“As soon as they started to jam, all three felt the magic. They instinctively knew they were on to something”: Their first single was so bad, the label pulled 10,000 copies. Yet they went on to be one of the most influential supergroups in music history

60 years ago, Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker put together Cream. This is the story of the early years of the power trio that changed the face of popular music, and elevated Clapton to God-like status

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By the mid-’60s, as jazz bands slowly faded from the front pages of the music press, they were gradually replaced with rhythm and blues bands.

One such band featured Graham Bond, a complicated figure and musical innovator who would go on to inadvertently pave the way for many bands over the next few decades.

We go back to the beginning – including the bust-ups and band-member swaps – to detail the rise of one of Britain’s most revered supergroups.

Article continues belowThe name’s Bond

Bond started his career in jazz, playing with Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated. He left the outfit in 1962 and formed the Graham Bond Quartet with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce, both from Alexis’s band, along with guitarist John McLaughlin.

By the mid-’60s Bond decided to move toward the more-successful blues scene, keeping members of the quartet together and adding Dick Heckstall-Smith to the line-up. Dick replaced Bond on sax as Bond switched over to Hammond organ and vocals. As the Graham Bond Organisation, they very quickly established themselves, and released their first album in February 1965.

By this time, drugs had become an issue for the band, and Bond, in particular, found it difficult to deal with the associated problems. On top of that there were a lot of arguments between Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, sometimes getting violent.

A stressed Bond decided to hand over leadership to Ginger Baker, who saw this as a perfect opportunity to fire Jack Bruce. The band limped on as a three-piece, but the magic had gone. Although Ginger stayed in the band for a time, he decided to quit when Bond’s increased drug habits made him too unreliable.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

