“You look at everyone who’s ever stood in front of a band playing guitar and it all traces back to one man”: How T-Bone Walker invented electric blues guitar

T-Bone Walker may have been the first true hero of modern electric blues, but he stood upon the shoulders of jazz and blues giants

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let’s begin with a simple fact: T-Bone Walker wrote the dictionary on electric blues guitar practically single-handedly.

The licks and techniques he invented – or, at the very least, popularised – are still heard in almost every amplified blues guitar solo, whether said soloist knows it or not. Listen to Jimi, Eric, SRV, BB or Bonamassa for more than a few seconds and you will hear something T-Bone played way back in the 1940s.

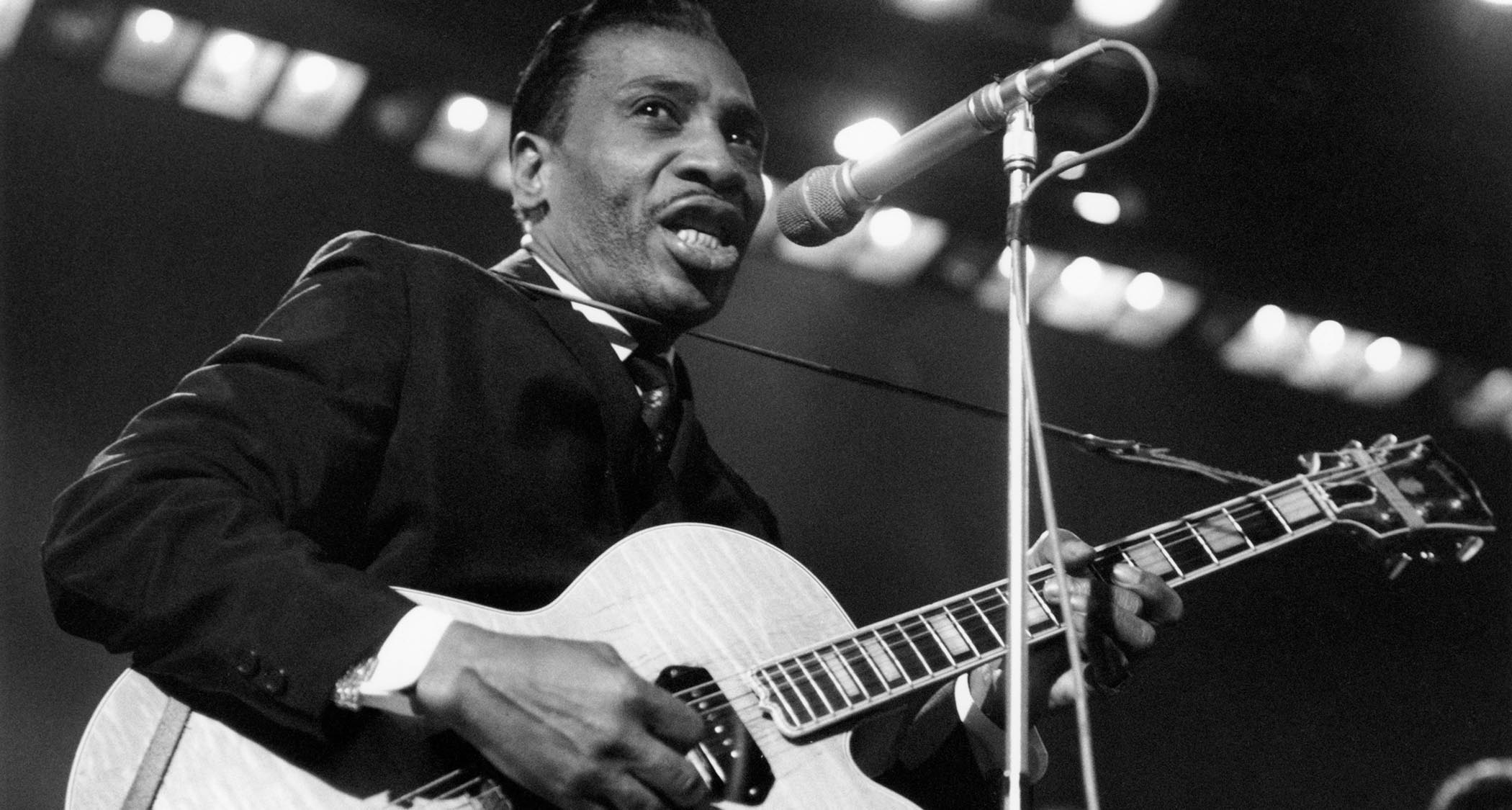

This revolutionary electric guitarist was the one that took the instrument, which was still in its infancy, to a place it had never been and would never return to.

Article continues belowIt was a place previously dominated only by horn soloists – at the front of the band wailing over the rhythm section and the brass riffs. Along with jazz genius Charlie Christian, T-Bone scared the hell out of the trumpet and saxophone stars. Their time was almost over, and within a decade they were the ones backing the guitar solos.

T-Bone Walker was the cutting edge of a coming-of-age for the guitar, the effects of which are still being felt today.

By the time of Walker’s peak in the late 1940s and early 50s, most blues guitarists were plugging it in and turning it up. So what made T-Bone Walker special?

After all, hadn’t performers of equal stature such as Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker both ‘gone electric’ by then? Yes, but T-Bone’s guitar was new – brand-new.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Waters and Hooker were, arguably, still speaking the same Delta-based language that had made them famous, and this time round they were merely louder. T-Bone’s guitar playing was as modern as the electric guitar itself. And it was as if he needed the electric guitar and the electric guitar needed him. They were made for each other.

At times, his guitar borrows more from the language of a saxophone than it does a guitar. His concept and phrasing drew from jazz in a way that the work of other blues musicians didn’t. That’s what made it sound fresh then and, indeed, now.

