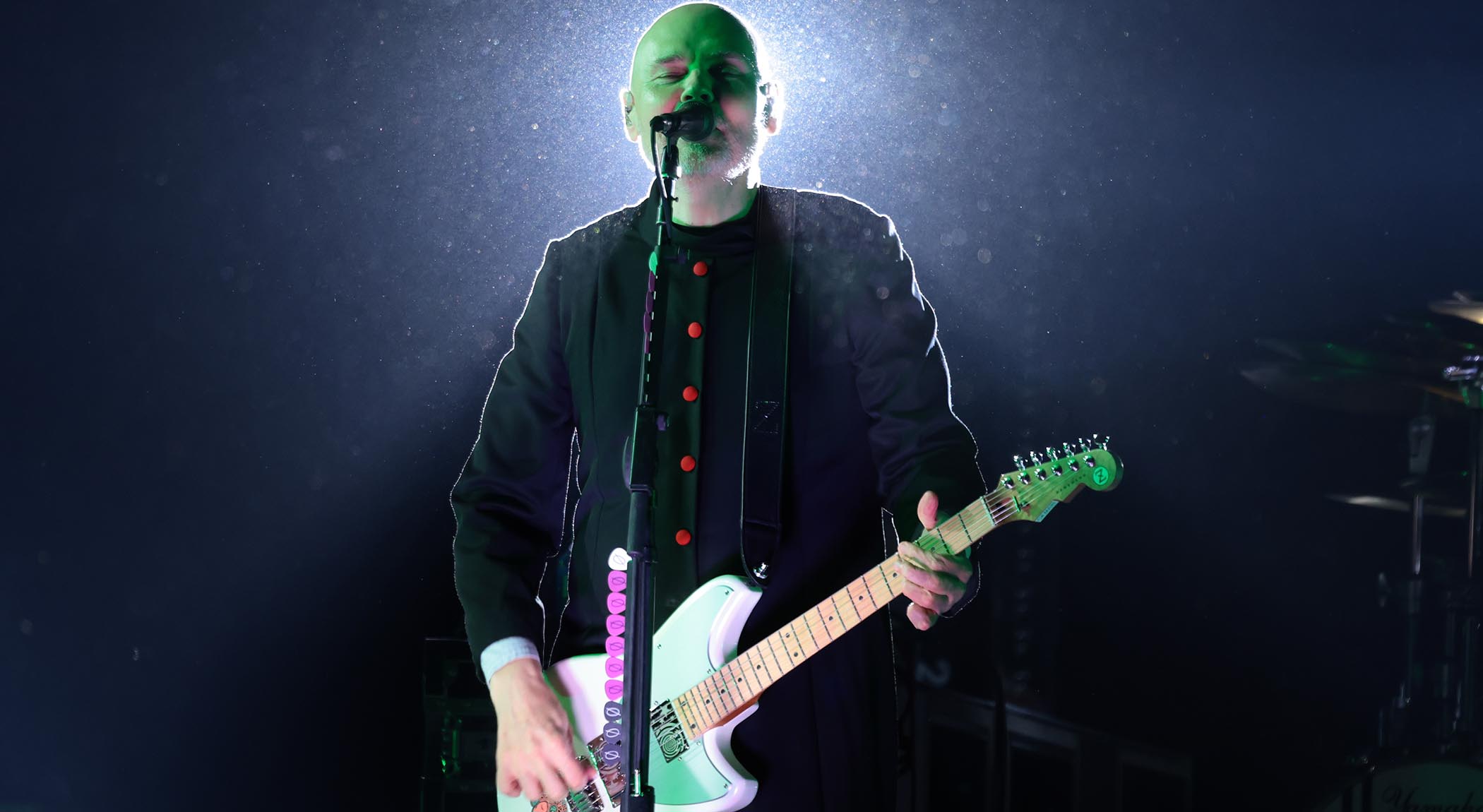

“I only picked up guitar in the first place to impress my father. I didn’t have a true desire to play that great players like Joe Bonamassa did”: Billy Corgan opens up on his guitar insecurities and being cast as the Smashing Pumpkins’ “big, bad Dracula”

On Aghori Mhori Mei, the Smashing Pumpkins recapture the vibe, feel and tones of their classic early ’90s LPs. Corgan explains how, why – and what took them so long

In case you haven’t been paying attention, everything Billy Corgan does or says has been making headlines lately. It comes with the territory of being in a mega band. And while that might sound somewhat frustrating, Corgan doesn’t think so.