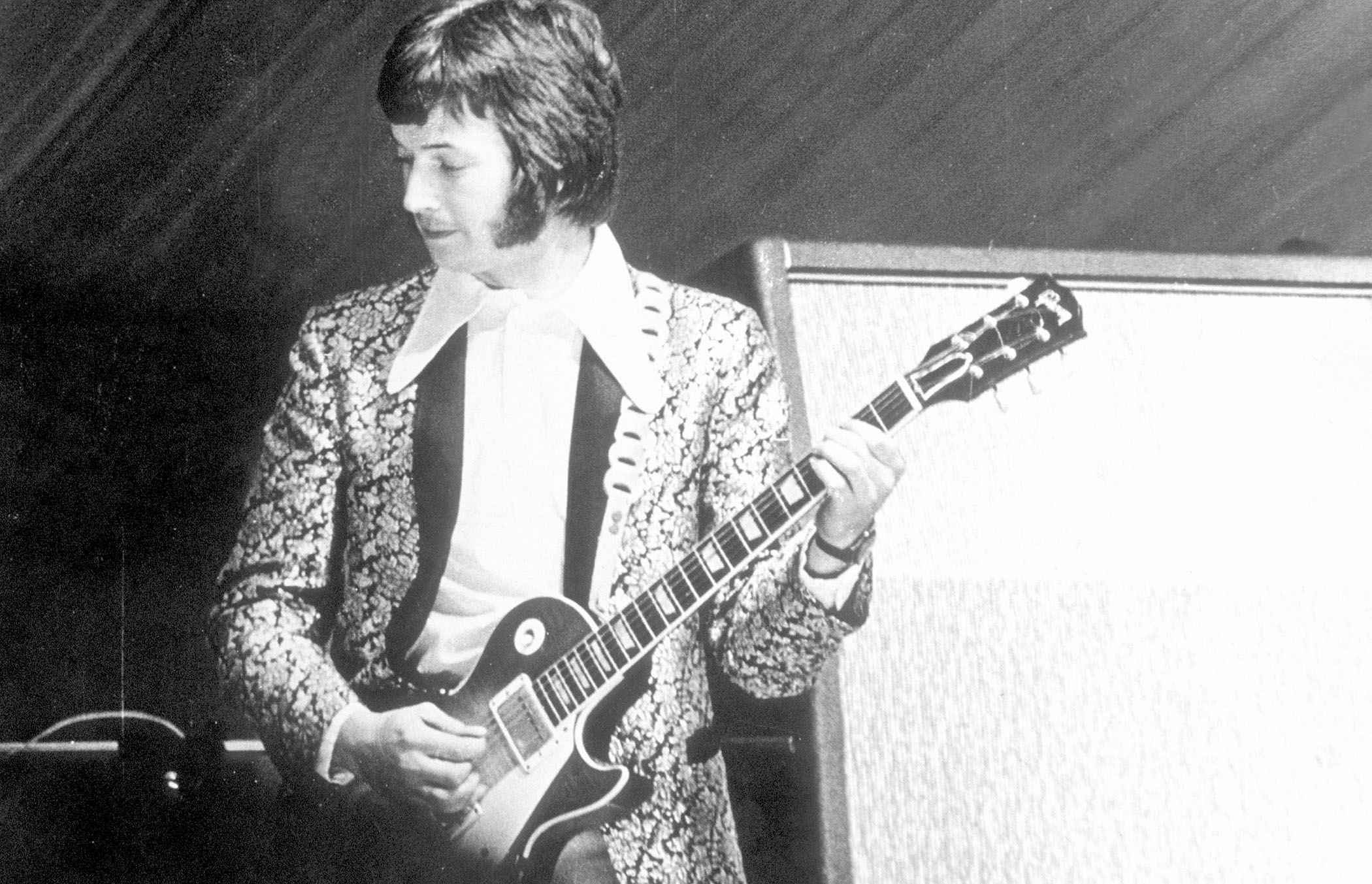

Ginger was now at a loose end and was keen to form a band, and set about finding like-minded musicians. He was already familiar with Eric Clapton and his guitar playing when they frequently met on the London club scene, and so he wanted to approach him first. It’s worth knowing that at that time graffiti would often be spotted in London proclaiming that ‘Clapton is God’, such was the strength of his loyal following.

Part of the reason for Eric’s popularity was the tone he achieved with his beloved 1959 sunburst Gibson Les Paul played through a JTM45 Marshall amp.

He had bought the guitar from the Lew Davis shop in London’s Charing Cross Road in 1965 with money he earned playing with John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers from 1965 to 1966. It was the album cover of Freddie King’s Let’s Hide Away and Dance Away that influenced him to buy the guitar, even though Freddie was, in fact, holding a Goldtop.

A New Trio

Ginger went to see The Bluesbreakers at a gig at the Town Hall in Oxford on 13 May 1966 and asked if it would be okay to have a jam. Ginger and Eric had an immediate musical chemistry and got on well, too. After the show, Ginger gave Eric a lift home and asked him if he would be interested in joining the new band he was forming.

By this point, Eric was tiring of copying his blues heroes and he, too, was looking for new opportunities. It didn’t take long to make a decision, but his only condition was that Jack Bruce would have to be in the band. Eric had no knowledge of the past tensions between Jack and Ginger.

Ginger was taken aback but highly respected Jack’s musicianship – he could see the potential for the three members coming together as a band. After some persuading from his wife, Ginger went to visit Jack to find out if he would be interested in putting the past behind them and joining the band.

At the time, Jack was under contract with the group Manfred Mann but was not happy at the pop direction they were pursuing. Jack was also familiar with Eric and his guitar playing as he was also in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers for a short period in during late 1965.

Both he and Eric enjoyed the experience of playing together, and later even recorded a few tracks for a blues compilation album, What’s Shakin’, for the Elektra label in March 1966. Jack was in and Ginger immediately suggested Robert Stigwood as their manager, having known him from his time with Graham Bond.

The three musicians wanted to be collaborative, rather than act as three soloists competing with each other. Originally, Eric Clapton had visions of being the lead singer but conceded that Jack had a far more powerful voice with a wealth of experience behind him. Eric considered the band to be ‘the top of the milk’ in terms of musicianship, and suggested it made sense to call themselves ‘The Cream’.

Initial rehearsals took place at Ginger’s ground floor maisonette in Neasden, North London, before moving to St Anne’s Brondesbury Church Hall in West Kilburn. As soon as they started to jam, all three felt the magic. They instinctively knew they were on to something.

Melody Maker’s Chris Welch was at the hall and during a break joined the band at a cafe opposite. Robert Stigwood attended the rehearsals and asked Chris if he thought they were any good.

Luckily, he said yes. Had he said he wasn’t that moved, it could have been the end of the band before they even started. However, Stigwood did have a contribution and that was the band should simply call themselves ‘Cream’.

![Cream pictured in London, 1967 [L-R]: Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/oBGRx9bwkLynGJYCvLeXJB.jpg)

A few days in, Eric’s beloved ‘Beano’ Les Paul was stolen from the rehearsal hall. His distinctive leather guitar strap with the names of his blues heroes carved on was attached to the guitar; that was also gone.

You’ve probably heard about me taking the covers off my pickups: this is something I would definitely recommend for any guitarist. The improvement, sound-wise, is unbelievable

With a view of getting the public’s help, Eric gave interviews in the music press, sharing details of the guitar as well as mentioning the carved names: Buddy Guy, Big Maceo and Otis Rush. With that information, it would be easy to detect the stolen items should anyone try to sell them.

As for the guitar, Eric described it, precisely to Record Mirror as “a Les Paul Standard, five or six years old, small and solid. It has one cutaway and is a red-gold colour with Grover machineheads. The back is very scratched and there are several cigarette burns on the front”.

