“A good guitar solo should sound like an orgasm. I can hear it in Eddie Van Halen’s playing, and Jimi Hendrix. I live for the juicy notes”: Carlos Santana on playing like a soul singer and his visitations from B.B. King, Miles Davis and Stevie Ray Vaughan

Single-cuts are like merlot, solos are like grapefruit… the inimitable, peerless Carlos Santana shares stories from his legendary career and insights from the cosmos

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

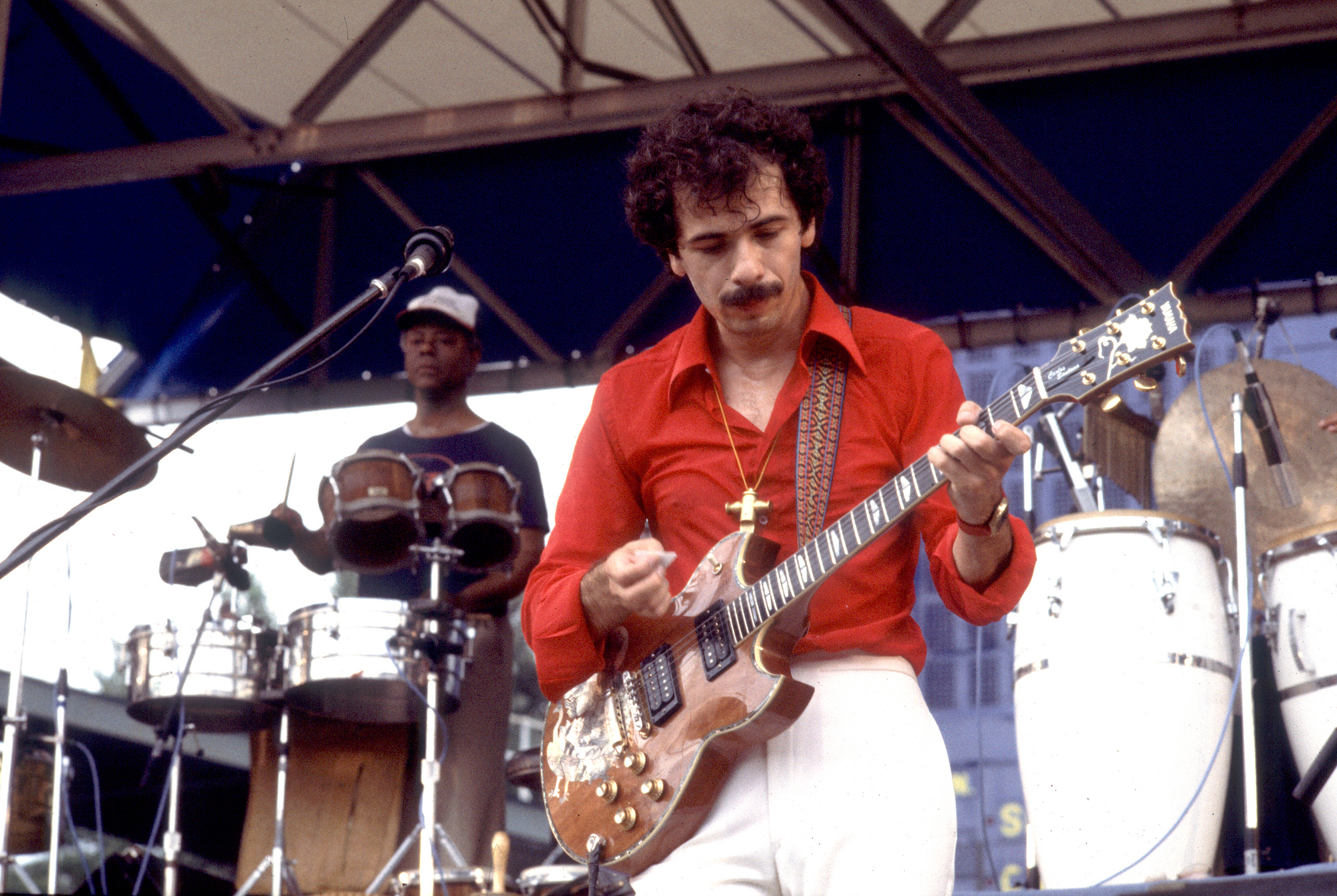

There are varying degrees of guitar hero, but Carlos Santana is a name you’d expect to find near the top of any list. Like Jimi Hendrix, Brian May or Slash, Santana has transcended guitar music and permeated his way into popular culture, immortalizing his name into legend on every corner of the globe.

