“The Grateful Dead wouldn’t let us use their amps. Ray was aghast – he kept saying, ‘Pigpen? Someone named Pigpen won’t let me use his instrument?’” With a volatile lead singer and no bass player, they left an indelible mark on rock

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

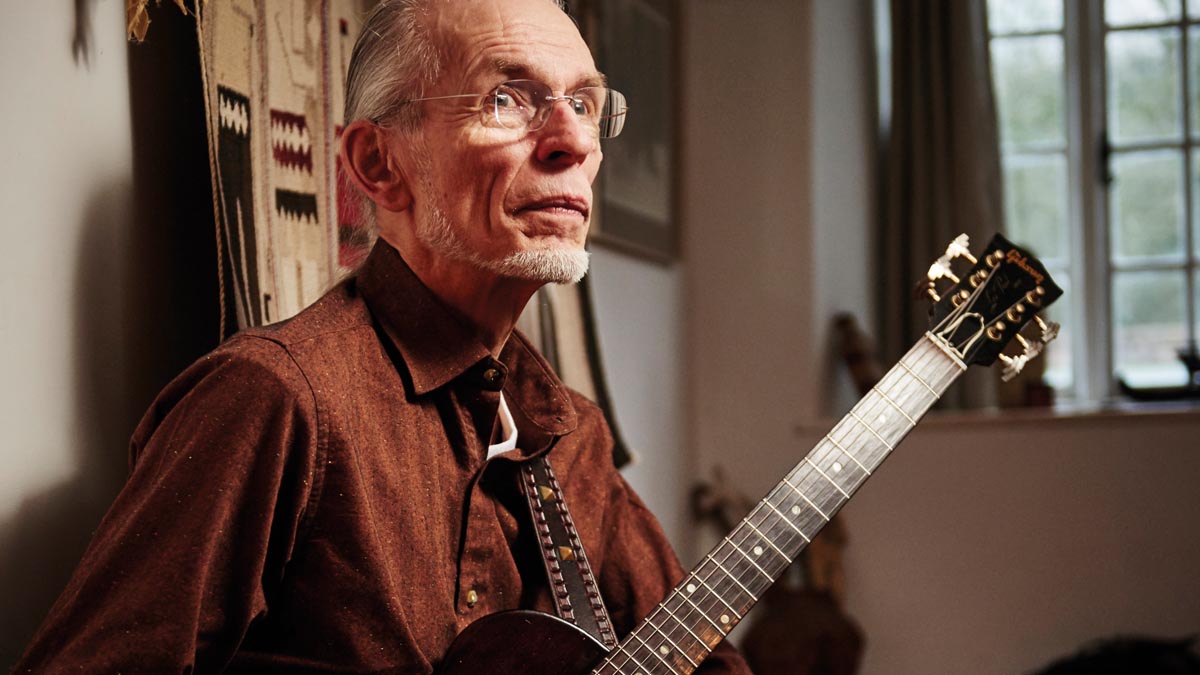

“It was hard living with Jim.”

Robby Krieger is talking about his days as guitarist with the Doors, reflecting on his role as creative sidekick to one of rock’s all-time great lyricists, singers, sex symbols, and extreme personalities, Jim Morrison.

“It would have been so great if we’d just had a guy like Sting,” says Krieger wistfully. “You know, a normal guy who’s extremely talented, too. Someone who didn’t have to be on the verge of life and death every second of his life.”

The guitarist laughs at his own fantasy. He knows better than anyone that it was Morrison’s inner demons, which surfaced all too frequently, that gave the Doors’ music its resonance and power. But while Morrison was undoubtedly one of rock’s great visionaries, the contributions of the other Doors to the band’s unique sound and success cannot be overlooked.

The blues-based, often hypnotic music created by Krieger, organist Ray Manzarek, and drummer John Densmore perfectly complemented Morrison’s commanding, sensual vocals and mesmerizing lyrics. And it was actually Krieger who penned many of the Doors’ greatest songs and biggest hits, including Light My Fire, Love Me Two Times, and Touch Me.

Remarkably, when Krieger joined the Doors in 1965 he was only 18 years old and had been playing guitar for just two years – electric guitar a mere six months.

“I really learned to play as a member of the Doors,” he asserts. “I just tried to sound like myself – I consciously avoided copying Chuck Berry or B.B. King, because that’s what everyone was doing. I tried to come up with the right part for the song and play something that would complement Jim’s singing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It must have worked,” he adds coyly. “I think we came up with a pretty good body of work.”

Pretty good, yes. Good enough to have gotten the Doors inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame last January and to have inspired Oliver Stone’s reverential 1991 biopic. And, most of all, good enough to enthrall three decades of rock fans with music that remains as powerful and profound in the Nineties as it was in the Sixties.

Robby Krieger cannot escape his past with the Doors, even though the band essentially died with Morrison in 1971. Although he has remained active, touring regularly and recording seven solo albums dominated by instrumental music, Krieger says, “I realized pretty quickly that I would never again have another band like the Doors.

“Music has become more of a fun thing for me, much like painting is – something that’s personally rewarding. It’s what I do and how I identify myself: ‘I’m Robby Krieger, guitarist.’”

Most people would say: ‘Robby Krieger, Doors guitarist.’

What follows are Krieger’s recollections of the Doors’ career, from their 1967 self-titled debut to 1971’s brilliant swan song, L.A. Woman.

