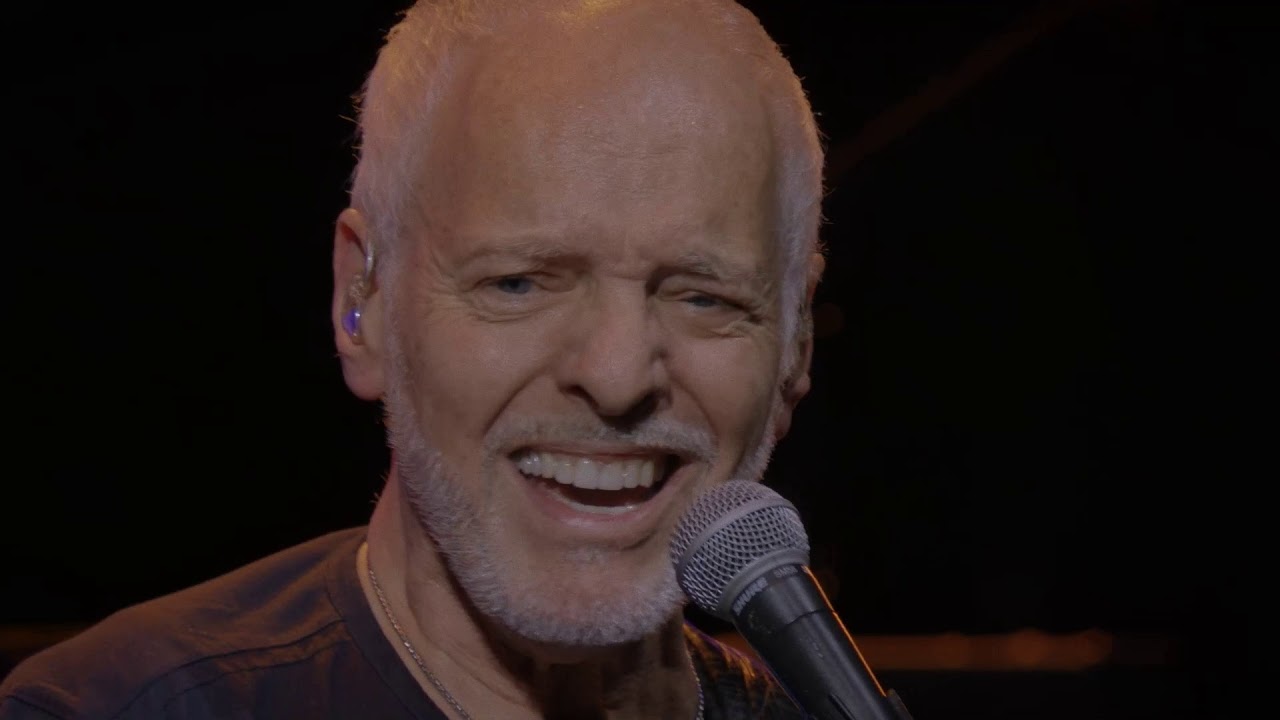

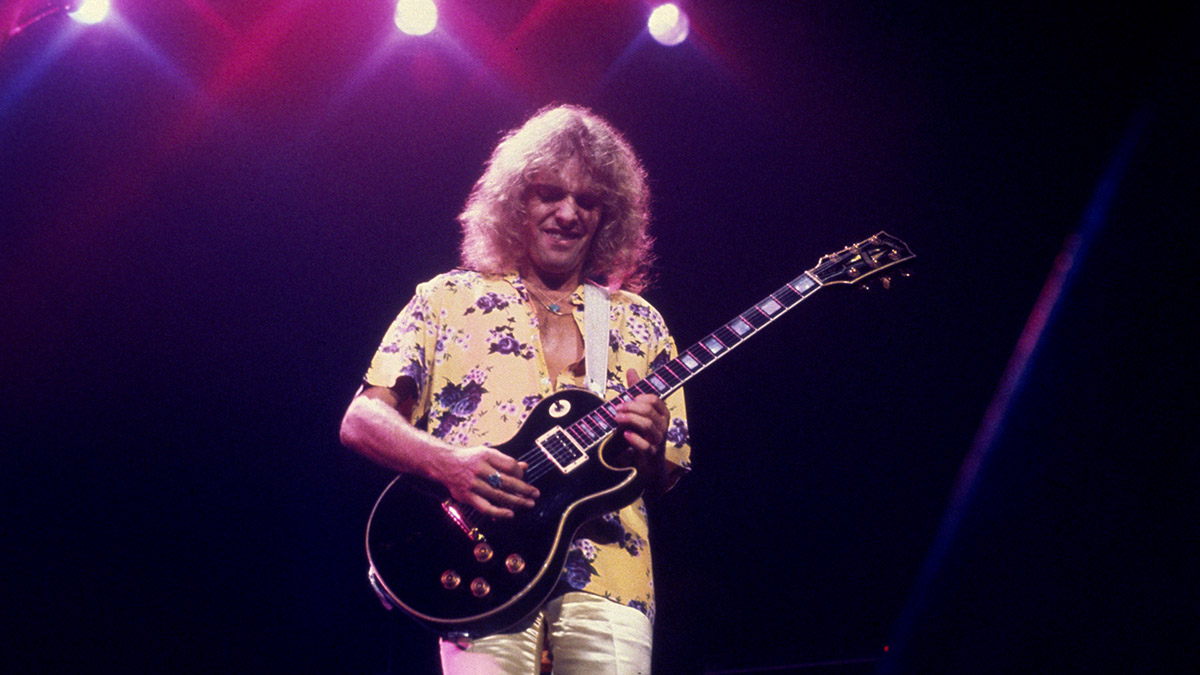

Peter Frampton on the highs and lows of his remarkable guitar journey, meeting George Harrison, and how David Bowie made him cool again

From early pop stardom with The Herd to Frampton Comes Alive! and finding salvation in Bowie’s band, Frampton reflects on a rollercoaster career and the darker side of fame…

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Peter Frampton is currently on a farewell tour having been forced into retirement owing to the onset of Inclusion Body Myositis, a degenerative condition that affects the muscles and looks to end his playing career for good. However, rising above the tragedy, he’s in high spirits when we strike up our Zoom call.

We mention that it’s been a long time since we saw him perform on this side of the Atlantic: “We were supposed to be there in May 2020,” he says ruefully. “Then, of course, the pandemic shut us all down…” And thus the performances rescheduled for this November in the UK take on an extra level of significance.

Once hailed as the most famous artist in the world, he tells us how those heady peaks were a mixed blessing and very nearly his undoing. But every story has its beginnings and Peter’s starts in the late 1950s…

What got you interested in playing guitar in the first place?

“Probably Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran and Lonnie Donegan first. Lonnie was the first person I saw on TV doing skiffle, then when he came out with Rock Island Line, it was starting to be more rockabilly. Then Cliff and The Shadows: I became obsessed.

“I wanted to be in The Shadows from when I was eight years old. From Living Doll on, it was like every kid that was musical wanted to be Hank Marvin. They were the instrumental Beatles. I can still play just about any Shadows number you’d care to mention, note for note.”

