“We play three to four hours a night or more. I study in real time, 100 gigs a year. That's a great deal of practice”: Bob Weir's 6 principles of rhythm guitar

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At first glance, it might seem that Marlin Perkins should put rock rhythm guitar on the endangered species list. But on higher ground, it's easy to see there is a lot more rhythm guitar playing than most people think about.

Wah-wah guitar, simple strumming, power chords, and chunky R&B phrasing are just some of the family relations that papa Berry's Johnny B. Goode spawned.

The Seventies produced few if any guitar heroes from the rhythm side. The Sixties of Berry, Richards, Townsend, Lennon, and Hendrix still pave much of the most-traveled roads. And while new avenues are beginning to open up in the hands of Andy Summers, Andy Gill, and Buzzy Feiten, it's still too early to tell how much of a mark they'll make on the grand map of time.

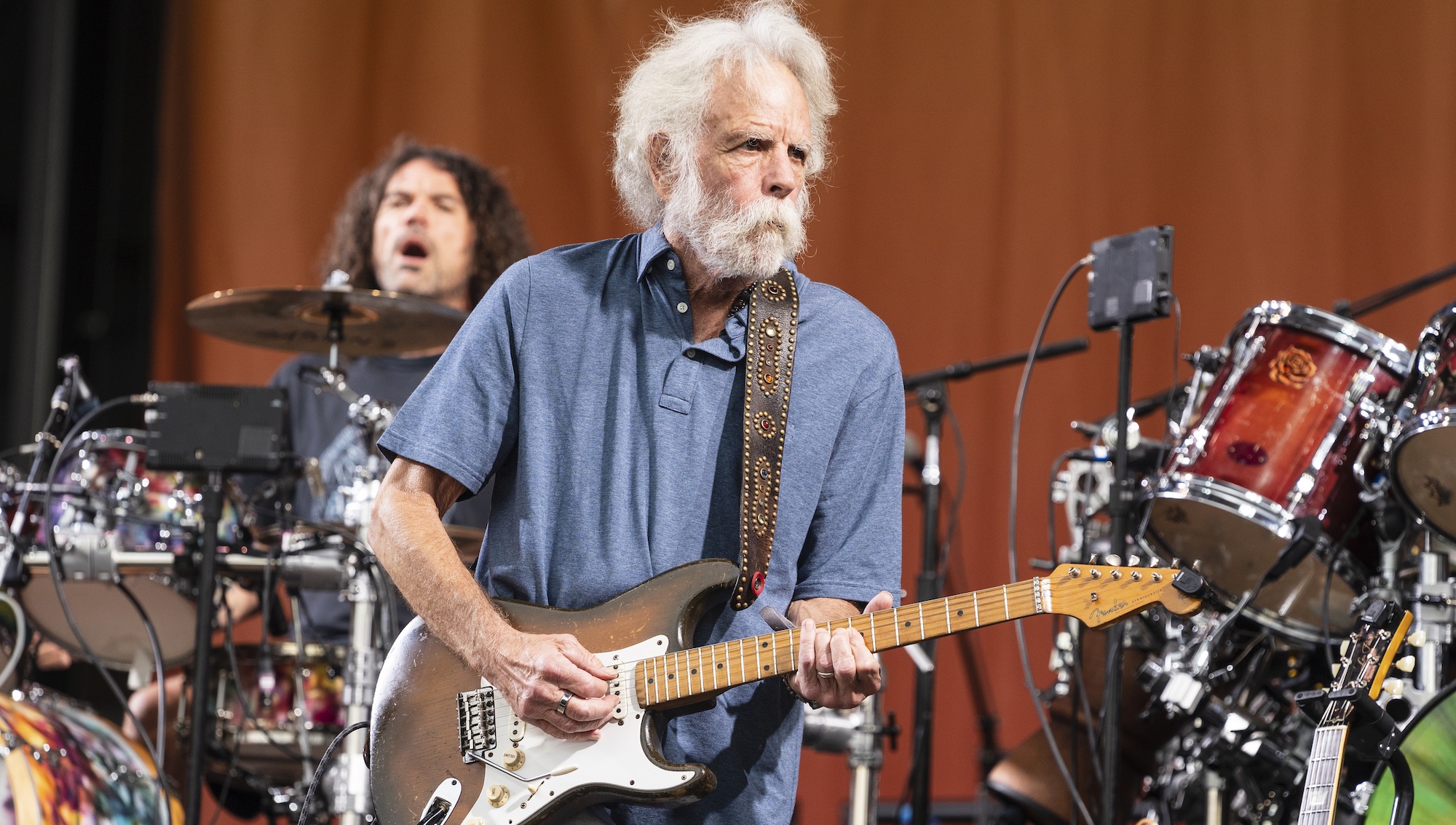

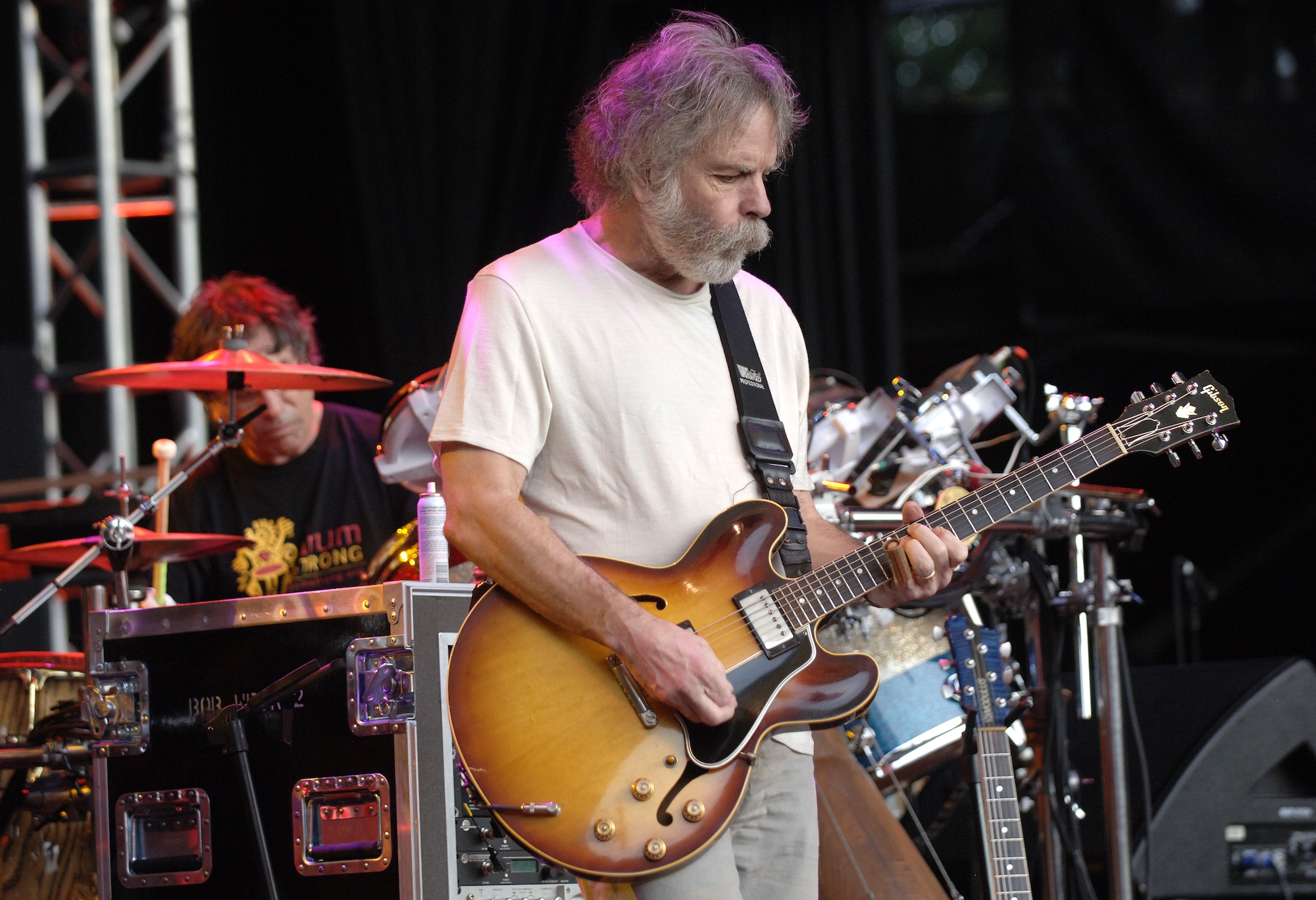

Article continues belowSince the mid-Sixties, the Grateful Dead's Bob Weir has been absorbing and redefining the subtle complexities that link the past to the future of rhythm guitar playing. His most recent insights are shared on [the 1981 album] Bobby & the Midnites.

Weir started by copying the guitar figures of Joan Baez and progressed onto the country blues of Reverend Gary Davis, who for a short time was his only “real” teacher. Today his ideas for rhythm guitar playing come from listening to pianist McCoy Tyner and string quartets.

Tapping those years of experience on stage and in the studio, Bob Weir offers the following insights into developing your skills as a rock rhythm guitar player.