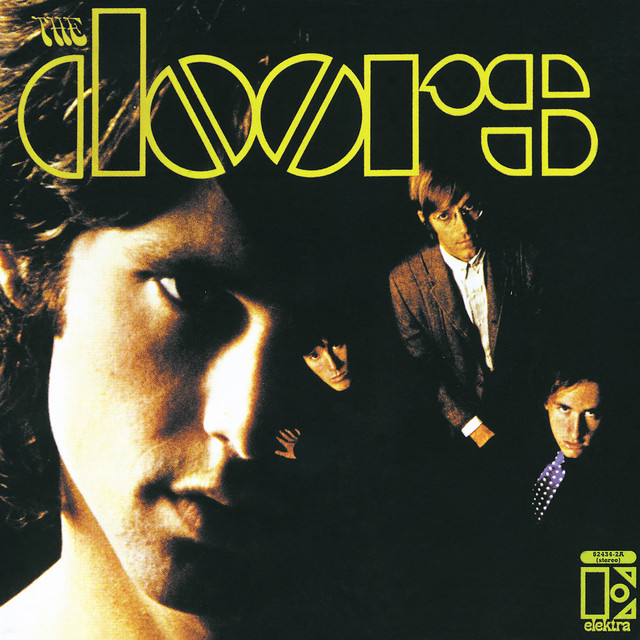

The Doors (January 1967)

What was your first impression of Jim Morrison?

“I first met him when he came to my house with John Densmore and he seemed pretty normal. I didn’t really get a sense that there was anything unusual about him until the end of our first rehearsal. Initially, everything was cool. Then this guy came looking for Jim. Something had gone wrong with a dope deal, and Jim just went nuts. Absolutely bananas. I thought, ‘Jesus Christ, this guy’s not normal.’”

What were your impressions of Ray Manzarek?

“When I first met him, he was the ‘big man on campus’ at the UCLA film school. In fact, our first gig as a band was to provide music for one of his student films. Afterwards, Ray got up in front of an auditorium full of people and gave a speech. I remember it well, because he had them in the palm of his hand. He was downright mesmerizing.

We had this group which we all knew had the potential to be something really big, and Jim was trying to sabotage it by fucking up at every turn

“He was a major character, but Jim kind of kept him in his place. Jim was so out there that Ray’s personality was overwhelmed – which, oddly enough, created a good balance.”

And you were pretty much what you appeared to be: a nice, quiet guy who fit in between these two powerful personalities?

“Well, dealing with Jim kind of changed me, too, because I was pretty crazy myself. I was the first one at my school to try acid and I was always the one pushing things. Then I got into the Doors and I couldn’t hold a candle to Jim and Ray. [laughs] But I had already gone through acid and I was onto meditation by the time I joined the Doors – I actually met John at meditation class – so I had already mellowed out.”

When were the Doors thrown out of the Whisky-A-Go-Go for performing The End?

“Well, that’s overstating it a little bit. That whole incident has been blown out of proportion. There was a fight with the owner and we were thrown out, but I don’t think we were actually fired. We kept playing the Whisky after that.”

Jim’s antics are held in such reverence now. Were they funny at the time?

“It was always a bummer. We had this group which we all knew had the potential to be something really big, and Jim was trying to sabotage it by fucking up at every turn. We would call a rehearsal, Jim wouldn’t show, and we’d get a call from Blythe, Arizona, telling us that he was in jail.”

Yet you guys were amazingly productive. You produced six studio albums in three or four years. Were his work habits really that bad?

“No, the music was all he lived for. A lot of times he was at the office when we weren’t. He’d even live there sometimes, because that was his whole life. We all had lives other than the Doors, but he didn’t, and he kind of resented that. He felt like he was living it 24 hours a day, and we weren’t. And he was right.

“But the recording sessions really bored him. We had to hang around interminably until they got the drum sound down and all that shit, so I can’t blame him for going crazy. Paul Rothchild, our producer, was a real perfectionist.”

How important was Paul to your music?

“It really differed from album to album. On the first one, he just turned on the mic and stepped out of the way. The second album, when we actually had a budget, Paul really got involved in the sound.

“We were all kind of freaked out recording the first album because we didn’t know what it would be like. For example, it really bothered us that we couldn’t turn up as loud as we wanted.”

Yet it really sounds like you were all playing with total abandon.

“That’s because we had been playing those songs for so long that we really had the material down cold. Everything was cut in one or two takes.”

Your version of Back Door Man is really effective. Were there any debates about how faithful you should be to the original version?

“No. For one thing, we probably weren’t good enough musicians to do exact copies and we knew that Jim would never sing it anywhere near the original anyhow. So we just went on our own.”

For years it was a little-known fact that you wrote Light My Fire. That changed when Oliver Stone made it a point to show how the song evolved in his movie, The Doors. Was it as simple as pulling a crumpled piece of paper out of your pocket and offering it to the band like the movie suggests?

“It’s pretty close. Jim had been writing all the songs and then one day we realized we didn’t have enough tunes, so he said, ‘Hey, why don’t you guys try and write songs?’ I wrote Light My Fire that night and brought it to the next rehearsal. It was my idea to have that scene in the movie, by the way. I wanted it there because it’s always kind of bugged me that so many people don’t know I was the composer.”

I always felt like three players simultaneously

Your solo on Light My Fire is truly one of your shining moments as a guitarist. Was it improvised in the studio?

“It was the kind of solo that I usually did, but it was different every night. To be honest, the one on the record is not one of my better versions. I only had two tries at it. But it’s not bad; I’m glad it was as good as it was.”

Was the whole album recorded live?

“No. Jim always sang with us, but they rarely used the scratch vocal. The End was an exception.”

What do you think of the song now?

“I think that particular version of The End was nowhere near as good as the way we played it many other times.

“All the songs on the first album were like skeletons of how we really played them. It was just a combination of not having any studio experience and having to do everything so fast. I also think that studios are, by nature, limiting. You cannot get the sound of five big amplifiers on a little piece of tape.”

Did you ever think about how strange it was not to have a bass player?

“Definitely. We always thought about that. We wanted a bass player, and we auditioned a few – but we never could find one who was right. Looking back, I’m glad we didn’t, because the Doors’ sound was largely a result of the fact that Ray had to play really simple bass lines, which gave the music a hypnotic feel.

“And not having a bass player affected my guitar playing a lot. It made me play more bass notes to fill out the bottom. Not having a rhythm player also made me play differently to fill out the sound. And then, of course, I played lead, so I always felt like three players simultaneously.”

Light My Fire, the first song you ever wrote, was a number-one hit. It’s sudden success must have been mind-boggling.