What was your first instrument? Obviously, you would have wanted a Strat, but they wouldn’t have been available in Britain at the time.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“No. I mean, the most I could have hoped for at the very beginning was a Höfner, a Futurama III or something. But no, when I was seven, my dad and I went up to the attic to get out our summer holiday luggage and I noticed this little leather case. I didn’t know whether it was a violin or what it was.

“I said, ‘What’s that?’ and he said, ‘Oh, your grandmother gave me this – she thought you might want to learn to play it one day. It’s a banjolele.’ My dad got it out and played a couple of chords on it, then I think we left it up there for a few months until I said, ‘Dad, can we get that instrument down?’

“That’s when I started. He showed me Hang Down Your Head Tom Dooley, Michael, Row The Boat, that kind of stuff. Once I’d mastered those pretty quickly, my parents thought, ‘Wow, he picked that up quick.’ I think they knew pretty early on they were in for trouble.”

And it was from here that you progressed onto guitar?

“Yes, when it was time for Christmas – it would have been 1958 – I asked Father Christmas for a guitar. I got a guitar and the world was my oyster at that point. I wanted to electrify it as soon as I could. I got all the magazines, the Selmer magazines, the Hofner, the ‘this, that, whatever’.

“I looked and there was a pickup that you could get to amplify an acoustic so I got one. Once I got the pickup, I said, ‘Dad, I need an amplifier.’ He said, ‘Well, I think we can plug you into the living room radio.’ He found out that even in those days there was an auxiliary input in the back. Bingo. I had an electric guitar – that was it.”

Were you eventually caught up in the British blues boom?

