“That one’s a ’62. It’s also been shot. There’s a mark on the bottom where the bullet went in”: From his legendary Franken-Les Paul, Old Black, to his Hank Williams-owned Martin, and a pedalboard “ugly button,” Neil Young's rig is like no other

“When it comes to equipment, the idea with Neil is that you don’t change anything,” Young's guitar tech, Larry Cragg, told GW in 2009. “You don’t even think about it”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This interview with Neil Young guitar tech Larry Cragg was originally published in the October 2009 issue of Guitar World.

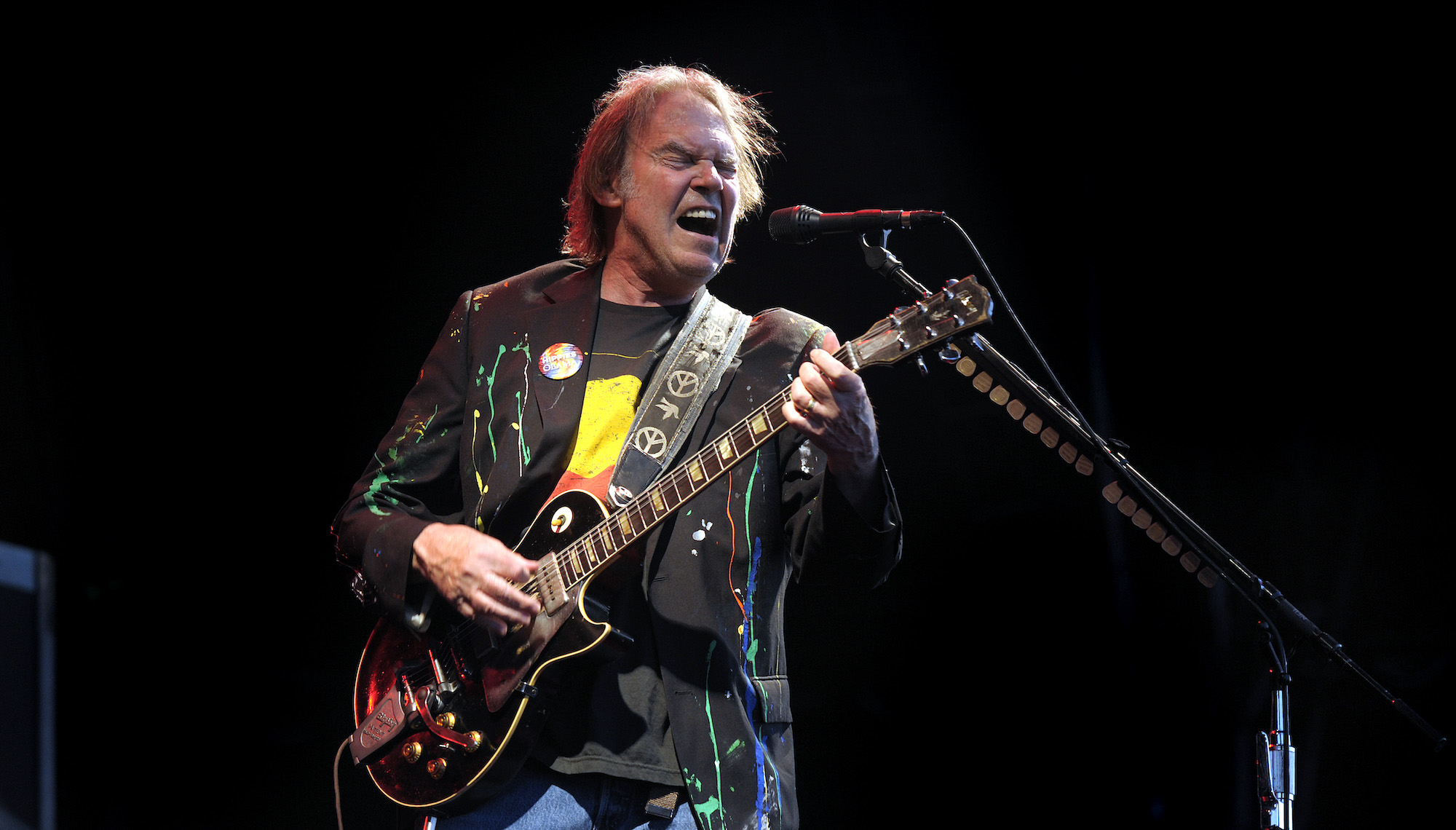

From his beat-up Les Paul to his battered amps and vintage effect pedals, Neil Young's stage rig is a road-worn tribute to his timeless sounds.

“When it comes to equipment, the idea with Neil is that you don’t change anything,” says guitar tech Larry Cragg. “You don’t even think about it.”

Cragg is himself among the many constants in Young’s gear universe, having worked for the musician since 1973. A respected guitar repairman – he’s been Carlos Santana’s go-to guy for 40 years – who also owns his own vintage instrument rental company, Cragg first met Young while at Prune Music, a guitar shop in Mill Valley, California.

“At first I was just fixing his guitars,” says Cragg. “But a few years in, he was on the road in Japan when I got a call from his people saying, ‘Get on an airplane!’ And I’ve done every tour since.”

Young brought his standard rig out on the road for his 2009 tour, a mostly electric guitar-dominated jaunt. True to Cragg’s word, his setup has remained largely the same over the years. But if Young is consistent in the equipment he uses to create his sound, the various pieces of gear also tend to be as idiosyncratic and susceptible to change as the man himself.

At the center of it all is the volatile 1953 Gibson Les Paul goldtop Young calls Old Black. A brutal and battered beast, the guitar is responsible for the legendary gritty tones heard on countless Young classics, including Cinnamon Girl, Down By the River, and Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black).

