Eric Clapton Discusses His Star-Studded J.J. Cale Tribute Album, 'The Breeze'

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Robert Johnson and J.J. Cale represent the yin and yang of Eric Clapton’s musical influences.

On one side is Johnson, the famously troubled Thirties-era Mississippi bluesman who moaned about hellhounds on his trail, spooks around his bed and those lowdown, shakin’ chills.

On the other side is Cale, the famously laidback singer-songwriter from Tulsa who penned laconic odes to singin’ whippoorwills, “chugalugging” and shakin’ tambourines.

Clapton has covered the music of both men on several occasions throughout his career, taking Johnson’s “Crossroads” to the heights of blues-rock jam-outs with Cream in 1968 and earning massive commercial success as a solo artist with his versions of Cale’s insanely catchy “After Midnight” in 1970 and breezy “Cocaine” in 1977.

Yet, when looking back at Clapton’s work as a whole, one can’t help but notice that the Cale-influenced side of the equation takes up a much larger chunk of the pie, which was probably the result of the fact that Clapton actually got to meet and hang with Cale. Their bond lasted from the Seventies until Cale’s death in 2013 at age 74.

Clapton even had Cale’s phone number, something he’s still tickled about.

“Nobody had his phone number. You had to be in the inner circle to have that,” Clapton says with a laugh. “I’d call him, and sometimes I’d get his voice mail. Other times, I’d get him on the line and we’d talk for hours. I felt I had some kind of inside track, and that was a wonderful thing.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