“It wasn’t that sudden. It actually felt like forever to us. We started the band in 1965, and nothing happened for two years. We were going crazy. Finally, after being turned down by everyone in town, Elektra signed us. Our first single bombed, and it was another six months before Light My Fire hit. So it seemed like a long time. We felt like veterans.”

Did you use your standard gear in the studio? Were you playing an SG?

“Yeah, though the first red one I had was a Melody Maker. I had a few red SGs in the Doors, but they’re all gone now, mostly stolen or lost. Amp-wise, I usually used a Twin Reverb in the studio.”

You almost allowed Light My Fire to be used in a car commercial before Jim put an end to it. Did Jim do the right thing?

“Oh yeah, absolutely. In fact, it’s been our policy to reject any subsequent offers – and we’ve had quite a few. I really hate it when I see other bands selling their music to commercials. And by the time a big corporation is interested in using your music, you don’t need the money. So there’s really no excuse.”

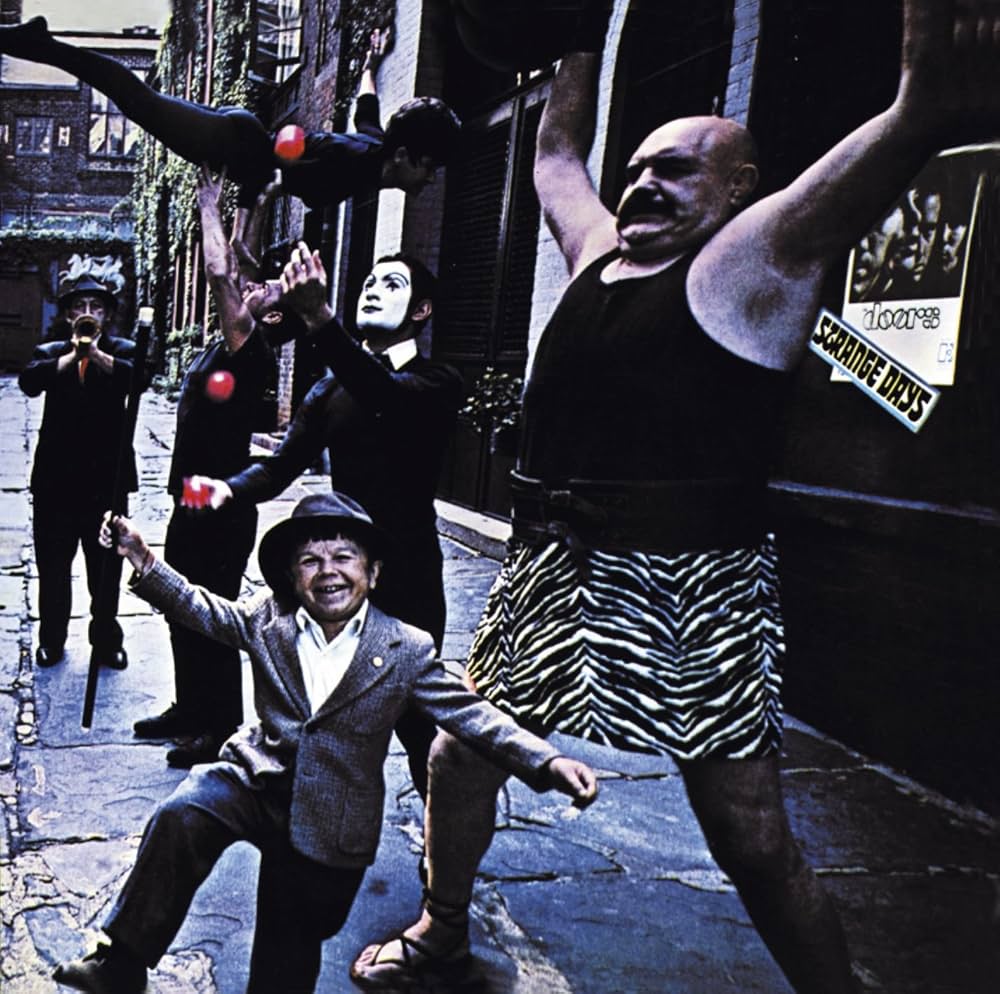

Strange Days (September 1967)

When the second album came out it was attacked by many critics as being a retread of the first. Do you think that was valid criticism?

“Only on one count. I’ll admit that When the Music’s Over was similar to The End in length and structure, but so what? Something works, so you do it again. It’s one of my favorite songs.”

I don’t think that Morrison’s poetry rap is quite as interesting on When the Music’s Over as The End.

“No, it’s not. How can you possibly top The End? What’s left once you’ve fucked your mother and killed your father? [laughs] The reason it’s my favorite song is my solo – I think it’s my best.”

That solo is composed of two solos being played simultaneously. Did you improvise both of them on the spot?

“Pretty much. In fact, I’ve never been able to reproduce them. That solo was really a challenge because the harmony is static. I had to play 56 bars over the same riff, which isn’t easy. It’s a lot easier to play something over an interesting chord progression. But we did that a lot because we were really into [saxophonist] John Coltrane, who pioneered ‘modal’ jazz and soloed brilliantly over static harmonies and minimal chord progressions.

“I was always trying to play something that sounded like him – just totally out there in terms of tonality. I think When the Music’s Over is the closest I ever came.”

You recorded Strange Days less than a year after your debut. Did Elektra put a lot of pressure on you?

“No, we were ready. We had tons of material for the first two albums; the pressure came on the third album. We ran out of stuff and Jim was pretty fucked up on liquor by then, so it was hard to write with him, and that’s when I started writing more of my own songs. It was also difficult to write while we were touring, so we started writing a lot more in the studio.”

What was life on the road with the Doors like?

“Not as crazy as you would think. At first, it was mostly teenyboppers and groupies and a few local nuts hanging around. But a couple of years down the road, when people realized how weird we were, we really started drawing some creeps. We still do, I might add – Morrison wannabes show up on my doorstep all the time. And they always want to sing. [laughs]”

Speaking of weirdoes, People Are Strange has a great chord progression. Did you write that?

