“I would like people to know that I was the true inventor of ska and reggae”: Ernest Ranglin on working with Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, James Bond – and how he influenced “almost every aspect of Jamaican music”

Bob Marley asked him to teach him how to play and how to write. He wrote music for Dr. No. He worked with Jimmy Cliff, Millie Small, and more. Ernest Ranglin reflects on his peerless legacy

Reggae and ska aren’t always associated with guitar heroics. And even when they are, most people’s mind’s eye wanders over to imagery of Bob Marley and his Les Paul Special or maybe one of Marley’s guitarists like Peter Tosh, Al Anderson or Junior Marvin. Such is life within an art form more focused on vibe than chops. But don’t tell that to Ernest Ranglin.

“People talk, but I was there,” Ranglin says. “I am a humble man, but I do know what happened back then.”

Ranglin is referring to this keystone work with a young Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, Millie Small, Monty Alexander, the Skatalites, Ken Boothe, Max Romeo and Bunny Wailer to name a few, which led to him essentially creating the sound of popular reggae and ska guitar.

“You can hear the styles of rhythm and the music in all my playing,” he says. “Sure, I like being called an ‘innovator,’ but I always just loved playing and creating for people and the world. That they got some enjoyment from my music is very comforting.”

Though he’s 93, Ranglin is remarkably sharp, if not wistful, when he reminisces on his career. “It seems amazing looking back,” he says. “But there was so much music in the air, and with the good lord’s help, I was able to create the music from that.”

Growing up as a youngster and in practice throughout his career, Ranglin was – and is – a devout jazz guitarist at heart. But that didn’t stop him from branching out. “I always wanted to grow as a guitarist,” he says.

“That is what brought me to do collaborations and explore different types of music over the years, not just jazz, ska, or reggae, even though I was the guy who invented that style,” he says. “I later did collaborations with musicians such as Baaba Maal from Senegal. I always wanted to travel to India… not sure if I am going to make it, but you never know. [Laughs]”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

To that end, Ranglin admits that while his mind is willing, these days, his aging body is fighting him. “I am 93, and I am really not playing too much,” he says. “But I still get the fire every once in a while.”