His solos bounce and swing like jazz, but they’re still the deepest and most authentic blues. Nothing like it had been heard before. It was, quite simply, the most forward-thinking development in blues since its inception.

The guitar itself seemed to undergo a series of musical identity crises in the first third of the 20th century. As jazz groups became larger it was too quiet to compete and found itself relegated to a role as a purely rhythm instrument. Here, it spent many a year thrashing out chords, four beats to the bar, alongside the upright bass and drums.

By the 1920s and 30s, many jazz and pop guitarists abandoned the guitar in favour of the banjo – a much louder instrument. For the early blues players it fared better as it was used almost exclusively as the sole accompaniment for a vocalist and could therefore be heard.

Another musical strand was the hugely popular Hawaiian style, which eventually birthed the Dobro, National, and lap and pedal steel variations on the traditional or ’Spanish’ guitar.

It certainly seemed like it would never be able to hold its own out front. But, eventually, microphones connected to primitive PA systems were used to boost the guitar’s volume – and this, in turn, led to the development of a dedicated system for amplifying them.

Initially, the first ‘real’ electric guitars were amplified Hawaiian steel guitars. But we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves… because without the musical foresight of certain acoustic players, there may not have ever been a need for the electric guitar, and we may not have had T-Bone Walker as a result.

For everything from classical to folk, blues and country music, the acoustic guitar was all that was needed. Many pop and jazz guitarists used something akin to the Gibson L-5, a large-bodied acoustic archtop that produced enough volume for most settings, albeit rarely as a solo instrument. Archtop design hasn’t, in the many years that have passed since, managed to improve much on the initial design of the L-5.

Other jazz musicians settled on the banjo, which could cut through a loud frontline of trumpet, trombone and clarinet with relative ease. Meanwhile, blues artists tended to work solo with the guitar as accompaniment to a vocalist – often themselves – and would only have to compete with a pianist, at most.

