“Every time I picked up a guitar I got the horrors”: Radiohead were the world's most talked-about guitar band. Then they burned the rulebook, and made the instrument sound like no-one else had before

Released 25 years ago, Kid A subverted all of the lofty expectations that had been placed on the band, and cemented their status as one of popular music's leading creative lights

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“Every time I picked up a guitar I got the horrors.”

Speaking to Q in a 2000 interview, Radiohead’s Thom Yorke was reflecting on the Herculean task of writing the material for what would become the band’s fourth album, Kid A.

The picture of what seems like a somewhat over-the-top reaction to your run-of-the-mill writers block becomes a bit clearer when you take into account that Yorke was attempting to follow up OK Computer, the landmark 1997 album that catapulted Radiohead from alt-rock outcasts with a fairly sizable following to true rock royalty – uniting in euphoric praise all but a few scattered dissenters in the music journalism intelligentsia, and raising the eyebrows of even those who didn’t really like what they heard.

It came at a curious moment in rock guitar. The garage-through-a-broken-mirror riffs of the grunge tidal wave had well and truly washed away – the genre’s biggest bands having mostly fallen apart due to tragedy or stasis – but the feral aggression of down-tuned nu-metal was still just out of sight, gathering strength for its JNCO jean-powered offensive.

It was into that vacuum that the world received OK Computer, a collection of jittery and jagged rock anthems (and they were anthems) that expressed uneasiness and disaffection with what at the time made many optimistic and hopeful – the embrace (by choice or by force) of the cutthroat capitalist Washington Consensus ideology around much of the world, and, in particular, the seismic advances of technology.

There was little reference point for it, musically. It featured the birth of a (very) reluctant new guitar hero in Jonny Greenwood, who ripped sounds out of his Telecaster Plus that were not of this Earth.

Paranoid Android, Subterranean Homesick Alien – he graced the sci-fi names of the songs with tones to match. Not one, but two, disconcerting solos in the former – the first opening with a frenzy of gonzo tremolo picking, the wayward stabs of the latter sometimes sucked into a black hole by the envelope filter of Greenwood’s Mutronics Mutator rack unit.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Aiming for the cosmos on Alien while Radiohead’s ever-steady third guitarist, Ed O’ Brien, kept a foot on this planet with haunting arpeggios, Greenwood used the ever-versatile DigiTech Whammy to beam three-note statements into interstellar space.

OK Computer was immediately recognized as singular. “Saviors” of rock, of the guitar – got thrown around a lot. A 1997 Guitar World piece on the band noted frequent comparisons of the album to the work – in scope and significance if not subject matter – of Pink Floyd and U2.

Moving into the 21st century, an essay in no less than the United States Library of Congress equates OK Computer to the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

During the presidency of George W. Bush, Coldplay’s Chris Martin went so far as to suggest that the Bush administration’s policies might change for the better if then-Vice President Dick Cheney gave the album a spin.

“It changed my life, so why wouldn't it change his?”

How do you follow something like that up?

Well, O’Brien explained in a 2017 interview with Total Guitar, the answer was “‘Bring synths in, throw our tools away.’”

Mind you, this wasn’t a unanimous decision.

Ever the band’s liaison to the world of Guitar Rock™️, O’Brien felt that if Radiohead were indeed seen as the genre’s foremost creative talents, why not double down?

Coldplay were channeling the band’s soaring melodies and enormous choruses into sing-along giga-hits, while millions of those attracted to the band’s heavier, dystopian side were finding kinship in the work of Muse. Show the world who the originals are, eh?

I'd completely had it with melody. I just wanted rhythm. All melodies to me were pure embarrassment

Thom Yorke

For Yorke, who was feeling the aforementioned pressure of writing, as O’Brien put it in a 2000 interview with Total Guitar, “three-minute guitar songs,” the doubling-down idea was a non-starter.

“I'd completely had it with melody,” Yorke told Q in 2000. “I just wanted rhythm. All melodies to me were pure embarrassment.”

Hugely inspired by the angular beats and expansive ambient soundscapes of electronic music boundary-pushers like Boards of Canada and Aphex Twin, Yorke wanted to build songs up from drum machines and textures, not riffs, melodies, or hooks.

Though he had no attachment to his status as a nouveau guitar hero (he told Rolling Stone in 2017 that he’s “always hated guitar solos”) even Greenwood was reportedly thrown by just how left-field Yorke’s newfound approach was, never mind the feelings of the band’s bassist – Greenwood’s older brother, Colin – drummer Phil Selway, and, of course, O’Brien.