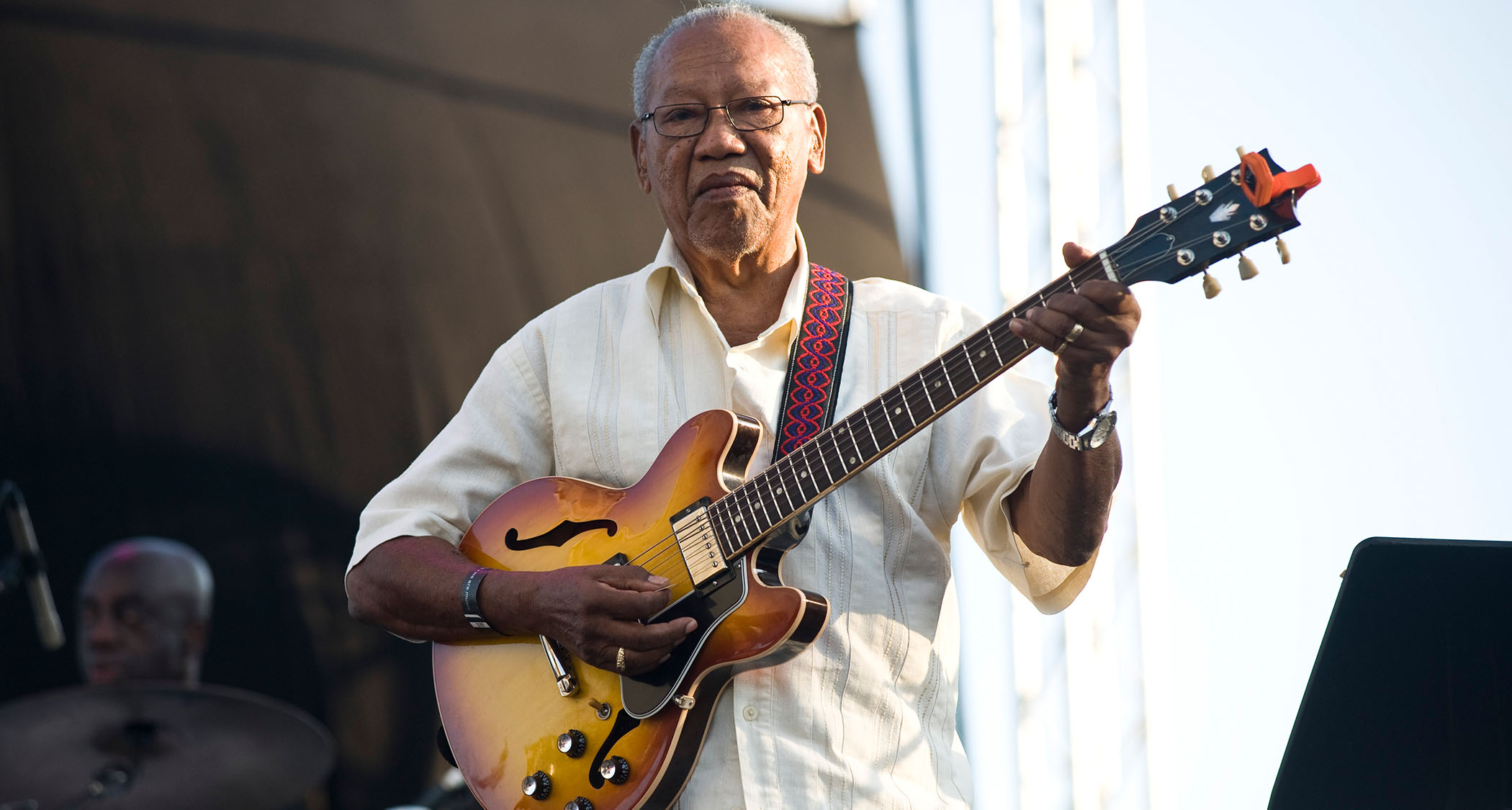

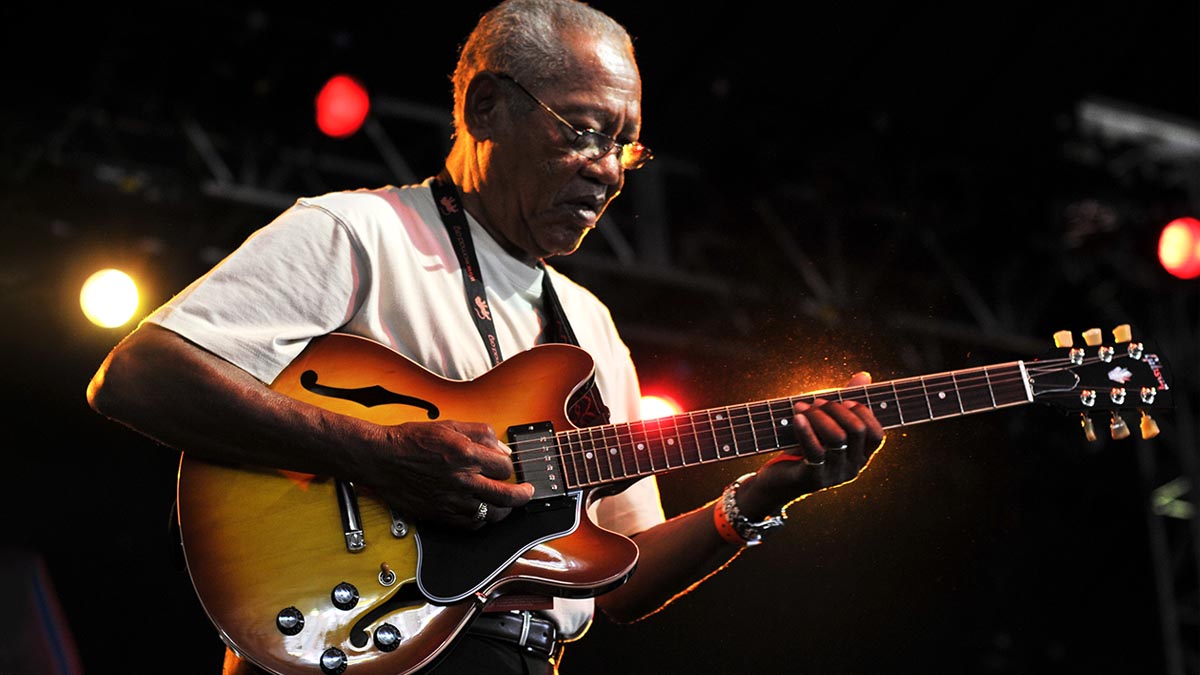

“And my hearing isn’t as good these days, but the fingers still move,” he says of the times that he does pick up his beloved Gibson ES-175 or Ibanez Joe Pass model. “I always say I will find that note. I love my classic guitars. Oh my, they are beautiful.”

