“Here’s a diary entry from July 24, 1974: ‘Argument with Bill Bruford. Bill says, ‘They might as well get a session guitarist’”: The making of Red, the album that pushed King Crimson to the brink

Robert Fripp digs into his long-unopened personal diaries with Guitar World as he shares the story of the relentlessly heavy and ambitious 1974 prog classic

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

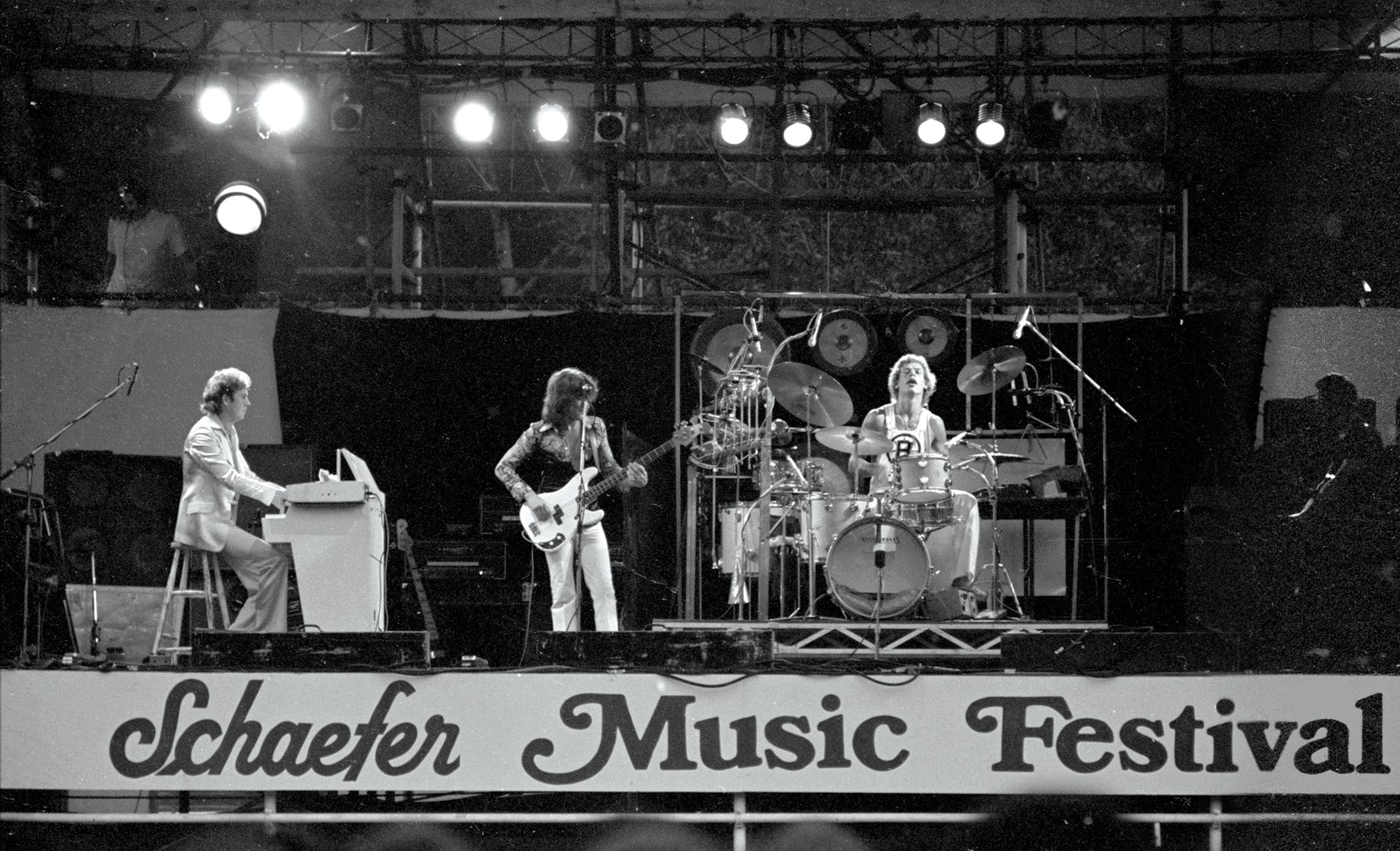

By the summer of 1974, King Crimson had reached critical mass. Albums like In the Court of the Crimson King (1969), Larks’ Tongues in Aspic (1973), and Starless and Bible Black (early 1974) had seen the venerable British band reach the apex of proto-metal-meets-fusion-meets-prog.