“Oh, yes. When I was in my teens, before The Herd, I was going up to see John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton. I saw Graham Bond with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce and Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band with Andy [Summers] on guitar. It was just a phenomenal time for music then because it was all so new, so there were no rules.

When I saw the Small Faces on Ready, Steady, Go! doing What’cha Gonna Do About It live, my jaw was on the floor because you couldn’t help but catch the fact that Steve [Marriott] was amazing

“We relied on the seamen coming in from America to bring albums because the BBC obviously wasn’t playing what we wanted to hear. You’d have Mantovani and then something else and then you might have a Cliff Richard track or something. I think we all relied on everybody saying, ‘Have you heard this album? I’ll lend it to you.’

“You’d have to give it back, but unfortunately I still have George Underwood’s Coral Records’ Buddy Holly, the very first album, George being David Bowie’s best friend for life and mine, too. I better bring that album with me [to the UK] to give it back to him. It’s only been 60 years…”

You ended up joining The Herd in 1966. How did that come about?

“Andrew Brown and Gary Taylor from The Herd came to see me play. We knew each other anyway because I’d sat in with The Herd when I was a little upstart. After the show they said, ‘Look, we’re reorganising the band. Would you come and play rhythm guitar for the summer?’ Then when I joined the band, it seemed like it changed almost overnight.

“They put me on lead guitar. Gary switched from lead guitar to bass. At the end of the summer they asked me, ‘Would you join the band?’ I said, ‘Well, my dad’s a teacher and my mum works in a school, so I don’t think that’s going to be happening,’ because I’d planned on going to music college, going back to the sixth form and all that stuff and getting my A Levels.

“Anyway, I really wanted to join the band so I popped the question to Mum and Dad together. Dad had smoke coming out from his eyes, his ears, his mouth, everywhere. Mum was going, ‘Leave it with me.’ They came back to me a little later and said, ‘Okay. We know this is what you’re going to do anyway so we’re going to say yes.’ My dad said, ‘But you’ve got to earn £15 a week minimum otherwise the deal is off.’”

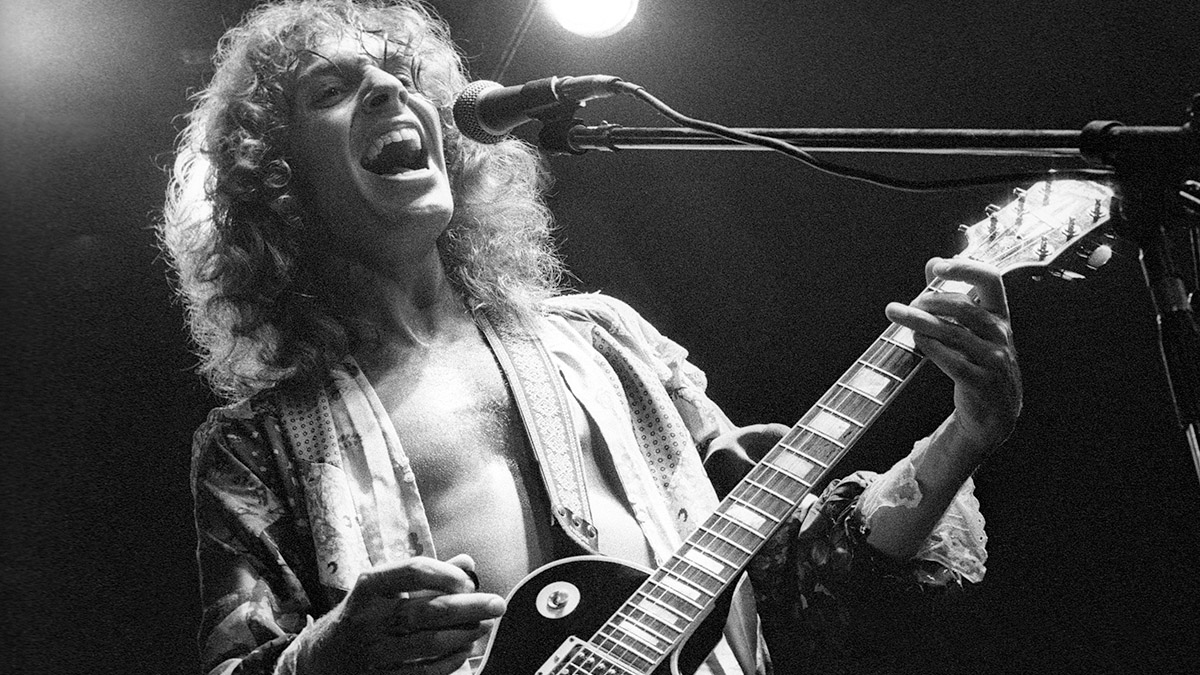

After quite a lot of success with The Herd, you joined Humble Pie.

