“With the Crowes, you’d better step up to the plate and swing your bat – or prepare to get completely ripped apart”: Bassist Johnny Colt reveals the inside stories behind the Black Crowes’ controversial Amorica album

Colt hung around for one more album, before jettisoning himself from the band in 1997

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

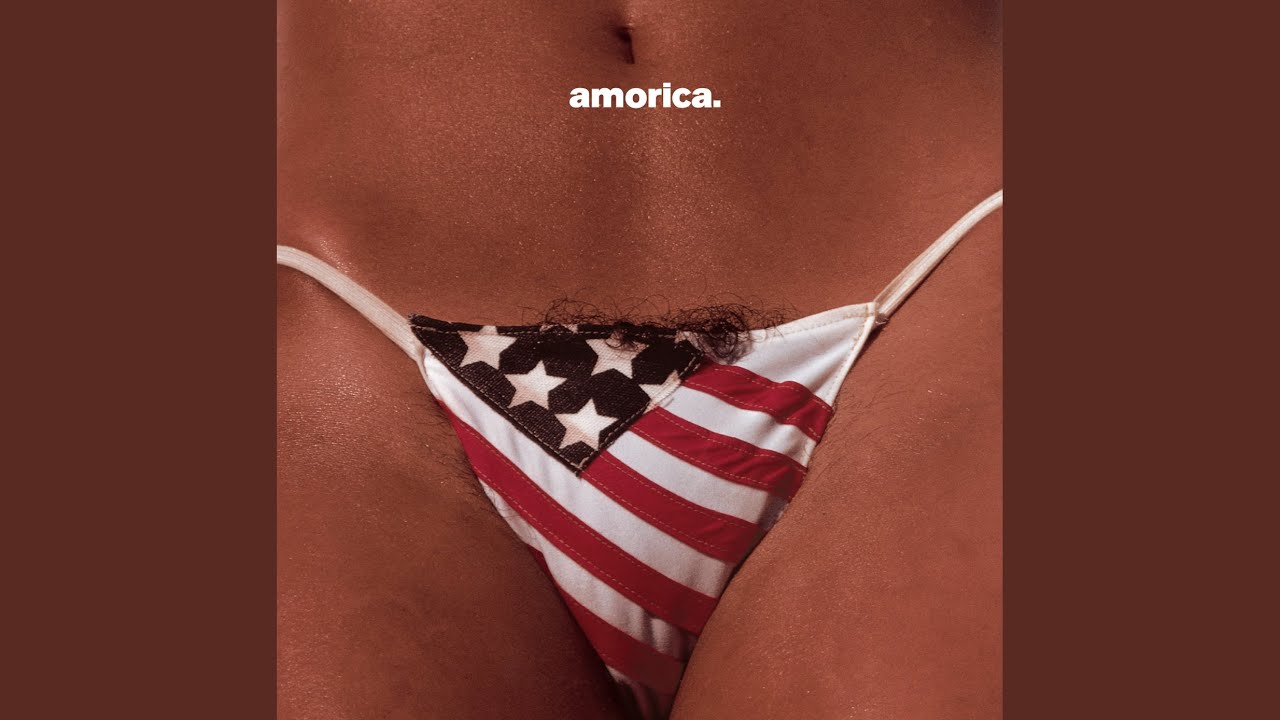

“It’s complete horseshit,” said Johnny Colt, former bassist of the much-maligned Black Crowes in the March 2005 issue of Bass Player. "You can walk into any store and look at the magazine rack – even in the so-called ‘Bible Belt’ – and you'll see a whole lot more than that. What about the Ohio Players’ records? What about the cover of Fire?”

Colt was talking about the banning of the band’s third release, Amorica, due to cover art featuring a closeup of a woman’s stars & stripes bikini-clad crotch.

Too hot to handle? Rolling Stone seemed to think so – the magazine wouldn't publish an ad displaying the cover. And K-Mart, Target, Wal Mart, and other ‘household-oriented’ chain stores refused to stock the record.

Article continues belowRather than alienate themselves and deny their fans in rural areas, the Crowes reluctantly authorized a second cover, but it still didn't sit well with the band.

Prior to the arrival of Stone Temple Pilots in 1992, the Black Crowes were the whipping boys of the rock press, who trashed them for a sound and look that channeled yesteryear elements of the Faces and the Rolling Stones.

They were weeded out for their candid views on marijuana legalization and for their “go as low as you can or as high as you can” lifestyle. They clashed with just about everyone around – including each other.

The result? Their first two albums, Shake Your Money Maker and The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion, sold over 10 million copies worldwide.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Their third effort, Amorica, was a striking fusion of blues, rock, soul, and gospel – and Colt's bass had never been more powerful. From the elegant, old-school feel of Nonfiction, to the fuzzed-out grind of High Head Blues, to the fretless-like glide of She Gave Good Sunflower, to the dropped-D chug of A Conspiracy, his high-caliber basslines expressed an energized, unspoiled approach.