Ranglin has been out of the recording game since around 2008. And considering his advancing age, the odds are that that won’t change. He’s more into playing his guitar when he’s able, and looking back, though the latter isn’t always easy, especially when it comes to measuring his impact.

“It is a little hard to answer that,” he says. “It is not really for me to say necessarily. I still think I can play, but I am pretty quiet these days. I am glad I have been able to do what I have done in music. Most people in my profession don’t make it this far. [Laughs] But I am appreciative to have had such a long career in music, truly.”

What sparked your interest in playing guitar?

When I was around four or five years old, I heard two of my uncles playing, and I knew right then. I would wait for them to leave and go to work and then try to figure out what was this thing. [Laughs] But certainly, I did not know what I was doing.

So, when did you start to take the guitar seriously?

I didn’t start taking it seriously until I was a young teenager. I just used their guitar when they left town, and then I was able to get a clunky guitar that was always out of tune. I think that helped develop my ear in the end. I will say I have collected many amazing guitars over the years; I would even work on them a little bit.

Did the guitar come easily to you?

Like many beginning guitar players, I just started playing what sounded right to me and my ear, which was pretty limited because I didn’t know what I was doing. At first, I was playing by copying whatever I heard by ear, so to speak. By the age of around 14, I decided that I wanted to play seriously. I made up my mind; it was what I wanted to do, be a guitar player!

You’re mostly self-taught, right?

I couldn’t afford a tutor, so what I learned from books, and started at the beginning. What was the book First Steps in Guitar Playing. I kept going to each level, and I even learned about chord changes through those and other books similar to that.

Was playing live around your area a big part of your coming of age as a player?

Now, from there moving on, my very first break in live work was when I went over to the Cayman and Caicos Islands to play for the tourists, even though my parents were against me becoming a musician. They thought it would lead to, what shall I say… an unseemly lifestyle. I also wanted to prove to them that I didn’t go to school and waste my time, so they saw my education come to something.

Can you describe the music scene you were exposed to coming up, and how it impacted you?

I grew up listening to my mother play the organ in church and church music, but we would listen to music from America. I loved jazz from the moment I heard it, and this was what was popular when I was growing up. I loved the great Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Prima, and Charlie Christian.

I heard how to play and the style of Bird, and thought, “Wow!” There was a whole blend of music that… how would you put it… permeated through the island, Caribbean mento and calypso with American jazz and R&B. As time went on, music was always evolving, and that was always part of my spirit. I found my own style, and it was rooted in all these types of music.

How did you find your sound, and what did that look and sound like?

Well, like I mentioned, I started in a jazz tradition, but I was also self-taught, so I think there were many factors. I played in my first band when I was fifteen or so. It was Val Bennet’s band, and it was just great with horns. It was such an eye-opening experience.

I would watch and listen and even look behind at their music stands for the notes and what the different keys were because horns had their own key/concert signature. It really helped me later to learn as an arranger. But honestly, I would never say I found my sound… a style perhaps, but I am always trying to grow.

Since you were into jazz early on, did you want to be a jazz guitarist?

Yes, that was what I played for a while. When I got my first break, it was with a jazz band. We would play at hotels, and I started playing with big bands. We would do Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and I had a band playing mainly on weekends at the Half Moon Hotel. We even sometimes shared the bill with Clancy Heywood’s band from Bermuda.

How did you get into playing calypso music, which essentially led to you creating the sound of reggae guitar?

Well, that type of music was all over, and I played in Bermuda. It was an interesting time, and reggae came later after I got back from England. But the calypso and mento were in our soul, so to speak. Then, we started with the music coming out of New Orleans, like R&B, and the shuffle.

Of course, I don’t remember getting paid very well or real credit, but the movie was cool, ya know? James Bond…

I was working at the Jamaican Broadcast Corporation [JBC], and Coxsone Dodd, who had one of the big sound systems, was starting to do recordings. We would hear the R&B music from America, and the demand in Jamaica made it possible to start doing these recordings.

I was Coxsone’s musical director and arranger. He and I kind of had the same vibe and feeling about the sound, and as the story goes, we went up into the studio one Sunday, and by Monday, we had the ska rhythm, and I put the sound to the paper.”

What gear were you using once you got into session work?

“We used a lot of borrowed gear from the JBC. I had old Phillips amps, and I seem to remember early Fender amps, and [inventor] Hedely Jones’ amps were important. That was some of my original tone. It was so long ago, but I am pretty sure I used that on [Millie Small’s] My Boy Lollipop. I had a Guild hollow body, but we also used what was available to us.”