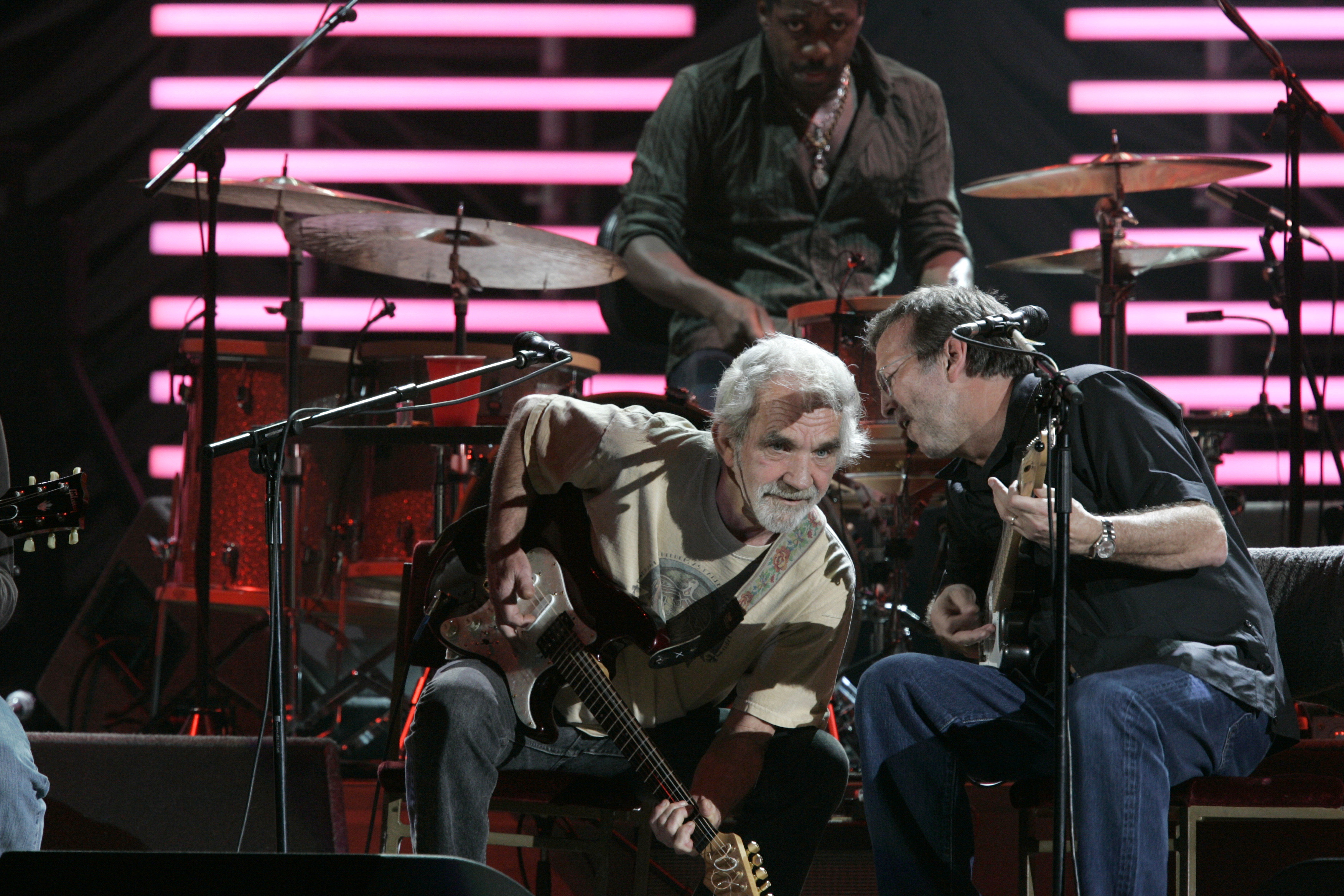

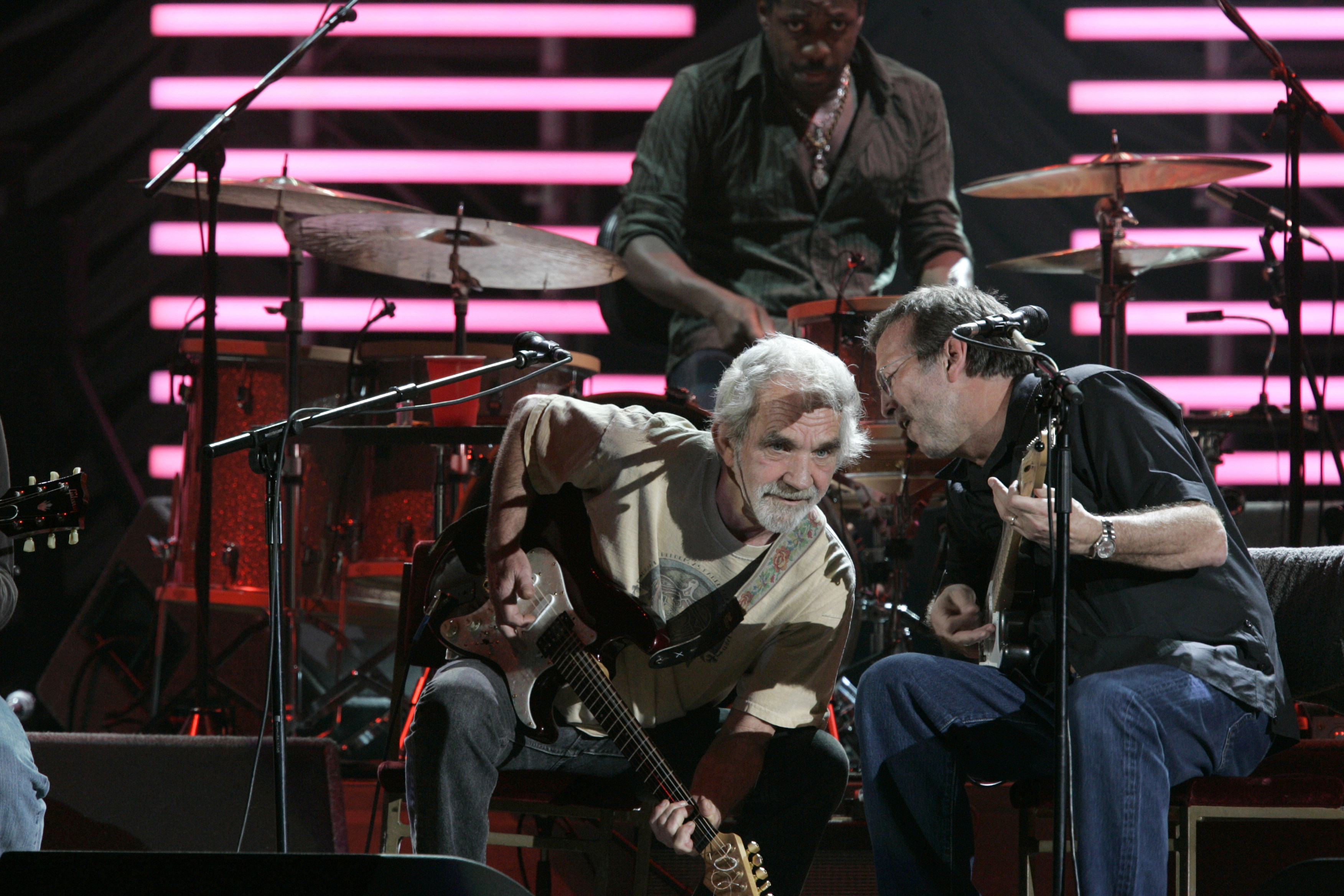

That inside track led to The Road to Escondido, the duo’s Grammy-winning 2006 album, appearances on each other’s most recent solo albums (Cale’s Roll On from 2009 and Clapton’s Old Sock from 2013) and a joint performance at the first Crossroads Guitar Festival, in 2004.

Over the years, Clapton assimilated and mastered Cale’s approach to songwriting (“Lay Down Sally,” “I Can’t Stand It”). His mid-Seventies and early Eighties albums, from 461 Ocean Boulevard (1974) to Money and Cigarettes (1983), come off as loose acknowledgements of Cale’s influence.

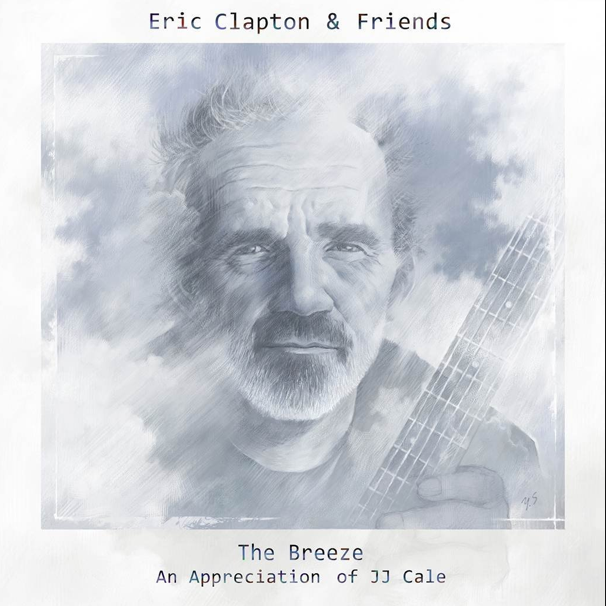

On July 29, however, Clapton released a bona-fide tribute to his friend and former collaborator: Eric Clapton & Friends: The Breeze, An Appreciation of J.J. Cale. The album features 16 Cale songs—from “Call Me the Breeze,” “Starbound” and “Lies” to “Magnolia” “Songbird” and “Crying Eyes”—performed by Clapton and a host of guests, including Mark Knopfler, John Mayer, Willie Nelson, Tom Petty and Don White. Other friends include Albert Lee, Derek Trucks, David Lindley, Doyle Bramhall II and Don Preston, all of whom split up the six-string duties.

In the interview below, Clapton discusses Cale and the new album—which happens to be his only tribute album besides Me and Mr. Johnson, his 2004 homage to Robert Johnson.

It’s 1969. You’ve left behind Cream’s heavy blues-rock, extended guitar solos, freeform improvisation, high intensity and volume. Then you discover J.J. Cale’s music, courtesy of Delaney Bramlett of Delaney & Bonnie. Before you know it, you immerse yourself in Cale’s “relaxed” Tulsa style, and the Clapton of Cream becomes a thing of the past. Did you see Cale’s music as the embodiment of something you had been seeking? Or were you not even looking for something new?

I think I was looking for someone to identify with. A lot of my musical growth and education came from players who weren’t around anymore. The Best of Muddy Waters [1958] was one of my primary sources of education, as well as a lot of the country blues guys who had been gone a long time. But even the Muddy album, which was an electric album—that band, by the time I got to hear that album, was long gone.