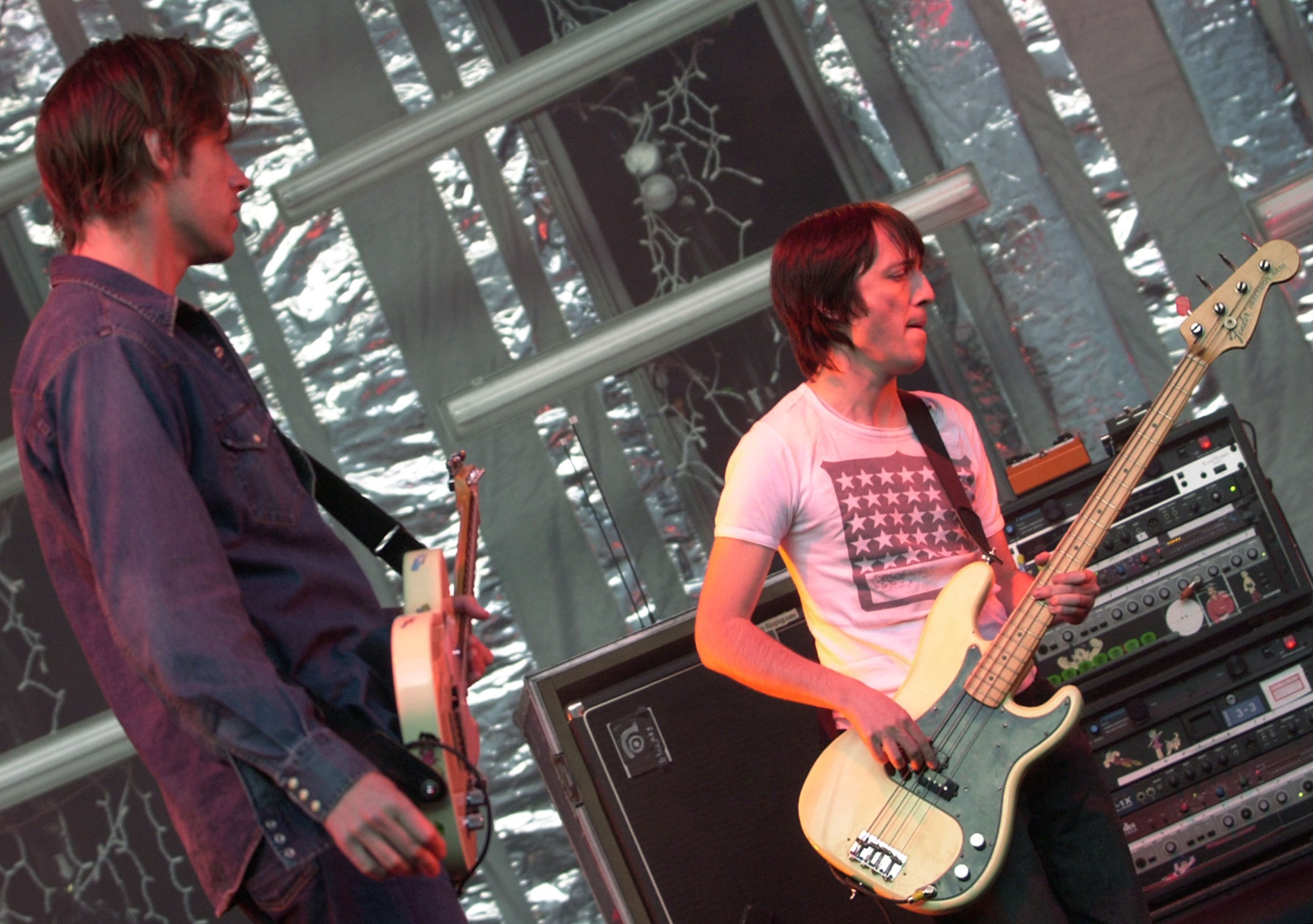

The subsequent recording process was lengthy, and beset with teething problems, as the band tried to start from square one. Songs were nebulous, with the band exchanging roles ad hoc – Jonny Greenwood responsible for beats on one song, keys on another; Yorke on bass here with Colin Greenwood on keys there. Even Selway picked up the guitar on occasion.

Of an August 1999 rehearsal featuring much of the band’s new material, O’Brien wrote – in his revealing online diary documenting the Kid A recording process – “[I] think that these rehearsals will be viewed in hindsight as where we turned a corner (or hope so).

“Obviously, working on the songs and playing again has helped, but just as importantly we have been forced to confront certain things – like what the fuck are we doing exactly? – how do we set up the next bit of recording so that we don’t start 20-odd songs and not finish one of them?”

Speaking to Total Guitar in 2000, Selway described the band’s six-string division of labor up to that point thus: “In the past, Ed would make these marvelous sounds, Jonny would play the angular lead parts, and Thom would be playing the driven parts, but that's over now.”