“Yeah. Jim came up to my house in Laurel Canyon one night, and he was in one of his suicidal, downer moods. So John said, ‘Come on, Jim, we’ll go see the sunset. That’ll get you out of this.’

“We went up to the top of Laurel Canyon and it was incredibly beautiful – we were looking down on the sun reflecting off the top of the clouds. Jim had a total mood flip-flop, and said, ‘Wow! Now I know why I felt like that. It’s because if you’re strange, people are strange.’ And he wrote the lyrics right there. Then I came up with the music and we went back down the hill.”

Why wasn’t Moonlight Drive, the first song you wrote and rehearsed together, on the first album?

“It wasn’t really the first song: Indian Summer was, and Moonlight Drive was the second. But we didn’t think the version that we cut was good enough, so we decided to drop it off the first album and try again next time.

“Unfortunately, we’ve never been able to find the damn master for the first version. I think we may have found it now, and I hope I’m right, because I always thought it was good. It was totally different than the one on Strange Days. It was real dark and laid-back, very spooky.”

Any strange memories from the Strange Days album?

“One time, we were getting ready to leave for the night and Jim didn’t want to stop because he was feeling good. He kept saying, ‘Man, I want to play all night.’ But we were all tired and wanted to go home.

There were all these instruments in the studio from an orchestra session – harpsichords and pianos and timpani. We all started banging on them and fumbling around inside the pianos, and there were 10 or 12 people just screaming at the top of their lungs

“Jim finally left, but he came back half an hour later, climbed over the fence, broke into the studio, took out the fire extinguisher, and sprayed it into the piano and all over everything. It was quite a surprise in the morning. [laughs]”

Were you guys around when Jim recorded Horse Latitudes?

“Yeah. He said he had a poem he wanted to read and he wanted something real weird to back it. There were all these instruments in the studio from an orchestra session – harpsichords and pianos and timpani. We all started banging on them and fumbling around inside the pianos, and there were 10 or 12 people just screaming at the top of their lungs. After we laid that down, Jim overdubbed the poem.

“The funny thing was, as we were listening back at full volume and Jim was reading, the guys from the Jefferson Airplane came straggling in – high as kites, or course. They stared at us like we were out of our minds, but we just acted casual and said, ‘Oh yeah, this is one of our songs.’ [laughs]”

Were you friends with them?

“Sort of. We always played on the same bill, but we didn’t really hang out much. There was always a bit of competitive vibe – to see who could blow who off the stage.

“We didn’t hang out with other musicians that much – just Van Morrison when he came to town, and occasionally the guys in Buffalo Springfield.

“We didn’t get too close with the San Francisco groups – especially the Grateful Dead, who wouldn’t let us use their amps one night. We had a gig at Beverly Hills High School in the afternoon and then one about an hour up the coast in Santa Barbara, so we left our gear, figuring the Dead would let us use their stuff. You’d always let people use your amps in those days, but they just refused. I ended up playing through a Pignose or something equally ridiculous.

“Ray was aghast at the fact that Pigpen wouldn’t let him use his organ. He kept saying, ‘Pigpen? Someone named Pigpen won’t let me use his instrument? I could catch cooties from his organ.’ He couldn’t believe it.”

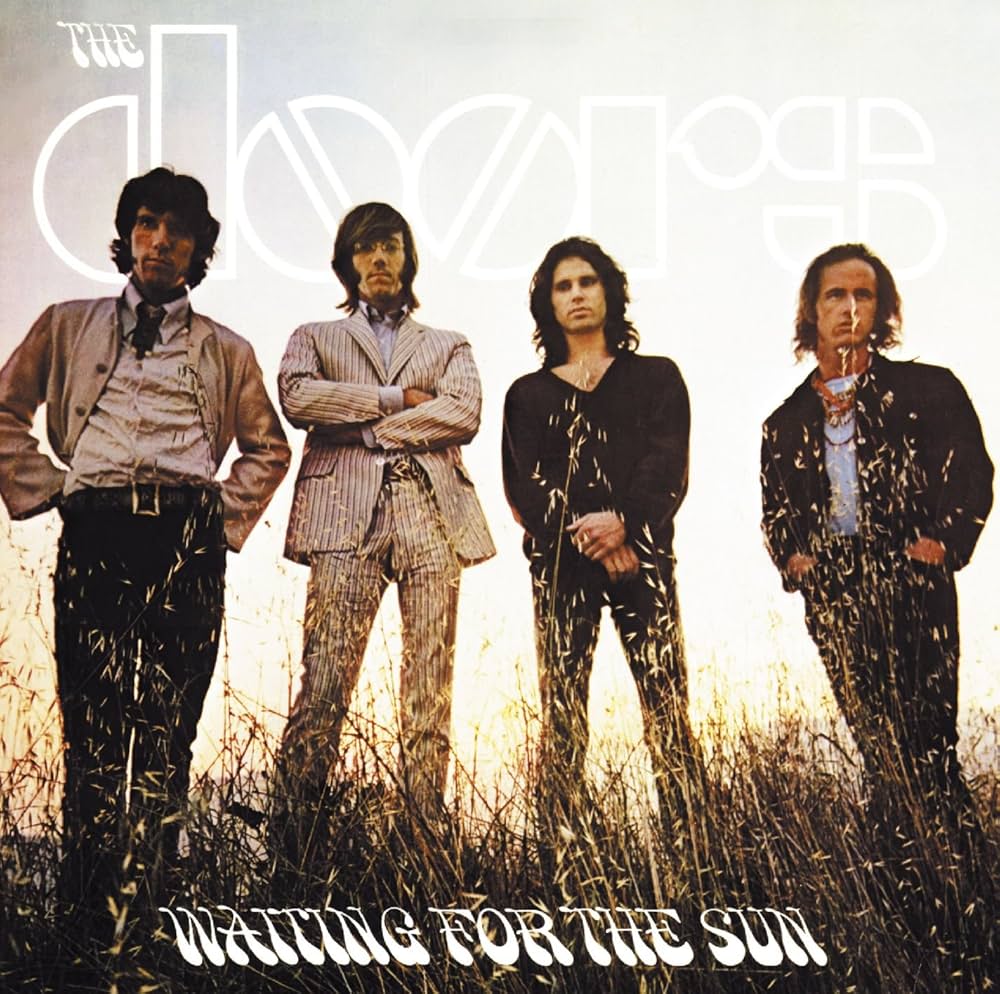

Waiting For The Sun (July 1968)

It seems like the band were in a creative lull and feeling a lot of pressure by the third album. Do you see a band like Pearl Jam going through a similar thing?

