next-gen guitar hero

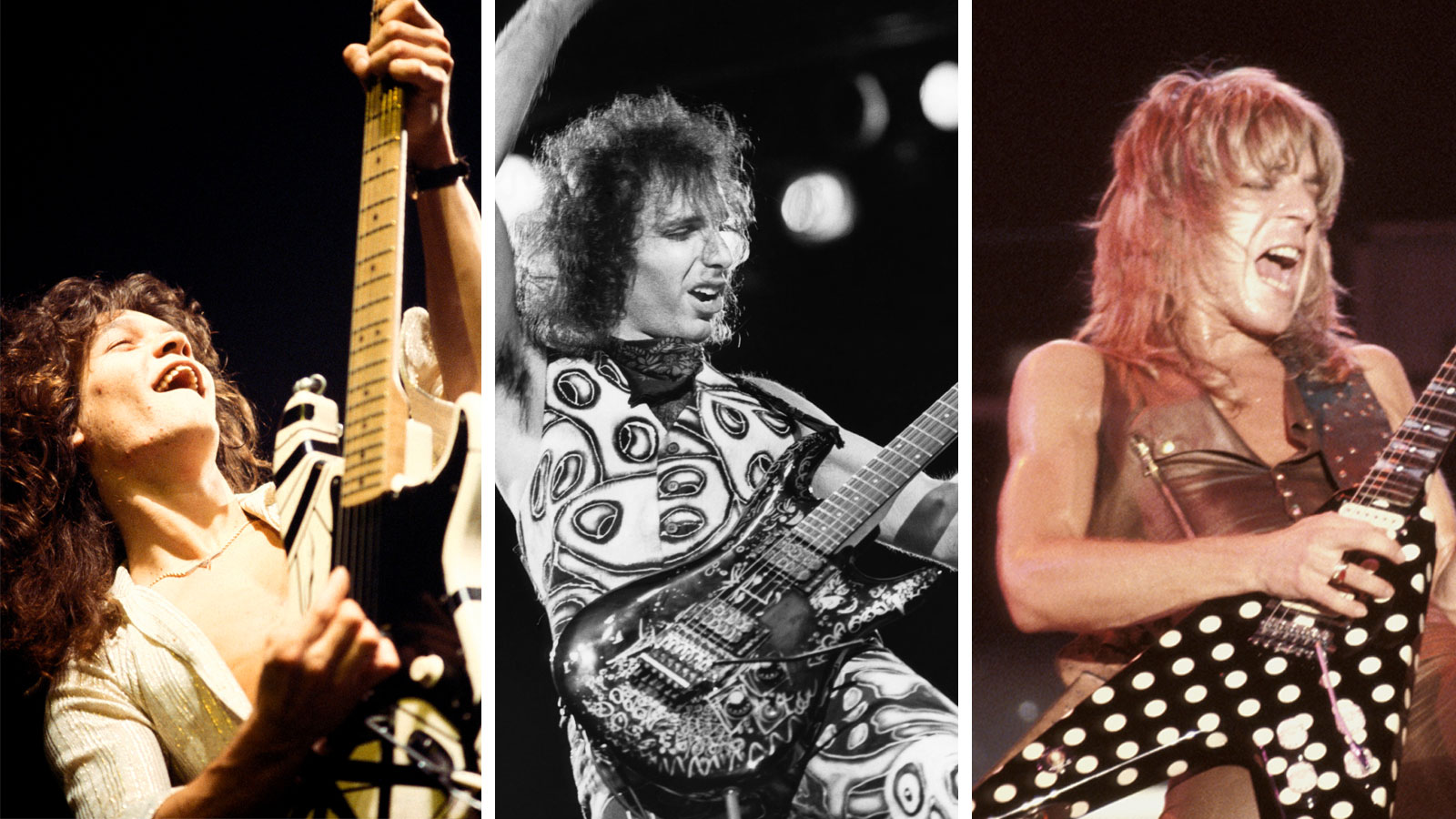

We examine the forward-thinking era that gave us monster records from Slash, Metallica and Randy Rhoads – and Joe Satriani tells us what made Van Halen's 1984 such a game-changer for guitarists

- 10. Iron Maiden – The Number Of The Beast (1982)

- 9. Prince – Purple Rain (1984)

- 8. Dire Straits – Brothers In Arms (1985)