“I’m at a point now where I don’t even care,” he tells Guitar World. “I don’t care what people think. I don’t care if they think I’m great; my focus is, I want people to enjoy the band. I want people to listen to our music and see us play.”

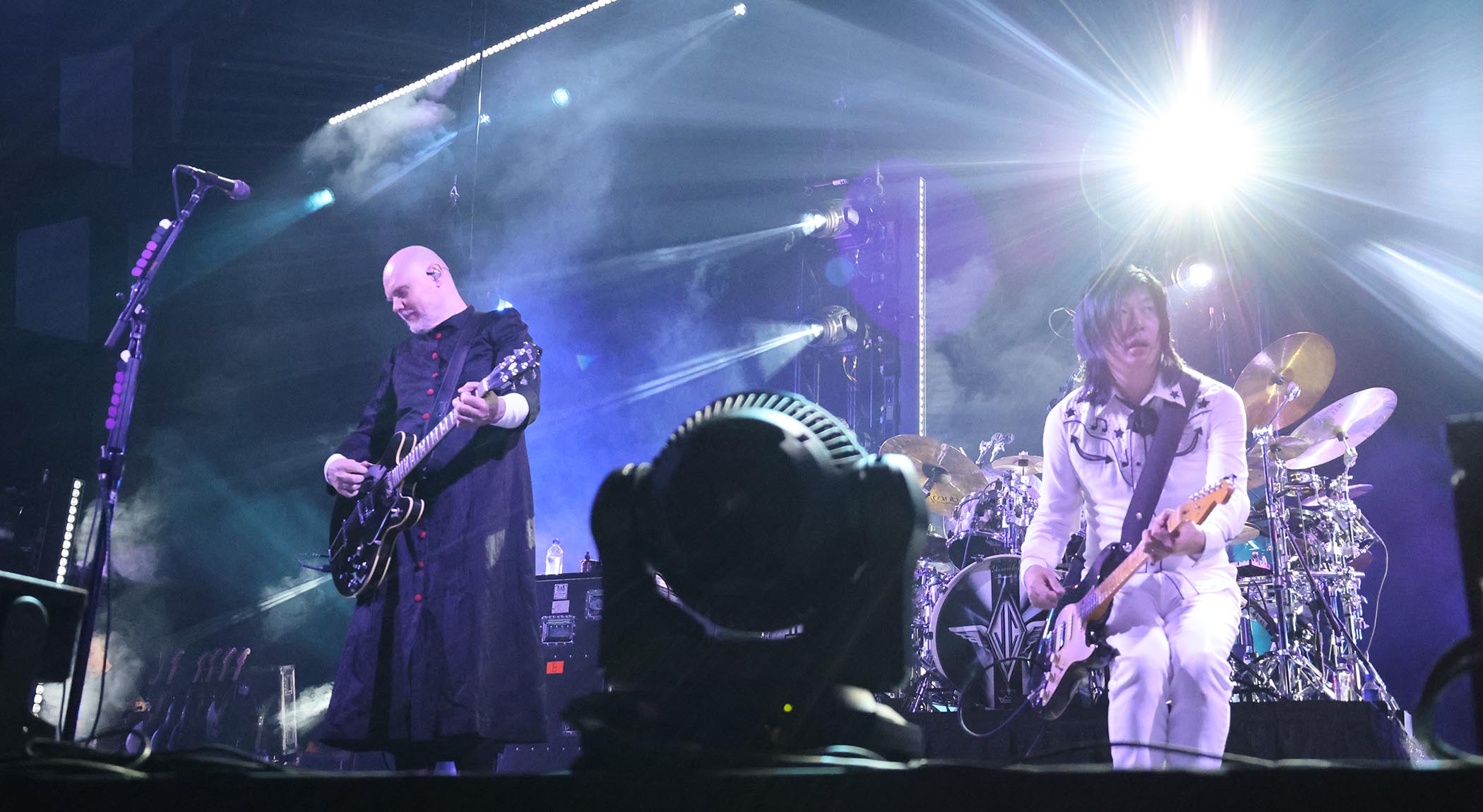

People have been coming to see the Pumpkins play. They’ve got a new shredder in guitarist Kiki Wong, who Corgan says has been “putting in the work,” and a new record in Aghori Mhori Mei, which harkens back to the Pumpkins’ iconic ’90s sound. But the metal-leaning (and also headline-making) Wong and a decidedly heavy record hasn’t stopped detractors.

“Our music has always gone from metal to alternative,” Corgan says. “It gave us an advantage, but it caused problems because metal was ‘stupid.’ If you played a solo, it had to be ironic. We didn’t give a shit about any of that; we just wanted to womp you over the head.”

Corgan still aims to womp, and he hopes the fans are up for it. But Aghori Mhori Mei isn’t a nostalgia trip. “Maybe it won’t sound like the music you wrote when you were 25,” Corgan says. “But there’s a lot of people who identify with the message because they see part of themselves in it.”

At 57, Corgan is forever underrated and perpetually used as clickbait. But he’s got a cache of iconic records, and despite the punches thrown, he’s still standing.

“I was the big bad Dracula who wouldn’t let his friends play in the sandbox,” Corgan says. “We were under tremendous pressure. We had a lot of success. Obviously, good or bad, our decisions that we’ve made have worked because we’re still talking about that music, right?”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