What I’m trying to say is, if I was looking for something current, there it was. He had the root and the understanding—the knowledge about all the music I loved—in the same way Delaney and Leon Russell did. These guys understood the history of this thing I was attracted to, so it was logical to me that I should keep an eye on them and follow what they were doing.

Sometimes you immerse yourself in your influences to the point that you ignore your own ego and delve into the artist’s style, even including the way he sings and plays. When that’s the case, do you consider it a learning experience or some type of comfort zone?

A bit of both, I think. With J.J., for instance, and trying to learn to play some of the Robert Johnson songs…when you put those two things side by side, my intention is always to try and leave my ego at the door and go in and learn everything I can about how they did it. That’s the starting point. That will be the aspiration. And what happens inevitably is that my ego gets back in and I adapt what I’m learning to suit what I want to do. So my will is always present.

Robert Johnson was the hardest thing to tackle because, in order to play any of the songs he put on tape exactly as he did it, that’s a life’s work in itself. Any one of his songs, they’re so strategically different in terms of technique and how to sing and play those things at the same time. It’s like master-class stuff. My approach is to get as far as I can and allow my will to come in and take over and make it so that I can play it now and not in five years’ time, because I’m too impatient to have to follow that through to its logical conclusion. And with J.J., it’s the same thing. So what I end up with, even if I’m trying to imitate and emulate, is a version, because my will has twisted me to make it easier for me.

What was it about Cale’s music or approach that appealed to you the most?

He had it all, and I mean everything. He was the epitome of a rock writer. He could do the whole thing. When I found out he produced and mixed and made all these records himself, well, that’s as good as it gets.

He also employed what can be called a minimalist approach, something that’s long been associated with the blues. Did you see a connection between Cale and the blues in terms of doing a lot with a little?

Yes, but having said that, I think that might have been an illusion. The more I delve into how he did what he did, the more complex and sophisticated it becomes. The initial impression of J.J.’s music is that it’s simple, laidback and quite plaintive in a way. But in truth, if you put a microscope on it, it’s really quite ornate.

Also, J.J. would play solos in the back of the track that were fuzzy and distorted. He was happy to do all of that stuff—wah-wahs, effects. He was Mr. Effect. He was in front of the curve with all that stuff. He and Roger Linn kind of invented the drum machine [Linn was the first to use digital audio samples in a drum machine, the LM-1 Drum Computer]. I think J.J. was the field guy, the development guy, for a lot of those people. I don’t think he gets enough credit for being at the front end of all that technological stuff.

How, when and where did The Breeze, An Appreciation of J.J. Cale come together?

Right after his funeral service, I flew from California back to Columbus, Ohio, where I have a house, and my wife’s family is there. At some point over the last couple of years, I started putting in a primitive little studio, and we started tracking there. I’d put rhythm tracks together and then I’d overlay guitars, and Walt Richmond came to play keyboards.

Then, when we’d built enough with the artificial sounds, we went to L.A. I asked [drummer] Jim Keltner and [bassist] Nathan East to start putting down a proper rhythm section. Then we got some other players, including [drummers] Jamie Oldaker, David Teegarden, Jim Karstein and James Cruce. Then came [guitarists] Don White, Don Preston, David Lindley, Doyle Bramhall II, all to kind of build the sound.

Jamie Oldaker was in your Seventies band. Does this mark the first time you’ve worked with him in, I’m guessing, three decades plus?

In a long, long time, yeah. He was one of the first people I met who truly understood what J.J. was trying to do. Being another Tulsa boy, he spoke the language.

What would you say is the commonality between you, Mark Knopfler, John Mayer and some of the other guests who appear on the album?

Well, I don’t know about their taste, but I can make an assumption that J.J. would be high on their list of favorite people. I didn’t want to get just famous people or people who are commercially attractive or who were skillful or whatever. They had to be people who had a certain affection for J.J. and vice versa, and that J.J. would’ve approved of doing the songs. There were some criteria there, but the most important thing was that J.J. had had an effect on them.

How did you choose which songs to cover on the album?

