How a capo can make 5 classic songs easier to play

From Eagles' Desperado to Aerosmith's Dream On: here's how a capo can make playing these hits simpler than ever

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's a view held by some older, formally schooled guitarists that “you shouldn’t ever have to ‘cheat’ by using a capo and should be able to form any chord shape with your fingers.”

Well, this older, formally schooled guitarist thinks that’s nonsense. It’s just foolish pride talking and ultimately a self-defeating notion that limits the possibilities of what you can play and the sounds you can create on your instrument, and it’s comparable to another dumb, dogmatic rule that says “you shouldn’t have to rely on altered tunings and should be able to play anything in standard tuning.”

Yeah, right. Tell that to a highly original and innovative songwriter like Joni Mitchell who has made a brilliant career using open tunings! It’s like a carpenter declaring, “you shouldn’t have to rely on a nail gun, cordless drill or table saw when you have a perfectly good hammer, screwdriver and handsaw.”

Yes, you could in some cases manage to get the job done rather arduously without the aid of these labor-saving tools, but why make things more difficult and limit yourself?

By not having to commit your index finger to the task of barring, you're now able to perform gracefully elegant, decorative, James Taylor-style melodic embellishments

The capo is a marvelous invention, one that offers the player of a stringed instrument a movable, finger-free barre across the strings at any given fret and thus the ability to take advantage of open strings, relative to the capo, and finger-friendly, non-barre open chord shapes and voicings – those so-called “cowboy” chords.

Players can do so in just about any key, as determined by where you place the capo on the fretboard, which is a huge plus for accommodating a vocalist’s optimal singing range.

And by not having to commit your index finger to the task of barring, which in many cases limits and handicaps your fret hand’s potential for movement, and instead being able to form chords with just your fingertips, you’re now able to perform gracefully elegant, decorative, James Taylor-style melodic embellishments – what I call open-chord “extensions” – to major, minor and 7th chord voicings, such as sus2s, sus4s and add6s, typically performed with hammer-ons and pull-offs, and have all the moving and held notes ring together.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

An added benefit of using a capo is that, depending on how low your guitar’s action is at the nut, meaning how low the individual saddles are cut, the capo can instantly lower the action at that end of the neck.

Most guitars are set up with the string height at the nut to be higher than a “zero fret,” and so the lower action afforded by the capo helps make all those previously mentioned open-chord extensions, hammer-ons and pull- offs, as well as barre chords, noticeably easier to finger, which is a much-welcomed benefit.

It also makes for more precise intonation, as there’s less of the unwanted pitch sharpening that can occur when you press a string down next to a nut that’s cut rather high.

Perhaps this is why a lot of singer-songwriters subconsciously love using a capo.

There have been many different capo designs invented over the years, ever since the early 20th century, when poor but resourceful blues and folk guitarists would fashion one out of a pencil and a rubber band.

The capo is essentially a clamp, but there are other considerations to take into account. These include how quickly and conveniently it can be deployed and removed, and the degree and evenness of tension across the strings.

The latter is very important because you don’t want the capo to apply more pressure against some strings than others, as that can cause them to go noticeably sharp and out of tune, as happens if you squeeze a string harder than normal when fretting.

And you don’t want strings to buzz either, from not being pressed down against the fret firmly enough.

I’ve tried using many different capos over the years and came to the conclusion a while back that the Kyser Quick Change capo is the most reliable, well-built and convenient one to use when performing live, which I do 150 nights a year, on average. (By the way, congratulations to Kyser, as they, like Guitar World, celebrate their 40th anniversary this year!)

On a regular acoustic guitar, usually the highest you can place a capo is the 9th fret, due to that instrument’s typically massive neck heel

What I love about this capo’s design is that I can quickly grab and squeeze its handlebars, which stick out above the neck, where I can clearly see them in the heat of battle onstage, and relocate it from my guitar’s fretboard to the tip of its headstock, where it can be temporarily parked for ready access when I need it again, which is often.