Of course, he’s a tremendous player, but it goes way beyond that; he’s a highly prolific composer and collaborator, the type of musician who can thrive in just about any musical environment, drawing from an impressively wide pool of influences to make his guitar speak to any kind of audience or listener.

His latest album, Sentient, serves as yet another reminder of these universal talents. It consists of 11 tracks, three of which were unreleased until now, and the rest reimagining some of his most famous partnerships over a storied career, from a moving live version of Michael Jackson’s Stranger in Moscow to classic cuts alongside Miles Davis and Smokey Robinson.

It’s an impressive body of work that captures the breadth of his sound and imagination while taking the listener on an unforgettable journey that defies all notions of boundary or genre. And, as the chart-topping veteran explains to GW, it’s mainly because his approach to music is a profoundly holistic one.

You’re one of the most prominent faces for PRS, but you’ve played all kinds of guitars throughout the years.

“Guitars are like crayons to me. Life is the canvas, and guitars are the colors you use to express your soul, your spirit, your heart, your passion and emotions. Those are the ingredients to create beauty, and guitars are the tools.”

How many guitars do you own these days?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I don’t know, but probably not more than 100 and not fewer than 75. I guess the Fender Strats and Gibson Les Pauls would be the oldest models in my collection. I’ve got Strats from 1954; some of my Les Pauls go all the way back to 1959.”

Paul Reed Smith has mastered creating an instrument that behaves. No matter what the weather is like, it will stay in tune and always give you that great tone

You even had a Yamaha signature model in the ’80s.

“That’s right. I had a good time with Yamaha. I learned from each one of the guitar companies. They all have their own sound, texture and feel. But I always go back to my PRS models.

“Paul Reed Smith has mastered creating an instrument that behaves. No matter what the weather is like, it will stay in tune and always give you that great tone. I’m very grateful to Paul. He came up with his own vision to create a different tone and feel.

“I’m grateful he did that because his designs suited my personality when it came to self-expression. We’ve had a relationship since the late ’70s. He convinced me to come on board. Back then, there were only three companies I knew of – Gibson, Fender and Gretsch. There were others, but those three were the main ones.”

The PRS signature guitar you call “Salmon” is the guitar you’re most associated with lately. What makes it so special?

“I also think of it as my Supernatural guitar, because that’s what I used for 99 percent of that album [1999's Supernatural]. As for what’s special about it, I think it’s the most fluid. It’s the easiest instrument for me to materialize my inner-vision, thoughts and emotions. There’s not much struggle translating myself onto that guitar. But sometimes that struggle is nice, you know?

“Some people struggle with playing Stratocasters. It’s not easy to play a Strat and get really nice tones without pedals, because some people use pedals for extra sustain. But when you play loud enough like Jimi Hendrix going straight into Marshall stacks, they can become a whole other canvas. That’s why players like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Buddy Guy stuck with Stratocasters.”

PRS has continued to evolve through the years with models like the Silver Sky. Have you ever tried one?

“A bit here and there. I thought they were pretty close to the original design it had been clearly inspired by.”

The company’s SE models are also pretty well known for being some of the best guitars you can find for that kind of money.

“That’s right! From guitars to food or whatever, there are two words that are important for any business – impeccable integrity. When people put love and attention into what they make, it stands out.

“When my guitars arrive from Paul Reed Smith, they are always perfectly in tune. I’m not making it up! They come to me set up perfectly because somebody at the factory is doing that final check. A lot of companies don’t do that.”

You play PRS single-cut models, too. What kind of situations call for that over a double-cut?