- 7. Ozzy Osbourne – Blizzard Of Ozz (1980)

- 6. Joe Satriani – Surfing With The Alien (1987)

- 5. Stevie Ray Vaughan And Double Trouble – Texas Flood (1983)

- 4. AC/DC – Back In Black (1980)

- 3. Metallica – Master Of Puppets (1986)

- 2. Guns N’ Roses – Appetite For Destruction (1987)

- 1. Van Halen – 1984 (1984)

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Stevie Ray Vaughan reignited the blues. AC/DC delivered the biggest selling rock album of all time. New guitar heroes rose up – Slash and Joe Satriani among them. But if one guitarist owned the ’80s, it was Eddie Van Halen...

10. Iron Maiden – The Number Of The Beast (1982)

Some critics and industry bods genuinely thought metal was over by the early ’80s, and guitars were outdated. The Number Of The Beast definitively proved it was only just getting started. The giants of the ’70s were one-guitar bands, but in Maiden, Adrian Smith and Dave Murray’s Thin Lizzy-inspired harmonies made it compulsory for metallers to have two guitarists.

Their tone, powered by DiMarzio Super Distortion pickups into Marshalls boosted with overdrive pedals, was the metal recipe for most of the decade. Murray and Smith’s fluid soloing kept one foot in the blues but nodded to Ritchie Blackmore, upping the tempo for the new decade.

9. Prince – Purple Rain (1984)

Steve Vai once said Prince had no right to play guitar so well on top of his other talents. Purple Rain distilled that genius. On opener Let’s Go Crazy, a better rock/RnB crossover than Beat It (yeah, we said it), Prince riffs with the best, lays down soaring bends, and closes with an outrageous burst of wah-soaked shred worthy of an Ozzy album.

An octaver-aided shred frenzy opens When Doves Cry, and Darling Nikki’s guitars and lyrics are almost equally filthy. The matchless title track unites Wendy Melvoin’s gorgeous but finger-breaking add9 chords with Prince’s rapturous final solo.

8. Dire Straits – Brothers In Arms (1985)

Mark Knopfler’s guitar sound on Money For Nothing was actually an accident. Having set up the session the night before, producer Neil Dorfsman found an SM57 mic pointing at the floor when he arrived. Before he could fix it, Knopfler’s tech Ron Eve came on the talk back mic insisting they left it because the tone was amazing. Despite drawing detailed diagrams, Dorfsman could never repeat the effect.

Knopfler’s steadfast refusal to buy a pick means clichés about tone being in the hands are even more true than usual

Dorfsman says Money For Nothing used a Morley wah, Laney 2x12 combo, and a Les Paul Jr. The rest of the album was largely made with Knopfler’s Schecters and his 80s Les Paul Standard. Although Knopfler was an early adopter of the Soldano SLO100, it’s likely his main amp for Brothers was still his Marshall JTM45.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The title track tone comes from a cranked amp, with the Les Paul’s volume and tone backed off to create the dark, touch sensitive sound on the album. Walk Of Life is a distinctively Telecaster approach, while Strat-style guitars dominate elsewhere. The National resonator on the album’s cover only sees service on The Man’s Too Strong.

Knopfler was keen to try new technology, with Brothers In Arms being an early all-digital production. He used a Pensa-Suhr R Custom synth guitar controller to trigger sounds on a Synclavier synth – as seen in the video for So Far Away. Knopfler’s steadfast refusal to buy a pick, though, means clichés about tone being in the hands are even more true than usual.

7. Ozzy Osbourne – Blizzard Of Ozz (1980)

On the 1978 Never Say Die tour, openers Van Halen made the tired and increasingly dysfunctional Black Sabbath look like dinosaurs. When singer Ozzy Osbourne was fired by Sabbath the following year, he assembled a line-up that would never be embarrassed like that. Crucially, he found the one guitarist in LA who could rival EVH – Randy Rhoads.

Although frequently compared, Rhoads’ and Van Halen’s guitar styles are not very similar beyond the fact they both tapped and played fast. Ironically, the Dutch-born Van Halen sounded much more American, while the Floridian Rhoads’ classical influences had more in common with European guitarists. The Van Halen brothers had tons of swing, but Rhoads played much straighter. This was perfect for Ozzy’s solo debut, Blizzard Of Ozz, which came on like a jet-fuelled Black Sabbath.