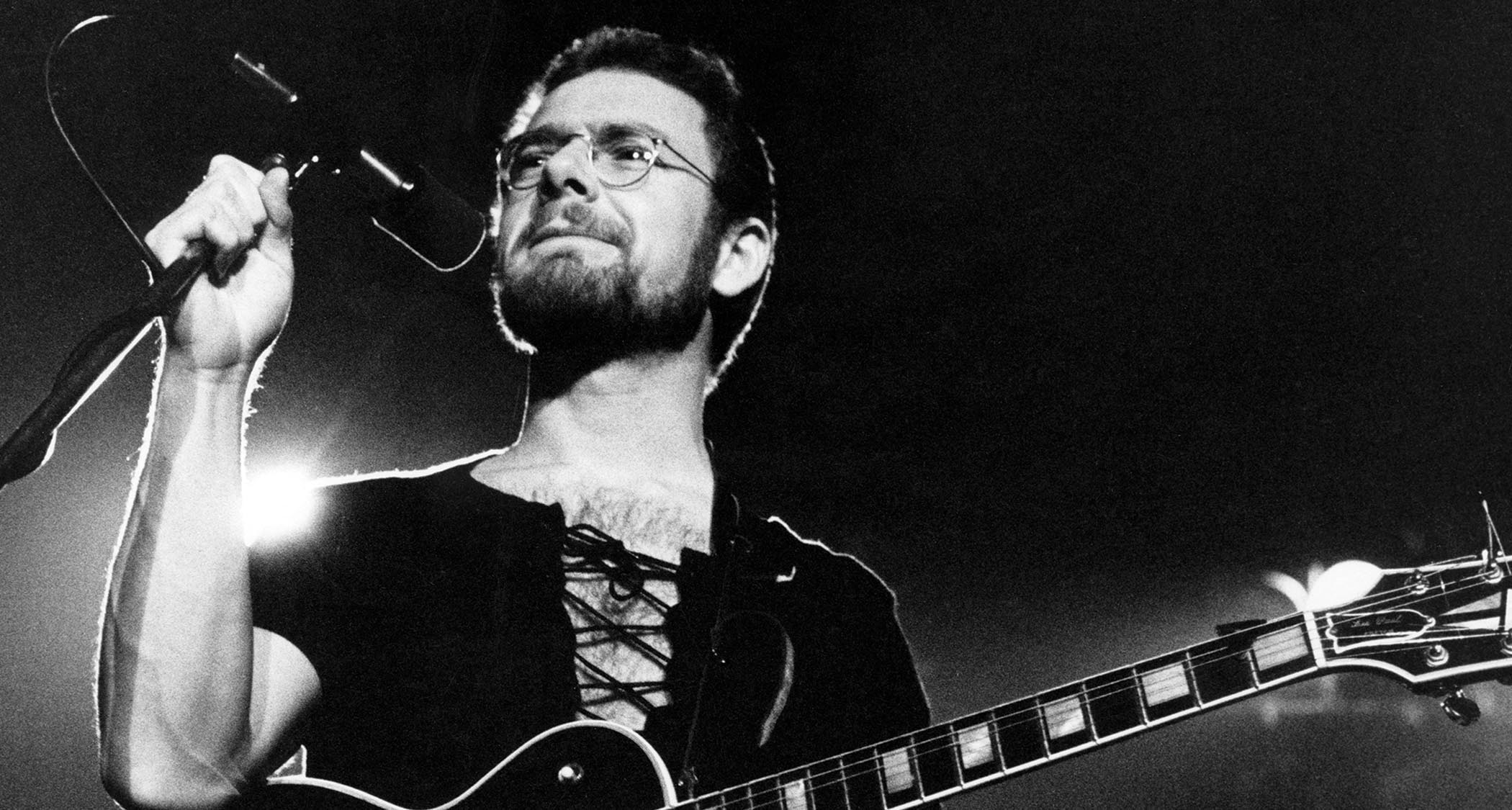

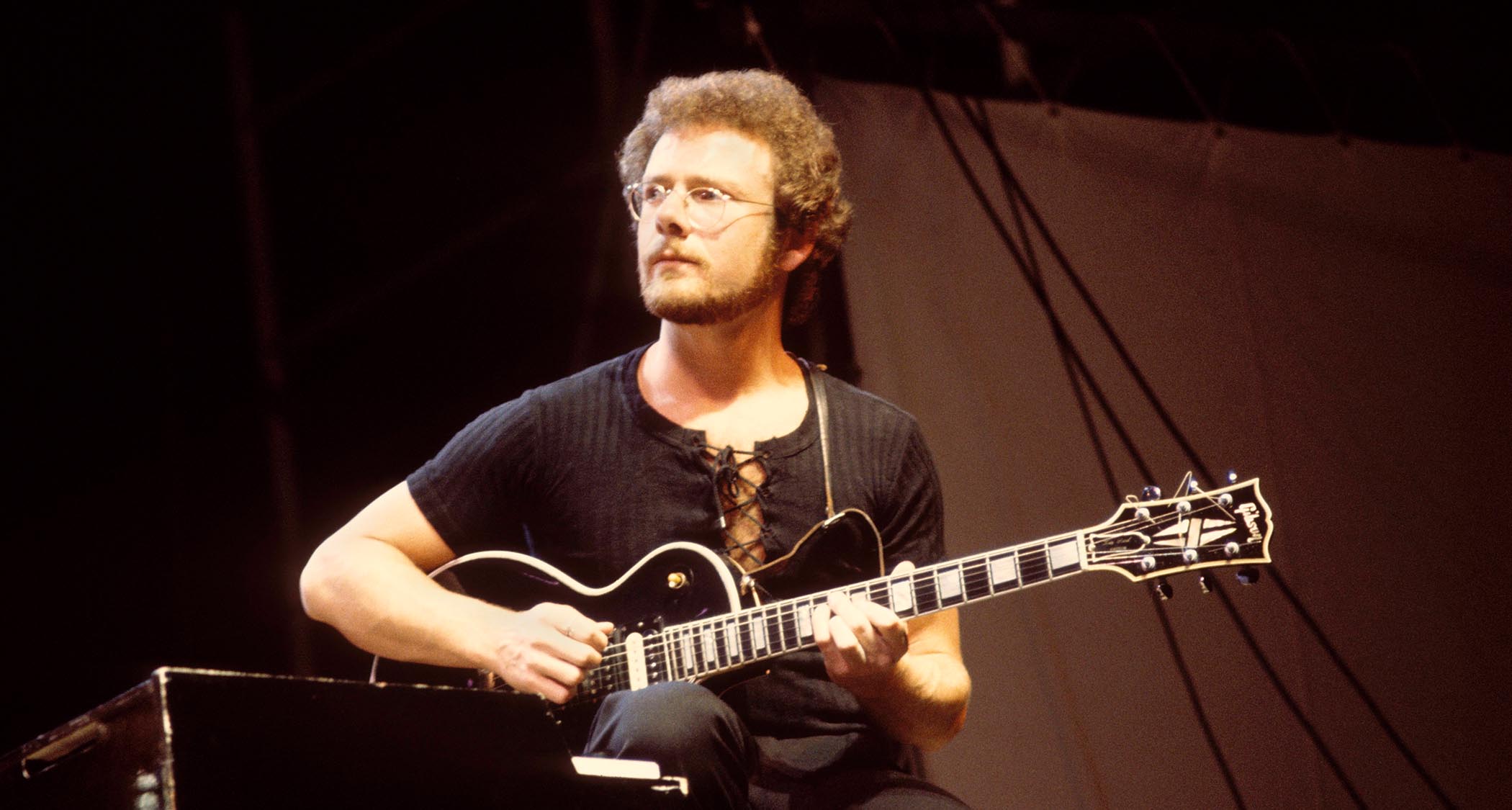

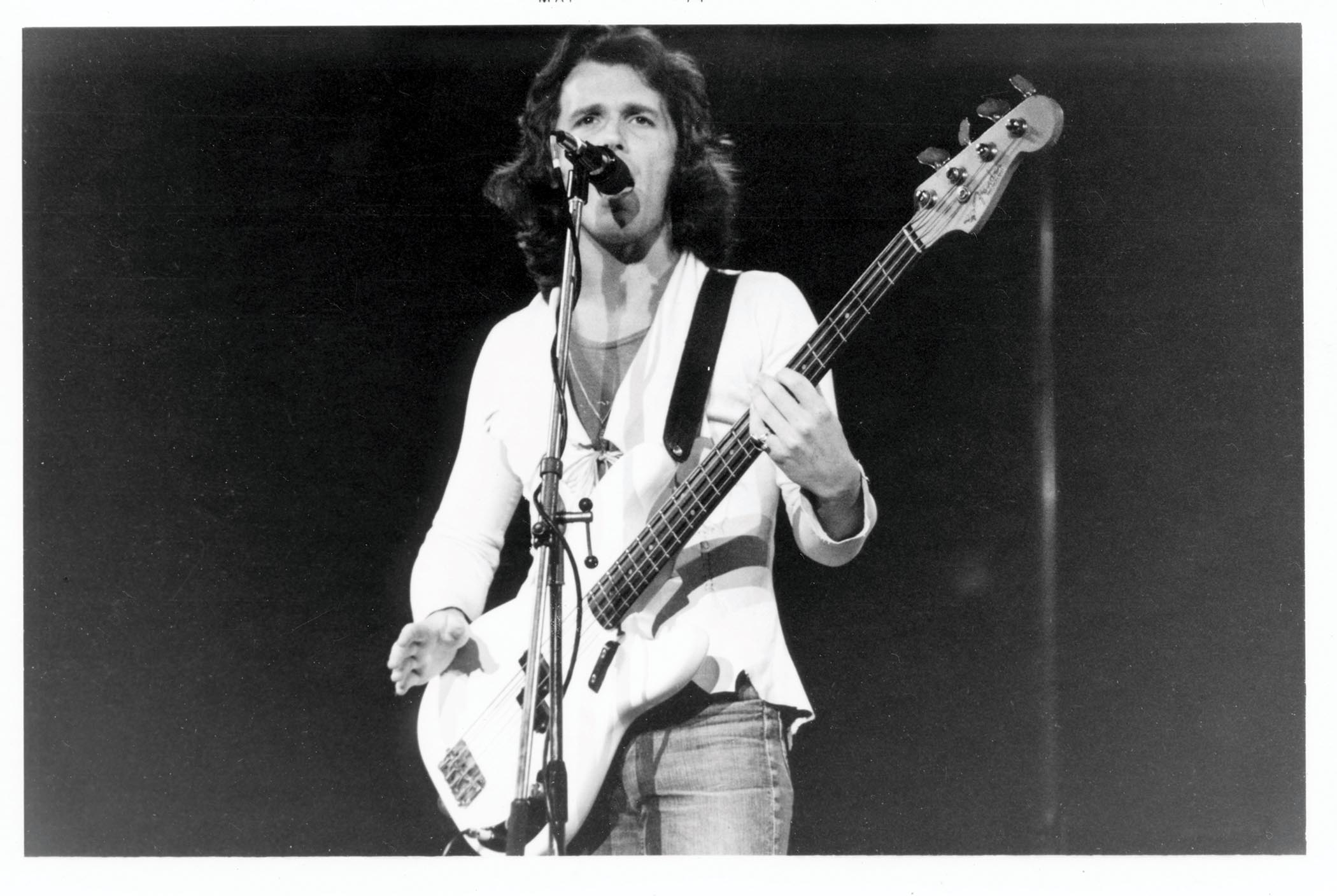

But tensions within Crimson’s ranks were escalating, leading to drummer Bill Bruford, vocalist and bassist John Wetton, and guitarist and mastermind Robert Fripp entering the sessions for the heavier-than-heavy album, late 1974’s Red, on the precipice of spontaneous combustion.

