I've spent 20 years as a touring guitarist. The live industry is broken – now it’s breaking musicians too. Here’s what needs to change

When an average gigging life includes permanent damage to financial, physical and mental wellbeing, it’s time to re-evaluate what the business is doing to the people who stand on stage

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

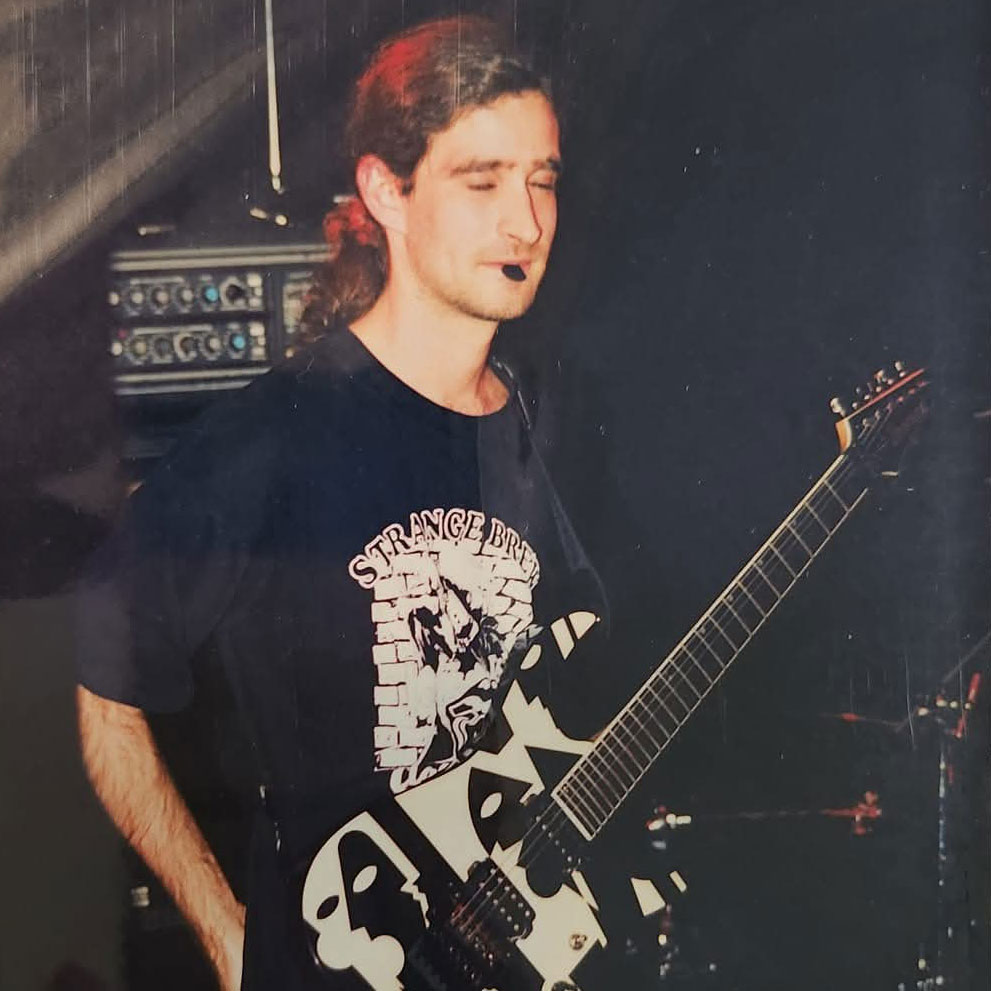

The last show I played looked great on Instagram. Stage lights, big tones, wall of cabs, arms in the air. What you couldn’t see in the photos was that I could barely stand upright.

During that gig my spine felt like someone had threaded barbed wire through it. My ears rang for three days afterwards. I went home to a house I could barely afford on disability support. And still spent the next morning re-stringing guitars for the next run.

That’s a part of live music most people never see.

I’ve spent roughly 20 years in the Australian extreme metal scene – clubs, festivals, support slots with bands like Napalm Death, Psycroptic and Gorguts – and I can tell you this: the industry isn’t just tough. It’s quietly chewing up the people who keep it alive.

We all know touring is hard and, for the vast majority of musicians, not lucrative. What we talk about far less is that it’s become normal to sacrifice your finances, physical health and sanity simply to keep stepping onstage.

Research from Help Musicians in the UK in 2016 found that 71 percent of musicians have experienced anxiety or panic attacks, with two-thirds reporting depression. In Australia, Support Act’s data shows that up to 66 percent of music workers experience high or very high psychological distress – that’s roughly four times the rate of the general population.

Those aren’t just numbers – they’re the people next to you at load-in.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The reality behind living the dream

From the outside, it looks like this: you get on a bill, you play big shows, you stand near famous logos on a poster. People assume you're being taken care of. From the inside, it's a different ledger.

For a period I was flying interstate every second weekend to gig with one band, while juggling another project at home. Back then, I was in two bands at once – rehearsals Monday for one, Tuesday for the other, both at the same place.

Both bands were playing interstate. There was always another set to nail, another tour to prep, another recording coming up – all while managing the aftermath of back surgery and navigating the disability support system.

I was covering my own costs: rehearsal room fees, flights, accommodation. Then one band told me I wouldn't be on their next album – they were using archival recordings from the ’90s instead. Covering everything myself was breaking me financially. I told both bands where to go.