It’s like wine. You’ve got choices like burgundy, merlot and cabernet sauvignon. The singlecut is more like a merlot, it’s a more robust sound

“It’s like wine. You’ve got choices like burgundy, merlot and cabernet sauvignon. The singlecut is more like a merlot, it’s a more robust sound. When you play a double-cut, the sound changes dramatically and you get more treble. So in situations where I want more of a rounder sound, I will go for the single-cut. Both have their uses for different sounds and songs.”

On your new retrospective album, you turned your guitar into a voice for an instrumental version of Michael Jackson’s Stranger in Moscow. Not many players can make their instruments talk like that.

“There are components to articulating. It’s a bit like how a chef thinks about ingredients, from flavors to nutrients. To cook a delicious meal, you need more than salt and pepper. Nothing is closer to the heart than the voice. To make a guitar speak to people, it’s more than just volume and control.

“You need to put your soul into each note; when you do that, it changes the sound. There are a lot of people who play music that’s more mental, which has a different type of feel. It’s okay for certain things, but I prefer the sound of someone playing from their heart because of players like Wes Montgomery and Otis Rush. They made you feel what you hear.”

Which singers helped you most with your phrasing?

A good guitar solo should sound like an orgasm. I can hear it in Eddie Van Halen’s playing, and the same goes for Jimi Hendrix. I live for the juicy notes

“If I sang, I’d want to sound like Marvin Gaye. If I were female, I’d want to sound like Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston or Billie Holiday. That’s what I’m thinking of when I play guitar – how to articulate.

“I’ve spent a lot of time taking my fingers for a walk with Smokey Robinson, so when I play my guitar, I become the voice through my fingers on the fretboard. It’s the same way I approached Stranger in Moscow. I had to morph myself and get into a character, almost like an actor.

“When you see Robert De Niro on a talk show and he’s not in character, sometimes he can be a little boring. But when he turns into the guy from Heat, Taxi Driver or The Godfather, he’s incredible. It’s a frame of mind. When I’m playing Stranger in Moscow, you’re hearing a different Carlos, because I’m thinking of Michael Jackson and phrasing everything differently – even if it’s still got my own fingerprint.”

On a technical level, what were you doing to sound like the original vocal?

“I chose to play more relaxed and behind the beat, choosing my notes carefully. It’s like putting your fingers in water and sprinkling someone’s face with water, or if you take a spoon to grapefruit and it squirts.

“Those are the good notes. A lot of people don’t know how to squirt their best notes! I learned this stuff from Buddy Guy, B.B. King, Albert King and Freddie King. If you don’t know how to squirt, everything is contained, and it can get boring after a while.

“I like being squirted in the face by music because it makes me feel alive. The goal of any guitar player, whatever the style may be – from funk and flamenco to heavy metal – is to make the listener feel alive. A good guitar solo should sound like an orgasm. I can hear it in Eddie Van Halen’s playing, and the same goes for Jimi Hendrix. I live for the juicy notes.”

There’s almost a Jeff Beck approach to your improvisation on that track. You knew each other and famously played together on The Nagano Sessions [with Steve Lukather] in 1986. What do you remember most about Jeff?

“Jeff Beck took guitar way beyond. His approach was like letting the hamster out of the cage. I was a big fan of Jeff from the second I heard him play. What I loved most was his imagination and passion. He was a very untraditional player, even though he had learned the traditional approach to blues to start with.

“I remember hearing Truth [Beck's first solo album from 1968] a long time ago and loving it, but I think the first song I heard by him was Over Under Sideways Down by the Yardbirds. He had this fuzz sound that was very special. You could also tell he’d been listening to people like Ravi Shankar or Ali Akbar Khan.

“He was a multi-dimensional player in that sense, the opposite of a one-trick pony. He learned from Roy Buchanan and Buddy Guy – I mean, we all took a lot from Buddy – because he put the turbo inside the blues. Like Jeff, I learned how to take a deep breath and trust my fingers almost like a child going down a water slide.”

Is it because in situations like that, it’s more about heart and soul than technicality?

“Anybody can practice scales up and down. But there’s something about coming down a water slide. You don’t know how you’re going to land; it might be on your head or on your feet.