Lineup shifts, specifically the expulsion of violinist David Cross, had left Fripp feeling uneasy. This, along with the increasing sensation of needing to break away, manifested in Red’s ultra-heavy, yet still intellectually complex, atmosphere.

“The music is in the body,” Fripp tells Guitar World. “From there we might say, ‘Well, look, what’s going on here? How is the music speaking to us?’ And then we engage the head and express it formally, analyze it and so on. But the strength of Red is that the power is in the music.”

Songs like the hyper-urgent Red, the catchy yet chaotic One More Red Nightmare, and the sprawlingly beautiful Starless illustrate what Fripp refers to as his entry into the liminal zone.

“It was very, very open,” Fripp says. “But it’s a very difficult and uncomfortable place to be. If someone comes in with a pretty well-written piece of music and says, ‘Let’s play this,’ then it's relatively safe and straightforward. But the problem is, when you know what you’re doing, if you know where you’re going, you might get there, and that’s not an interesting place to be. Where you wish to arrive is where you could never possibly know you might be going. But that is a very difficult tension to hold together.”

Given the tension and mental gymnastics that came with it, along with the tepid response Red garnered, which was followed by Crimson’s collapse, one wonders if Fripp regrets the whole thing outright. But time has been kind to Red.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Many think of it as an unintentional yet intentional proto-metal masterpiece. True, some people hate it, but putting art out into the public is to be subject to criticism and hatred. With that, it’s up to the artist to determine how to filter that and how it affects their art.

“I would’ve stayed as an estate agent in Wimborne, Dorset, if I had known the grief that was coming my way,” Fripp says with a laugh. “I would have stayed in real estate!” Jokes aside, most would probably agree that Fripp did alright for himself as far as music – and Red – goes.

“That’s a very generous estimation,” he says. “But my approach has been, if you read your press, you read all of it. And if you read all my press, there have been – by and large – as many people who hated it as who enjoyed it.”

What prompted King Crimson’s shift into Red’s heavier territory?

We usually suggest or assume the music is determined by the so-called right of the writers or players. Another way of looking at this is that music actually seeks to become what it is by acting on the players. In other words, let’s ask the music what it required of those young players.

One of the difficulties of working with [Crimson lyricist] Peter Sinfield in 1971 was that Peter's idea for the future of King Crimson music was Miles Davis-esque, gentle Mediterranean-influenced improv. Peter had a holiday, I think, on [Spanish island] Formentera, and came back very vibed up about a gentle, Miles-leaning atmosphere.

Whereas at that time, my personal voice was speaking more [Crimson's sprawling and ambitious 1973 songs] Larks – Larks Part One and Larks Part Two. So the beginning of metal in Robert’s voice, if you like, began around 1971. I have this from my own notes. Although if you go back to 21st Century Schizoid Man, that was about as metal as it gets.

In that way, you could say Crimson was as proto-metal as anyone.

I saw a recent video on YouTube on the 10 precursors to heavy metal, and Schizoid Man wasn’t among them. That’s absurd. I mean, Ozzy, Master Osbourne, not only recorded Schizoid Man on a solo album, but he was always generous enough to acknowledge Crimson.

My diary entry for Monday, the July 8, 1974, the first day of recording, was: ‘Idea. Let everyone do what they want. Is that cowardice?’

The metallic – the powerful, metallic element – has always been there in Crimson. For me, it became increasingly articulated in the simple question: What would Jimi Hendrix have sounded like playing a Béla Bartók string quartet? In other words, the sheer power and spirit of the American blues‑rock tradition speaking through Hendrix’s Foxy Lady or Purple Haze.

Suppose instead there was a more European vocabulary, for example – Bartók and early Igor Stravinsky were very influential on me. Also, may I say Claude Debussy must be included in that with whole tone – the Debussy vocabulary was part of my epiphany as a young player, listening to all these different forms of music as if it were one musician playing all these different elements, one musician speaking in a number of dialects.

