“He used to call himself the worst bass player in the business, but he knew that wasn’t true”: The life (and tragically early death) of Phil Lynott, Thin Lizzy’s legendary bass-playing frontman

Phil Lynott was a troubled genius who rose from a tough background to take his place in the pantheon of rock gods

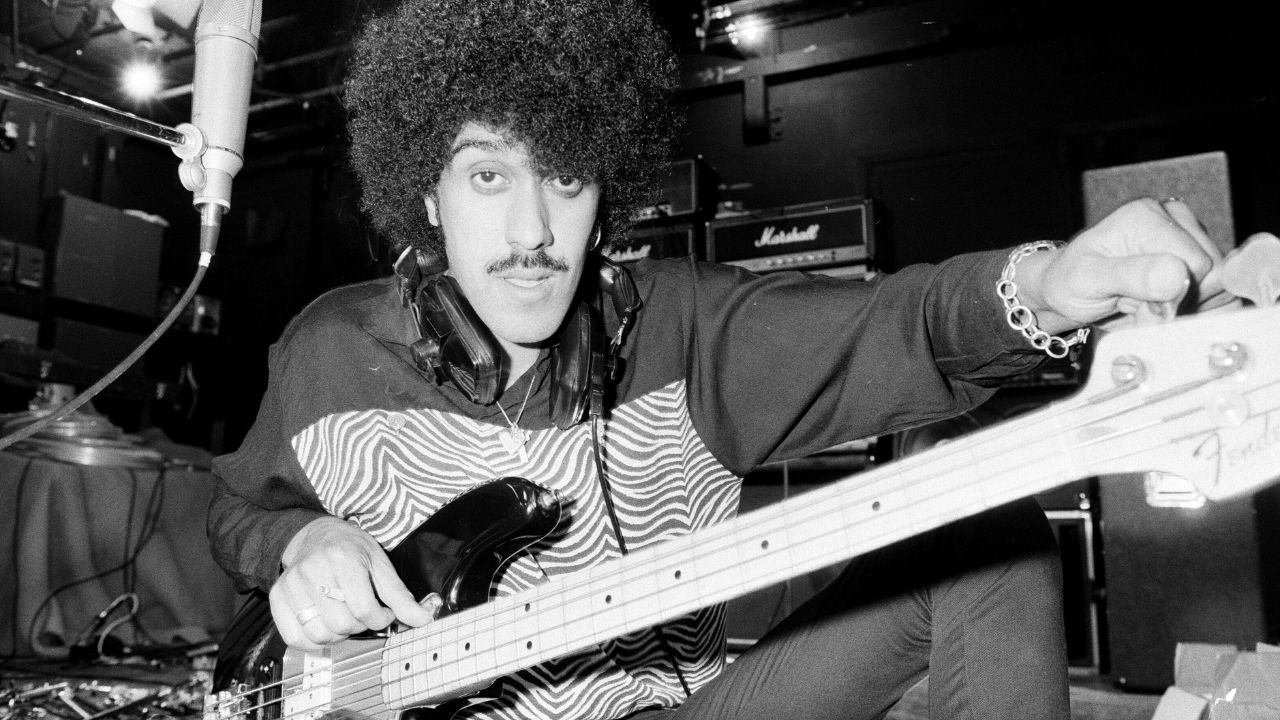

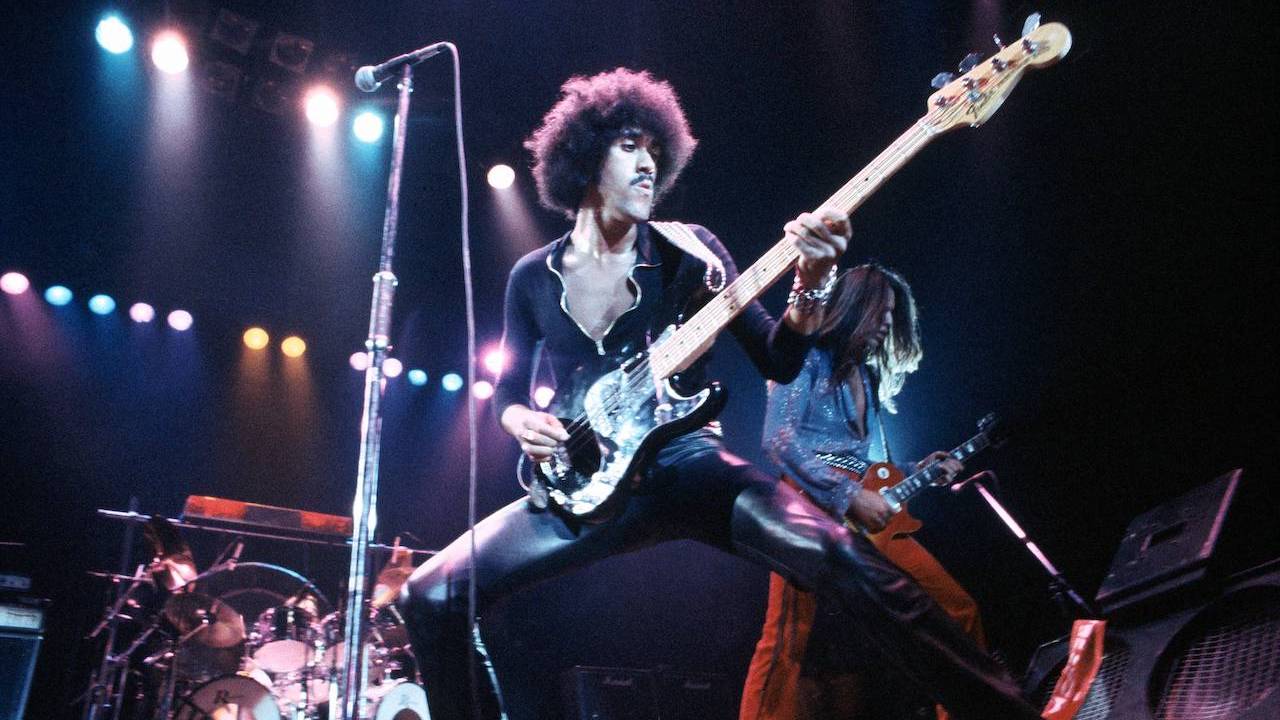

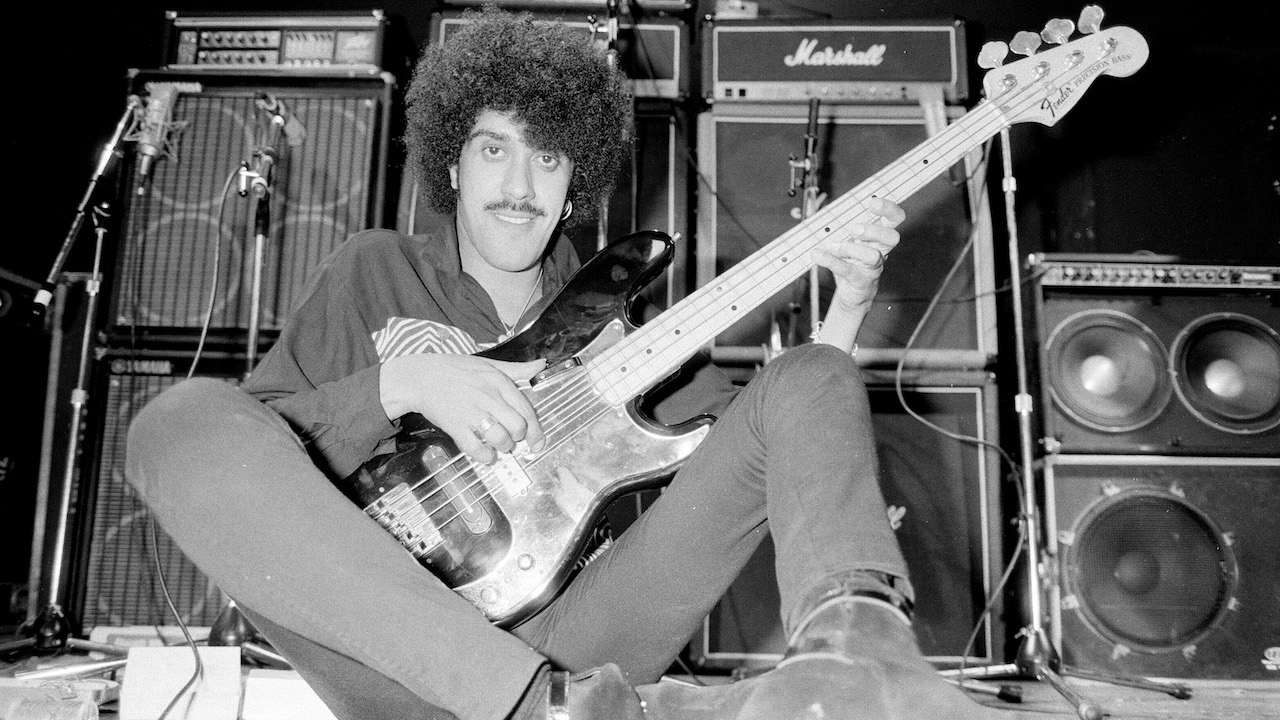

Bassist Phil Lynott was one of a kind. If you're old enough to remember rock music in the 1970s and early ’80s, you might recall seeing him on TV or playing live, knocking out riff after riff – often on an iconic black Fender Precision Bass with a mirrored scratchplate.

“Phil was a big entertainer onstage,” said Thin Lizzy guitarist Scott Gorham. “He used to joke around and call himself the worst bass player in the business, but he knew that wasn’t true.

“I’ve played with several Class A bass players and each one was amazed at what Phil could do, in terms of the notes he picked out, the strength with which he hit the strings and how he kept the groove going, while singing all of the time.”

Whether or not you're familiar with Lynott's work, you'll have benefited from his career – because the music he made influenced many of today's rockers and, perhaps more importantly, demonstrated that if he could make it, anyone could.

Lynott's background was straight from the school of hard knocks. He was born in 1949 in West Bromwich, the son of a black Brazilian father, Cecil Parris, and a white Irish mother, Philomena Lynott.