I mostly play electric guitar onstage, a Gibson SG Standard, strung with a set of .011’s and equipped with a Fishman PowerBridge piezo transducer, which gives me an amazingly authentic acoustic guitar sound.

I use Kyser’s Low-tension Quick Change capo, which I find works best for this setup, as its precisely engineered spring-loaded clamp squeezes the strings just firmly enough to produce a clean, buzz-free tone across all six strings without the highly annoying and frustrating pitch sharpening that can occur sometimes if I were to use a capo designed for an acoustic guitar.

With my SG’s slim-taper neck, thin, double-cutaway body and easy access to the upper frets, I’m able to place the capo as high as the 12th fret (!), which makes open chords and bluegrass-style licks sound very mandolin-like.

On a regular acoustic guitar, usually the highest you can place a capo is the 9th fret, due to that instrument’s typically massive neck heel, which gets in the way of the capo if you try to go any higher than that.

Being both a private guitar teacher and a longtime working musician, I’ve come up with many of my own original capo arrangements over the years that enable me (and my students) to favorably adapt keyboard-driven songs or ones with multiple guitar parts for consolidated performance on one guitar.

To do this, I use the finger-friendly “key of G” or “key of C” sets of chord voicings that are ever-popular among bluegrass, folk, country and rock/pop guitarists alike, and do so in a way that facilitates a consistently smooth, jangly, non-clunky accompaniment to a vocalist and the ability to additionally incorporate signature instrumental riffs into the chords in ways that are satisfyingly effective and easy on the hands.

Here are brief descriptions of five of the dozens of pop/rock song arrangements that I, the self-styled “capo crusader,” have crafted over the years, with basic chord shape illustrations.

Be sure to check out this feature’s accompanying video segments for a more detailed demonstration of how I play each song.

1. The Eagles – Desperado

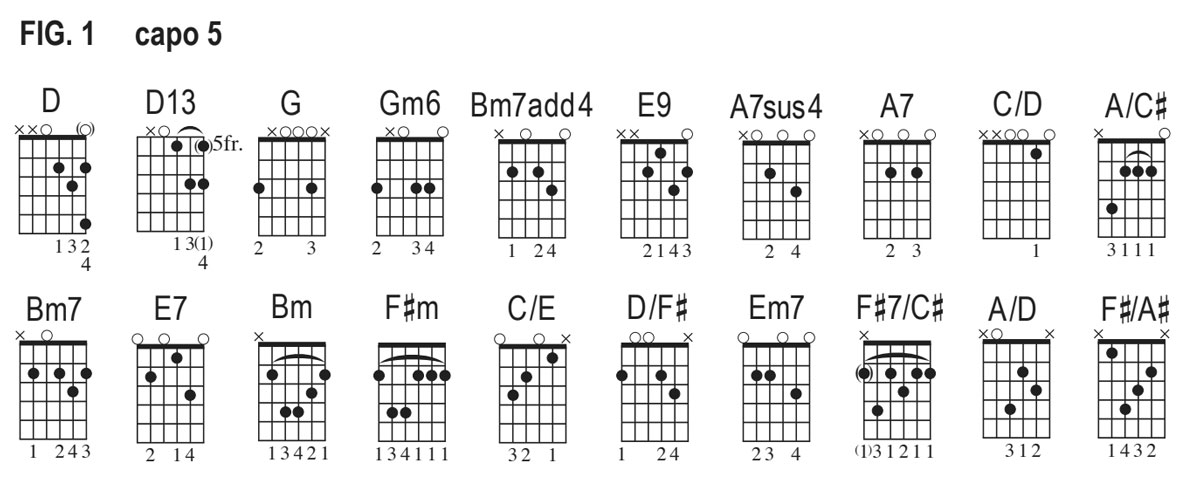

I devised an elegantly graceful way to adapt this song’s signature piano intro to guitar, by playing it as if it were in the key of D and capo-ing the strings at the 5th fret, which transposes everything up a perfect 4th to the song’s original key of G.