“When I saw the Small Faces on Ready, Steady, Go! doing What’cha Gonna Do About It live, my jaw was on the floor because you couldn’t help but catch the fact that Steve [Marriott] was amazing. I said to myself, ’I want to join the Small Faces.’ Anyway, that wasn’t to be, but I left The Herd and I did get to go and do this week of sessions in Paris for Johnny Hallyday with Glyn Johns being the engineer/producer and Small Faces being the band and me being another guitar player. I think at that point Steve really wanted me in the band.

If I had stayed in the band, I would have still been in Humble Pie, I think. It was just I wanted to be in charge of my own destiny

“Anyway, we flew back from Paris with Glyn and he said, ‘Let me just play you this album. We just recorded and mixed this in 12 days. It’s a new band, but you might know the guitar player, Jimmy Page.’ He puts on Led Zeppelin I in his living room. Again, jaw to the floor but not so much for the guitar – it was Bonham that just floored me.

“As it got to the end of side one, the phone rang. It was Steve. He’d just got off stage at the Alexandra Palace and had done his last gig. He said, ‘Can I join your band?’ We had Greg Ridley and Jerry Shirley, and with a snap of the fingers we had a band. That was it. Humble Pie was formed. By the next week we were in Jerry Shirley’s parents’ front room with little tiny amps, practising.”

It must have been a tough decision to leave Humble Pie.

“Little things really are hard for me. Big things, I can really make a decision. I don’t think I’m cold-hearted or anything; I think that I’m able to change on a dime if I have to, if pushed. I just felt that the way we were going, which I loved, was a little harder-edged. I was riding the riffs just as much as Steve. I mean, I Don’t Need No Doctor is my riff.

“Stone Cold Fever, my riff, One Eyed Trouser Snake Rumba, my riff; Steve’s lyrics, though. Steve and I were starting to butt heads a little bit. I think I was coming into my own. Even though I knew that [Performance] Rockin’ The Fillmore would be our biggest record so far, I had no idea it would be their first gold record because I’d done a lot of the mixing with Eddie Kramer in New York for that album.

“But no, I just decided in the end that this would be the best time, before they really break. Otherwise, if I had stayed in the band, I would have still been in Humble Pie, I think. It was just I wanted to be in charge of my own destiny finally and not have the band.”

After four solo albums, you released the phenomenally successful Frampton Comes Alive! in 1976. It must be difficult to put into words the impact that had on your career.

“I have to use the word ‘surreal’ because four or five years beforehand I thought I’d made the biggest mistake of my career by leaving Humble Pie because Rockin’ The Fillmore was jumping up the charts all over the world. I thought, ‘This is it. I’ve done well so far, but this is it.’

“But it was all up to me at that point, I realised. I thought, ‘If I play my cards right and I go out and do a lot of touring for this, maybe this will be my first gold record.’ A week later it was a gold record. It came out and just exploded.

Rockin’ The Fillmore was jumping up the charts all over the world. I thought, ‘This is it. I’ve done well so far, but this is it’

“All of a sudden I realised that I had a lot of friends that I didn’t have before. Everybody had their two cents to put in, especially the people that were rubbing their hands together like this because I suddenly became the hen that laid the golden egg.

“I went away over Christmas to the islands just to get some sun as I knew we’d be touring all year. I came back and not only did we have one show at Cobo Hall [Detroit], which I think is 8,000 capacity, we had three. Within 10 days it had gone from one to three shows. Then we sold out two shows at Madison Square Garden. Then I got the call: ‘Are you sitting down? The album is No 1.’ I couldn’t believe it. But on the next call I was told that I’d broken Carole King’s Tapestry album record and I was now the biggest-selling album of all time. And that’s when I got nervous…”

Why was that?