1. Playing With The Band

“Gary Davis taught me how one guitar player could be a whole band. I've never applied this directly on stage. It's too complicated for a whole band to fall behind, especially a band with six members.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When you play with another guitarist or keyboard player, you're either going to dance around or walk all over each other. It's one or the other. So you have to play with other people you like and who will listen to you. And of course, you have to listen to them. Play long jams together, tape them, and find out who is good at what.

“If you're playing in a band, you have to get over the soloist ego hangup. You've got to listen to the whole sound. When you're first starting to learn, it's especially difficult to not sort of concentrate on what you yourself are doing. It's hard to step away from that and hear what the whole thing sounds like. The tape will do that for you. Go back and listen to see how everything fits together.

“You've got to listen for what a song needs. Even if you've got three guitarists in the band (remember Moby Grape?) at one point two of them have got to be comping behind the third one. They are going to have to work as one instrument.

“If you think of yourself as two lead guitarists working together, then suddenly you have a whole new different approach to rhythm guitar. You might play two or three notes and start thinking in terms of counterpoint. If you're thinking of three notes, you can start throwing in leading tones.”

2. On Developing A Part

“When you get close to a song it will tell you what kind of texture to play. Something that I like to do is try and be a horn or string section.

“For instance, on Sugar Magnolia, I'm a cross between a brass section and a guitar. I'm playing lots of triads punctuated by a line here and there and then another triad.

“There are two separate registers that I play off of. The alto register is the brass section and the baritone register is the guitar. It goes back and forth and I try and get a swing thing happening between the two.

“In this particular case the song developed because I was playing brass licks that I heard on a Delaney and Bonnie record. I was going for brass licks and whatever time I had in between was filled in with guitar. Then I thinned the whole situation down so it wouldn't be a big mess that nobody could play over.

“Once again, when you're playing in a six-piece band you have to be sparse and succinct to get through.”

3. On Strumming

“I use my whole hand to play the strings. I do brush strokes with the back of my nails and I pluck with the front.

“About seventy percent of the time I'm playing each note individually, either arpeggiating or plucking a chord all at once. Once you work up a touch for plucking a chord all at once, you have the ability to bring out a certain note within that chord. I use as many as four notes in a chord and I'll still be plucking it.

“I can bring out a certain note and create an ascending or descending line through a series of chords. I'm just playing the chords but there's that one note which sticks out. Besides a line, you can build the whole motion of the song just around that one idea.

“Again, if you listen to a tape of your band playing, you can find out if there's anyone else playing any of the notes in your inversion. If I'm playing an A chord and somebody else is playing my root, perhaps I'll build my inversion on the third or fifth of the chord. I might just leave out the note A, which is the simplest thing to do. And often times the simplest thing is the best.”

4. Time

“There's a wonderful little machine called the Trinome, which you can order from music stores. The Trinome will play polyrhythms. It has a bell and two clicks.

“Let's say you set the bells at one, one click at eight and the other at three. Then you have three against eight. If you want to learn seven, set the bell at one so it will signal every new bar. Set one click at seven and one at four.

“Times like three, five, six, and seven are not all that common in music but they're all real neat. Seven is a favorite of mine because you get the best of four and the best of three.”

5. Overtones

“Given the nature of electric instruments, there's often a fair bit of distortion involved. The nature of that distortion will generally supply additional notes of the chord you're playing.

“If you're playing the root and fifth and getting a lot of distortion and overtones, a subharmonic will supply the missing third of the chord. That's psycho-acoustics.

“Often times it's just the physics of acoustics. When you go to a root and sixth the subharmonic goes to a fourth below, which will also give you your chord. This is dense harmonic stuff, and given the nature of electric instruments, all of this is always happening anyway.”

6. Tone

“Timbre is real important. If your tone is too fat for a given section it's gonna make everything too thick. Of course if your tone is too thin for a section the whole thing will sound too thin. The rhythm guitar in this regard is very important. In terms of texture for the whole song, it's the most important instrument in the band.

“As everybody knows, guitarists get tired of one sound and go to another. If you start out, as I did, with double-coil pickups, you almost necessarily end up playing a single-coil pickup guitar. Then in another six or seven years you'll probably go back to the double-coil sound.”

Weir is currently playing his own autograph model Ibanez guitar with a coil-tapped humbucker in the bridge position and two single-coil pickups in the middle and neck spots.

He describes his amp setup as being a “huge montage of things.” Weir is thinking of asking Peavey to make him a compact system. He puts all of these elements into practice when the band's on stage.

Summing it all up for Guitar World he said, “Things are going to emerge under fire. That way you know damn well they're going to work. We play three to four hours a night, sometimes more. I study in real time, 100 gigs a year. That comes out to be a great deal of practice.”

- This article first appeared in the May 1982 issue of Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Grateful Dead [4K Remaster] Sugar Magnolia - Winterland 1974 [Pro Shot] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/FkmtOGAsCmE/maxresdefault.jpg)