As a young guitarist, I was always drawn to sounds that didn’t sound like the guitar

Ed O'Brien

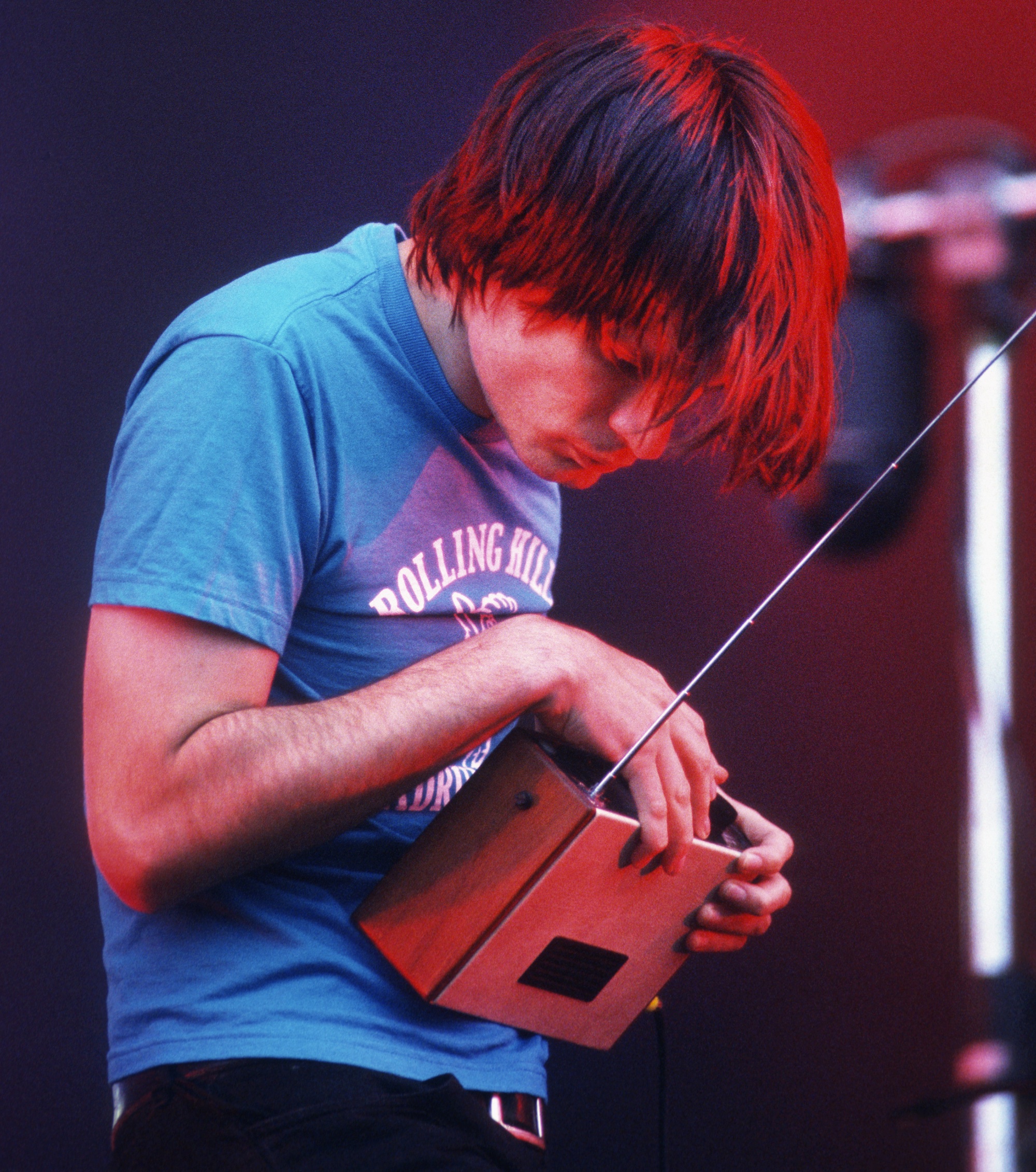

Jonny Greenwood, though still picking up the guitar from time to time, ventured off into instrumental lands unknown. In particular, he developed a fondness for the Ondes Martenot, an obscure early electronic instrument not too distant from a theremin – all eeriness and sustained whirring.

O’Brien, in turn, realized that – aside from working more on keyboards – he had to take his playing’s more textural side one giant leap further; and to do so, he too needed some new kit.

An October 1999 diary entry, for instance, reveals a Roland guitar synth to be his “new toy.” But he also wanted something that could add bang-for-buck value to his limited-by-necessity playing, and contribute prolonged textures, like those the younger Greenwood was discovering in his Martenot and innumerable other analog synths.

Enter the Sustainer pickup.