Figure 1 sketches out the basic chord shapes I play for the intro and the verses that follow, which, after the high D13 chord, are all played down in 1st position, relative to the capo, except for the 2nd-position Bm and F#m chords, which, as I mentioned earlier, are a little easier to fret than normal, thanks to the slightly lower action afforded by the capo.

As you’ll see in the video, I decided to make a couple of strategic alterations to the piano melody in the intro, to better accommodate the Bm7 chord voicing.

The capo also facilitates the performance of the song’s various country- and gospel-style chord and bass-line “walk-ups” and “walk-downs” that occur during the song’s third verse, with the chords C/E, D/F# and Em7 used as transition chords between D and G.

And since you’re playing mostly open chords here, this makes it fairly easy to comfortably sing and play the song without having to look down at your fretting hand, after you get past the intro.

The only chord shape that’s a little challenging to grab here is F#/A#, which is played between D/A and Bm7 at the end of the final verse, behind the lyrics “let somebody love you.” Rotate your wrist as needed to make the stretch.

2. The Who – Baba O'Riley

I'm especially proud of my arrangement of this iconic classic rock song, as it feels like this is how Who guitarist Pete Townshend might have originally composed it on acoustic guitar, perhaps in a parallel universe.

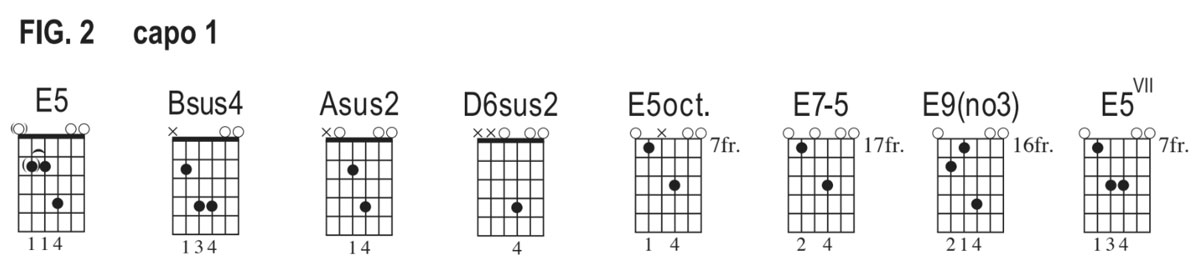

Performed capo 1, as if the song were in the key of E, I use the “drone-y” chord shapes illustrated in Figure 2, which are very similar to those employed by Dave Matthews in Crash Into Me, Dave Grohl in the Foo Fighters song Best of You and Incubus’ Mike Einziger in Pardon Me.

The concept is to use the open B and high E strings as ringing drones along with the fretted notes on the lower strings.

Due to the capo transposition here, everything sounds a half step higher, in Baba’s original key of F. To emulate the “noodly” sound of the keyboard part that begins the song on the original recording, which, by the way, was played by Townshend on a Lowrey organ using its automatic arpeggiator function, I play a recurring “root - 5th - octave - 5th” pattern and begin by gently “double picking” the fretted E and B notes on the D and G strings, along with the unison open B note and open high E string, letting the top four strings ring together.

The unison B notes are treated as one, like a course of unison strings on a 12-string guitar or mandolin, and together count as the middle note between the lower and higher E notes.

I do this four times then add the sustained melodic low bass notes that are introduced on the piano on the original recording, using an approach similar to what Matthews does on Crash Into Me, and then transition into a heavy strum at the end of the first verse, at the point where Keith Moon’s bombastic drums come crashing in on the record.

For the song’s faster, urgent-sound- ing instrumental outro vamp, I play a strummed-octaves melody based on the E Mixolydian mode (transposed up half step) up and down the A and G strings to recall some of the catchy, memorable licks and overall vibe and of the fiddle solo featured in the Who arrangement.

While doing this, I strum all six strings and let the open low E, B and high E ring out while muting the D string with the fleshy “paw” of my fret-hand index finger, as one would normally do when playing strummed octaves.