“Their situation is a lot different, but, yes, I see the similarities. I know Eddie [Vedder] – he sang with us at our induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame last year [1993] – and he wants to be like Jim. He was drilling me about Jim – asking me a million questions about how Jim would have reacted to various situations. And he is kind of a troubled person and a very serious guy, like Jim was. But I don’t think he, or anyone else in that band, is too fucked up to write good material.

“They may not be the straightest people in the world, but it’s not like our situation, where you have a guy who’s really out of control. Eddie’s not like that; he knows what he’s doing.”

Does it trouble you to see someone emulate a person whose self-destruction you witnessed?

“Yeah, it really does. I always tell people, ‘Don’t drink because Jim drank. That was a mistake. That’s what fucked him up.’ If it weren’t for the booze he might still be writing today.”

Had his drinking gotten seriously worse when you were recording Waiting for the Sun?

“Definitely. That’s when the liquor really started being a problem. Before that, everything was more or less fine. LSD was no problem because it was a creative thing. There’s nothing good about liquor – it just fucks you up – though at first it relaxes you, which is what you probably need after taking eight-zillion acid trips. [laughs]”

Hello, I Love You was a number-one hit and Waiting for the Sun topped the album charts. Can that kind of success get you through a creative lull?

“It helped a lot. In fact, we were just going out on tour when Hello, I Love You hit number one, and it really buoyed our spirits. People always think that we stole that track from the Kinks’ All Day and All of the Night, but we weren’t thinking of them at all. What I did steal was the drumbeat: I told John to play something like Sunshine of Your Love. So, we ripped off the Cream, not the Kinks.”

What specific recollections do you have of these sessions?

“A lot of very horrible ones. By that time, Jim was being taken advantage of by various hangers-on. He would bring them to the studio and Rothchild would go crazy – all these drunken assholes would be hanging around, fucking in the echo chamber and pissing in the closets. It was a mess.

“Jim would drink with anybody because we wouldn’t drink with him. He would take on all these assholes, who used him: ‘Hey, we’re hanging with Jumbo.’ And they wouldn’t care how fucked up he got – they’d leave him on somebody’s doorstep in his own puke.”

At what point did you guys refuse to drink with him?

“I never drank with him because I didn’t like to drink to excess and he loved to go until he couldn’t see. I knew what was coming and hated to see it, so I would usually be gone by that point. John and Ray felt the same way.”

Were you three using a lot of drugs at that point?

“No. Not at all. And the fact that Jim was using so much made us use even less. The romance was definitely gone. Once in a while he would talk me into taking acid – just like you saw in the movie – but not often.”

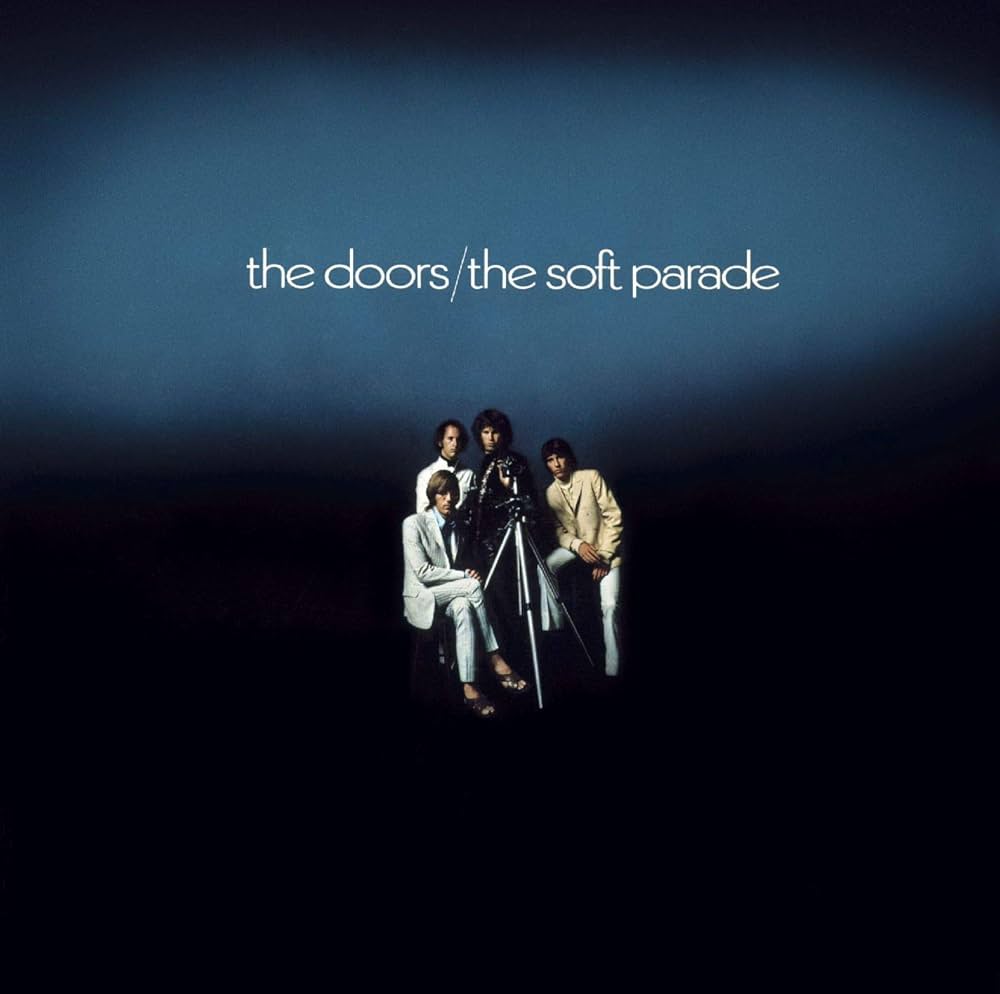

The Soft Parade (July 1969)

The Soft Parade features several heavily orchestrated, intricately arranged songs. Were you compelled to go into this direction because of the Beatles?