That, for me, was an epiphany and a driving force. Crimson’s music has always been perhaps more varied than some of the other bands working at the same time. So, moving on from Schizoid Man through Larks’ Tongues in Aspic and arriving at Red, a particular feature of Bartók's writing was his use of the golden section [or golden ratio].

That’s apparent in the title track, correct?

Red uses the golden section within it. So Red, in a sense, is very much in a European folk music tradition, as coming through Bartók for me. It was instinctive that, for example, with Red, why would it have a five into a four? The answer is, because that’s the way you play it, no intellectual analysis.

You strap on and rock out, and that's what comes out at the end of it. On the introduction, the vocabulary is, once again, from one point of view of folk vocabulary from Eastern Europe.

The second track, Fallen Angels, includes a lot of interesting guitar flourishes. How did you approach that?

You strap on and rock out, and some things work better than others. [Laughs]

So it was a lot of improvisation as opposed to being thought out?

Yeah, that’s it. I kept a diary at the time, and for the first time since I wrote it 50 years ago – and it was never written for publication, this is my personal diary, various mental exercises, how I’m addressing my day, my thought process, feelings, and so on – I went back to it this afternoon.

My entry for Monday, July 8, 1974, the first day of recording, was: “Idea. Let everyone do what they want. Is that cowardice?” And then it goes on: “Today, my life has changed: glimpsed possibilities and prices to pay.” That’s just personal notes to myself. Then we go on to Monday, July 15, with another quote: “[Bruford's] drumming begins to irritate me. Held myself back from passing opinions.” And so, on we go.

That brings up the subject of the chemistry and working relationship between you, Bill Bruford, and John Wetton.

Here’s one from Wednesday, July 24, 1974: “Argument with Bill Bruford. Bill says, ‘They might as well get a session guitarist.’”

I suppose things were a bit tenuous between band members by this time.

Yeah. And I think whenever I consider a situation or an event or an undertaking, there are four criteria I apply to come to a view or judgment: time, place, person, and circumstance. Now, 1974 was the beginning of my entry into a liminal zone. Liminal zones are between points and processes. Qualities of liminalities can be found in places, times, people, and processes.

The liminal zone is the in-between zone. Three characteristics of liminality are ambiguity, hazard, and opportunity; the situation is non-determined. In King Crimson, we were at the end of my first seven years as a professional musician in London, from 1967 to ’74, at the beginning of the next seven-year period, in which King Crimson comes to an end, and in ’81, where King Crimson begins again. So the making of Red was ambiguous, characterized by hazard, but also opportunity.

The liminal zone is the in-between zone. Three characteristics of liminality are ambiguity, hazard, and opportunity; the situation is non-determined

Opportunity, as in the making of the music or the openness to change?

King Crimson had moved from being a five-piece to a four-piece at the beginning of ’73. David Cross had just left, partly by his own volition, and partly because John Wetton, in particular, didn't see any further possibility of King Crimson with David. And this was an interpersonal tension at the time.

I was very fond of David Cross, but nevertheless, in the evolving power dynamic of Bill, a very energetic drummer, constant activity, and John, a remarkably powerful and increasingly loud bass player, the front line of David Cross on violin and myself, we were struggling to stay, not on top, but shall we say, alongside.

And David’s instrument was a violin, and at the time it was not amplified. You didn't have amplified violins generally. So David – you couldn’t hear him. He couldn't hear himself. On stage, John Wetton was so loud that the front-of-house man had to simply take John out of the PA system. Even then, we weren’t able to overcome John’s volume. These were the kinds of dynamics and tensions we were dealing with.

Would you say those frustrations manifested as the heaviness of Red?

Yeah, I do. I think that’s what gave it an edge.

One More Red Nightmare balances catchiness with controlled chaos.

I believe John’s part came from an idea from a song back in ’72. We’d been throwing around in improvs at least through ’73, and then in the studio, pulling the parts together, and the arpeggiated section at the end I think probably came from within the recording session itself.