It’s really for the benefit of a single-string soloist in front of a band that the guitar amp finds its place, and there are a few pioneers that we need to thank for bringing the guitar out of the rhythm section and into the spotlight.

Arguably the first true guitar-hero in the modern sense was Nick Lucas, with titles such as Teasing The Frets and Picking The Guitar going back to the very early 20s. Jazzman Johnny St Cyr waxed several short solo passages in the mid-20s as part of Louis Armstrong’s revolutionary Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings.

But, arguably, it’s the quite incredible set of records made by Eddie Lang and Lonnie Johnson in 1928 and early ’29 that really opened the door for a generation of six-string soloists. Both of these musicians were stars in their own right, working in a variety of settings, but it’s with these handful of recordings that their guitar prowess caused such a radical stir.

Other names were gradually changing the general perception of the instrument as the 1930s dawned. Guitarists such as Teddy Bunn, Carl Kress, Dick McDonough, Eddie Durham and, of course, Django Reinhardt were proving that six strings could deliver just as much expression as the best horn players of the day could.

However, with the exception of Lonnie Johnson, none of these were dedicated bluesmen. It was in the world of jazz that the guitar as a single-note solo voice seemed to be making leaps and bounds. In the blues world, the guitar was in danger of being left behind.

Taking The Lead

It was the Rickenbacker company that produced the first commercially available electric guitars with its now-legendary lap steel ‘Frying Pan’ appearing in 1932, meaning that the first electric players were indeed from the Hawaiian school of playing.

Despite Rickenbacker being innovative and pioneering, it was the appearance of the Gibson ES-150 in 1936 that really set the wheels in motion for the electric guitar

Next, the Electro-Spanish Ken Roberts model from 1935 was the first guitar with a 25.5-inch scale and, incredibly, even featured an early incarnation of the vibrato arm. It’s hard to see what it was designed for in those early days, other than to maintain a loose connection to Hawaiian style, but it was certainly one of the world’s first whammy bars.

However, despite Rickenbacker being innovative and pioneering, it was the appearance of the Gibson ES-150 in 1936 that really set the wheels in motion for the electric guitar, changing music history at the same time.

‘ES’ stood for Electric Spanish; there was still a need to distinguish between a ‘regular’ guitar (or Spanish) and a Hawaiian (or slide guitar). The ‘150’ was the price, in dollars, for the full guitar, cable and amp package. That’s about $3,500 in today’s money.

This is the guitar that history remembers as the model that sported the ‘Charlie Christian’ single-coil pickup, designed by Gibson employee Walt Fuller.

![T Bone Walker (with Dizzy Gillespie's Band) - 'Woman You Must Be Crazy' live [Colourised] 1966 - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/MnsxljZfZiE/maxresdefault.jpg)

As the jazz giant that he was, it was Christian himself who helped popularise the instrument before his tragic death at the age of just 25 in 1942 – incidentally, the year of T-Bone Walker’s first electric recordings. The ES-150 was also the precursor to the ES-250, which appeared at the tail end of the 1930s and was Walker’s main guitar for the next decade.

As for early electric blues recordings, many have claimed Bennie Moten’s 1929 Every Day Blues with Eddie Durham on guitar as the first electric blues guitar record.

It’s a fantastic record, but it isn’t blues, and also the guitar resembles a mic’d-up Resonator, rather than an actual electric. Another Durham offering is 1935’s Hittin’ The Bottle, which also sounds like a mic’d acoustic over a chord sequence that isn’t blues.

One early recording that is authentic blues is Andy Kirk’s 1939 track Floyd’s Guitar Blues, which features Floyd Smith playing very horn-like phrases in the Hawaiian style on what could therefore be a lap steel.

Another cut from a few years earlier in 1937 is Blue Guitars, recorded by the Western swing group The Light Crust Doughboys with Zeke Campbell playing an early electric blues solo. Big Bill Broonzy’s 1938 track It’s A Low Down Dirty Shame features a 16-year-old George Barnes, a future jazz star, playing electric blues guitar.