For the recording of this album, Rhoads had not yet received the white modified Marshall he is known for, and instead used a rented Marshall JMP 1959 head. The amp was run relatively clean, with most of the crunch coming from his MXR Distortion+, enhanced by an MXR 10-band EQ with a strong mid boost centred at 500hz. Most guitarists would struggle through such an unforgiving setup, and it’s wild that Rhoads delivered those pinched harmonics and punishing legato lines so confidently.

The ’80s dawned with great guitarists in abundance, but Randy was clearly top of the pile. As neo-classical guitar got huge, Blizzard Of Ozz stood out for its melody, finesse, and great songs.

6. Joe Satriani – Surfing With The Alien (1987)

You can’t go platinum playing guitar instrumentals – it’s just not done. But Satriani did it with Surfing With The Alien, charting two rock radio singles along the way with the title track and Satch Boogie.

Joe’s virtuosity put him on guitar magazine covers immediately, and his warp-speed legato was the latest evolution of shred. But it was really his sense of melody that drew audiences. There were far more technical guitarists releasing albums in the aftermath, but none of them had a song as good as Always With Me, Always With You.

Joe’s virtuosity put him on guitar magazine covers immediately, but it was really his sense of melody that drew audiences

The guitars were recorded direct with a Rockman Headphone Preamp, and every song except Satch Boogie features a drum machine. It’s remarkable how much groove Satch extracted from those unpromising beginnings. Incredibly, all the solos except Crushing Day are improvised, showing Joe could think melodically even on the fly.

His tapping approach on Midnight was clearly Van Halen-inspired while doing something original with the technique. On the title track, Joe tapped with a pick, allowing faster taps than are otherwise possible, an approach that influenced his former student Kirk Hammett.

Surfing With The Alien stays interesting because Joe uses a range of modes and harmony to evoke different moods. The major climax of Always With Me is all the more joyous for the contrasting harmonic minor section that precedes it. The album remains the benchmark for instrumental rock 35 years later.

5. Stevie Ray Vaughan And Double Trouble – Texas Flood (1983)

Stevie’s guitar sounded so good on Texas Flood that he single-handedly changed the conventional wisdom about guitar strings. Despite most of the other records on this list being recorded with strings so thin you could barely see them, SRV convinced a generation to string their axes with suspension bridge cables in a quest for tone.

It was the ferocity of Vaughan’s attack and his unbelievable swing that mattered, though. The heavy strings were just there to take the punishment from his picking hand.

In a regular blues shuffle, the second eighth note comes slightly late, perhaps 60 per cent of the way through the beat, creating the bounce. Stevie, though, would hit it 70 per cent of the way through the beat, for a driving hard swing that few guitarists can replicate. Combined with his ability to rake through every note of a riff, it was an extremely aggressive take on the Texas shuffle that immediately converted rock fans.

Here was a new talent with the range, skill, and excitement to bring blues to an entirely new audience

Guitarists sometimes imagine that the hallowed SRV tone is in the gear. It doesn’t help that one of the amps was an unobtainable Dumbleland Special (if you can find one for sale, expect a $50k price tag).

The Stevie connection also saw the prices of 1980s Ibanez Tube Screamers skyrocket, prompting Ibanez to reissue them. As with all these sounds, it’s much more about how you play. Who do you imagine would sound more like SRV – you playing through his rig, or him playing through a cheap amp?

Extreme volume definitely helps them. Such was the fire, passion, though, and Stevie’s Strat was able to sustain so much because of the coupling of the amp and pickups at intense levels. Although his amps’ tones were quite clean, his Fender Vibroverb amps were adding some breakup and a lot of valve compression.

Conventional wisdom is that Stevie used the Tube Screamer as a clean boost, with the drive at or close to zero and the level cranked. That does sound great, but it’s not the only way he used them: he often had two running at once, which would inevitably add dirt, and with high-headroom amps he would sometimes increase the drive on one or both of them.

Stevie’s influences were not hard to spot – Hendrix, Albert King and Lonnie Mack chief among them. Such was the fire, passion and sheer quality of Vaughan’s delivery, though, that no one could dismiss him as a mere imitator.

Testify, an Isley Brothers song that Hendrix had played during his stint with the group, became an earth-shaking instrumental in Stevie’s hands. Buddy Guy’s Mary Had A Little Lamb was similarly beefed up, and the fact the young Vaughan’s playing easily stood comparison to those giants showed how special he was.