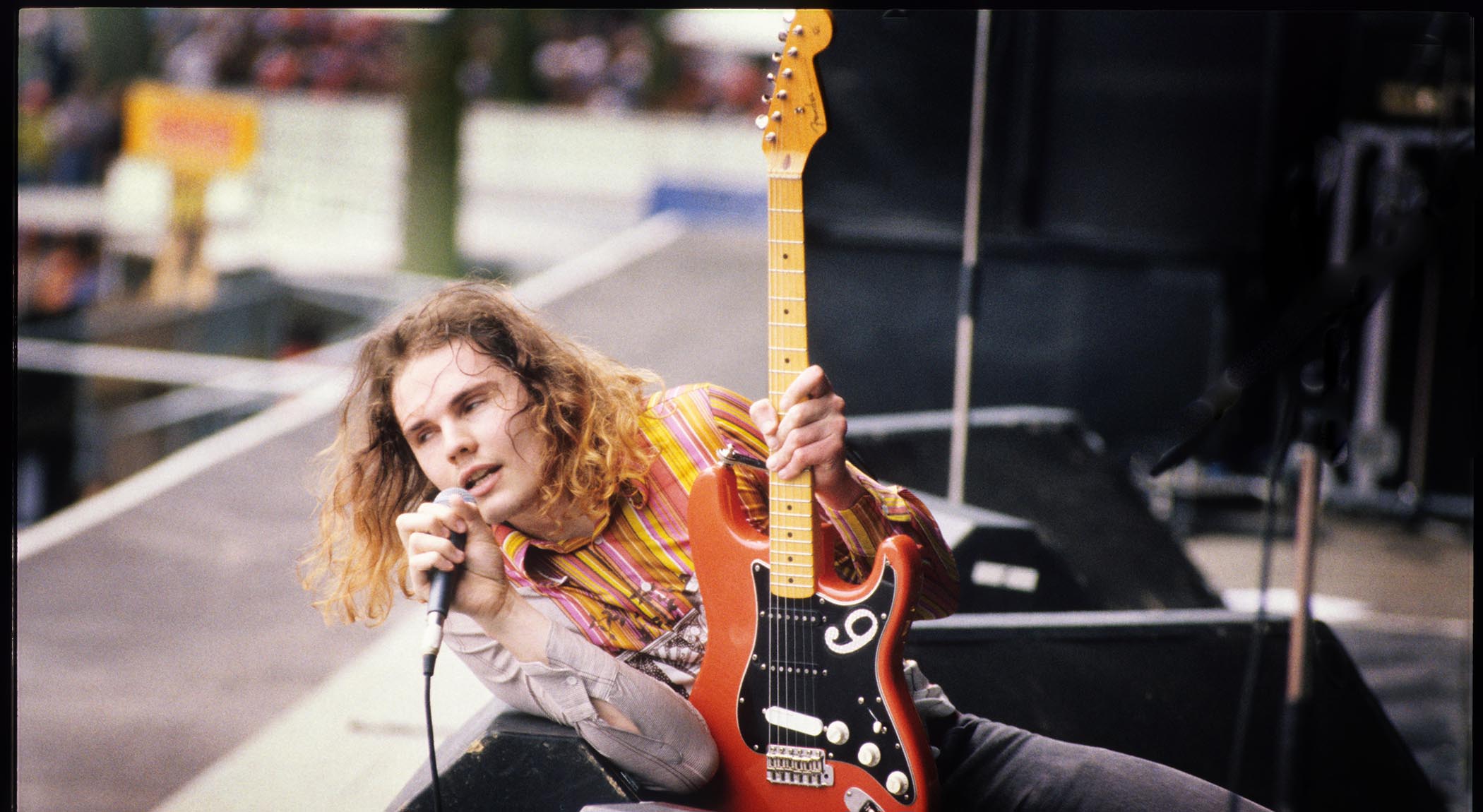

Right. While the Pumpkins’ last few electronic-leaning records didn’t capture imaginations quite like 1991’s Gish or 1993’s Siamese Dream, neither did 1998’s Adore. Corgan has seen this movie before – and he’s the leading man. But that doesn’t mean he’s okay with his pursuits being taken for granted.

“We should not be so blithe as to assume people who have made great musical contributions – just because they’re at a certain point in their life – are no longer capable,” he says.

“Artists are sensitive people. If they feel a vibe that people aren’t interested in, they think, ‘Why bother?’ I’ve just shut all that noise out. Trust me, I had people tell me, ‘We don’t care about your new music. We don’t care what you do. We’re just not interested. Please play Siamese Dream again.’

“That seems to have finally died away. It’s great; we want to make music for another 20 years if we can. You can judge us however you want; we’re an open book. But you’d be hard-pressed to look at us on stage right now and say, ‘That’s not a real band.’”

How did you avoid the nostalgia trap while putting together Aghori Mhori Mei?

“That’s a fantastic question. I’m not sure I can do it justice, but I’ll give it a quick try…”

I have a feeling you can.

“Thank you for that little bit of praise. When Jimmy [Chamberlin] and I had Zwan, our manager was Elliot Roberts, who famously managed Neil Young. Elliot had very strong opinions on nostalgia. He told us how nostalgia was the trap you could never escape from.

“He instilled in us that our future, if we had any future as musicians, would be navigating nostalgia. We stuck to our guns that it would work out, which was true. But there is another layer, if you want it…"

Hit me with it.

“Here’s the weird thing that you can never anticipate when you’re in your 20s making, let’s say, your seminal work that people will always identify you with. That’s when they get to know you, right? Whether it’s Drown in 1992, Cherub Rock in ’93, Bullet with Butterfly Wings in ’95 or Everlasting Gaze in 2000, you never imagine that someday, you’ll be answering to the shadow you created in your youth.”

You can never live up to that anyway because memory makes things seem grandiose.

“You’ll be standing on stage somewhere, or putting out a record years later, and the person in front of you, or sitting at home listening, has built an impression of you that’s not accurate. It’s accurate in their mind, and they expect you to live up to the accuracy of their impression.