“Yeah, totally. In those days you had to try to keep up with the Beatles! But, to be honest, I didn’t really like orchestrating the songs. It definitely wasn’t my idea – it was Paul Rothchild’s. I never would have done it.”

Does it sound better to you now?

“Actually, it does sound better with time. But I never thought it sounded bad – I just thought it didn’t sound like us. The Doors were lost. It was Jim and the orchestra.”

This was the first album where you had individual songwriting credits.

“Right. Jim originally wanted everything to say ‘written by the Doors,’ to keep things mysterious. But everybody just took it for granted that he wrote everything. I think he realized that wasn’t fair and wanted to give others credit.”

Did he actually write the music on those songs where he alone is credited?

“No. He would hear the song in his head. But he didn’t play anything, so he would sing a vocal melody, and we would have to figure out what to do. But a lot of times he just had a poem on paper and I would come up with something. Other times I would come up with a melody, and he’d put words to it.”

What about the Soft Parade sessions sticks out in your mind?

“The endless mixing sessions. That was a very long, drawn-out album. We spent more money on it than we did on any other album. And Jim was hard to find. All the mixing bored the hell out of him. But I think his drinking problem wasn’t as bad as it was on Waiting for the Sun, because he had started making a film, which kept him busy.

“There was one funny thing that happened. This crazy guy appeared and apparently he thought that The Celebration of the Lizard [a Morrison poem which appeared on Waiting for the Sun] was written about him. He was yelling, ‘How did you know that I’m the Lizard King, goddamn it! That’s me. You wrote a song about me!’ And he smacked Ray right in the eye because he thought Ray was Jim. Ray had his glasses on and they just crumpled. It was a mess.”

Before the poem appeared had you ever heard Jim refer to himself as the Lizard King?

“He was always obsessed with lizards – he loved that kind of stuff because he’d seen it on acid a lot. But I don’t know when he came up with ‘I am the Lizard King.’ I think he wished he had never said that. It was just another thing he had to live up to.”

During the Soft Parade tour, your Miami concert erupted in pandemonium and was canceled. Later, Jim was charged with indecent exposure. What do you remember of the concert?

“Well, first of all, Jim did not pull it out. But it was bedlam, just total craziness. The place was oversold, thousands of people swarmed the stage, and it collapsed. I remember Jim just rolling around in the midst of all those people and I was wondering if we would ever get out of there. It was very much like in the movie – they did a real good job on that one.”

We really did have the sense that we had pushed the system to the edge, and finally they were pushing back

But you had no sense that the incident was going to turn into such a big thing?

“No, hell no! Okay, the concert was fucked up, and we didn’t finish, but nobody was angry, nobody asked for their money back. And the cops were friendly – they sat around drinking beers with us after the show. Nothing happened until a week later, when somebody decided to make a stink about it.

“Some politician decided to make their career at our expense. Then it fucked everything up. We couldn’t play anywhere for a year. The Hall Managers’ Association basically banned us.”

Did Jim feel very persecuted?

“I’m sure he did. But he wasn’t surprised. He knew he was pushing authority as far as it could go. We really did have the sense that we had pushed the system to the edge, and finally they were pushing back.”

