If you've ever tried to describe your guitar technique to other players, you've no doubt experienced the challenge of capturing its three-dimensional complexity in words.

Whether it's turning a doorknob or stirring coffee, guitarists frequently use a host of imprecise analogies to illustrate their hand movements.

These everyday images may seem helpful on the surface, but the problem is that they mean different things to different players. This can make learning and teaching even basic movements an exercise in frustration.

The good news is that a simple, common language for understanding guitar playing movements already exists.

And we players can take a big leap forward in our mechanical abilities just by learning it.

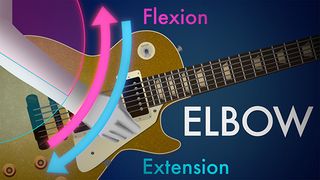

Elbow Flexion & Extension

Most guitar playing movements are, unsurprisingly, arm movements. And one of the most straightforward of these movements happens at the elbow joint, which pretty much only does two things: it flexes, and it extends.

If these movements look familiar to you, it’s because you see them all the time at the gym. The famous bicep curl is elbow flexion. And tricep extensions... well, now you know why they're called that! Of course, the arm itself might be in all sorts of different positions, but this is mostly thanks to the incredible 360-degree flexibility of the shoulder joint. But even with your arms over your head, the elbow joint itself is still just doing the same two movements, flexing and extending.

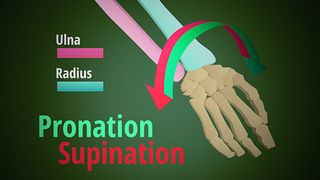

Forearm Rotation

Like elbow movement, the forearm really only does two things. It pronates and it supinates:

One way to remember which is which is that the term "supination" shares a latin root with the word “supplicate," which mean “to beg." And when you do that, you turn your palms upward. So supination is the act of rotating the forearm so that the palms turn upward. The reverse of this movement, turning the palms so that they face down, is pronation. Where things get more complicated is how this rotation actually works. There are two bones in the forearm, the ulna and the radius. And the reason it’s called the radius is because this is the bone that moves. It rotates around the ulna:

So when you rotate the forearm, most of the time, it’s actually only one bone that’s moving. This is pretty cool, because to look down and watch while you do this, you’d never guess that all this movement was actually coming from only half the forearm.

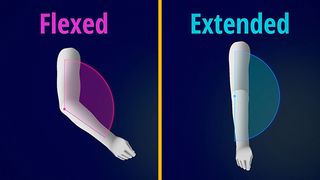

Orientations vs. Movements

But what about when you're describing a static arm or hand position, rather than a movement? Here's where we need to make a subtle change to our thinking. Supination and pronation both rotate the forearm across the same 180-degree range of motion, just in opposite directions. But if we pick one point along that arc and stop the arm at that point, then we need to know which half of that pie slice we're parked in:

If we say “supinated," as in the adjective, what we really mean is a fixed or static amount of supination, but only in the magenta pie slice, past the zero-degree centerline. Conversely, when we say “pronated," what we’re really referring to is a fixed amount of pronation any point in the turquoise pie slice, on the other side of the zero-degree line.

You'll notice that the palms aren't completely supinated or completely pronated in either scenario. That will rarely be the case in guitar playing. Even when we perform large strumming type movements, our forearms only tend to rotate within a much smaller range of movement, on either side of the neutral point. The same distinction applies to elbow movements, but with a twist. Flexion and extension each cover the entire range of movement. But any time when the elbow is bent, it’s flexed:

It’s only when the arm is completely straight that we’d call it extended. And that’s because the elbow doesn’t actually move past the point of full extension. Well, not unless you happen to be grappling with Ronda Rousey:

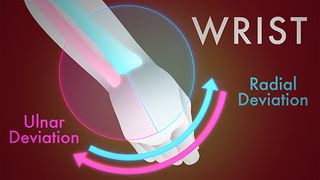

Wrist Deviation

Moving along down the arm, we raise the complexity ante a little further. That’s because the wrist can actually move in two different axes. This side-to-side, clock face-style movement, is called deviation:

In order to differentiate the two directions of the movement, we use the forearm bones we saw earlier. Movement toward the radius is called “radial deviation." And movement in the opposite direction, toward the ulna, is called “ulnar deviation." This is really just a fancy way of saying "back and forth", but notice how we're being very specific about which kind of back and forth.

This way, there can be no doubt about exactly how the hand is moving with respect to the rest of the arm. The back-and-forth movement of wrist deviation is extremely common in picking technique, and probably what most people mean when they use the generic term “picking from the wrist." This is the movement we see, for example, in the playing of the legendary Al DiMeola:

Flexion and Extension

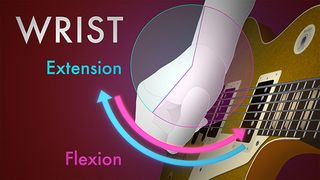

But this isn’t the only trick up your sleeve, because the wrist is actually capable of a whole other dimension of movement:

This is wrist flexion and extension. It's the same movement you make when knocking on a door. Flexion is the actual knock, and extension is pulling the hand back to the starting position. Even though this is not a movement most us associate with picking technique, it's extremely common. Some players, like Steve Morse and Marty Friedman, base the bulk of their alternate picking movement on flexion and extension. And others use flexion and extension as critical ingredients alongside other movements like deviation and rotation.

Wrist Orientations

And just as with elbow and forearm movement, we can imagine fixed versions of all these wrist orientations to describe different static hand and arm positions. For example, this would be an ulnar deviated wrist:

And this would be a flexed wrist:

And this would be a combination of both:

The Three Axes

In fact, notice that all three of the wrist and forearm movements operate in planes which are at right angles to one other:

This amazing fact is not a coincidence, but a key to the incredible versatility of the human hand. Simply by combining these three fundamental movements, we can generate any three-dimensional hand movement you’ll ever use in guitar playing. And that’s why this kind of thinking is so powerful. If breakfast is the foundation of your day, then understanding these basic movements can be the foundation of your mechanical knowledge.

You’ll not only be able to speak to other players in a language that everyone will understand, but you’ll also become much more aware of the movements you’re already making.

For more on essential guitar anatomy and mechanics, check out Cracking the Code.

Troy Grady is the creator of Cracking the Code, a documentary series with a unique analytical approach to understanding guitar technique. Melding archival footage, in-depth interviews, painstakingly crafted animation and custom soundtrack, it’s a pop-science investigation of an age-old mystery: Why are some players seemingly super-powered?