Now, conventionally in Crimson, I preferred us to play material live so that it’s inside the body. So when we get into the studio, you just throw it away and go with the music, wherever it leads you. But since we had some experience working together, we were able to pull together a number of ideas that were already in the Crimson cyber world, if you like, and pull them together with some coherence.

The back half of Red consists of two sprawling tracks, Providence and Starless. Are those long jams, or was there a lot of puzzling together with bits and pieces?

In terms of Providence, the piece originally included on the Red album was edited down to eight minutes. And from the notes from my diary, which I consulted this afternoon, just for you, I saw from the notes that we were listening to several improvs that we'd recorded live just on the final tour in America, including another improv from Providence and a live track from Asbury Park, New Jersey.

The simple example that Bill Bruford generally gives is, well, we didn't have enough written or composed material. Yeah, that's one fair comment. The second is that improvisation was such an essential part of King Crimson, and improvisation in the studio, by and large, doesn’t have the power of improvisation in front of an audience.

Improvisation was such an essential part of King Crimson, and improvisation in the studio, by and large, doesn’t have the power of improvisation in front of an audience

Why? When the audience is there, you have a family like a father, mother, and child. You have music, the musician, and the audience. The audience is mother to the music. And if you’re improvising in front of an audience, there’s nothing like exposure to public ridicule to galvanize your attention. Now, if the drunk in the third row really doesn't like what you’re doing, the bottles might come flying this way.

So when you’re improvising or playing in front of an audience, there is always an element of risk and uncertainty that you won’t find in a studio. That conveyed a part of what King Crimson was musically; we chose something we came to a consensus on, and that became Providence.

Was it a similar situation with Starless?

John regretted that, when he presented this to us in 1973, we didn’t recognize it. Well, it wasn’t complete. And in ’74, we did recognize it, and we played it live.

But if you listen to the live tracks, you’ll find that the lyrics aren’t complete, and on some lines, you hear John singing, but he’s singing a line, and he’s articulating, he’s vocalizing sounds but the lyrics aren’t written.

So clearly, in 1973, at the time of Starless and Bible Black, the song Starless wasn’t completed. But we had the song, which was a stunning song, may I say, breathtaking and quietly heartbreaking. And when Crimson was playing this song from 2014 to 2021, I was closely in touch with John and would email him from the road.

We played Starless, and on occasion, it was hard to keep a tear down. But there we are anyway. So, we have Starless, and then at the end of it, Bill came up with his gang-gang sound.

Now, Bill said to me around 1972 at the beginning of Larks’ Tongues, “I see it as my job to give you 100 ideas. And it’s fine if you throw out 99 of them.” So Bill was happy to live with a 99 percent failure rate. Me, I think a 10 percent failure rate – where you present 10 ideas and one doesn’t work – is a better way to go. But Bill’s one idea in 100 that worked was stunning.

He came up with this idea, and I began playing the very simple one-note version on two strings, moving up slowly as the changes happen with anticipation and retardation where they move in respect of the changes. That line is referred to by Steven Wilson as the “death of the prog guitar solo,” because it does virtually nothing other than move up slowly and incrementally until it really opens out widely.

As far as gear, did you primarily use your ’59 Les Paul across Red?

You have my Gibson Les Paul and a Hiwatt stack. By and large, that’s really enough for anyone if they have a background in analog. But I used my Pete Cornish pedalboard, which had a volume pedal, fuzz, and wah-wah. And also a [Watkins] Copicat echo unit. And hey, that’s pretty basic, but at the time, to actually have a pedalboard was sophisticated. I mean, that’s astonishing, isn't it?

It is. Save for Frank Marino, few players had full pedalboards in the mid-Seventies. That’s relatively high-tech stuff for the time.

Well, what I did was introduce one technical innovation. If you plug through a pedal, you lose gain and the signal gets weaker. So I suggested to Pete Cornish that he put in a bypass pedal so you have volume, but you have to switch in your fuzz or wah-wah if you want to use them, and when you don't, you switch it out. Now, that sounds so dumb, but at the time, it was actually a technical innovation – astonishing! [Laughs]

One of the tricks we used to use, for example, are Marshall stacks, where you'd have four inputs onto a Marshall stack – channel one and channel two – with an input and output on each. Those in the know would put an input on channel one and lead it to an output on channel two. So channel two would crank channel one; it’s a simple analog technique that I learned in ’69, and boy, would that give you some crunch.