“That’s what happens when you deviate from the melody. John Coltrane, Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter taught me a lot. It’s the art of improvisation, entering the unknown. People would ask Wayne how he practices, and he’d tell them, ‘We don’t know what we are going to play; how do you practice the unknown?’

“I learned improvisation from Coltrane. I learned cosmic music from Sun Ra. I learned down-to-earth music from the Grateful Dead because they were heavily immersed in the folk and bluegrass worlds. And don’t dismiss the guitar playing of Bob Dylan. He played a lot of great guitar, which worked beautifully with his vocals. I’ve learned from many musicians, especially the incredible women I mentioned earlier.”

Playing along to soul singers is something nearly every guitar player could learn something from.

“I don’t care who you are, whether you are Al Di Meola or not, I’d recommend this to any guitar player. If you spend even one day learning how to play and phrase like those lady soul singers, you will become a better musician. This is the truth. This is genuinely the most important part of the interview – right now. The only thing people will remember about your music is how you made them feel.

“They are not going to remember all the fast scales and ‘Look at what I can do!’ moments. But they will remember those three notes that made the hairs stand on the back of the neck and tears come out of their eyes, even if they don’t know why. That’s a whole other element, one I call spirit. Some people don’t know how to play with spirit, heart and soul. Those are three very important ingredients.”

Music isn’t a sport at the end of the day – especially for the listener.

“If you just practice all day and night going really fast, after a while, it’s a bit like going to the gym and seeing somebody flexing their muscles. Big deal. So what? Playing with spirit is like giving someone a hug that lasts for infinity. Time stops.”

Are there any songs that you think demonstrates this best?

“There’s a note Jimi Hendrix plays in All Along the Watchtower that makes you feel like you are entering eternity. It’s like being from Kansas and having only seen the Pacific Ocean on a postcard, then going to Hawaii and putting your feet in the water. That’s when you understand the totality and absoluteness of an ocean. A lot of musicians don’t understand how to play like that, but Chick Corea can.

“You have to learn how to dive into infinity through one note. It’s like learning how to French kiss correctly – to be fully alive with all your senses but no guilt, shame or embarrassment. Take the inhibitions and all that stuff out. You will see how beautiful it is to interact so intimately. That’s what a guitar player is. The guitar is a very naked and sensuous instrument. That’s just the way it is.”

The other Michael Jackson track on the album, Whatever Happens, has some harmonic minor lines, but on nylon acoustic. Where’d you learn to use that sound?

They also said I was using tonic scales, but the only tonic I knew was in gin and tonic

“I got a lot of it from my father because he played violin. It’s funny; when I started, people would say I was using a Dorian scale. But the only Dorian I knew was a girl who went to my junior high school. She invited me to go over to her house when her mom was working. I had a good time with Dorian.

“They also said I was using tonic scales, but the only tonic I knew was in gin and tonic. I don’t know, nor do I want to know, about scales because that will get in my way. I would rather feel like a blind man touching someone’s face. They are memorizing something in a completely different way to how someone else would see it.

“I’m not saying ignorance is bliss; I’m saying that if you learn everything, you can take some of the magic away. Don’t lose the magic of self-discovery. There’s something so beautiful about purity and innocence. Again, it’s like that first kiss.”

The Smokey Robinson track, Please Don’t Take Your Love, has a distinct, lively blues tone. What were you using?

“That sound is a combination of three things. The guitar was a really old white Stratocaster going straight into a Dumble amplifier that was lent to me by Alexander Dumble. The tone of that Strat with the Dumble is something magical.

“You stop playing notes, sounds and vibrations, and it all becomes a living sensation. How many players can say they play with a living sensation? Manitas De Plata, Paco De Lucía, John McLaughlin and Sonny Sharrock. The main ingredients for me are spirituality and sensuality. Without those two things, I wouldn’t play guitar like this. I wouldn’t want to be on this planet.”

Get On is an interesting piece of music. Do you play differently knowing someone like Miles Davis is on the same track?