“Because I knew that I couldn’t follow it. That album took me six years to write; it was a live ‘best of’ up until that point. There is a number from Humble Pie, Shine On, I cherry-picked Wind Of Change, Frampton’s Camel, Somethin’s Happening… I felt I’d lost before I’d started after that phone call. That was when I think I started to over-imbibe and wanted to numb myself. The golden hen was now constipated…

“When I heard that the album was No 1, I think I went and sat down and wrote I’m In You, which is a great song. It shouldn’t have been the first single [of the album of the same name], but it’s a great song. It’s a great ballad because I was so up on everything. Then once I’d heard that I was the biggest, I hated hearing that. I think it shut me down creatively more than anything.

“Truth be known, I should have probably commissioned every great writer there is and sat down and written with all of them. That would have been the only way to have dealt with that situation. I didn’t want to make [the album] I’m In You. I didn’t even want to hand it in. I didn’t like it. I knew it wasn’t good enough, but everybody was ‘rush, rush, rush’.

“Everybody, one by one, would come to me with their own hidden agenda and say, ‘The longer you wait, the harder it’s going to be,’ and all that stuff. I wanted to wait until I had the best material I could come up with, however long that would have taken. It could have taken a year, it could have taken two years.

“Various things happened. I lost a cassette tape that had a load of ideas on it – that was devastating to me. I remembered some of them but not all of them. The bulk of my new material that I had up until that point disappeared. It was a painful record to make.”

Was I’m In You critically well received, do you remember?

“I don’t believe so. I don’t read a lot of reviews, especially when I know they might not be good. Even though I’m In You was a huge single in the States and the album went right up the charts straight away, things dropped off pretty quickly. The I’m In You tour was fine, that was good. Then after that, when that had sunk in, I think that’s when I started to lose a lot of audience. That was the situation. I felt like I was in a sinking ship.”

Looking back, what was that level of fame generated by Frampton Comes Alive! like for you?

“It’s very enjoyable to start with because you go to the front of the line, you get into the club, now you’re a celebrity or whatever you are. But it was the biggest album in the world so I guess that comes with it. Everybody wanted a piece of me, whether it was an autograph or whether it was some money.

“I was glad that we were on the road as much as we were at that time because I had the guys around me. But at that point, management was trying to separate me from my band so my band didn’t give me any bad info as far as they were concerned. My band was threatened and all kinds of stuff. Crew members were threatened, basically, not to talk to me. It was a lonely period.

“I remember my brother came to see me on the I’m In You tour in ’77. I was sitting in this ginormous suite. One of the high roller suites, whatever, somewhere in Vegas. I’m there with my tiny room service tray and all I hear is the knife and fork on the plate. It reminded me of that scene at the end of [the movie] 2001: A Space Odyssey.

“That was me now. Then my brother came in and sat on the other side of my table, and I started crying. I didn’t want to be on this tour, even though I’ve just said I loved being around the guys. But I could feel it slipping away. I was so tired. I was exhausted.”

How did you deal with the vacuum that happened after that time?

“It was a very difficult period for me because I had it in the palm of my hands, as it were. But once you experience it, you go, ‘Oh, well that’s good. I like that.’ Instead of going and working with as many writers as I could and getting a great producer in or having a different producer for every track on the next record, I just went back and thought, ‘Well I’ve done it all myself, I’ll do it all again.’ But I didn’t have the material.

“We were doing a lot of covers on the next record, Where I Should Be. It was hard. I got let go by A&M in ’80/’81, after The Art Of Control, which was obviously done by an artist who had no control over himself. I bottomed out there – I’m sure substances didn’t help. I have a family history of depression, it all comes into it. When you go that high, there is a pretty good likelihood that you’re going to go that low. I felt like I was starting again from a negative position.”