If you look at the back cover of Red, there’s a picture of a needle moving into the red zone, hitting a critical point where, I suppose, it will blow. There seems to be some symbolism there regarding the state of Crimson while recording Red. Seeing as you have your diary open, can you give direct insight into your mindset and what led to Crimson breaking up after Red’s release?

Looking at that today, what does that tell me? That tells me, “Hey, dude, crank it. Go for it as far as it can possibly go. No compromise.”

Looking at Fripp and Brian Eno [Fripp & Eno, officially], there’s the album title (No Pussyfooting) [1973], and the title came from what I wrote on a piece of paper at the session to record, meaning no compromise, no wussing out, because the management and record company aren’t going to like this. So, most “no pussyfooting” was the equivalent to crank. If there was going to be an alternative title for Red today, I would say call it Crank.

At the time, my direction in life was somewhere else. And moving through these diaries for the time, I saw myself going into retreat

At the time, my direction in life was somewhere else. And moving through these diaries for the time, I saw myself going into retreat. Here’s an entry: Saturday, July 13, 1974: “I went down from London to Wimborne to see my mum and told her that it was around the fifth of July, just immediately getting back from New York and the final Crimson show, that it became obvious to me that I had to leave the industry and go into retreat.”

And I told my mother, and this is a quote I had not remembered, where my mother said to me, “Why can’t I have normal kids?” [Laughs]

Anyway, for me, I had to leave Crimson, but that didn’t mean Crimson had to end. So, the question for me was how to keep King Crimson going as an authentic King Crimson – but without me. And in these various entries, an early one was where I’d called a violinist who worked with ELO, and maybe he would replace David Cross and keep the band going.

And I see that I called Steve Hackett on a number of occasions and that Steve was a guitarist who could maybe replace me. All of these are discussions underway, and I felt a responsibility to the band and the road managers because they had working lives, and I felt responsibility toward them.

But eventually, [manager] David Enthoven made it fairly clear to me that they weren’t interested in a King Crimson without Robert. So, at that point, I phoned up Bill and John and said, “Well, this is it.” So that, I guess, was that, and Bill wasn’t happy. There’s various quotes you’ll find from interviews at the time… I think Bill was disappointed. I think John was too. But what to say? I wasn’t able to persuade anyone about an alternative way of King Crimson moving forward.

Red wasn’t a hit, but in the years since, it’s become beloved, especially in the U.S. What’s more, it’s become very influential on heavy metal and prog. Tumultuous as it was, it seems like an important moment in your trajectory. How do you look back on it now?

It is one of the three Crimson albums that, for me, has a completeness or integrity about it, along with In the Court of the Crimson King and [1981's] Discipline.

Looking at it objectively – and as a fan – I can see why you feel that way. But I’d love to hear your perspective on why you feel that way.

Red is a complete and satisfying statement. In the Court is a complete and satisfying statement. Discipline is a complete and satisfying statement. If you didn’t have any of the albums in between, you would think, “Yeah, I can see this band's journey…” If you put the other albums in between, you can see how we got from Court to Red.

Discipline is interesting because it came completely out of the blue. No one could have seen that coming. On the other hand, how could it not have been what it was? You probably know that Red was the album found in Kurt Cobain’s CD player, and Butch Vig told John Wetton that seeing Crimson, I think in Salt Lake City in ’74, was a very powerful moment for him.

I do. Those stories only give credence to Red’s legacy and impact.

When Billy Sheehan was in Japan, I think in 2000, he invited me into the dressing room and began playing Frame by Frame on bass with Paul Gilbert. Billy later told me that if he had to take three albums to a desert island, Red would be one of them. And I trust Billy’s point of view.

Hey, look, I can’t make assessments on this, but those are the three pivotal albums for me. In the Court of the Crimson King and Red bookcase that first period, and Discipline somehow keeps it going – but from an entirely different dimension.

- Red: 50th Anniversary is out now via Panegyric

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.