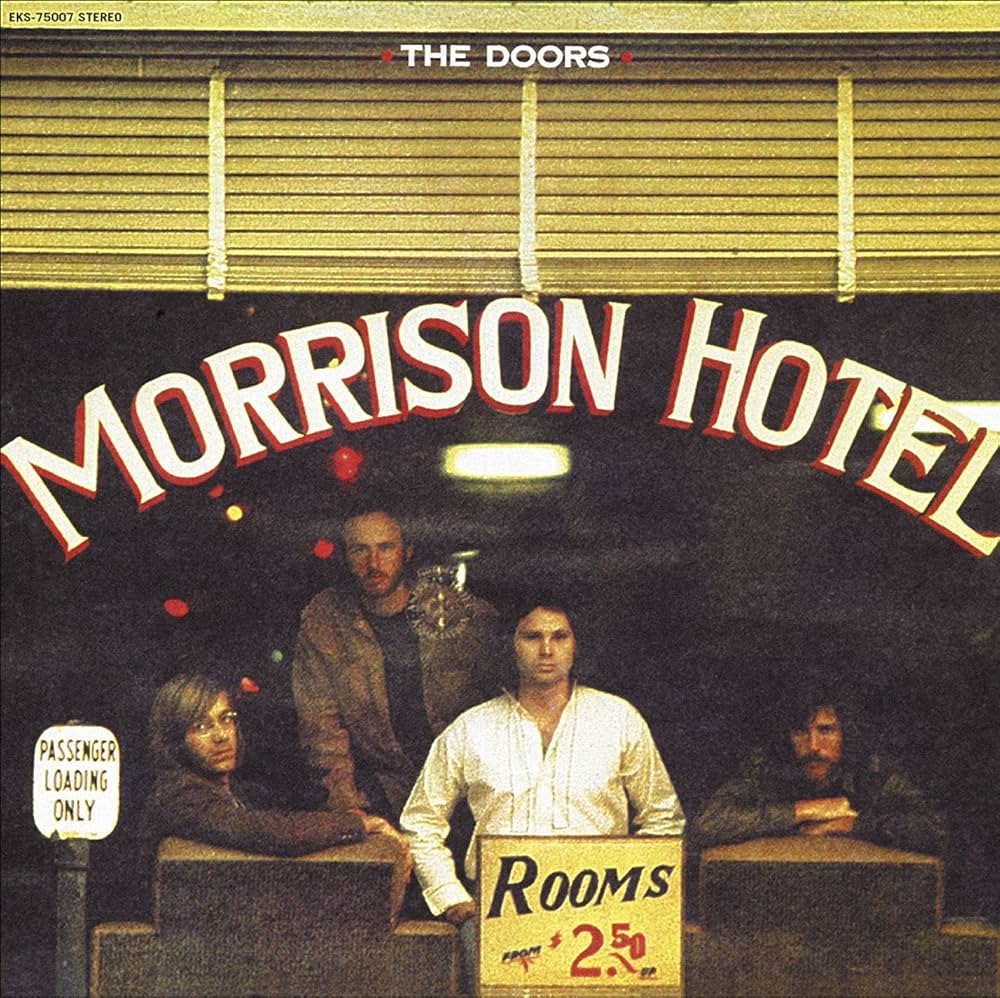

Morrison Hotel (February 1970)

Roadhouse Blues and a couple of other songs on Morrison Hotel hinted at the changes to come on L.A. Woman – heading in a bluesier, more bare-bones direction.

“I think it was a reaction to the overproduction of The Soft Parade. We wanted to get back to basics. Roadhouse Blues is one of my personal favorites. I was always proud of that song because, as simple as it is, it’s not just another blues. That one little lick makes it a song, and I think that sums up the genius of the Doors.

“I think that song stands up really well as an example of what made us a great band. And the session was really cool – one of my fondest memories of the band. We cut the tune live, with John Sebastian playing harp and Lonnie Mack playing bass – he came up with that fantastic bass line.”

How did Mack end up on there?

“He just happened to be hanging around. I think he had a contract with Elektra and wasn’t recording so they gave him a job at the studio. We just said, ‘Hey, why don’t you play bass?’”

You co-wrote Peace Frog with Jim.

“Yes. I had written the music, we rehearsed it up, and it was really happening, but we didn’t have any lyrics and Jim wasn’t around. We just said, ‘Fuck it, let’s record it. He’ll come up with something.’ And he did. He took out his poetry book and found a poem that fit. But it always seemed kind of forced to me, to tell you the truth.”

The legend has Ray and Jim being very tight, but you’re the one who wrote with him a lot.

“In the very early days Ray was very close with Jim; Jim actually lived with Ray and his wife. He was almost like their son, and he was great for a while – he wasn’t drinking or anything. The problem was that Ray became a father figure, so Jim rebelled.

“He fucked their house up – trashed it on more than one occasion – and took advantage of them in many ways. Then I joined the band and sort of latched on to Jim, and we hung out a lot.

“Ray worked up all the early songs with Jim – everything on the first album. Then I wrote a lot with Jim – before I started really writing on my own – and those songs went mostly on the second and third albums.”

Did you ever talk about lyrics with Jim?

“Not much. He didn’t like to explain lyrics because he wanted people to interpret them themselves. But he thought about that stuff a lot. He was also somewhat into pure impressionism – which I think is what he liked about my songs. I always tried to write something that just fit the music, even if it didn’t especially mean anything.”