“If I can be overly simplistic, the general impression of the fan is that this band is a guitar band that makes loud, alternative rock. Hence the, ‘Hey, are you the ‘rat in a cage’ [from Bullet with Butterfly Wings] guy?’”

Some would answer to that, but you don’t.

“It doesn’t matter. They have this impression in their mind of who you are. So, in a different generation, you’re expected to live up to the pressure of their impression. Not the reality – but the impression.

We decided – on our terms, in our own time, with a very organic feeling – that it was time to go back to this way of playing guitar and drums, and that we finally did what people wanted of us

“That impression extends down from the media to the fans to radio stations. It doesn’t take a genius to put a finger up in the wind and understand how the wind blows. And trust me – people will sit you down in boardrooms and say it nicely. Sometimes they won’t say it nicely.”

People assume how you might handle that. But how do you handle that?

“They tell you, ‘It’s in your best interest to make the music that is expected of you, not the music you feel.’ You can say, ’It’s never worked for anybody. Show me a band it’s truly worked for.’ I used to say that, and I was right. But in the last 10 years, you can see bands from Gen X that never changed their script, and it does work. But we did [go the other way] in the ’90s, and you kind of can’t go back so readily.”

Why have you dialed back to your ’90s sound with Aghori Mhori Mei?

“That’s why it’s so interesting about Aghori Mhori Mei; we decided – on our terms, in our own time, with a very organic feeling – that it was time to go back to this way of playing guitar and drums, and that we finally did what people wanted of us.

“You can see we’re being rewarded for it, which is great. But it wasn’t in our bones to become a Xerox of who we used to be, which gets down to questions of integrity, self-motivation and why we’re even in this band.”

People make assumptions; they’ll say, “Billy Corgan. He plugs a Strat with Lace Sensor pickups into a Big Muff, and off he goes.” But there must be more; otherwise, why carry on?

“It gets down to a personal thing: my father passed away two-and-a-half years ago; my father was my true idol. He was a really good guitar player; I learned a lot from watching him play. He explained a lot about how he saw music, and I absorbed a lot of that into my philosophical thinking.

“When my father passed away, this curious thing that happened – which anybody who has suffered loss can understand – where part of mourning is you feel things that you can only feel once you lose somebody. The thing that struck me – and I couldn’t have expected it in a million years – was I only picked up guitar in the first place to impress my father.”

So your initial reasons didn’t stem from traditional watershed musical moments.

I didn’t have a true desire to play guitar in the way that some great guitar players like Joe Bonamassa did. When I look at him or Billy Gibbons, I see pure guitar players

“I didn’t have a true desire to play guitar in the way that some great guitar players like Joe Bonamassa did. When I look at him or Billy Gibbons, I see pure guitar players; I’m not really a pure guitar player.”

Does that impact the way you view the instrument?

“I’ve had, at different times, a love/hate relationship with the guitar. I didn’t realize until after my father passed away that my father was the reason I wanted to play the guitar. Once he was gone, I thought, ‘Well, gee, do I still even want to play the guitar?’ Because he’s not here anymore to impress, it was a very subliminal recognition.

“It was nothing I’d ever considered. Once I let that run through me, I came out the other side, thinking, ‘Yeah, I still want to play the guitar. This is a great way to continue to honor my father. He gave me the gift of music and playing guitar.’ I got super-motivated to play; it was a strange thing I could never have anticipated, but that’s how I ended up here.”

I understand what you mean when you say you’re not a “pure guitar player,” but you’ve also written riffs and solos that defined a generation.

“Let’s go at it from a couple of different points of view. Most people don’t even recognize my contributions as a guitar player. They don’t even assume I’m the one playing a lot of the guitar.”

Which is crazy to think.

“Well, yes. And then, you have these silly lists that come out about the greatest guitar players; I usually don’t even make those lists. Or they’ll put me behind somebody who I could play circles around. I don’t mean to denigrate the person in front of me or the people in front of me, but come on, you know? I’m enough of a guitar player to know who’s a great guitar player.”

Dig into that for me.