The result is a powerful, droning E5 power chord that richly shimmers behind the shifting strummed-octaves melody.

3. Aerosmith – Dream On

This is one of my favorite power ballads of all time, because of its beautifully sad and sophisticated chord changes, brilliantly composed on keyboard by singer Steven Tyler.

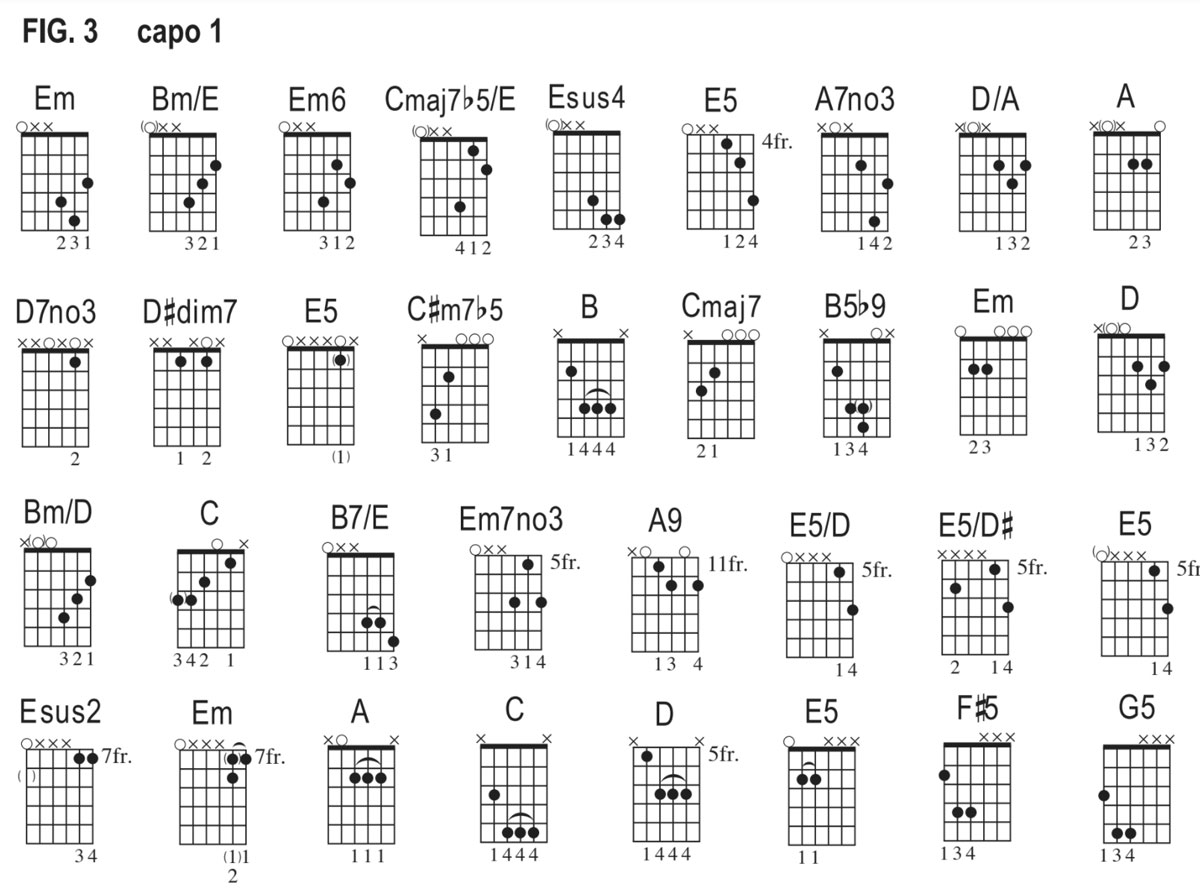

My arrangement uses essentially the same three-note chord shapes on the top three strings that guitarists Joe Perry and Brad Whitford play, except I use a capo at the 1st fret to perform the song as if it were in E minor and have everything automatically transposed up a half step to the original key of F minor.