It’s worth noting that toward the end of 1965, Eric had removed the metal pickup covers to reveal the bobbins: double-white at the neck, double-black at the bridge. In early 1966, he told Beat Instrumental: “You’ve probably heard about me taking the covers off my pickups: this is something I would definitely recommend for any guitarist. The improvement, sound-wise, is unbelievable.”

To this day, despite rumoured sightings on the East Coast of America, nothing ever materialised. Later, Eric confirmed this Les Paul was the best he’d ever had.

Although he also had a Gibson ES-335 from his time with The Yardbirds, he loved the sound achieved with the Les Paul. So for the first few months of Cream he borrowed a Les Paul, possibly from Keith Richards, before buying another ’Burst from Andy Summers.

To twist the knife further, his original Les Paul case was later stolen from a Cream show at Klooks Kleek. Eric surmised that the person responsible for taking his guitar had now come back for the original case.

Perhaps the most surprising piece of information was that Eric seriously considered getting a Rickenbacker shortly after the theft, as Les Paul guitars were hard to find at the time. It would seem a strange decision as the sound would have been very different from a Les Paul.

Waxing History

Stigwood set about organising press releases, tour dates and recording studio time for a single and album. The biggest issue was that Ginger and Eric were not songwriters. But Jack was a good composer and joined forces with lyricist and beat-poet Pete Brown for a selection of collaborative songs to feature on Cream’s first album. It was a mix of pop numbers with a selection of well-chosen blues covers.

They spent three days in August 1966 recording at Rayrik Sound Studios in Chalk Farm with a view to getting an all-important single in the record shops and hopefully the charts. The studio was relatively primitive and better suited to demo recordings, but during their time there they recorded four songs: Coffee Song, Beauty Queen, You Make Me Feel and Wrapping Paper.

After much deliberation they decided to release Wrapping Paper, a somewhat bland and presumably unrepresentative song with no commercial appeal. It was more a whimsical music-hall folly than a blues or pop number, at least as far as the public were concerned. Coffee Song had also been considered for release but lost out.

It was disappointing and Stigwood’s label, Reaction, pulled 10,000 copies from shops as they could not give the single away. Eric tried to explain to Record Mirror at the time: “I’m tired of being called a specialist musician. People thought Cream was going to be a blues band, but it’s not – it’s a pop group, really.”

Eric also told Melody Maker’s Chris Welch: “Most people have formed the impression of us as three solo musicians clashing with each other. We want to cancel that idea and be a group that plays together.”

Whipped Cream

Cream’s tour started with a warm-up show on 29 July 1966 at the famous Twisted Wheel in Manchester, with another set in the early hours of 30 July. The next day, they played the 6th National Jazz and Blues Festival at the Royal Windsor Racecourse in Berkshire – their official debut.

They played a 40-minute set in the pouring rain, but despite the weather, some 10,000 fans cheered the band on through the electrifying and powerful set. There were several highlights, including Ginger’s epic drum solo in Toad, which drove the crowd crazy and demanding more.

The tour carried on throughout the year around the UK, and the band often played two shows a night. Cream were not known to invite guests on stage with them, but there was one exception during a show on 1 October 1966 at the Regent Street Polytechnic in London.

Jimi Hendrix, the new kid on the block, asked if he could jam on a couple of numbers. Eric and Jimi admired each other, so although Ginger was not so keen, the band allowed the guitarist to come on.

They played a powerful version of Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor to the delight of the crowd. As word spread about the jam that evening, the glowing reputation of both Cream and Hendrix were now a done deal.

The recording sessions for Fresh Cream, the band’s debut album, were fitted in during rare days off on the tour, at Ryemuse Studios in Mayfair. I Feel Free, backed with N.S.U., was released as their second single as a taster to the album in December 1966. Completely different in feel to the first single, it screamed ‘pop’ song and went as high as No 11 in the UK charts, creating plenty of anticipation for the album.

The album cover varied with different typefaces for the UK, Europe and the US. Another change was the addition of the UK single I Feel Free to the later US release in 1967, replacing Spoonful, meanwhile Europe had the benefit of having Wrapping Paper and The Coffee Song added as a bonus.

Perhaps the most exciting release was reserved for the French market, though, where Polydor released a four-track EP containing a unique take of Cat’s Squirrel with a totally different guitar solo by Eric. Needless to say this grew to be a major collectors’ item over the years. Luckily, it is now readily available on the deluxe editions of the album at a reasonable price compared with the original EP.

In the days before social media, bands would promote their records by doing radio sessions for the BBC as well as appearing on popular youth-orientated television shows such as Ready Steady Go!. Cream’s many BBC Radio sessions sealed the deal on their popularity, and over the years their debut album has grown in stature and remains an essential album to this day.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.