“The first time I heard the Sustainer thing was on Michael Brook’s Infinite Sustain guitar,” O'Brien told Total Guitar in 2017. “He gave one to the Edge on The Joshua Tree; that’s the sound on With Or Without You, that high-pitched thing. So as a young guitarist I was always drawn to sounds that didn’t sound like the guitar.”

“When we threw guitars out, I got in contact with Michael Brook and had a great conversation when we were in the studio. And he directed me towards Fernandes, who had the Sustainer,” he recounted later in the interview. “I had a Clapton Strat from the mid-’90s, and we put the Sustainer unit in there, and that’s when we started using it, around 2000.”

Just as this was occurring, the guitarist was contrasting the vintage, analog tools strewn about the studio by eagerly adding new tech to his pedalboard.

“We took my Clapton Strat with Lace Sensor pickups that I loved, fitted a Fernandes Sustainer unit in it, and at the same time it was the birth of all these new looping pedals,” he told Total Guitar. “The Akai HeadRush had come out and the Line 6 DL4. The combination of the two was… bonkers!”

Slowly but surely, the stubborn, amorphous songs began to take shape – some picking up more conventional arrangements on the way, others ditching them.

One of the first to solidify was Optimistic. Having begun life on Yorke’s 505, it quickly evolved into one of the album’s few full-band, guitar-heavy workouts.

“Optimistic is possibly my favorite band song that is played together live in a room,” O'Brien wrote online in October 1999. “Sounds fucking great.”

The end result was a rare display of muscle, a thundering, hard-riffing statement that kept with the album’s obscure atmosphere, but was dressed in enough conventional rock-with-a-capital-R clothing to, say, soundtrack a Top Gear montage of Ayrton Senna whipping his Formula 1 car around the streets of Monte Carlo.

Charles Mingus-style free jazz freakout brass was added to The National Anthem, a freight train of rhythm section drive led by one of the great rock basslines of the 21st century – a must to get under your fingers, especially if you’ve got some dirt at hand on your pedalboard or amp.

Those songs aside, though, the bring-the-guitars-off-the-stands moments were thin on the ground as things finally finished up.

There’s a climactic outburst of built-up riffing following the third verse in Morning Bell, the dazed triplets of In Limbo, and the dreamy acoustic strums of How to Disappear Completely – all mesmerizing. But it's always when the band steps off into the synthesizer and effects deep end – truly burying the instruments that had made them the belles of the ball and making them unrecognizable – that the album becomes a world unto itself.

There’s Everything in its Right Place, essentially a drone with looping wizardry and one of Yorke’s most expressive vocal performances; the ever-underrated title track, a beautiful and disquieting lullaby; Treefingers, a pure formless soundscape that wouldn’t sound out of place on one of Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works albums... guitars are barely discernible, texture only, if that.

Idioteque, arguably the album’s (if not the band’s) crowning achievement and thesis statement, was built not from a riff or chords but an otherworldly four-note synthesizer hook, poached – with permission – from composer Paul Lansky's early electronic composition, Mild und leise.

“Knives Out is the only song on the new record which is basically three guitars, bass, drums, and vocals,” O'Brien explained to Total Guitar in the months before the album's release.

“The only one, and when we finished it we worked out that we'd spent 373 days on it. And when you hear this song, you'll go ‘Why did you take so long to do something like that?’”

When Kid A was released on October 2, 2000, though, Knives Out was nowhere to be found. Eager readers would have to wait for the release of Kid A’s sibling, Amnesiac, the following year, to hear it.

Radiohead had indeed thrown away their tools, and the pedestal that so many had put them on. They were nothing close to the first band to blend guitars and electronic instruments, but the way they did it – turning the former into tools that generated quiet sound manipulation and atmosphere more than melody and rhythm – re-defined what “rock” and even “alt-rock” meant to people.

When all was said and done, listener confusion meant little – the album became the band's first chart-topper in the United States. Upon release, it, unsurprisingly, met with a far more polarized critical reception than its predecessor, but those who praised it often did so in euphoric terms.

Austere and inscrutable, the album was a violent reaction to the messianic expectations that had been placed upon the band, and couldn't have stood out more in the environs of rock's other chart-toppers; aggro blasts of angst that told listeners to, among other things, “break stuff.”

Even 25 years on, Kid A still sounds like nothing else – alien, you might say.

Jackson is an Associate Editor at GuitarWorld.com. He’s been writing and editing stories about new gear, technique and guitar-driven music both old and new since 2014, and has also written extensively on the same topics for Guitar Player. Elsewhere, his album reviews and essays have appeared in Louder and Unrecorded. Though open to music of all kinds, his greatest love has always been indie, and everything that falls under its massive umbrella. To that end, you can find him on Twitter crowing about whatever great new guitar band you need to drop everything to hear right now.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.