In 1942, by the time T-Bone had recorded his own electric for the first time, there had been several sides produced featuring the new-fangled instrument in a blues setting. But, important as these records are, none display the swagger of T-Bone’s playing or the depth of his connection to the blues. In fact, none even get close.

One early recording that is authentic blues is Andy Kirk’s 1939 track Floyd’s Guitar Blues, which features Floyd Smith playing very horn-like phrases in the Hawaiian style on what could therefore be a lap steel.

Another cut from a few years earlier in 1937 is Blue Guitars, recorded by the Western swing group The Light Crust Doughboys with Zeke Campbell playing an early electric blues solo. Big Bill Broonzy’s 1938 track It’s A Low Down Dirty Shame features a 16-year-old George Barnes, a future jazz star, playing electric blues guitar.

In 1942, by the time T-Bone had recorded his own electric for the first time, there had been several sides produced featuring the new-fangled instrument in a blues setting. But, important as these records are, none display the swagger of T-Bone’s playing or the depth of his connection to the blues. In fact, none even get close.

True Electric Blues

All this is to make the point that T-Bone Walker was not just a pioneer; he was unique, and remains so, too.

T-Bone Walker took blues out of the country and into the city, and made it jump and swing

There was nobody else around at that time who sounded like him. Blues in the mid- to late 30s was still very much an acoustic Delta-based idiom performed by the likes of Charley Patton, Son House, Big Bill Broonzy, Robert Johnson and Bukka White.

T-Bone Walker took blues out of the country and into the city, and made it jump and swing. From this perspective, he owes more to blues-influenced jazz artists such as Count Basie than he does to the Delta.

The secret to T-Bone’s individuality is perhaps owed to combining the sophisticated swing of the big bands of the day – Basie, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Jimmy Lunceford et al – with raw, pure blues. Here, he created something completely brand-new that evolved through the 40s into the rhythm and blues revolution that, in turn, gave the world rock ’n’ roll.

T-Bone was now alongside other R&B stars such as Louis Jordan, Joe Turner and Wynonie Harris, but Walker was the only frontman during this period that was also a guitarist; the others were sax players or vocalists. Also, many of the early rock ’n’ roll stars such as Fats Domino, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis were pianists.

T-Bone’s position as the number-one blues guitarist went unchallenged throughout the 1940s until the mid-50s when an explosion took place that produced the likes of BB King, Elmore James, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson and Hubert Sumlin, alongside country-influenced rockers such as Scotty Moore and Chuck Berry.

Even today, T-Bone’s influence is still wholeheartedly felt, despite his importance sometimes being overlooked

Within just a handful of years, the impact that Walker had over the evolution of the electric guitar had spawned the first wave of rock guitarists.

The young Becks, Pages and Claptons would have seen T-Bone on the hugely successful Folk & Blues Revival shows that toured Europe throughout the 60s bringing T-Bone, now in his role as elder statesman, to new audiences eager to discover the roots of rock.

Even today, T-Bone’s influence is still wholeheartedly felt, despite his importance sometimes being overlooked. As fellow Texan Jimmie Vaughan said: “You look at everyone who’s ever stood in front of a band playing guitar and it all traces back to one man. It’s impossible to spend an hour in a blues club and not hear dozens of T-Bone’s inventions.”

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

Denny Ilett has been a professional guitarist, bandleader, teacher and writer for nearly 40 years. Specializing in Jazz and Blues, Denny has played all over the world with New Orleans artist Lillian Boutté. Also an experienced teacher, Denny regularly contributes to JTC and Guitarist magazine and is founder of the Electric Lady Big Band, a 16-piece ensemble playing new arrangements of the music of Jimi Hendrix. Denny has also worked with funk maestro Pee Wee Ellis and is the co-founder of Bristol Jazz & Blues festival.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.