The advantage to doing this is that I’m now able to pick the open low E, A and D strings at certain points, using hybrid picking, and let them ring with the fretted chords to emulate the sustained low F, Bb and Eb notes that bassist Tom Hamilton plays in Aerosmith’s arrangement and convey the complete harmonic picture in a way that sounds full and satisfying.

Figure 3 illustrates some of the shapes I use for the song’s intro, verses, pre-chorus and chorus sections. Particularly cool are 1) the rich open-string voicing for C#m7b5, 2) the B5b9 chord that has the b9 added with the shifting pinkie, and 3) the “minor-drop” instrumental-interlude voicings for Em, B7/E and Em7, which are flatpicked and arpeggiated with a sort of double-time 16th- note feel and followed by a pause on the lush, blissful A9 chord.

As you’ll see in the video, I play the lead licks pretty much the same way as Perry or Whitford, which are totally doable on electric guitar.

4. Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run

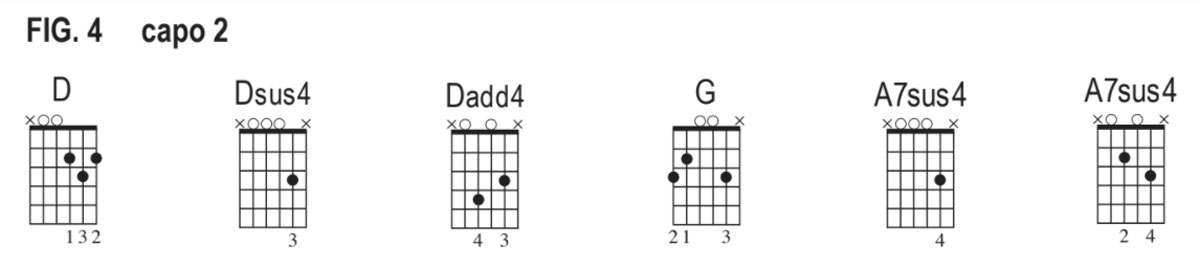

I play my one-guitar adaptation of this triumphant, powerful early anthem by the Boss with a capo at the 2nd fret, as if it were in the key of D, with the capo transposing everything up a whole step to match the original E Street Band arrangement’s key of E.

The concept here is to weave the intro’s signature single-note guitar melody, which Bruce recorded on his legendary early 50's Fender Esquire with a twangy, tremolo- effected tone, into the open chord voicings for D, G and A7sus4, in a way not unlike what John Lennon had cleverly done in the Beatles song Norwegian Wood.

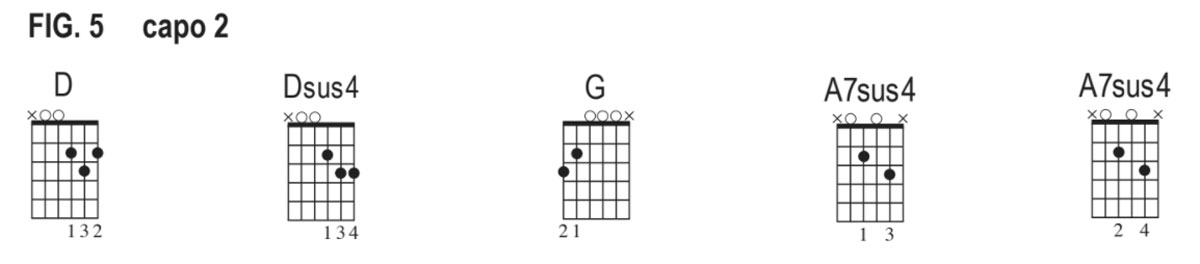

Spingsteen’s melody can be either played in its original “middle register,” on the A, D and G strings and worked into the middle of the aforementioned chords, additionally using the Dsus4 and Dadd4 voicings shown in Figure 4, or an octave higher, on the B and high E strings, using the shapes illustrated in Figure 5.