At the close came Lenny, an instrumental for his wife that was as delicate and subtle as Rude Mood was raw and aggressive. That Vaughan was capable of such contrast signalled his depth. Here was a new talent with the range, skill, and excitement to bring blues to an entirely new audience.

4. AC/DC – Back In Black (1980)

Writing about how Back In Black sounds seems almost inappropriate. The raw, visceral energy coming from every riff connects to a primal instinct deeper than language. This is gut-level music, not brain music.

That’s not to say there are no subtleties. The title track has a straight groove, but Angus Young swings the descending lead lick in the riff, a nuance almost everyone misses.

By running their amps just past the point of breakup, Angus and brother Malcolm achieved sensitive guitar tones that magnify all the details in their playing

By running their amps just past the point of breakup, Angus and brother Malcolm achieved sensitive guitar tones that magnify all the details in their playing. The breakdown before the last chorus of Shoot To Thrill sees Angus brushing his strings as lightly as possible, and you can hear the difference in how hard he plucks each one.

The tone is clear enough to hear every note in chords, and the arpeggiated choruses of You Shook Me All Night Long are positively jangly. Yet the intro chords of the title track crunch like a dinosaur eating cars. This range of tones comes almost entirely from Malcolm and Angus’ picking dynamics.

Thanks to Filippo Olivieri’s forensic studies, we know that a contributor to Angus’ tone was the Schaffer-Vega wireless he used even when recording. The receiver included a preamp which restored frequencies lost in transmission but also boosted the signal in unique ways. But what you really need is a picking hand spiritually synced to the groove. We can’t explain it. Just turn it up.

3. Metallica – Master Of Puppets (1986)

Most bands are lucky to have one great guitarist, but Kirk and James both star on the greatest thrash album of all time. Hetfield’s right hand is like Cristiano Ronaldo’s right foot, a marvel at the pinnacle of achievement in its field. If the timing is at all off when double tracking, the attack of each note gets ‘smeared’, losing the crunch.

Hetfield triple-tracked his guitars with laser-guided precision, some of the tightest and most brutal rhythm playing ever laid down. It helped that the band had riffs to burn, churning through an album’s worth in the title track alone.

One consistently underrated aspect of Kirk Hammett’s playing is his ability to create melodies over clean breakdown sections. The harmonised lines over Hetfield’s arpeggios in the title track are a moment of beauty amidst brutality, and it makes everything sound more crushing when the band starts breathing fire again. Kirk’s whammy bar action is also top notch, in a decade of tremolo shenanigans.

The Puppets guitar tone was transitional between their early, nasal, Marshall-and-Tube Screamer tone and their later scooped Boogie sound. Kirk and James slaved the preamp from Mesa/ Boogie Mark IIC+ heads into the power amp of a Marshall 2203.

James had not yet discovered EMG pickups, and was using a Jackson King V equipped with Seymour Duncan Invaders. Kirk mainly used a Jackson Randy Rhoads with EMGs, but his stock Gibson Flying V appears on some solos.

2. Guns N’ Roses – Appetite For Destruction (1987)

Mid-’80s Los Angeles had two kinds of guitarist: shredders with amazing technique but no feel, and posers with none of either. Into this void came Slash, reinventing classic rock guitar on Guns N’ Roses’ debut record Appetite For Destruction.

Other bands talked tough, but singer Axl Rose actually sounded ready to jump off the stage and mess you up, and Slash’s solos had the attitude to back it up. After Axl yells “why don’t you just... f**k off?” in It’s So Easy, Slash’s grinding two-string bend repeats the invitation. When Axl threatens “I wanna watch you bleed!” in Welcome To The Jungle, Slash delivers double stops tough enough to make it happen.

80s records could sound mechanical, but Appetite was deeply human, as the accelerating outro to Paradise City showed

Equally important was rhythm guitarist Izzy Stradlin. He and Slash proved themselves easily the best riff writers since AC/DC, and the interplay between their parts was essential to Appetite’s magic.

Judas Priest bashed out identical riffs in unison, and Def Leppard orchestrated unique parts for each guitarist. Slash and Izzy found another way, each of them often playing his own interpretation of the same riff. This created a dynamic push and pull between the parts. ’80s records could sound mechanical, but Appetite was deeply human, as the accelerating outro to Paradise City showed.