“I’ve played on stage with George Lynch and Uli Jon Roth, two of the greatest guitar players in history. I sat for hours across from Eddie Van Halen at 5150 with my jaw open, watching Eddie play, OK? My father was a great guitar player. I’ve got no problem acknowledging some of the greatest guitar players ever. I would never even put myself in their company.”

EVH comparisons are futile, but there’s no denying you’re underrated.

“Once you go beyond, let’s call it ‘the Zakk Wyldes and Dimebag Darrells and the truly great Randy Rhoadses,’ there’s a lot of people who pretend to play guitar. I certainly have no problem believing I’m better than a lot of them. Originally, I was a guitar player. That’s all I wanted to be. I was sitting at home at 17 trying to play speed runs. I wanted to be Yngwie Malmsteen, Randy Rhoads and Eddie Van Halen.”

What changed that?

“I only became a singer because the guy in my first band told me, ‘I’m not singing your songs. If you want to write songs, you’ll have to sing.’ My father rolled his eyes at my singing because my voice was strange. As you can imagine, in those early days, people would plug their ears at my voice, saying, ‘Your voice is way too weird.’ I have a letter from a major record company in my attic saying, ‘This band will never sell records because this guy’s voice is too weird.’”

Tell that to Geddy Lee.

“I wish I could sing as good as Geddy or as high. [Laughs] But I went through this weird – and again, it goes back to my father – almost guilt stage in my development as a musician. As I started to understand that my true gift was in composition, production, lyrics and melody, I almost felt guilty because the guitar took a backseat.”

Again, I go back to the fact that your records are loaded with huge riffs, memorable solos and incredible tones.

“Over time, it’s balanced into what it is. I can be a guitar player when I need to. I can play a lead when I need to. But I’m not somebody who gets up every day and plays the guitar. I’m more likely to play the piano – and I’m totally cool with that. I wish I was a better guitar player than I am. I wish I’d put more time in than I did. But that’s not the way it worked out.”

Is that why people relegate you? Perceived lack of time put in?

“If I’m being frank about it – and maybe this isn’t the best way to do it – but if I’m being frank, people have a hard time understanding that as it pertains to the Smashing Pumpkins, I’m writing the songs, lyrics, melodies, arrangements and playing most of the complicated guitar. And that I’m capable of doing a solo on top of that. I think that’s hard for people to process.”

Why is that?

“I’m saying, ‘Yep, I am,’ and they don’t want to believe one person can do all those things. And a decision we made as a band early in our history, I’m talking before Gish, was not to tell people how we worked. I’ve told the story a few times where it was [producer] Butch Vig who said, ‘Why doesn’t this sound like the demos?’ I said, ‘I’m the one playing on the demos.’

“He said, ‘You’re playing bass, all the guitars and the lead?’ I said, ‘Yeah. I’m singing, too.’ Butch said, ‘I want that band,’ and I said, ‘Well, you’re gonna have to tell the other people in the band because they’re not gonna be happy.’ Butch sat the band down and said, ‘This is the way it’s going to be.’ They said, ‘Okay.’”

So people relegate you because they incorrectly feel you’ve relegated your bandmates?

“We knew that was going to be a problem. Eventually, when the story got out, it turned into this other thing: I was the evil guy who wasn’t letting my band play on the records. But somehow, in the process of all that, people understood I was doing most of the work on the records, but they didn’t want to give me credit. Somehow, that persists.”

Sure, you play most of the guitars on the records, but live, you and James Iha create unmistakable sounds. It’s inclusive in that way.

“Let me say something about my guitar mate, James. He and I started the band in my father’s bedroom that he used to sell drugs out of, okay? I can still see us in that bedroom in 1988. James had his Johnny Marr haircut and Fender Telecaster, and somehow, we developed this swirly sound that people call the ‘Pumpkins sound.’ When you hear us play live, you can acutely hear how the way James and I play guitars together has to do with the band’s success.”

Does the public’s perception of the Pumpkins bother you?

“It’s weird because I’m proud of the work that I’ve done. At the same time, you’ll never see me run around saying, ‘The other people didn’t contribute or have anything to do with the success,’ because they had everything to do with it. It’s weird; it is what it is.”