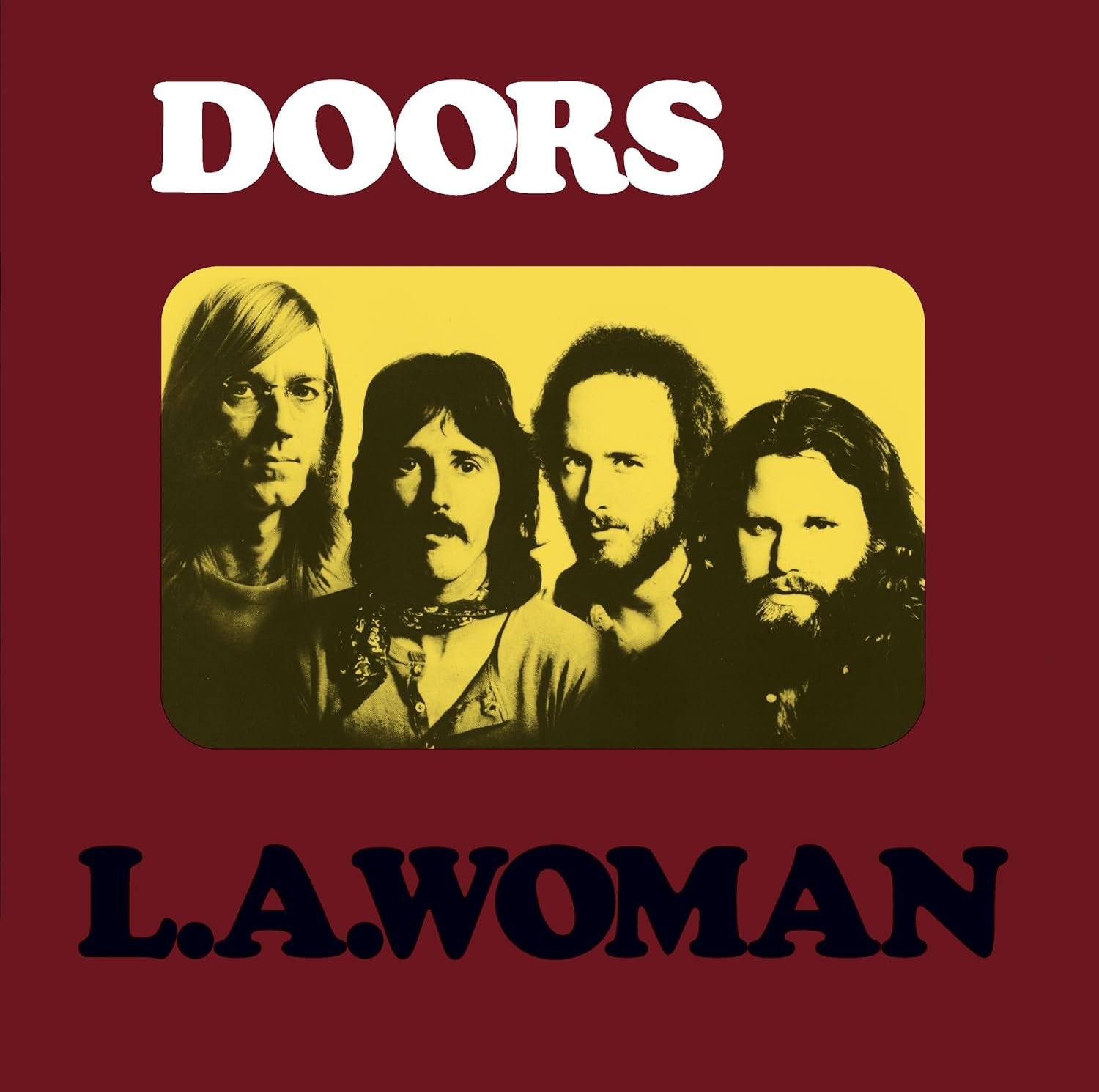

L.A. Woman (April 1971)

Legend has it that L.A. Woman was cut entirely live.

“Not entirely, but a lot of it was live, and the song L.A. Woman was completely live. I think that could be the quintessential Doors song, and the way we came up with it was amazing.

“We just started playing and it came together as if by magic. Jim made a lot of it up as he went along, which is amazing because I think it’s one of his most poetic songs. I can remember Jim sitting in the bathroom with the mic singing and all of us just having a great time.”

That album was the first time you had a rhythm guitarist – Marc Benno.

“That was basically just so we could do it live. It freed me up. And we thought it might add a different flavor. I actually enjoyed it, and I didn’t have to do as much overdubbing.”

You still did some overdubbing; it sounds like there are at least four guitar tracks on I’ve Been Down So Long.

“Yeah, there probably are. Ray played a guitar and Benno played, and I probably overdubbed one, too. I think I also overdubbed two or three slide parts.”

That slide solo is one of your craziest.

“Definitely. I was just trying to capture a mood without worrying about technique.”

The beauty of your slide playing – and your blues playing in general – is you don’t mimic the originators. And you never really cleaned your blues up – you left it a little messy. Some white guys tend to be very anal.

“That’s right. That’s what I didn’t like about Mike Bloomfield – too perfect. I always just tried to do my thing. I could play traditional blues slide, but all the other guys reacted more enthusiastically to my untraditional slide playing. In fact, that’s what got me into the band. Jim always loved my slide playing – he wanted me to play it almost exclusively.”

Did Jim ever critique your playing?

“He would always tell me that I was the most underrated guitar player around. What’s funny is that the four of us hardly ever criticized the others’ playing – or even suggested anything. We worked so well together that we hardly ever had to talk about it. Everybody just played the right part in the right place at the right time.”

Cars Hiss By My Window is a rather unusual blues.

“Yeah. That was our Jimmy Reed piece. Jim was really getting into the blues at that time and he loved it when I would just play straight blues. He’d sit there and make up songs on the spot. He just wanted to play all night. It’s too bad because I really think that had we done another album it would have been a lot more straight blues stuff, which I always loved.”

How did Riders on the Storm develop?

“We were fooling around with Ghost Riders in the Sky one day and somehow it turned into Riders on the Storm. It just happened.”

Another change on L.A. Woman is the absence of reverb, particularly on Jim’s voice, which was so heavily reverbed on your first few albums.

“Well, Sunset Sound, where we recorded the first two albums, had one of the best echo chambers in the world. It was a live chamber, which they don’t make anymore. And it sounded so great that we used it a lot more than we might otherwise have. We piped everything through there.

“But L.A. Woman was recorded on an eight-track in our rehearsal space and Paul Rothchild was gone, which is one reason we had so much fun. The warden was gone.”

So, even after all your success, you still had that sort of relationship with the producer, where he was cracking the whip?

“Yeah, we just kind of took it for granted that he would produce and we would do things his way – you stick with success. And, finally, he was like a rat deserting a sinking ship. I think he figured it was time to bail.”

So there was a sense that the Doors were a sinking ship?

“Yeah, definitely. We couldn’t play anywhere, we were fucked because of the Miami incident. Morrison Hotel didn’t do that well, Jim looked bad and was getting fat… All things considered, I thought it was pretty cool that L.A. Woman did well.

“I think we came up with something so loose because there was no pressure. We figured we were already screwed, so we were having fun again. We were so far gone that it was like our first album.”

I thought he would never die. I thought he’d outlive everybody, like one of those Irish drunks who’d drink a fifth of whisky a day and live until they’re 80

Just weeks after the album entered the top 10, Jim was dead. Do you remember finding out?

“Yeah. I got a phone call and I didn’t believe it because we used to hear shit like that all the time – that Jim jumped off a cliff or something. So we sent our manager off to Paris, and he called and said it was true.”

People often talk about the inevitability of him dying young. Do you buy that?

“No! I thought he would never die. I thought he’d outlive everybody, like one of those Irish drunks who’d drink a fifth of whisky a day and live until they’re 80. He seemed invulnerable, the way he would do things and jump out of windows without getting hurt. I never saw those things, but I would hear about them the next day. For some reason, he was fairly well behaved around me. Somehow our relationship developed where he stayed fairly calm around me, thank God. [laughs]”

After Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin died, Jim supposedly told people that he would be the third to die at 27. Did you remember him saying such things?

“Yeah. He was definitely obsessed with death. He talked about it all the time.”

There’s always been talk that he’s not dead, and Ray has occasionally fueled that idea. Have you ever thought that?

“Yes and no. I’ve allowed myself to fantasize at times, but I’m sure that if he wasn’t dead he would have gotten hold of us by now. But then again, if there’s anybody who could pull off something like that, it was him. I still think about him quite a bit. I always have dreams that he’s alive, and we’re playing together again. Wishful thinking.”

This feature was originally published in Guitar World in 1994.

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).