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Les Paul, which features a Bigsby tremolo and a P90 pickup in the neck position, received the black paint job that inspired its nickname prior to being acquired by Young.

Since then, it’s undergone several further modifications, including the addition of a “chrome-on-brass” pickguard and back plates, a bridge-position Firebird pickup, and a toggle switch, installed between the two volume and two tone knobs, that acts as a bypass. “You flip that,” says Cragg, “and the Firebird goes straight to the amp.”

Cragg installed the Firebird pickup back in 1973. “Originally there was a P90 in there,” he explains. “But in the early Seventies the guitar was lost, and when Neil recovered it a few years later the bridge pickup was gone. He put a Gretsch DeArmond in there for a while, but when I came onboard I replaced that with the Firebird, which has been there ever since.

“Everyone calls it a mini-humbucker, but it’s not. It’s a humbucker, and it’s very microphonic – you can speak into it. It’s really piercing and high and a big part of his sound.”

Old Black remains Young’s primary electric for both studio and live work, but he has also of late been making ample use of his 1961 Gretsch White Falcon onstage. Cragg says, “That’s the real deal. Neil’s had it forever. It’s kind of green-looking and really stunning. There’s probably only 10 or 11 of those around.”

The guitar, a stereo, single-cutaway model, figured prominently in Young’s work with Buffalo Springfield and CSNY, as well as on solo songs like Words (Between the Lines of Age).

Other electric guitars used by Young on his recent tour include a 1956 Les Paul Junior of Cragg’s that he calls a “really rude, in-your-face killer,” and a second ’53 goldtop that the tech assembled as a stand-in for Old Black.

Cragg says, “I put that together around the time of [1990’s] Ragged Glory, and Neil used it on about half that album. It’s not black, but it’s got the metal pickguard and covers, the Firebird pickup, everything. It feels different, but it still kicks butt. It’s a little more powerful and a little less piercing than the original.”