Appetite also sounded honest. Some ’80s ballads sounded like the result of a board meeting to produce a hit single, whereas Sweet Child O’ Mine was naturally melodic. Slash’s ear for melody produced hooks you could whistle, giving Paradise City, Sweet Child O’ Mine and Welcome To The Jungle some of the decade’s most memorable single-note riffs.

Slash’s solos showed the influence of Michael Schenker, Angus Young and Jimmy Page, but he had the speed to impress in the decade of Vai and Yngwie. He never sounded like a shredder, though. He had controlled sloppiness like Keith Richards and Joe Perry that just sounded cool.

He was also more rhythmically interesting than the shredders delivering hails of unbroken 16th notes or sextuplets. Even Slash’s breakneck licks in Nightrain and Paradise City use a variety of note lengths and articulations.

Mix engineers Steve Thompson and Michael Barbiero wisely left the guitars raw, and this helped Appetite to stay relevant even through the 90s, when most 80s records sounded painfully dated

As with Van Halen’s first album, Appetite’s guitar tone is shrouded in myth and legend because the rented modified Marshall Slash used was later stolen. But the important thing was that it sounded like a guitar amp, rather than a signal that had been fed through so many digital processors it barely resembled the original source.

Mix engineers Steve Thompson and Michael Barbiero wisely left the guitars raw, and this helped Appetite to stay relevant even through the ’90s, when most ’80s records sounded painfully dated.

In hindsight, Appetite started paving the way for the ’90s even as it embodied ’80s excess. It spearheaded a return to live sounds and Les Pauls and away from day-glo pointy headstocks. Guns N’ Roses represented authenticity, a love of music, and real emotion at a time of cynicism, and their debut is a testament to the life-affirming powers of rock’n’roll.

1. Van Halen – 1984 (1984)

Van Halen’s sixth album, 1984, was the climax of a battle for creative control between Eddie Van Halen and the band’s producer Ted Templeman. After 1981’s Fair Warning – Van Halen’s heaviest album – produced no hit singles, Templeman pushed for covers on 1982 follow-up Diver Down. It yielded hits, but Eddie was unhappy.

“I would rather bomb with my own music than make it with other people’s music,” Eddie told Guitar World in 2014. “Ted felt that if you redo a proven hit, you’re already halfway there.”

To wrest control from Templeman, Eddie and engineer Don Landee converted a racquetball court at Van Halen’s house into a studio. They named it 5150, and the 1984 album was its first project. Ironically, the album made entirely on Eddie’s terms became Van Halen’s most commercially successful effort. Templeman resisted recording at 5150, but relented after he heard the song Jump. “He didn’t care much about the rest of the record,” said Eddie. “He just wanted that one hit.”

Jump sounded really fresh. The simple major chords that we’ve heard a million times just for some reason sound new.

Joe Satriani

With Eddie, a classically trained pianist, playing the main riff on synthesizer, Jump put a new twist on Van Halen’s sound. As Joe Satriani says now: “Jump sounded really fresh. The simple major chords that we’ve heard a million times just for some reason sound new.

“I would say that’s like Mozart. There’s a history of amazing classical music before him, so what did he do? He used the same chords as everybody else, but the way he did it made you go ‘Oh! I like the way he goes I-IV-V.’ Jump has that same thing. It’s just I-IV-V, but it sounds great.”

With Templeman pacified, Van Halen got serious. Limited space at 5150 made for an unusual working environment. The Marshall Plexi sat in one corner behind isolation panels, and Eddie sat on a stool in front of brother Alex’s drumkit and did not even wear headphones. There wasn’t space for cymbals, which were overdubbed later. Only the snare was live; Alex used electronic Simmons drums for everything else.

“Can you imagine what it sounded like in the room?” laughs Satriani. “This is insane. He’d do a drum fill and where there should be a crash at the end, there’s nothing. How did they work that out? Just the monitoring, so that they could do something like Hot For Teacher and make it sound so perfect?”

What makes this album so interesting is the fact that there are guitars that are not totally in tune - but good luck trying to get as good a take as that!