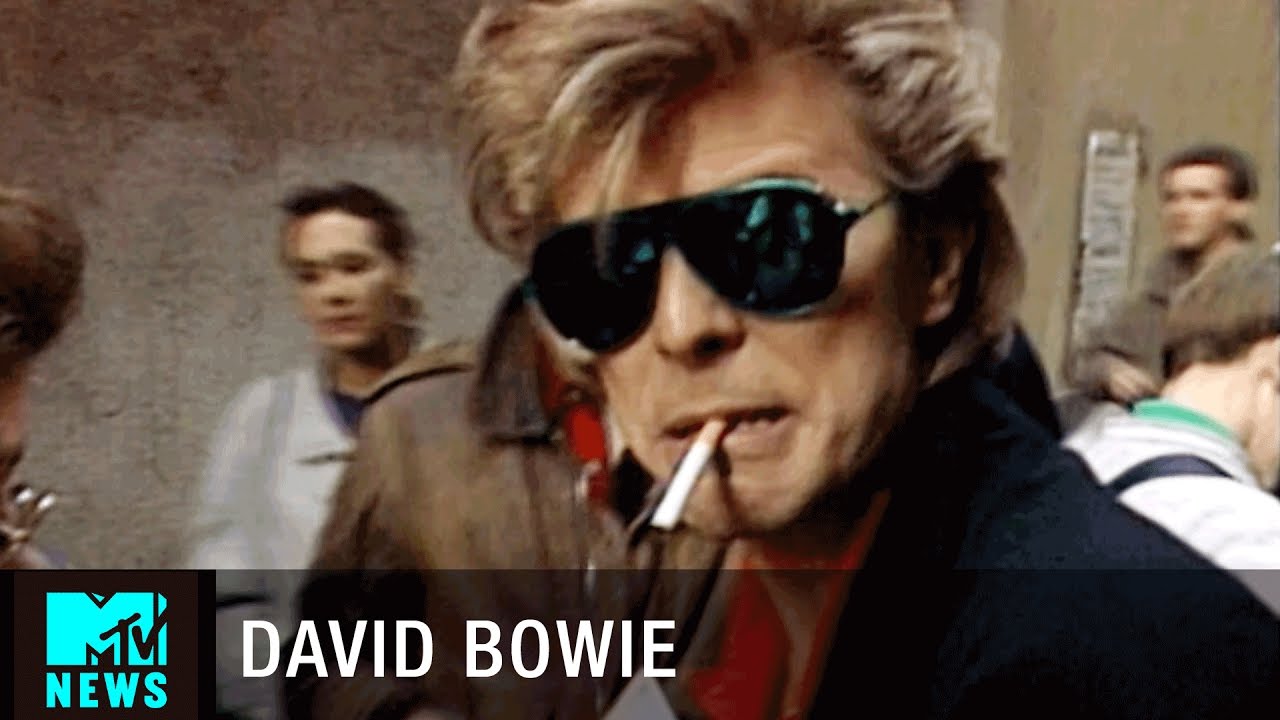

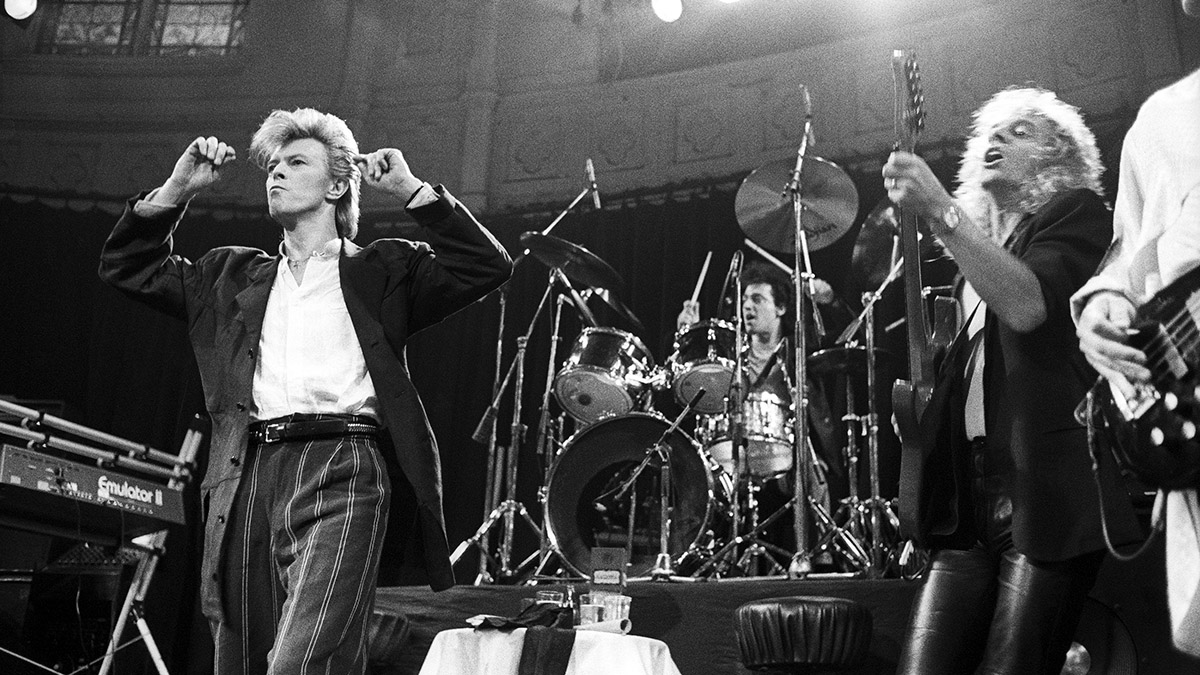

How did you come to do the tour with David Bowie?