“I put a lot of time into the instrument away from the band, and I think my bass playing improved a lot. Most of it was simply learning to listen. No bullshit – Amorica is the real deal.”

Alas, Amorica was also the product of many months of real turmoil. Singer Chris Robinson and his brother, rhythm guitarist Rich (the pair were sometimes called the “Rotten Twins”), were well-known for their frequent spats and moody mannerisms. Adding to the chaos, the Crowes parted company with George Drakoulias, who helped to produce the band's first two records.

Problems heaped upon problems, and the 17 songs originally recorded for the album were scrapped. Needing focus, the band finally enlisted the aid of producer Jack Joseph Puig, of Jellyfish fame.

“We've always been so hit-and-run in the studio that it was odd to spend that much time on a record, but it doesn't always happen when you're trying to go somewhere new.”

In the end, it was just “business as usual”, insists Colt, who's credited with “bass fishing” on the Amorica sleeve. “Bass fishing! Honestly, I'd rather fish for trout.”

Southern Harmony took six days to record, while Amorica took six months. What was the biggest obstacle?

Just locking in on where we were going, and trying to learn how to give each other space and grow as musicians. Striking the right kind of magic and laying it down is difficult when everyone's not in the same place – and we were coming from a lot of different places. But you don't get a record like Amorica without a fight. If you're going to push it, it's going to push back.

What made the working situation so volatile?

We toured for a long time after our first record – 20 months or so and came back home and slammed out Southern Harmony, and then went right back out again. When we finished that tour, a lot of stuff had changed: we'd gone from being 21 at the time of the first record to suddenly being 26. It all happened so fast.

We decided we needed to take some time away from each other, but when we did, that felt awkward. Once we did get back together, it was like, ‘This is fucked! We were knocking it out three months ago – what happened?’

The only thing that had kept everything in line for me was the band, and suddenly that was way off kilter. That was a large part of the cloud in my head.

Is turmoil part of the creative process for the Crowes?

Absolutely. Struggle is part of the creative process, period. The fights get bigger, but that makes the musicians push harder. I don't know too many happy-go-lucky types who can put paint on a canvas and create anything I'd want to look at. In fact, when most artists make great works there's usually some kind of crazy underlying problem, and that's always been par for the course with us.

Why the switch in producers?

After we finished Southern, we knew our relationship with George was over. He was extremely close to the band, and I don't think he wanted to tackle the task again. It was too upright, too big, too walkin’, and too talkin’ for him to deal with.

Jack Puig was originally hired to be our engineer. I can imagine how tough it must have been for him to walk into a situation like ours. With the Crowes, you'd better step up to the plate and swing your bat or prepare to get completely ripped apart. After working with him, we felt he could bring the vision.

What were the biggest changes Jack Puig made?

We were constantly trying new approaches and techniques. More important, he gave respect to the musicians, and he wasn't afraid to listen; he had sensitivity to both the songs and the players. He also helped to create a supportive, ‘Let's be better than you've ever been before’ environment.

It's funny, because every studio we work at starts to look the same – we bring in our rugs and posters of the greats like Coltrane. We even have Johnny Wong's Tiki Hut, which is a fully stocked bar with a bartender to wait on the band and the crew! So the cocktails and party supplies were there, and it was very relaxed. A little Bob Marley on the stereo, and we were ready to go.

I hear a bit more reach in your playing than on the first two albums.

On Money Maker, my parts were straight-ahead, because George wouldn't allow me to go anywhere. Then again, at the time, maybe if I had gone somewhere it would have been painful!

With George I basically had one day to record my parts for 15 songs; the line I got from him was, ‘Be a pro.’ Translation: ‘Get 'em done!’ Just like turning wrenches in a pit crew, get it done quick, and get it done right.

How do you know when you're onto a good bassline?

Well, I know when I'm not! I just feel it – it's there. It sings right out and catches all the right notes. The main thing is to not be scared to go out and find it.

Every once in a while I get a look thrown my way, like, ‘What the hell are you doin’?’ Then I give Marc the look, and he knows, ‘Oh, God – Johnny's going around the block!’ The bad thing is, if you do go around the block and come back empty-handed, it's a different story.

Sometimes I think, ‘What kind of chord is that?’ But the minute I figure out where we're going, I'll try not to play, so l'm not walking on any toes. That's when it starts to sound like music – and that's when the groove gets big. I enjoy space more than anything.

Do you care about selling records?

I was scared at one point that our first record sold too many copies, because I wanted to make sure we continued to progress as artists. I don't believe musicians who say they're not concerned with selling records, because if you're not here to be in the business – and there is a business involved – then what are you doing here?

What's the benefit of having sold 10 million records?

That I get to buy lots of cool basses!

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.