For his touring acoustics, Young has been relying on a trio of Martins, all equipped with Cragg’s stereo FRAP (Flat Audio Response Pickup) transducers: the 1968 D-45 used to record much of 1972’s Harvest; “Hank,” an early Forties D-28 formerly owned by Hank Williams; and a second D-28 that Cragg tunes to what Young calls “A# modal” [low to high: A# F A# D# G A#].

“That one’s a ’62,” Cragg says of the detuned guitar. “It’s also been shot. There’s a mark on the bottom where the bullet went in.”

Cragg uses D’Angelico 80/20 Brass strings (.012–.054) on Young’s acoustics, and Dean Markley Super V’s (.010–.046) on his electrics. Picks are nylon Herco Gold Flex 50s. “Neil used those when I first started working for him, and he still does today.”

At the core of Young’s amplifier setup is a piece of gear as essential to his sound as Old Black: the 1959 tweed Fender Deluxe he’s used since the late Sixties.

A small, 15-watt unit, with just two volume knobs and a shared tone control, this amp, says Cragg, “makes all the sound. Onstage, as loud as everything gets, that’s what you hear. And it’s totally stock except for two 6L6’s in place of the original tubes. That boosts the output from 15 to 19 watts, and it kills.”

An added consequence of this rebiasing is that the amp runs extremely hot; Cragg has high-powered fans trained on the back of the Deluxe to “keep it from blowing up.”

Young derives his distortion entirely from the Deluxe’s output-tube saturation. He coaxes various gain stages from the amp using a device called the Whizzer, a custom-made switching system he and his late amp tech, Sal Trentino, developed around the time of the Rust Never Sleeps tour in 1978.

A high-tech concept housed in a rudimentary box, the Whizzer boasts four preset buttons, each corresponding to one volume/tone configuration on the Deluxe. Young accesses the presets through footswitches on his pedalboard, which, in turn, command the Whizzer to mechanically twist the Deluxe’s tone and volume controls to the programmed positions.

All four of the Whizzer’s presets dial in distorted tones on the Deluxe.

“The first one,” says Cragg, “is still clean enough that Neil can get really nice dynamics, depending on the way he picks. The second setting is the one he uses on songs like Hey Hey, My My, and the third one is really distorted.”

The final setting, which moves the Deluxe’s main volume and tone knobs to 12 and the second volume control to roughly 9.9, produces a sound that, says Cragg, “is basically a woooaaarrr type of thing.”

Cragg pads down the output from the Deluxe and feeds it into a Magnatone 280 with stereo vibrato combo amp, and a Mesa/Boogie Bass 400 head with the highs EQ’d out. The latter amplifier is run through a massive Magnatone speaker cabinet that sports “eight horns, four 10-inch speakers, four 15-inch speakers, and two 15-inch passive radiators.”

The stage rig is rounded out by a 25-watt tweed Fender Tremolux of Cragg’s that the tech rebiased to run at 40 watts, as well as a “high-powered, four-6L6” tweed Fender Twin.

Cragg uses a combination of Sennheiser 409 and Shure SM57 microphones on the amps. Young’s reverb unit, a stock, brown-tolex-covered Fender model, is stationed behind the wall of amplifiers. “We have three plates for that,” says Cragg. “We only use one at a time, but they all sound different.”

Young controls everything from an oversized, red wood pedalboard at the front of the stage.

The slanted portion features five buttons: one for each of the four Whizzer presets, as well as a reverb kill. Across the top panel are switches for, variously, a Mu-Tron octave divider; an old, AC-powered MXR analog delay; a Boss Flanger in a “blue, cast-metal box”; and an Echoplex. All are housed inside the board. There is also an effect-loop bypass and mute/tune option, as well as a switch that Cragg refers to as the “ugly button.”

“That’s a very strange thing, and Neil only hits it when he wants to go to the next level,” he says. “It activates a unit that’s just totally freaked out.” Cragg laughs. “It’s adjusted how it definitely should not be adjusted. But Neil seems to like that.”

- This interview was originally published in the October 2009 issue of Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.