Joe Satriani

The visual connection between the Van Halen brothers was essential. As Eddie recalled of Hot For Teacher: “I distinctly remember sitting in front of Al on a wooden stool and playing that part during my solo where it climbs. Well, I can’t count, so Al needs to follow me. I’d sit right in front of him, and then he’d look at me like, ‘Now!’” Satriani is thrilled by this story. “No wonder it sounds like so much fun!” he enthuses. “They were sort of autonomous and yet they were totally linked together.”

As Satriani sees it, the sound of the brothers playing live was essential to the Van Halen sound. “That sound of Alex’s snare drum, I just hear that as something that pulls the whole album together. There are a couple of drummers out there that do that. Watching the Get Back documentary [2021], I realised The Beatles were not The Beatles until Ringo started playing.

“When he was off having a cup of tea, it just sounded like John, Paul, and George as individuals. It didn’t sound like The Beatles. Ringo starts to play and it’s this gigantic thing. Van Halen is the same way. We’ve all heard Eddie jamming with other people and it’s nowhere near the same.”

Joe discussed the recording of 1984 with Van Halen bassist Michael Anthony when they worked together in the supergroup Chickenfoot. Since 5150’s live room only had space for Eddie and Alex, Anthony overdubbed his bass later.

“Mike told me every song you’d have to find out where Eddie was tuned, because you never knew what take they used and whether anything was tuned at the time,” Joe says. “What makes this album so interesting is the fact that there are guitars that are not totally in tune – but good luck trying to get as good a take as that!”

Eddie’s 1984 tone is distinct from his early sound, but it used largely the same gear. The Frankenstrat was largely retired for this album in favour of the banana-headstocked Kramer 5150, but the magic Marshall Plexi was still his only amp. Eddie did use his Eventide harmoniser on every song, but it was not as prominent as it would become on later albums. “I used it mostly to split my guitar signal so it came out of both sides,” he commented.

It’s a different kind of music altogether. It’s both whimsical and deadly serious, and you just have to be so good to pull that off

Joe Satriani

The guitars are still single-tracked with few overdubs, making it unique among rock albums of the time. As Joe comments: “There’s not like rhythm guitar left and right. I’m always adding a Tele and a Strat and a Les Paul, but because David Lee Roth’s voice was so charismatic, they didn’t have to. They left space for each other.”

Templeman’s lack of concern for album tracks left Eddie and Alex free to stretch themselves creatively. As Joe notes: “When you make albums, there are songs that the band likes but from the production point of view it doesn’t have commercial potential, suddenly people start to work on it differently. Everyone plays differently. They say, ‘Well it’s not gonna be a single so we can do this instead of having to edit that part.’

“I love House Of Pain so much. It’s not as complete as Jump or Panama, where you can tell they worked on it because it had single potential. The verses are so out there. When I try to imagine one of the four parts not being there, it doesn’t work. I remember just listening to that over and over again, thinking ‘This is a moment.’

“What I really like about that first the first version of Van Halen was that they all seem to be playing separate parts with separate accents, yet they came together so well. Eddie never really went for that triple-tracked, all playing the same thing, the drums and bass are doing the same thing. It’s a different kind of music altogether. It’s both whimsical and deadly serious, and you just have to be so good to pull that off.”

Joe still recalls Van Halen’s seismic impact on America’s guitarists. “When Eddie came on the scene it scared the shit out of so many guitar players,” he says. “I saw it as a total vindication of what I liked to play and what I liked to listen to, whereas people in other styles were feeling, ‘This is bad competition. I don’t want to have to deal with someone who can play that good.’ I always thought Eddie is going to be great for guitar. I was keen not to copy something that Eddie had done. Like, ‘I’m not going to get in his territory. What’s my contribution?’

“When I wrote the two-handed piece Midnight for Surfing With The Alien I was thinking, ‘Guys like Eddie and other two-handed players – what did they not do?’”

For Joe Satriani, 1984 exemplifies great music. “The music we listen to decade after decade is the stuff with character and love in it. You can’t get that just by sitting down with the metronome and trying to get one click faster. The thing we should be practising is just playing music. Eddie and Alex jammed for hours until they hit upon something so unique that is so perfectly natural. It jumps out of the album.”

Jenna writes for Total Guitar and Guitar World, and is the former classic rock columnist for Guitar Techniques. She studied with Guthrie Govan at BIMM, and has taught guitar for 15 years. She's toured in 10 countries and played on a Top 10 album (in Sweden).