His father scarpered back to Brazil when Lynott was only three weeks old, leaving the boy with his mother's surname and an upbringing in a variety of deprived areas, including Moss Side in Manchester and then Crumlin in Dublin.

Lynott began singing in a band called The Black Eagles in the middle of the 1960s: as he later recalled, “There were two ways of making it back in Crumlin. You were either a tough guy who thumped everybody around and pulled the chicks that way, or you played in a band.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Not wanting the bruises, and being a bit of a coward at heart, I decided to sing in a band. It's the ultimate ego trip to jump up on a stage in front of thousands of people and say, ‘Listen to what I have to say.’”

Moving to Skid Row and taking up the bass guitar, Lynott began to establish a stage persona. Growing a large Afro, dressing in a range of stage gear that varied from military to piratical and all stages in between, he played his Precision at waist height and evolved an instantly recognisable look.

As a bass player Lynott developed fast. Always more extravagant as a songwriter and singer than a bassist – his basslines were solid and heavy rather than flashy – he specialised in a warm, middle-heavy tone that perfectly anchored his fellow guitarists’ playing.

This came to the fore with Thin Lizzy, which he formed with drummer Brian Downey and Eric Bell (the first of a succession of guitarists) in 1970. Three albums were released by this lineup before a spectacular, and wholly unexpected, hit with a version of the old Irish jig Whiskey In The Jar. Gallingly for us, it featured no bass – but this didn't stop it becoming an enormous hit.

After Bell was dismissed through ill-health and his successor Gary Moore – who went on to serious fame and fortune himself – left after a few months to join Colosseum II, Lizzy maintained a fantastic level of success until the end of the 1970s, when the wheel of musical fashion began to change at a perceptible rate.

Before any of that, the band's best-known album Jailbreak became one of the must-have albums from the last days of rock, released just before punk exploded into the public consciousness.

On the album’s quintessential track The Boys Are Back In Town, Lynott confines himself to root notes, driving the song through the verses and providing an expert, almost funky bassline.

Oh, and while we're talking late-’70s Thin Lizzy, you'll probably be familiar with the sleeve of 1978's Live And Dangerous, too – with its still-gobsmacking close-up of Lynott, down on his knees on stage in ecstasy, Fender Precision raised as if in supplication to the gods of rock.

Another much-loved Lizzy tune, Jailbreak, opened the Live and Dangerous album, and with good reason. Lynott’s bass is mixed high enough for his grasp of the role of the bass in the onstage dynamic to reveal itself perfectly.

Although Thin Lizzy had always functioned alongside new music rather than in conflict with it – Lynott and other members of the band played in a one-off act called The Greedies in 1978 alongside Sex Pistols Steve Jones and Paul Cook, for example – by the 1980s the post-punk, electro and new wave scenes were dominating the charts, and the balls-out rock which had typified so much of the previous decade was beginning to seem a little outdated.

Had they but known it, rock of this style was destined to remain relatively uncommercial until the late 1990s, when it was rebranded ‘classic rock’ and found a whole new fanbase. Perhaps this was a factor in Lynott's decision to embark on a solo career in parallel with Lizzy, releasing Solo In Soho in 1980.

The highlight of the album for many was King's Call, a tribute to the recently deceased Elvis Presley which featured Mark Knopfler on guitar.

Thin Lizzy finally split in September 1983 and Lynott was free to embark on a full-time solo career, but unfortunately he had developed a powerful drug and alcohol habit, which began to affect his health.

Despite this, he still guested on three successful singles before his substance problems went too far: Out In The Fields and Parisienne Walkways with his old sparring partner Gary Moore, and another with Roy Wood called We Are The Boys (Who Make All The Noise).

In 1984 Lynott formed a new band, Grand Slam, but faced some scepticism from the British press about how well it could be expected to perform in the wake of the unmatchable Thin Lizzy.

Before he could prove his detractors wrong, however, his struggle with stimulants caught up with him and he was admitted to hospital on Christmas Day, 1985. He died of heart failure and pneumonia 10 days later, aged only 36.

The legacy of Lynott is effectively synonymous with that of Thin Lizzy, as it was so often a vehicle for the songs he wrote: he often said that the job of the guitarists who passed through the band was to ‘interpret’ his songs in their own way.

Lynott paved the way for the singer/bassist in rock music, with perhaps Brian Wilson, Paul McCartney and Jack Bruce his only real predecessors in that sense.

He also, of course, did much to establish the legitimacy in the eyes of the white rock audience of Black musicians, delivering a set of songs that have endured for five decades and counting.

The regular pilgrimages made by Lizzy fans to Lynott's grave at St. Fintan's cemetery in Sutton, and to the statue of him which was unveiled on Harry Street, next to Grafton Street in Dublin, in 2005, are testimonies to his popularity.

As for we bassists, who worshipped him for his songs and his bass playing in equal measure, remember his famous words: “I only want to be successful for what we are, rather than for what people want us to be.”

Wise words for bass players – as for everyone else.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Gary Moore feat. Phil Lynott - Out In The Fields [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/VbUiKj9DML4/maxresdefault.jpg)