Speaking of the “Pumpkins sound,” as you assembled Aghori Mhori Mei, what were the keys to harnessing that tone?

“When I worked with Tony Iommi in around 1998, I had this epiphany. I was in the studio, and I’m five feet away watching Tony, and I’m looking at his gear, and he sounded like Tony Iommi no matter what amp you’ve got him on. For guitar players, you always go back to the attack. If you look at Eddie Van Halen or Uli Jon Roth’s attack, it’s really in the picking.”

Is gear important?

“The gear is important. But a lot of guitar players place too much stress on the gear and not enough on the pick attack. I think it’s just the way I play. I’ve been using these boutique Carsten amps in the studio, not exclusively, but predominantly. Brian Carstens, an amp builder out of Chicago, built me an amp called the Grace. We’ve since built another, the Empire, which is a metal-based amp.”

You’re still using real tube amps?

“We’re still moving air. Some of the guitar sounds you hear on the new record are us recording on one amp and then running it through the other amp and combining the two signals. I’d say 90 percent of this was straight into the amps, pure power.”

Do you still break out any of your old Strats?

“I’m using my signature Reverend models, the Z-One and the Drop Z. Those aren’t modded guitars; those are off-the-wall, stock guitars. I had a relationship with Joe Naylor, who used to own Reverend and now does development for them. They approached me about doing a signature guitar in 2016, and that guitar [the BC-1] won awards at NAMM.

“Later, they approached me and said, ‘We don’t want to change that guitar; it continues to sell. It does well for us. Can we do a different guitar? Is there anything you want?’ I said, ‘I’d like a guitar that captures my ’90s sound.’

“Joe and I worked on getting what I call the ‘Sabbath note,’ which is a lower octave when you play low riffs, but it’s in the pickup sound. It’s not something you get out of the amp. That guitar [Drop Z], which still has my Railhammer pickups, has been successful; that thing is just vicious, man.”

And you’ve got an album to be proud of. That must be satisfying.

“We’re very encouraged that people are supporting our new music. It’s been a hard case to make – in the music business for the last 10 years – that the band has a future as a recording act. Most of the energy has been focused on the live show because we can go out and sell tickets because of our catalog.”

But you’ve also made headlines letting people know you’re not relying on that catalog live.

“If I had one meeting, I’ve had one hundred where I had to sit in an office and tell people, ‘Look, if I can’t make new music, and I’m not engaged in new music, you’re never going to get me to play these old songs.’ Some people, when they hear that, lose their minds. I got a bunch of clickbait headlines because I dared to say, ‘If I don’t want to play an old song, I just don’t play it.’”

Can you shed light on what you meant?

“I have too much respect for the audience to fake my way through. That turned into, ‘He doesn’t want to play his old songs.’ That’s really stupid because I wrote them. I don’t want to play the songs I wrote. No. I don’t want to play songs I don’t emotionally connect with. I don’t want to turn into that type of artist in front of an audience.”

You want to play the old songs; it just needs to be organic.

“It’s like the reverse [of the headlines]. If you see me playing an old song, I want to play it and share my experience with the audience. That’s the most honorable thing I can think of. I wrote it, and here we are, years later, sharing it. It’s an amazing feeling. I mean… are you kidding me? But we live in this stupid clickbait world.”

So, what’s your outlook?

“If I can’t make new music that people believe in, I’m announcing to the world that I’m a shadow of my former self. I’m not psychologically strong enough to stand up and think, ‘Yeah, I used to be better.’ I don’t get that. Why are you still in the game if you don’t believe in who you are today? Do something else. I still believe in the band and the power of music.”

“When I see fans interacting with our current music, it means we’ve crossed the generational divide. I’m not overstating it – we’ve seen many bands go way past what people assumed was their due date. The next step for the music business to come into the 21st century is to accept that any artist will always be able to contribute culturally with new music.”

- Aghori Mhori Mei is out now via Martha's Music.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.