‘I’m almost 80. I’ve learned how to diversify my portfolio and my Rolodex of expression, tones and vibration. When I first heard this song with Miles, I had to trust that I knew enough about what he was doing.

“Certain music comes from Africa, and that went on to influence stuff played by Cubans and Puerto Ricans, all this sensual music like guahira, bolero, charanga. If you listen to the African band Kékélé, you will hear a lot of Santana in there. I have to give credit to the musicians because they knew how to make music feel like it’s alive. It’s not just notes and clever inversions. I always go back to something physical.

“You have to make people feel. They can’t take it or leave it. The song has to speak to them. They will stop all conversations because they are enthralled and captivated. The sound is making love to them. And it takes trust. If there’s no trust, you won’t get the goods. With music, you gotta give the goods, man. Otherwise it’s just too clever and intellectual, and that stuff is boring.”

You’ve said Stevie Ray Vaughan once came to you in a dream and told you to use his Dumble Steel String Singer amp for a performance at Madison Square Garden. Not many people can say that.

I get visitations from Miles Davis sometimes, as well as B.B. King

“I call them visitations. I get visitations from Miles Davis sometimes, as well as B.B. King. You don’t have to be dead to visit me. Sometimes a dream is not a dream; someone has come back to communicate with you.

“I had a dream about Miles where I went to his concert and someone said, ‘Miles knows you are here and wants to see you in his dressing room.’ He asked how I was doing and started writing on a bit of paper, which he then gave to me. And just as I was about to read it, I woke up. I have to analyze what he was trying to tell me.

“It’s like that with Stevie Ray and Jaco Pastorius. I feel very honored that these people come to me. Sometimes I feel like I’m like [John F. Kennedy International Airport] and all these musicians are landing on me and sharing things. I have to figure out what it all means.”

What exactly did Stevie tell you?

“With Stevie, he was saying, ‘Carlos, where I am, I don’t have any fingers; I am only spirit.’ He missed putting his fingers on a guitar and making the speakers push air. He told me to call his brother Jimmie [Vaughan] and ask him to lend me his amp, the #007 Dumble, and then play it with a Strat so he could feel it through me. You know that Ghost movie with Whoopi Goldberg? There’s a part where a ghost comes into her body so he can feel. That’s what Stevie was doing.

"He wanted to utilize my body and hands because he missed playing guitar. Jimmie wasn’t sure at first. Fortunately, Stevie’s tech, René Martinez, had the same dream and called Jimmie, which is how we convinced him to lend me the amplifier. The last person to borrow it was John Mayer. Let’s just say Jimmie doesn’t loan that thing out very easily.”

Rightly so. For those of us waiting in vain for Jimmie Vaughan to give us the green light on the Dumble, how would you describe the sound of that amp?

“It sounded like everything I love about Peter Green when he played a certain kind of heavenly blues. My mom once asked me, ‘Mijo, do you like Whitney Houston?’ and I said ‘of course.’ She then told me that when Whitney sang, her voice would become a legion of angels. I think my mom knew what she was talking about.

Those Paul Butterfield Blues Band albums, like the [self-titled] debut and East-West, are incredible... Michael Bloomfield was a hero beyond heroes to me

“Sometimes when you play, you channel things. One person I haven’t mentioned too much is Michael Bloomfield. I miss him a lot. He was a great player who knew how to tap into things. Those Paul Butterfield Blues Band albums, like the [self-titled] debut and East-West, are incredible, with songs like Born in Chicago. And the stuff he played with Bob Dylan, forget about it. Michael Bloomfield was a hero beyond heroes to me.

“But the guy who got me out of all that stuff was [Hungarian jazz, pop and rock guitarist] Gábor Szabó. The way he could play ballads was amazing. Listen to his album Spellbinder [1966] and you will hear a lot of Santana in there. Anyone reading this should listen to Hungarian gypsy music. There is nothing more romantic than hearing that stuff. It really pulled me out of the blues, which is something we all need from time to time.”

- Sentient is out now via Candid.

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Santana - Full Concert [HD] | Live at North Sea Jazz Festival 2004 - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/UOwvmgjbwDo/maxresdefault.jpg)