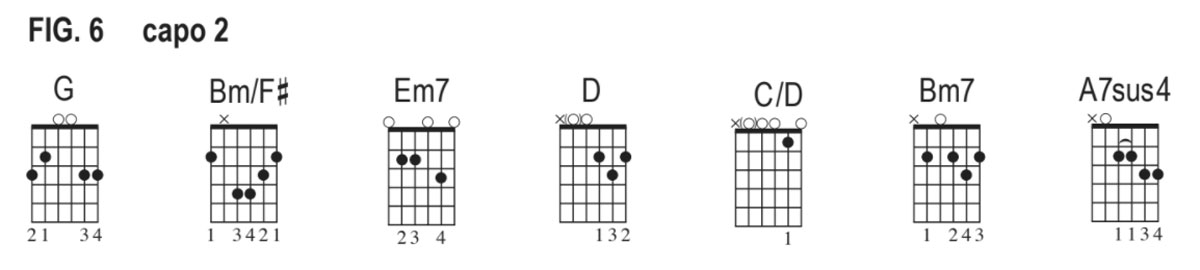

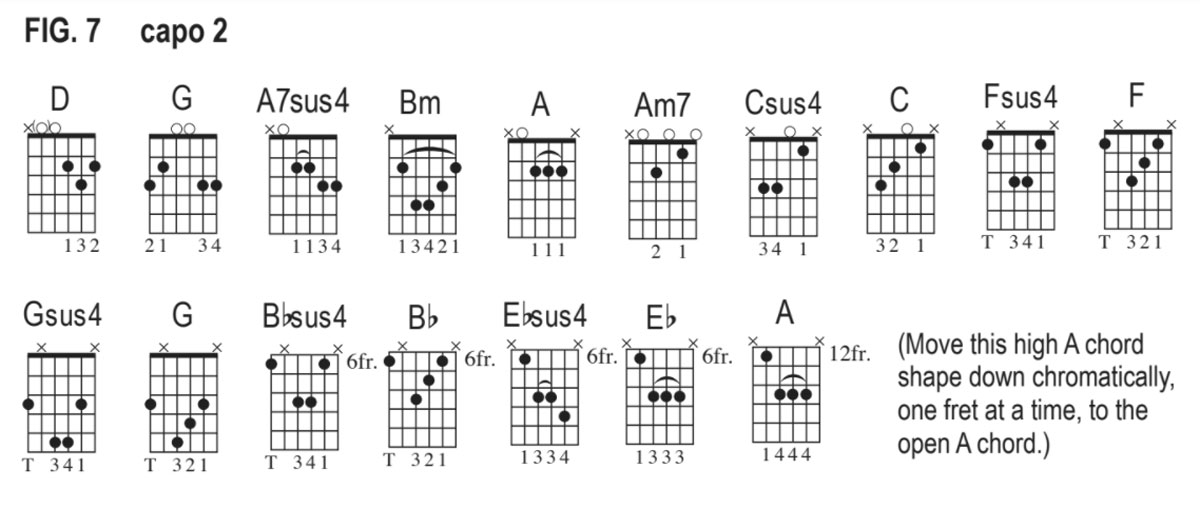

Figures 6 and 7 depict some of the chord shapes I use to play the song’s pre-chorus, chorus, sax solo and bridge sections. Notice the use of thumb fretting for some of the grips.

The harmonically ambitious instrumental interlude section that follows the bridge is all over the fretboard, with lots of chromatic movement, so be sure to check out the video demo for these additional parts.

5. Simon & Garfunkel – Bridge Over Troubled Water

Like Desperado, this classic, heart- warming, piano-driven pop ballad was another big challenge for me to adapt to a viable solo guitar accompaniment, and I’m rather proud of the approach and arrangement I took and came up with, which I feel does justice to pianist Larry Knechtel’s masterful and tastefully sophisticated, gospel-style harmonization of composer Paul Simon’s chords, which, by the way, were originally much simpler.