When I got the news of [J.J.’s] passing, I booked a flight to L.A. and they told me the date of the service. I flew from London to L.A., and during that flight everything happened. I listened to everything I had of his on my phone. I had most of his catalog in a playlist and thought this would be good opportunity to do some of his songs.

In terms of individual choices, “Cajun Moon” was very daunting to me. I didn’t think anyone could do that one, but I thought I could give it a try. I made up a short list of about 30 songs. Then I went back to Columbus and we just started putting down tracks. Then I realized, having met Don White at the funeral, that I needed to open this up to other people. He was the first person I asked. Then I asked John Mayer. Then I asked Tom Petty. Then I asked Will [Nelson] and Mark [Knopfler]. And I left a little room for myself.

What amps and guitars did you use?

I used a Dumble Fender amp, which is a Fender Bandmaster that [custom amp builder] Alexander Dumble had done some work on. I also used a vintage Fender Vibrolux and a vintage Fender Champ. Then there was my Martin signature guitar, a Sixties Gibson ES-325 and a Signature Fender Strat. I also have a beautiful Gibson L-5 that J.J. gave me, which I used as a rhythm guitar.

Do you try to tweak your sound so that it’s slightly different from project to project?

I don’t think I would do that deliberately. I kind of do the opposite. My experience is, no matter what you do to try and remain consistent, it’ll always change. There’s something in the air. Further on down the road, there will be something different, and my intention would be to pick up where we left off. For that reason, I always try to work with people I trust and love, like my partner [and album co-producer] Simon Climie, and Aaron Douglas will be our engineer. We know one another, and we try to get some consistency from that point of view. But you can’t account for everything. Even the weather might have an effect on what you’re trying to do. [laughs] So I go the other way. I try to follow a thread.

Along the lines of learning, say, finger vibrato from B.B. King, what was the main thing you picked up from Cale as a guitarist, or even as a producer?

I think it’s a philosophy that becomes much more of an overall way of approaching how to play music, starting with a much lighter touch and a more open ear, being much more attentive to the peripheral sound of everything rather than just jumping onto a moving train, as it were, and playing away. J.J.’s thing was creating a really interesting picture, whatever kind of track he was working on. That was attractive to me, and I tried to learn about and embody that., even in stuff that doesn’t particularly sound like that kind of music. I could be working on something else, but I’ll still apply that philosophy.

How would you describe your relationship with Cale?

We came into one another’s lives too late to be close friends. We were good friends, but his close friends are the guys who grew up with him and knew him from the school yard.

When you recorded The Road to Escondido together, why did you want him to write the bulk of the songs?

I was too intimidated to come up with any. I couldn’t write. I was kind of nervous going into that project, so I stalled, I froze with the writing, and he sent me his songs that he thought would be okay. I went to Escondido [in southern California] to learn them. We sat in his house and routined everything as much as we could, so that we didn’t go into the studio too raw. And it was great. We watched TV, we hung, we ate together. I got to know him then as well as I ever would.

You recently said you’d like people to tap in to what Cale did. If readers are intrigued by the new album and want to check out Cale’s music, what gets your vote for the best Cale album to start with?

Whoa, that’s a tough one. It’d be tempting to say the early stuff, like Naturally [1971] or Okie [1974]. But then you can come right up to date and get To Tulsa and Back [2004] too. I don’t think it matters, because it seems, in his middle period, anyway, that the songs on his albums didn’t necessarily come from the same time period.

I knew he had boxes of tapes, and when he wanted to put an album out he’d pick them at random, depending on what he wanted to get rid of. [laughs] But I’d say Naturally, and then whatever was close to the last. Guitar Man [1996] is great too.

Damian is Editor-in-Chief of Guitar World magazine. In past lives, he was GW’s managing editor and online managing editor. He's written liner notes for major-label releases, including Stevie Ray Vaughan's 'The Complete Epic Recordings Collection' (Sony Legacy) and has interviewed everyone from Yngwie Malmsteen to Kevin Bacon (with a few memorable Eric Clapton chats thrown into the mix). Damian, a former member of Brooklyn's The Gas House Gorillas, was the sole guitarist in Mister Neutron, a trio that toured the U.S. and released three albums. He now plays in two NYC-area bands.