What’s the story behind you composing the music for the James Bond film, Dr. No?

Well, that was interesting because they were filming the movie, and they had the musical supervisor [Monty Norman]. They came to me because Carlos Macolm was the musical director at the JBC, and I worked there, and he hired me to create a more “island sound.” They realized they needed some authentic sound to help the film.

I was known to have the arranging skills, and as someone who could work with the “professional” person to give the island vibe and sound. Of course, I don’t remember getting paid very well or real credit, but the movie was cool, ya know? James Bond… [gestures like James Bond shooting a gun].”

How did you meet Chris Blackwell?

Chris Blackwell was actually able to get me an audition and gigs at Ronnie Scott’s, where I was able to show my guitar style

I met him while working on the music for the James Bond film [Dr. No]. Chris then came and saw me at the Half Moon Hotel while I was playing in bands there. He was just getting started in the business and he seemed to like how I was playing. [Laughs] He contacted me really quickly after he saw me play.

He had recently founded Island Records, and he thought he could take the Jamaican sound international. He was actually able to get me an audition and gigs at Ronnie Scott’s, where I was able to show my guitar style. People and many of the big guitar players from England would come by; it was pretty humbling.

But that was also when Chris brought out the singer Millie Small and had me arrange music for her. We did an arrangement of My Boy Lollipop with mostly English studio musicians… they finally got the feel, and the rest is history. It sold millions of records.

How did you become involved with the Wailers’ early track It Hurts to Be Alone?

As far as It Hurts to Be Alone, it was before Chris signed Bob Marley and the Wailers. I was the musical director and arranger at Studio One, and this skinny young boy [Bob Marley] and his friends, Neville Livingston and Peter Tosh. They would hang around all the studio and sing harmonies and American R&B.

What did you think of Bob and the Wailers after first hearing them?

They got better as they practiced, and Coxsone and I decided they had something. I basically took what Bob had, and it was funny; he was so green, there was no beginning, no end to the songs, no real structure at all.

I basically arranged and essentially co-wrote the tune and played on it. I will say there was something special about Bob. We all could feel it. He later asked me to come on the road and not just teach him how to play guitar, but to teach him how to be a true arranger and composer.

Speaking of the road, you later toured with Jimmy Cliff. What was that like, and what gear did you use?

Yes, I was Jimmy’s musical supervisor for a good part of the ’70s. He was also a charismatic personality, but I also taught and influenced his sound and style. By then, I believe I was using my Gibson [ES-]175 and [Roland] JC-120.

What do you remember about recording guitars for Max Romeo in 1977, Bunny Wailer in the early-’80s?

Max was a sweet man and kind man and always nice to work with. Bunny was a big personality but super-smart and knew who he was really into the Rastafari and was always true to his work. I always brought my thing to whatever I was working on, but I was always trying to grow and challenge myself, and working with others always made that possible–so many different personalities and talents.

Would you say that jazz guitar requires a different approach than reggae and ska?

Well, jazz was and is always a true love and to come back to. I like so many different sounds and styles of music. Of course, they require different techniques. Jazz has much more chord changes and patterns, and ska and reggae are very different in that it is less technical but has a real specific feel, more reduced in those changes. They all require specific techniques, and at the end of the day, it is all about a feeling.

How do you view your accomplishments and influence when you look back?

That is tough for me. I do feel like I have influenced almost every aspect of Jamaican music, and that while many people know, many people haven’t heard about my contributions. But I always served the music and the muse. And I have had a long and healthy life with a loving family and a musical family. It is good to be able to look back and know you were there for all of it.

You, along with Lee Scratch Perry and Clancy Eccles, essentially created the sound of reggae as we know it. What are your thoughts on that?

Well, what is there to say except I was lucky enough to be part of the creation of a sound that truly became universal and transforming. Scratch was one of a kind, and Eccles was multi-talented… even as a tailor! [Laughs] But again, there was a sound coming up, and boom, now it is culture. It is worldwide, and to have been a big part of that is very gratifying.

How do you hope to be remembered when it’s all said and done?

I want all my music to be remembered as pleasing, reasonable, and that people got some joy from listening to it. I am a musician who has worked hard, sacrificed a lot for the music, you can say, gave my life to the music, and while I certainly did not become rich, I feel like I would like people to know that I was the true inventor of ska and reggae.

- Wranglin' is available to preorder, out on November 14 via Sowing.

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.