“I did a record for Atlantic called Premonition [in 1986]. It still wasn’t a great record. It had much better material, but wasn’t where I should have been. That’s the album David Bowie listened to. He would check me out and he said, ‘Can you come and play some guitar for me?’

“That’s when I went to Switzerland and we recorded Never Let Me Down. Then he asked if I would be one of the guitar players on the Glass Spider tour, which blew me away. Finally, having been on the same stage the same evening many times before, I was going to be Dave’s guitar player.

“He could have chosen anybody. He’d had Stevie Ray Vaughan the album before, but he chose me. I can never thank him enough for that. He knew what he was doing for me before I knew what he was doing for me. It was a Dave plan.”

It sounds like you were much happier in that role.

“Oh, yes. That’s my comfy chair. I’ve always been more comfortable playing guitar, not singing – maybe the occasional song like in Humble Pie – but playing behind a great singer, a great frontman. But I wanted to do everything myself. It’s a juxtaposition between being in a band and following the consensus, and being a solo artist and making your own mistakes. I wasn’t doing very well at it and I think it was because the shock and awe of …Comes Alive! was always on my shoulder going, ‘Remember this?’ I’ve said it before, but it was a blessing and a curse.

“In the end, I’m so proud of it. It was a definite blessing because it made me fight for my career. It made me get up, brush myself off and do it again, work myself up the ladder. David inviting me to do the album and tour changed my credibility; I got my credibility back that I felt I’d lost when I’m In You came out. A teenybopper star, his length of career is about 18 months, whereas a musician’s career is a lifetime. I’m a musician first and foremost. David gave me back that credibility to continue and bring people back to me.”

After such a long and varied career, is there a moment that you’ll always remember if you could just pick one?

“Meeting George Harrison. I’m up in town at The Ship Pub on Wardour Street [in Soho, London] with Terry Doran, who was John Lennon’s assistant for years, and we’re just catching up. He said, ‘Do you want to come and meet Geoffrey?’ I said, ‘Geoffrey who?’ He said, ‘Harrison.’ I said, ‘Oh, they’ve all got code names, have they?’ I was shaking, literally. My first Beatles sighting or meeting.

“We walked into Trident Studios and there was George. He looks up from the console and he goes, ‘Hello, Pete.’ It was unbelievable that he knew who I was – a Beatle knew who I was. He comes round and we start talking. He goes, ‘Hey, do you want to play? We just wrote a song downstairs for Doris Troy. I’m producing her first album in a while. Come down and play.’

We walked into Trident Studios and there was George. He looks up from the console and he goes, ‘Hello, Pete.’ It was unbelievable that he knew who I was – a Beatle knew who I was

“I thought I was going to wake up and it was a dream. He gave me what I now know was Lucy, the red Les Paul that he used, but, more importantly, it was the one that Eric Clapton played on While My Guitar Gently Weeps. As I went to move my chair, I looked round and sitting right next to me was Stephen Stills. He had just written the song with Doris and George. Now I’m totally nervous.

“Anyway, we start it and I’m playing a very quiet rhythm. George goes, ‘No. Pete, I want you to play lead.’ I thought, ‘Oh crikey.’ I just played all these licks in the intro and between the vocals and everything. After the session, he came over to me and said, ‘Can you make the rest of the sessions?’ It blew my mind.”

With over 30 years’ experience writing for guitar magazines, including at one time occupying the role of editor for Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, David is also the best-selling author of a number of guitar books for Sanctuary Publishing, Music Sales, Mel Bay and Hal Leonard. As a player he has performed with blues sax legend Dick Heckstall-Smith, played rock ’n’ roll in Marty Wilde’s band, duetted with Martin Taylor and taken part in charity gigs backing Gary Moore, Bernie Marsden and Robbie McIntosh, among others. An avid composer of acoustic guitar instrumentals, he has released two acclaimed albums, Nocturnal and Arboretum.