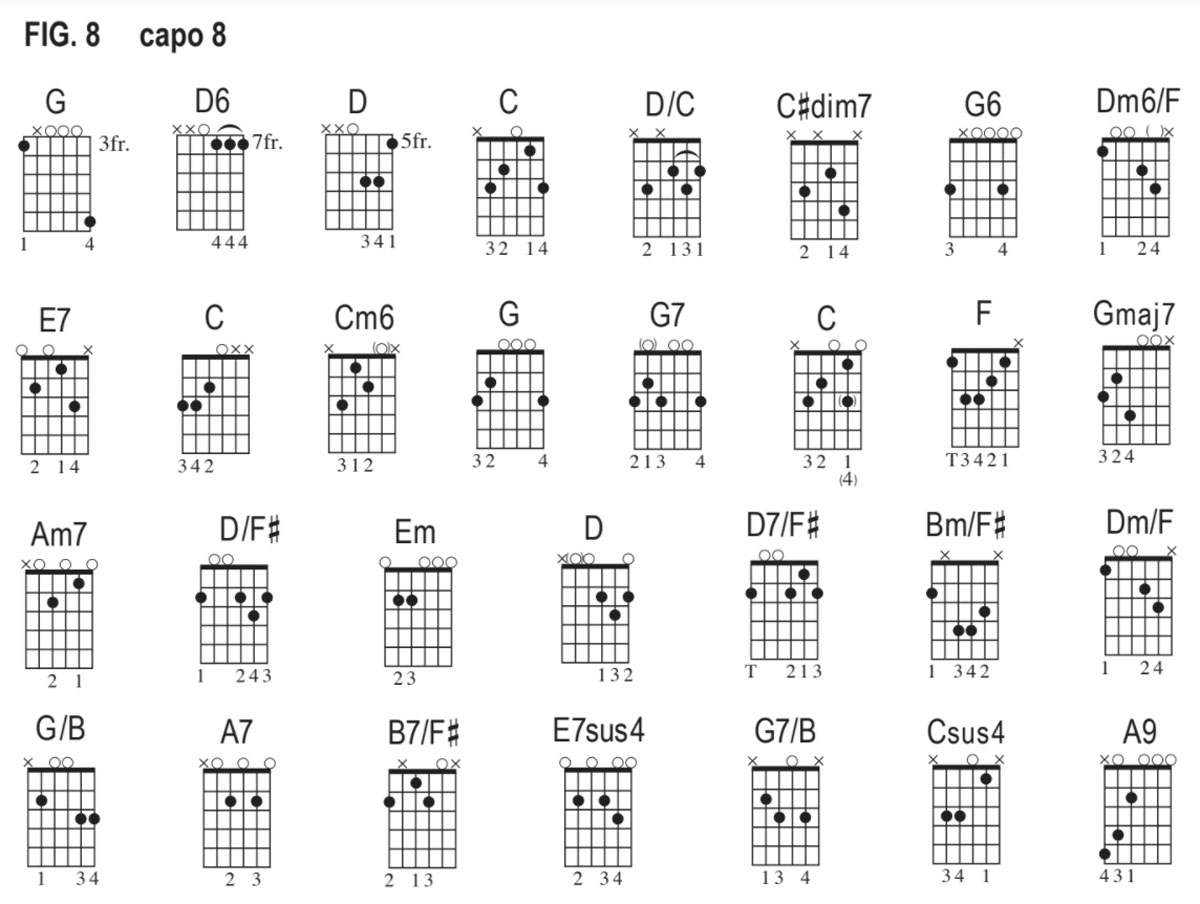

The song is in the concert key of Eb, so what I did was place my capo way up at the 8th fret and play the song as if it were in G, with the capo transposing everything up a minor 6th, to Eb.

Figure 8 sketches out most of the voicings I play to cop the melodic piano intro and the chord changes behind the verses and choruses. Notice how chime-y all the chords sound in this high register.

There’s some melodic activity applied to some of the chords during the intro and between the verses, so, again, be sure to check out the video to see how I do that.

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.