Later I rejoined one of them, but only after setting conditions: they'd cover costs, I’d only pay for strings and fuel, and I wanted to be an actual member this time, not just a hired gun. The financial part worked. The membership part never did.

The singer had moved, turning rehearsals into a two-hour-plus trip each way. A car with no air-con and a driver’s window that only rolled down two inches, $14,000 ($20,000 AUD) worth of gear in the back, and a spine that already hated long drives. It was exhausting and it hurt; but it was still some of the best fun I've ever had.

My refusal to miss a show goes back to where I started. Since I picked up a guitar I’ve barely cancelled anything – maybe two or three rehearsals, and never a gig. As a kid I had to be out of the house by 5:30am on school days. I’d ride my pushbike across town to my best mate's place, and have a coffee and a chat with his mum until he got up for school.

Later his bedroom became our first venue: Iron Maiden and Skid Row every afternoon, treating those after-school jams like stadium shows. That's where the work ethic gets wired in: you turn up every time. no matter how you feel, no matter what it costs.

Bodies and minds as expendable gear

Musicians love to talk about tone and technique. We don't love to talk about what it costs our bodies to keep delivering shows.

Ask around any scene and you’ll hear the same stories: drummers with wrists held together by tape, vocalists bleeding through torn cords, guitarists who can’t feel their fretting hand properly. Tinnitus is so common it's almost a punchline. Back damage is “just part of the job.”

MusiCares in the US reports that 35 percent of musicians deal with chronic illness that affects their ability to work, while 78 percent can't pay their bills through music income alone. The unspoken rule is simple: if you stop, you disappear.

I've played sets where every note felt like someone jamming a hot knife into my lower spine. I’ve watched friends go onstage with fevers that would put most people in bed for a week, because there was no backup, no sick pay and a venue full of people who drove hours to be there.

We talk about “the grind” like it’s a badge of honour. It’s really slow self-harm with a laminate pass

Most bands I played with understood. They’d carry my amps, handle load-in and load-out, and make sure I wasn't lifting anything that would send me back to surgery. That solidarity is real, which is exactly why it cuts so deep when it vanishes.

We talk about “the grind” like it’s a badge of honour. It’s really slow self-harm with a laminate pass.

On hearing damage: I can’t use standard ear plugs because they cut the frequencies I need to hear my amp. However, mid to high ranges destroy the hair cells in your inner ear. Once they’re gone, that hearing’s gone permanently.

Being replaceable in the bands you bled for

The physical side is brutal, but the hardest hits I’ve taken have been to my sense of worth. I spent years building a tone I'm proud of, covering costs and giving everything to bands I believed in. Then you find out your work won't be on the next record. Or you set boundaries about what you can afford and suddenly you're not hearing from anyone anymore.

Every guitarist I know has that story. Parts re-recorded. Credits missing. Band photos updated without them. Most of us are treated like plug-in components: useful until we’re injured or inconvenient, then quietly written out.

What needs to change – and why I'd still do it all again

Underneath a lot of this is the same boring, brutal reality: the money doesn’t add up unless you’re in that tiny top tier. For years, every spare dollar I had went into keeping my part in the bands going – rehearsal rooms, flights, accommodation – and there was basically no life outside it.

If you run a venue or book acts, put posters up in your green rooms so musicians know help is available

We’re not going to fix the economics of live music overnight, but we can at least be honest that it’s a financial pressure cooker, acknowledge the support that exists, and push for better conditions on the ground.

I’m not talking about cartoon villains in suits. Most people I’ve worked with are just as broke and exhausted as I am. Promoters, venues, managers – everyone is scrambling. But there’s a difference between “this is tough” and “we accept players destroying themselves as the default.”

I don’t have a magic contract template. But there are things we can start doing that would make a real difference.

Firstly, and it’s been said before, but stop pretending exposure is payment – if a show is selling tickets and booze, the people making the noise deserve a guaranteed minimum.

Build health into the plan from the start – buffer days, decent ear protection, not punishing someone for needing a break. Put agreements in writing, even between friends, so you're not left off an album with nothing to point to. And normalise talking about burnout before someone disappears.

Organizations like Help Musicians (UK), Support Act (Australia) and MusiCares (US) are already doing critical work, offering counselling, financial support and health resources to music workers.

I didn’t know these organizations existed until I started writing this piece. If you run a venue or book acts, put posters up in your green rooms so musicians know help is available. A phone number on a wall might be the difference between someone reaching out and someone disappearing.

I still love this stupid, beautiful calling more than almost anything else in my life. Those long drives to rehearsal resulted in some of the best times I’ve ever had. I still chase that one note where the amp, the room and whatever’s left of my nervous system line up, and everything makes sense for a second.

We need a world where giving so much doesn’t quietly kill us

That’s why the industry has to change. Not because we’ll leave – but because we won’t – and we deserve better than being ground down until we physically can’t continue.

If you’re a player, I hope this makes you feel less alone. If you're a fan, I hope it makes you look twice at the guitarist loading out alone at 1am, and take a moment to remember there’s a whole life behind that tone. And if you run a venue or book the acts, I hope it makes you think about what “exposure” costs the people on stage.

We’ll keep giving you our best. We just need a world where giving that much doesn’t quietly kill us.

- If you're struggling with any of the issues raised in this piece, reach out – MusiCares (US): 1-800-687-4227.; Help Musicians (UK): 0800 030 6200; Support Act (Australia): 1800 959 500.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.